Полная версия

Man of Honour

IAIN GALE

Man of Honour

Jack Steel and the Blenheim Campaign,

July to August 1704

For Sarah

Contents

Title Page Dedication Prologue Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Epilogue Historical Note Rules Of War Chapter One About the Author Also By Iain Gale Copyright About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

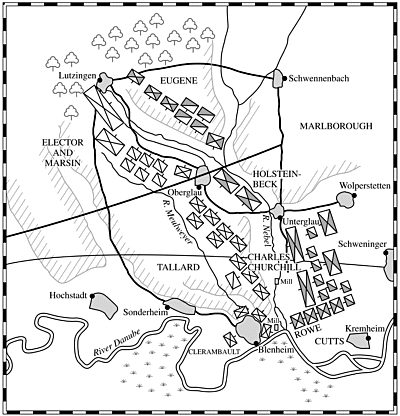

Upper Bavaria, July 1704

They had come here by stealth to carry the war deep into the south. An army of many nations: English and Scots, Hanoverians and Prussians, Hessians, Danes and Dutch. They had but one purpose: the defeat of France and her ally, Bavaria. The French King, Louis XIV, they knew to be a power-mad maniac, styling himself the Sun King. It was clear that he would not be content until he possessed all Europe, from Spain to Poland. And so it was, on this sultry day in early July, as afternoon drifted into evening, that fate brought these many thousands of men to Donauwö rth, a little Bavarian town with its ancient high walls and ramparts.

Above it, at the top of a steep slope, stood a fort whose hill, inspired by its distinctive shape, the local people had long ago christened ‘Schellenberg’ – The Hill of the Bell. It was abundantly and worryingly clear to all the soldiers who now stood in its shadow, that before any decisive victory could be won, before they could bring the French to battle, drive them back to Paris and remove forever the Sun King’s threat, that this hill and its little fort would have to be taken.

ONE

The tall young officer stood a few yards out in front of the company of redcoats and stared up at the fort that towered above them on the hill. For two hours now he had been awaiting the order to advance and with every passing moment the enemy position looked more forbidding. Like almost every man in the army, he had the greatest admiration and respect for his Commander-in-Chief. But at this precise moment he had begun to wonder whether, truly, this entire enterprise might not be doomed to failure. He tried to banish the thought. To maintain some degree of sang-froid before his men. But as he did so, the first cannonball fell in front of the three ranks of red-coated infantry, bounced up from the springy turf with grisly precision, and carried away four of them in a welter of blood and brains.

‘Feeling the heat, Mister Steel?’

The Lieutenant looked up. Silhouetted against the sun a tall figure in a full-bottomed wig peered down at him from horseback.

‘A trifle, Sir James.’

‘A trifle, eh? I’d have thought that you’d have been used to it after, how many years a soldier?’

‘Nigh on a dozen, Colonel.’

‘But of course. How could I forget? You earned your spurs in the Northern wars, did you not? Fighting the Rooshians. A little colder there I dare say.’

‘A little, Colonel.’

‘Can’t imagine why you should have wanted to go there at all. Narva, Riga? What sort of battles were those, eh?’

The question was not intended to have a reply.

‘Well, Steel, what think you of our chances today? Shall we do it?’

‘I believe that we can, Sir. Though it will not be easily done.’

‘No, indeed. Yet we must take this town. It is the key to the Danube and the gateway to Bavaria. And to do that we needs must take the fort. And we must do it by frontal assault. There is no other way. You would say, Steel, that the rules of war dictate we must do it by siege. And you would be right. But we have no siege guns and thus our Commander-in-Chief, His Grace the Duke of Marlborough, dictates that this is the way it shall be done. And so it shall. We will attack up that hill into the face of their guns.’

He paused and shook his head. ‘Our casualties will be heavy. God knows, Steel, this is not the proper way to win a battle. It will not be like any of the battles you saw with the Swedes, I’ll warrant. Eh? Rooshians and Swedes, Steel. Indeed I can’t fathom what you saw in it. No Rooshians today, Steel. Only the French and their Bavarian friends to beat. Still. Hot work, eh? Good day to you.’

