Полная версия

A Time of Exile

Voyager

KATHARINE KERR

A Time of Exile

A Novel of the Westlands

COPYRIGHT

Voyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by GraftonBooks 1991

Copyright © Katharine Kerr 1991

Katharine Kerr asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan–American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780586207888

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2014 ISBN: 9780007400980

Version: 2014–08–18

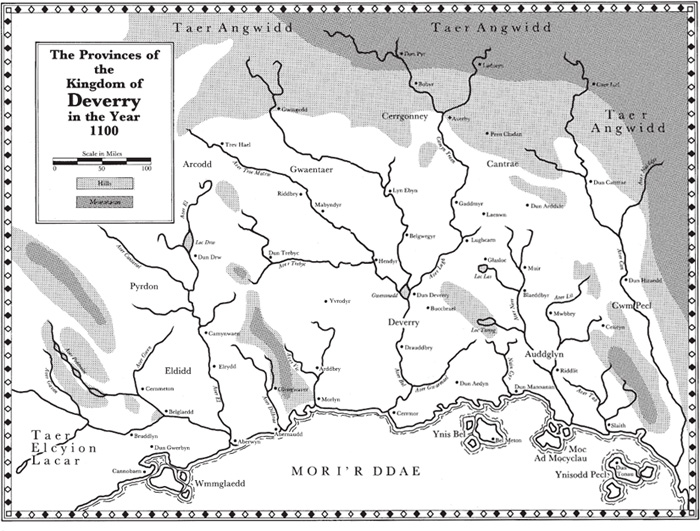

MAP

DEDICATION

tibi, Dea, nominis pro gloria tuae

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Map

Dedication

Prologue: The Eldidd Border 1096

Part One: Deverry and Eldidd 718

One

Two

Part Two: The Elven Border 719–915

Part Three: Eldidd 918

One

Two

Three

Epilogue: The Elven Border Summer, 1096

Keep Reading

Appendices

Glossary

About the Author

Other Books By

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

The Eldidd Border 1096

‘As thrifty as a dwarf’ is a common catch-phrase, and one that the Mountain People take for a compliment. Although they see no reason to waste anything, whether it’s a scrap of cloth or the heel of a loaf, they keep a particularly good watch over their gemstones and metals, though they never tell anyone outside their kin and clan just how they do it. Otho, the silver daggers’ smith down in Dun Mannannan, was no different from any other dwarven craftsman, unless he was perhaps more cautious than most. His usual customer was some hotheaded young lad who’d dishonoured himself badly enough to be forced to join the silver daggers, and you have to admit that a wandering swordsman who fights only for coin, not honour, isn’t the sort you can truly trust with either dwarven silver or magical secrets.

During his long years among humans in the kingdom of Deverry, Otho taught a few other smiths how to smelt the rare alloy for the daggers, an extremely complicated process with a number of peculiar steps, such as words to be chanted and hand gestures to be made just so. Otho would always refuse to answer questions, saying only that if his students wanted the formula to come out right they could follow his orders, and if they didn’t, they could get out of his forge right then and spare everyone trouble. All the apprentices shut their mouths and stayed; they were bright enough to realize that they were being taught magic of some sort, even if they weren’t being told what the spells accomplished. Once they opened shops of their own, they went on repeating Otho’s procedures in the exact way they’d been taught, so that every dagger made of dwarven silver in Deverry carried two kinds of dweomer.

One spell Otho would acknowledge, especially to someone that he liked and trusted; the other he would have hid from his own brother. The first produced in the metal itself an antipathy to the auric vibrations of the elven race, so that the dagger glowed brightly the moment an elf came within a few feet of it. The other, the secret spell, was its necessary opposite, producing an affinity, in this case to the dagger’s true owner, so that if lost or stolen, sooner or later the magical currents of the universe would float that dagger home. The thing was, by ‘true owner’ Otho meant himself, which meant that any lost dagger would eventually come home to him, no matter who had actually made it or how much its interim owner had paid for it. Otho justified all of this by thinking of the purchase price as mere rent, a trifling detail that he never mentioned to his customers.