Colonel Sir James Farquharson laughed, touched his hat to the young Lieutenant and trotted away down the line of the battalion, his voice echoing above the rising cannonfire as he shouted greetings to the other company commanders of the advance storming party:

‘Good afternoon, Charles. Good day to you, Henry. We dine in Donauwörth this evening, I believe.’

Steel shook his head and smiled. Yes, he thought. He could see why Sir James would not understand the reasons why he should have wished to fight with the Swedes. That it would never occur to his Colonel to take yourself off to find a war. Soldiering for Sir James Farquharson was a gentlemanly affair. A thing of parades and banners. But if there was one thing that Jack Steel had learnt in the last twelve years it was that there was nothing gentlemanly about war. Nothing whatsoever.

He turned his head towards his men. Saw the lines being redressed by the sergeants and the corporals, the bloody gaps filled up from the rear with fresh troops. The dismembered bodies being dragged away.

‘The Colonel seems happy, Sir. Do you suppose he thinks we’re going to win?’

The surprisingly mellifluous voice belonged to Steel’s Sergeant, Jacob Slaughter. Six foot two of Geordie and the only man in the company broader and taller than Steel himself. Gap-toothed, loose-limbed Sergeant Slaughter, who had run away to join the colours to avoid being sent to work in the new coal mines of County Durham. Towering Sergeant Slaughter who was so terrified of small spaces, who couldn’t abide the dark and was unutterably clumsy in all manner of things. But who, on the field of battle was a man transformed, as skilled and calculating a killer as Steel had ever encountered. A man next to whom, more than any other, you would want to stand when all around you the world had dissolved in a boiling surf of blood and death. Steel greeted him with a smile.

‘D’you need to ask, Jacob? Sir James doesn’t think we’ll win. He knows it. Our Colonel raised this regiment, his regiment with his name, from his own pocket. He wants us to be the finest in the British army. It’s not just our lives that’ll be at stake up there. It’s his money and his pride. He needs a few battle honours. And it’s up to us to give them to him.’

‘D’you think we’ll be going in soon then, Sir? I’m startin’ to get a dreadful thirst.’

‘By God, Jacob. That thirst of yours is no respecter of time and place. Here we stand, about to launch possibly the most desperate feat of arms to which you or I have ever been party – and quite probably our last – and you tell me you want a drink. I tell you, Sarn’t, there’ll be drink a plenty if we take this damned town. Don’t you worry. I’ll personally find you a cask of the finest Moselle.’

‘You’re as fine a gentleman as I’ve ever known, Mister Steel, and I’ll take you at your word. But if you really mean it, Sir, I’d sooner have a barrel of German ale than any bloody wine – if it’s all the same with you.’

He paused. His attention drawn by sudden movement towards the right of the line.

‘Aye aye. Looks like we might be on the move.’

Following his Sergeant’s gaze, Steel saw a galloper. A young Cornet of Cavalry mounted on a handsome black mare, racing at speed down the lines. Here then, at last, was the order. And not before time. They had marched, halted and been ordered at stand-to since three o’clock that morning. Now it was nearing six in the evening. Surely now they must go. The men were restless. They would not stand for much more delay, or they would lose their nerve. Steel looked about him. Back down the slope he was able to see the massed battalions and squadrons of the main army, including the other ten companies of his own regiment.

Guidons and colours flew from their spear-topped poles, high above serried ranks of red, blue, grey, brown, and green as the allies assembled their might to follow into the gap that it was confidently presumed would be made by the storming party.

It was more evident than ever, he thought, what a rag-bag army this was. English, Scots, Irish, and an unlikely union of Dutchmen, Hessians, Prussians and Danes. Walk through their camp and you would find men communicating with each other by sign language, or attempting some laughable patois. Steel, ironically, had always found that the easiest language to use – that most understood by his allied counterparts – was the French of their enemies. He wondered how the allied army would hold together under fire. Oh, he did not doubt the Duke’s capabilities with their own contingent. But how would so many foreigners suffer being commanded by an Englishman? Nevertheless, you could not help but admire the sight.

‘A fine view, Jack, is it not?’

Steel’s fellow officer, Lieutenant Henry Hansam, was standing beside him, holding open a small silver snuff box.

‘Care for a pinch?’