Once and only once had Otho produced an exception, and that was by accident. Round about 1044, he made a dagger for Cullyn of Cerrmor, one of the few human beings he truly admired. In the course of things, that blade passed to Rhodry Maelwaedd, a young lord who was forced by political exile to join the silver daggers. As soon as Rhodry laid his hand on the dagger, it was obvious that his blood was a little rarer than merely noble – the blade blazed up and accused him of being half an elf at least. Grudgingly, and only as a favour for Cullyn of Cerrmor’s daughter, Otho took off the denouncing spell. What Otho didn’t realize, since his dweomer was a thing of rote memory rather than real understanding, was that he’d weakened the complementary magic as well. The dagger now saw Rhodry, not the dwarf, as its one true owner.

A silver dagger’s life is never easy, and Rhodry’s time on the long road was worse than most, and by one thing and another he managed to lose the blade good and proper, far away in the Bardekian archipelago across the Southern Sea, round about the year 1064. At the same time as Rhodry was killing the man who’d stolen it. the dagger itself fetched up in the marketplace of a little mountain town called Ganjalo, where it stayed for several years, stubbornly unsold. The merchant couldn’t understand – here was this beautiful and exotic item, reasonably priced, that no one ever seemed to want to buy. Finally it did catch the eye of an itinerant tinker, who knew of a rich man who collected unusual knives of all sorts. Since this rich man lived in a sea-port, the dagger allowed itself to be installed in the collection. Again, some years passed, until the collector died and his sons divided up the various blades. The youngest, who happened to be a ship’s captain, felt drawn to the dagger for some irrational reason and traded another brother an entire set of pearl-handled fish knives for it. The next time this captain went to sea, the dagger went with him.

But not to Deverry. The captain sailed back and forth from Bardek proper to the off-lying islands of Orystinna, a lucrative run, and he saw no reason to consider making the dangerous crossing to the distant barbarian kingdoms. After some years of this futile east–west travel, the dagger changed owners. While gambling, the captain had an inexplicable run of bad luck and ended up handing the dagger over to a friend to pay off his debt. The friend took it to a northern sea-port and on a sudden whim sold it to another marketplace jeweller who bought it on the same kind of impulse. There it lay again, until a young merchant passed by and happened to linger for a moment to look over the jeweller’s stock. Since this Londalo traded with Deverry on a regular basis, he was always in need of little gifts to smooth his way with customs officials and minor lords. The dagger had a barbarian look, and he bought it to take along on his next trading run.

Of course, poor Londalo didn’t realize that, in Deverry, offering a silver dagger as a gift was a horrible insult. He found out quick enough in the Eldidd town of Abernaudd, where his ill-considered gesture cost him a trading pact. As he bemoaned his bad luck in a tavern, a kindly stranger explained the problem, and Londalo nearly threw the dagger onto the nearest dung-heap then and there, which was more or less what the dagger had in mind. Yet, because he also knew a lesson when he saw one, he ended up keeping it as a reminder to never take other people’s customs for granted again. If silver could have feelings, the dagger would have been livid with rage. Back and forth it went between Bardek and the Deverry coast for some years more, while a richer, older Londalo became a respected and important member of his merchant guild, until finally, in the spring of the year 1096, he and the dagger turned up in Aberwyn, where Rhodry Maelwaedd now ruled as gwerbret. The magical currents around the dagger thickened, swirled, and grew so strong that Londalo actually felt them, as a prick of something much like anxiety.

On the morning that he was due to visit the gwerbret, Londalo stood in his chamber in the best inn Aberwyn had to offer and irritably applied his clan markings. Normally a trained slave would have painted on the pale blue stripes and red diamonds that marked him as a member of House Ondono, but it was very unwise for a thrifty man to bring his slaves when he visited the kingdom of Deverry. Surrounded by barbarians with a peculiar idea of property rights, slaves were known to take their chance at freedom and disappear. When they did, the barbarian authorities became uncooperative at best and hostile at worst. Londalo held his hand mirror at various angles to examine the paint on his pale brown skin and finally decided that his amateur job would have to do. After all, the barbarians, even an important one like the lord he was about to visit, knew nothing of the niceties of the art. Yet the anxiety remained. Something was wrong; he could just plain feel it.

There was a knock at the door, and Harmon, his young assistant, entered with a respectful bob of his head.

‘Are you ready to leave, sir?’

‘Yes. I see you have the proposed trade agreements with you. Good, good.’

With a brief smile Harmon patted the heavy leather roll of a document case that he carried tucked under one arm.

As they walked through the streets of Aberwyn, Londalo noticed his young partner looking this way and that in distaste; occasionally he lifted a perfumed handkerchief to his nose as they passed a particularly ripe dung-heap. There was no doubt that visiting Deverry was hard on a civilized man, Londalo reflected. The city seemed to have been thrown down around the harbour rather than built according to a plan. All the buildings were round and shaggy with thatch, instead of square and nicely shingled; the streets meandered randomly through and around them like the patterns of spirals and interlace the barbarians favoured as a decorative style. Everywhere was confusion: barking dogs, running children, men on horseback trotting through dangerously fast, rumbling wagons, and even the occasional staggering drunk.

‘Sir,’ Harmon said at last, ‘is this really the most important city in Eldidd?’

‘I’m afraid so. Now remember, my young friend, this man we’re going to visit will look like a crude barbarian to you, but he has the power to put us both to death if we insult him. The laws are very different here. Every ruler is judge and advocate both, as long as he’s in his own lands. And a gwerbret, like our lord here in Aberwyn, is a ruler far more powerful than one of our archons.’

In approximately the centre of town lay the palace complex, or dun as the barbarians called it, of the gwerbret. The barbarians all talked about how splendid it was, with its many-towered fortress inside the high stone walls, but the Bardekians found the stone work crude and the effect completely spoiled by the clutter of huts and sheds and pig-sties and stables all around it. As they made their way through the bustle of servants, Londalo suddenly realized that he was wearing the silver dagger on his tunic’s leather belt.

‘By the Star Goddesses! I must be growing old! I don’t even remember picking this thing up from the table.’

‘I don’t suppose it’ll matter, sir. All the men around here are absolutely bristling with knives.’

Although Londalo had never met this particular ruler before, he’d heard that Rhodry Maelwaedd, Gwerbret Aberwyn, was an honest, fair-minded man, somewhat more civilized than most of his kind. Londalo was pleased to notice that the courtyards were reasonably clean, the servants wore decent clothing, and the corpses of hanged criminals were nowhere in sight. At the door of the tallest tower, the broch proper, the aged chamberlain was waiting to greet them. In a hurried whisper Londalo reminded Harmon that a gwerbret’s servitors were all noble-born.

‘So mind your manners. No giving orders, and always say thank you when they do something for you.’

The chamberlain ushered them into a vast round room, carpeted with braided rushes and set about with long wooden tables, where at least a hundred men, all of them armed with knife and sword both, were drinking ale and nibbling on chunks of bread, while servant girls wandered around, gossiping or trading smart remarks with the men more than working. Near a carved sandstone hearth to one side, one finer table stood alone, made of ebony and polished to a shine, the gwerbret’s place of honour. Londalo was well pleased when the chamberlain seated them there and had a boy bring their ale in actual glass stoups. Londalo was also pleased to see that the tapestry he’d sent ahead as a gift was hanging on the wall near the enormous fireplace. As he absently fingered the hilt of the silver dagger, he realized that his strange anxiety had left him. Harmon, however, was nervous, glancing continually at the mob of armed men across the hall.

‘Now, now,’ Londalo whispered. ‘The rulers here do keep their men in hand, and besides, everyone honours a guest. No one’s going to kill you on the spot.’