Steel waved him away. Hansam took a good pinch and inhaled deeply before continuing:

‘Although little good it does us. We are quite alone up here. They expect a miracle of us, Jack. Nothing less than a miracle.’

He let out a loud sneeze, withdrew a silk handkerchief from his sleeve and wiped his nose. Steel spoke.

‘Well, Henry. Can we manage it? Shall we give them their miracle?’

‘We are the choice troops, you know. If we cannot take this position then most certainly it cannot be achieved. We are the chosen few. Forty-five times one hundred and thirty men, plucked from each English and Scots battalion on this field. The Duke himself has had a hand in our choosing. Naturally Sir James sends only his Grenadiers. And why not? It is the very purpose for which the Grenadiers were created. We are the “storm” troops. We have the height, the agility, the strength. And, by God Jack, you know we have the heart to do it.’

Steel cast a sideways look at their company. They were giants among men. Not one among them under five foot ten. They had been chosen, too, for their experience and skill with arms; their ability to move fast and to operate on their own initiative.

They were the finest infantry in Queen Anne’s army and soon he would lead them forward, up the hill and, God willing, into the fort. To death or glory and the promise of a handsome bounty. Looking up again at the dark mass of the fort, Steel could not suppress a chill shudder of apprehension. He looked away and pretended to straighten his sash. Hansam sneezed again through his snuff, wiped his nose with the now discoloured square of silk.

Steel looked at his friend, who, along with him, bore the title unique to the Grenadiers of ‘Second Company Lieutenant’. With Colonel Farquharson keen to draw for himself the additional pay that came with the nominal command of their company, Hansam and Steel between them found that they now commanded the Grenadiers in the field yet without the status or pay of a captain. Nor had they any junior officers.

Their last Ensign, a weak-livered boy of fifteen, had left them at Coblenz – invalided out with chronic dysentery. As yet they had found no replacement. Steel spoke, quietly:

‘Of course, there is the bounty money.’

Hansam raised his eyebrows.

‘Of course, Jack. We cannot delude ourselves that the men will do it entirely for the love of Queen and country. Nor even, dare I say it, for love of the Duke. Keep them happy and they’ll fight. Oh yes. They’ll fight. For the bounty.’

‘I was talking, Henry, about our own share.’

‘Oh.’

Hansam paused, then grinned.

‘Naturally, my dear fellow. Of course. We may profit too. Point of fact, I never did understand quite how someone as financially limited and indeed as frugal as yourself, had ever come to have started off in the Foot Guards. Although perhaps now I do see your reasons for transferring from that illustrious regiment to join our happy band.’

Steel nodded his head. Hansam spoke again, smiling:

‘Perhaps, Jack … if we should survive, I might persuade you to accompany me to a proper tailor, in London. I mean take a look at yourself, Jack. Why, your hat alone …’

Steel looked down at the hat which he held in his hand. Unlike some Grenadier officers, he did not choose to wear the mitre cap, but preferred his battered, gold-laced black tricorne. In fact he habitually fought bareheaded. And anyway, at six foot one, as the second tallest man in the company, he knew that a Grenadier’s mitre cap would have made him look less frightening than absurd. Besides, the most precious lesson he had got from twelve years of soldiering, nine of them with the colours, was that to survive as an officer you should not offer the enemy too obvious a target and yet at the same time must be sufficiently distinctive to be instantly recognisable to your own men.

‘Well, Henry. It does let the men know where I am.’

Hansam laughed. For both officers knew that, with or without his hat, his men could hardly mistake Steel. Apart from his height, there was his hair, which rather than cutting short and covering with a full wig, as was the fashion, he preferred to wear long and tied back in a bow with a piece of black ribbon: another practical trick learnt on the field of battle.

‘I say.’

Hansam was pointing along the line.

‘We appear to be under orders.’

Steel could see that the galloper had reached the senior commanders of the storming party now. They had dismounted, as was common practice, to lead the attack on foot. He could make out Major-General Henry Withers and Brigadier-General James Ferguson, commanders respectively of the English and Scots troops of the assault force. Beside them stood the determined figure of Johan Goors, the distinguished, middle-aged Dutch officer of engineers, well known for his opposition to Baden, to whom Marlborough had entrusted overall command of the assault.