Harmon forced out a smile, had a sip of ale, and nearly choked on the bitter, stinking stuff. Like the true merchant he was, however, he covered over his distaste with a cough and forced himself to try again. In a few minutes, two young men strode into the hall. Since their baggy trousers were woven from one of the garish plaids that marked a Deverry noble, and since the entire warband rose to bow to them, Londalo assumed that they were a pair of the gwerbret’s sons. They looked much alike, with wavy raven-dark hair and cornflower-blue eyes. By barbarian standards they were both handsome men, Londalo supposed, but he was worried about more than their appearance.

‘By the Great Wave-father himself! I was told that there was only one son visiting here! We’ll have to do something about getting a gift for the other, no matter what the cost.’

The chamberlain bustled over, motioning for them to rise, so they’d be ready to kneel at the proper moment. Having to kneel to the so-called noble-born vexed Londalo, who was used to voting his rulers into office and voting them out again, too, if they didn’t measure up to his standards. As one of the young men strolled over, the chamberlain cleared his throat.

‘Rhodry, Gwerbret Aberwyn, the Maelwaedd, and his son.’

In his confusion, Londalo almost forgot to kneel. Why, this lord could be no more than twenty-five at most! Mentally he cursed the merchant guild for giving him such faulty information for this important mission.

‘We are honoured to be in your presence, great lord, but you must forgive our intrusion in what must be a time of mourning.’

‘Mourning?’ The gwerbret frowned, puzzled.

‘Well, when we set sail for your most esteemed country, Your Grace, your father was still alive, or so I was told, the elder Rhodry of Aberwyn.’

The gwerbret burst out laughing, waving for them to rise and take their seats again.

‘I take it you’ve never seen me before, good merchant. I’ve ruled here for thirty years, and I’m four and fifty years old. I’m not having a jest on you, either.’ Absently, he looked away, and suddenly his eyes turned dark with a peculiar sadness. ‘Oh, no jest at all.’

Londalo forgot his protocol enough to stare. Not a trace of grey in the gwerbret’s hair, not one true line in his face – how could he be a man of fifty-four, old back home, ancient indeed for a barbarian warrior? Then the gwerbret turned back to him with a sunny smile.

‘But that’s of no consequence. What brings you to me, good sir?’

Londalo cleared his throat to prepare for the important matter of trading Eldidd grain for Bardekian luxuries. Just as he was about to speak, Rhodry leaned forward to stare.

‘By the gods, is that a silver dagger you’re carrying? It looks like the usual knobbed pommel.’

‘Well, it is, Your Grace.’ Mentally Londalo cursed himself all over again for bringing the wretched thing along. ‘I bought it in the islands many years ago, you see, and I keep it with me because … well, it’s rather a long story …’

‘In the islands? May I see it, good merchant, if it’s not too much trouble?’

‘Why, no trouble at all, Your Grace.’

Rhodry took it, stared for a long moment at the falcon device engraved on the blade, and burst out laughing.

‘Do you realize that this used to be mine? Years and years ago? It was stolen from me when I was in the islands.’

‘What? Really? Why, then, Your Grace absolutely must have it back! I insist, truly, I do.’

Later that afternoon, once the treaty was signed and merchant on his way, the great hall of Aberwyn fell quiet as the warband went off to exercise their horses. Although normally Rhodry would have gone with them, he lingered at the table of honour and considered the odd twist of luck, the strange coincidence, as he thought of it, that had brought his silver dagger home to him. A few serving lasses wandered around, wiping down tables with rags; a few stablehands sat near the open door and diced for coppers; a few dogs lay in the straw on the floor and snored. In a while, his eldest son came down to join him. It was hard to believe that the lad was fully grown, with two sons of his own now and the Dun Gwerbyn demesne in his hands. Rhodry could remember how happy he’d been when his first heir was born, how much he’d loved the little lad, and how much Cullyn had loved him. It hurt, now, thinking that his first-born was beginning to hate him, and all because his father refused to age and die. Not that Cullyn ever said a word, mind; it was just that a coolness was growing between them, and every now and then, Rhodry would catch him staring at the various symbols of the gwerbretal rank, the dragon banner, the ceremonial sword of justice, with a wondering sort of greed. Finally, Rhodry could stand the silence no longer.

‘Things are quiet in the tierynrhyn, then?’

‘They are, father. That’s why I thought I’d ride your way for a visit.’

Rhodry smiled and wondered if he’d come in hopes of finding him ill. He was an ambitious man, Cullyn was, because Rhodry had raised him to be so, had trained him from the time he could talk to rule the vast gwerbretrhyn of Aberwyn and to use well the riches that the growing trade with Bardek brought it. He himself had inherited the rhan half by accident, and he could remember all too well his panicked feeling of drowning in details during the first year of his rule to allow his son to go uneducated.

‘That’s an odd thing, Da, that dagger coming home.’

‘It was, truly.’ Rhodry picked it up off the table and handed it to him. ‘See the falcon on the blade? That’s the device of the man you were named for.’

‘That’s right – he told me the story. Of how he was a silver dagger once, I mean. Ye gods, I still miss Cullyn of Cerrmor, and here he’s been dead many a long year now.’

‘I miss him too, truly. You know, I think I’ll carry this dagger again, in his memory, like.’

‘Oh, here, Da, you can’t do that! It’s a shameful thing!’

‘Indeed? And who’s going to dare mock me for it?’

Cullyn looked away in an unpleasant silence, as if any possible mention of social position or standing could spoil the most innocent pleasure. With a sigh, he handed the dagger back and picked up his tankard again.

‘We could have a game of Carnoic,’ Rhodry said.

‘We could, at that.’ When Cullyn smiled at him, all his old affection shone in his dark blue eyes. ‘It’s too muggy to go out hunting this afternoon.’

They were well into their third game when Rhodry’s wife, the Lady Aedda, came down to join them at the honour table. She sat down quietly, even timidly, with a slight smile for her son. At forty-seven she had grown quite stout, and there were streaks of grey in her chestnut hair and deep lines round her mouth. Although theirs was a politically arranged marriage, and in its first years a miserable one, over time she and Rhodry had worked out a certain accommodation to each other. He felt a certain fondness for her, a gratitude that she had given him four strong heirs for Aberwyn.

‘If my lady wishes,’ Rhodry said, ‘we can end this game.’

‘No need, my lord. I can watch.’

And yet, by a common, unspoken consent they brought the game to a close and put the pieces away. Aedda had asked for so little from both of them over the years that they were inclined to give her what small concessions they could. As the afternoon wore on in small talk about the doings of the various vassals in the demesne, Rhodry drank more and more and said less and less. The heat, the long silences, the predictability of his wife’s little remarks all weighed him down until at last he got up and strode out of the hall. No one dared question him or follow.

His private chamber was on the third floor of a half-broch, a richly furnished room with Bardek carpets on the floor and glass in the windows, cushioned chairs at the hearth and a display of five beautifully worked swords on one wall. Rhodry threw open a window and leaned on the sill to look down on the ward and the garden, where the dragon of Aberwyn sported in a marble fountain far below. One old manservant ambled across the lawn on some slow errand; nothing else moved. For a moment Rhodry felt as if he couldn’t breathe. He tossed his head with an oath that was half a keening and turned away.

For over thirty years he had held power, and for most of those years he loved it all: the symbols and pageantry of his rank, the tangible power that he wielded in his court of justice and on the battlefield, the subtle but even greater power he exercised in the intrigues of the High King’s court. As he looked back, he could remember exactly when that love turned sour. He was at the royal palace in Dun Deverry, and as he entered the great hall, the chamberlain of course announced him. At the words ‘Rhodry, Gwerbret Aberwyn’, every other noble-born man there turned to look at him, some in envy of one of the king’s favourites, some in subtle calculation of what his presence would mean to their own schemes, others with simple interest in the sight of so powerful a man. All he felt in return was irritation, that they should gawk at him like a two-headed calf in the market fair. And from that day, some two years earlier, Rhodry had slowly come to wonder when he would die and be rid of everything he once had loved, free and shot of it at last.