The officers had gathered near, although not too close, to the ‘forlorn hope’, a band of some eighty men – volunteers all, drawn from Steel’s old regiment, the First Foot Guards – whose unhappy task, as their name suggested, was to go first into the defences and discover by their own sacrifice where the enemy might be strongest. To put it bluntly, they would draw the enemy’s fire on to themselves. Most of them would die. But for those who survived there would be the greatest rewards and celebrity. Immortality even. At its head Steel saw the unmistakeable tall and handsome Lord John Mordaunt. The two had served together for a time and Steel had been somewhat surprised last year when Mordaunt had been refused the hand of Marlborough’s daughter. Perhaps the honour of leading the ‘hope’ now was some self-inflicted penance for that amorous failure. Or Mordaunt’s last chance possibly to win the admiration of the man who might have been his father-in-law. From the right, a squadron of English dragoons now approached their line. Steel noticed that each trooper carried in front of him across his saddle two thick bundles of what looked like sticks, tied together with rope. The cavalry broke into open order and began to ride between each rank of the Grenadiers, handing out the bundles of fascines, one to each man. To the officers too. Steel took his own realizing how cumbersome it was. These though were the vital tools that they were to use to cross the great defensive ditch that they had discovered lay in their way at the top of the hill, a short distance in front of the breastworks.

A thunderous roar made Steel turn momentarily and up on the gentle hill behind them he saw flame spout from the mouths of ten cannon. The sum total of the allied artillery had been stationed there, close to a small village set afire by the French in an attempt to impede their progress. Ten guns. That was all that they had to soften up the defences that lay above them. The balls flew over their heads and disappeared high up on the enemy position. Well, it appeared that at least someone in the high command was trying to prepare the way for their assault.

At the foot of the Schellenberg, all now safely across the stream, stood the formed ranks of the main army. English, Scots, Dutchmen and the men from Hesse and Prussia who had joined them at Coblenz. Steel watched as the evening sun glanced off the green slopes of the hill and the brown line of the basketwork gabions. Soon, he knew, this pretty field would be transformed into a bloody killing ground.

Instinctively, with the eye of the veteran, he began to calculate how far they would have to travel to make it to the defences. Four hundred yards perhaps. Hansam smiled at him.

‘Well, that’s it then. I suppose that we had better take our stations. No point in giving their gunners too obvious a target. Until we meet again, Jack, at the top of the hill.’

‘At the top of the hill, Henry.’

Almost before he could sense the hollow ring of his words, he was suddenly aware of the reassuring presence of Sergeant Slaughter at his side.

‘Ready, Sir? I think we’re really off now.’

Steel felt the old emptiness in his stomach that always marked the approach of battle.

He knew that the only way to appear in control was to force your way through it.

‘Very good Sarn’t. Have the men make ready.’

Slaughter turned to the ranks.

‘All right. Let’s have you. Look to it now. Smarten up. Dress your ranks.’

They were standing six deep now, rather than in the customary four ranks. Six ranks to push with sheer weight of numbers as deep as possible into the fortifications and through the men beyond. But six ranks that would give equally such easy sport to the enemy guns whose cannonballs, falling just short of the front man, would bounce up and through him before continuing to take down another five, ten, twenty in his wake. Slaughter barked the command:

‘Grenadiers. Fix …’ he drew breath.

With one motion the Grenadiers drew the newfangled blades from their sheaths fumbling with the unfamiliar fastenings. Slaughter finished:

‘… bayonets.’

With a rattle of metal against metal the company fixed the clumsy sockets on to the barrels of their fusils. A distant voice, the confident growl of General Goors, speaking in a slow and particular tone and loud to the point of hoarseness, rang out across the field.

‘The storming party will advance.’

The pause that followed, as Goors turned to his front seemed an eternity. And then his single word of command.

‘Advance.’

Along the line, the order was taken up by a hundred sergeants and lieutenants. Behind each regimental contingent two fifers began a tune that on the fifth bar, with a fast, rising roll, was taken up by the drummer boys. The familiar rattle and paradiddle of ‘the Grenadiers’ March’.

Then, with a great cheer, the line began to walk forward. Steel measured his pace. Not with the precision of the Prussians or the Dutch, who were always directed by their blessed manual of rules to walk into battle: ‘as slow as foot could fall’. But rather with the singular, slow step of the British infantry. A gentle step, as their own manual directed, designed to ensure that the men would not be ‘out of breath when they came to engage’. It was certainly an easy pace, he thought. But deadly. And under cannonfire quite the last way in which you would want to conduct yourself.

Walking forward now, as the enemy shot began to fly in earnest towards their lines, Steel felt his feet begin to sink into the soft ground. Weighed down by their bundles of faggots, the men soon found they could not gather pace. Four hundred yards, thought Steel. Good God. It seemed more like a mile now, stretching out before him up the hill. No hill now, but a mountain, from the top of which he saw guns belch more gouts of flame as the French artillery opened up with its full force. Ten, twenty roundshot at a time came leaping at them down the slope, finding a home in the ranks behind him. Steel heard the cries to his rear as his own men were blown to oblivion. He repeated a litany in his head: ‘Face the front. Keep looking to the front. Don’t be distracted. Don’t, for pity’s sake, look back.’

He heard Slaughter close behind him, through the cacophany of shot, bark another, familiar command: ‘Dress your ranks. Keep them steady. Corporal Jenkins. Your section. Keep it steady now, mind.’

Keep steady. It was madness in this hail of roundshot and grenades. But there was no other way. A cannonball flew past his left elbow. Steel felt the shockwave. Another roundshot came hurtling towards him and passed horribly close, before taking off the head of one of the second-rank men and continuing down the hill. To his left he could see Henry Hansam advancing at a similar walking pace. The drums were driving them forward now, hammering out their tattoo with frenzied rhythm. Momentarily forgetting his own advice, he looked behind. Saw Slaughter and next to him, his face covered in mud, his coat splashed with blood and brains from the man who had been killed beside him, yet still smiling through his fear, one of the infants of the company. A boy of barely sixteen. Steel grinned at him. He was a Yorkshire farmhand, if his memory served him right. Runaway, most like. He shouted through the cacophany:

‘Truman, isn’t it? All right lad?’

A bigger smile. That was good.

‘Don’t worry. You’re doing well. Not bad for your first battle. Sarn’t Slaughter, let’s get up there and show them how it’s done.’

Looking to his front he could see nothing but smoke and flying shot. The noise was indescribable. A familiar terror began to rise inside him. Like the sudden, illogical panic that could sweep through you when standing on a precipice. Must stay calm, he thought. The men must not see that I am afraid. There was a cold feeling now in the pit of his stomach. Feet like lead. I am not afraid. He bit his lip until he could taste the blood. Good. He was alive. He would live through this. Just put one foot in front of the other and walk forward. That was it. Slowly he began to advance, and got into an automatic rhythm. Easier now. He raised his sword. It was the right time to say something now. The words flew from him.

‘Grenadiers. Follow me.’

Again they started to climb the slope and with every pace more men fell, as more of the deadly black balls hurtled down towards them. Two hundred yards more now, he guessed. All they had to do was carry on and they’d be there. Just keep going. He was suddenly aware of a change in the rhythm of fire from the defences. Instantly, its cause became evident, as a hail of cannister shot – thirty iron balls blown from the cannon mouth in a canvas bag – slammed into the men standing to his left and took away a score of red-coated bodies. At the same instant a crash of musket fire signalled that the French infantry too had found their range. More men fell. Somewhere, through the drifting smoke to his left, another officer called out:

‘Charge. Charge, boys. God save the Queen.’

Steel saw the man fall, but his cry was taken up along the line and as one, the men broke into a trot. Steel too began to run. Breathing hard now, the smell of powder drifting strong and acrid into his nostrils. They passed through a mist of billowing white smoke. When they emerged on the other side of the cloud however, a sunken gulley appeared directly in front of him – from nowhere. Steel pulled up. He yelled at the men behind him to stop and found himself at the top of a muddy bank of a depth of four, perhaps five feet. Behind him the men came to a halt. All around him, and down along the line, he could hear the frantic shouts of corporals and sergeants. A corporal to his left was giving orders: