полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 577, July 7, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 20, No. 577, July 7, 1827

DOMESTIC ANTIQUITIES

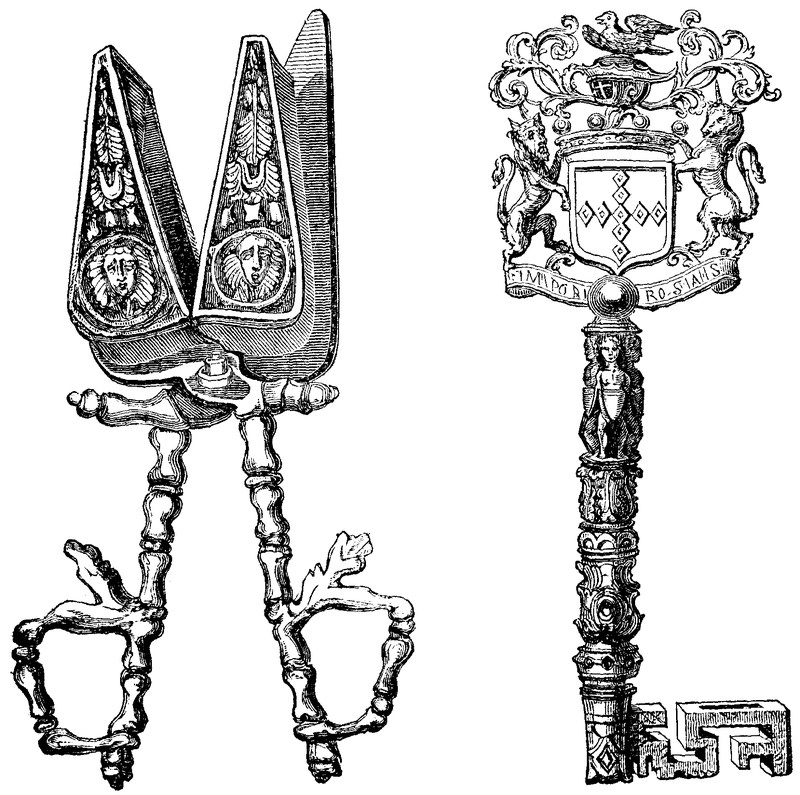

The first of these archæological rarities is a pair of Snuffers, found in Dorsetshire sixty-four years since, and engraved in Hutchins's history of that county. They were discovered, says the historian, "in the year 1768, in digging the foundation of a granary, at the foot of a hill adjoining to Corton mansion house (formerly the seat of the respectable family of the Mohuns), in the parish of St. Peter, Portisham. They are of brass, and weigh six ounces: the great difference between these and the modern utensils of the same nature and use is, that these are in shape like a heart fluted, and consequently terminate in a point. They consist of two equal lateral cavities, by the edges of which the snuff is cut off, and received into the cavities, from which it is not got out without particular application and trouble."

"There are two circumstances attending this little utensil which seem to bespeak it of considerable age: the roughness of the workmanship, which is in all respects as crude and course as can be well imagined, and the awkwardness of the form."

So little is known of the comparatively recent introduction of snuffers into this country, that the above illustration will be acceptable to the observer of domestic origins and antiquities. See also Mirror, vol. xi. p. 74.

The Key, annexed, was the property of Mr. Gough, the eminent topographer, and is supposed to have been used as a passport by some of the family of Stawel, whose arms it bears.

LINES ADDRESSED TO A PARTY OF YOUNG LADIES VISITING THE CATACOMBS AT PARIS

(From the French of M. Emanuel Dupaty.)BY E. B. IMPEY, ESQWhile life is young and pleasure new,Ah! why the shades of Death explore?Better, ere May's sweet prime is o'er,The primrose path of joy pursue:The torch, the lamps' sepulchral fire,Their paleness on your charms impress,And glaring on your loveliness,Death mocks what living eyes desire.Approach! the music of your treadNo longer bids the cold heart beat:For ruling Beauty boasts no seatOf empire o'er the senseless dead!Yet, if their lessons profit aught,Ponder, or ere ye speed away,Those feet o'er flowers were form'd to stray,No death-wrought causeway, grimly wrought,Of ghastly bones and mould'ring clay.To gayer thoughts and scenes arise;Nor ever veil those sun-bright eyesFrom sight of bliss and light of day—Save when in pity to mankindLove's fillet o'er their lids ye bind.HOLLAND

Holland derives its name from the German word Hohl, synonymous with the English term hollow, and denoting a concave, or very hollow, low country.

This country originally formed part of the territory of the Belgæ, conquered by the Romans, 47 years before Christ. A sovereignty, founded by Thierry, first Count of Holland, A.D. 868, continued till the year 1417, when it passed, by surrender, to the Duke of Burgundy. In 1534, being oppressed by the Bishop of Utrecht, the people ceded the country to Spain. The Spanish tyranny being insupportable, they revolted, and formed the republic called the United Provinces, by the Union of Utrecht, 1579. When they were expelled the Low Countries by the Duke of Alva, they retired to England; and having equipped a small fleet of forty sail, under the command of Count Lumay, they sailed towards this coast—being called, in derision, "gueux," or beggars of the sea. Upon the duke's complaining to Queen Elizabeth, that they were pirates, she compelled them to leave England; and accordingly they set sail for Enckhuysen; but the wind being unfavourable, they accidentally steered towards the isle of Voorn, attacked the town of Briel, took possession of it, and made it the first asylum of their liberty.

In 1585, a treaty was concluded between the States of Holland and Queen Elizabeth; and Briel was one of the cautionary towns delivered into her hands for securing the fulfilment of their engagements. It was garrisoned by the English during her reign, and part of the next, but restored to the States in 1616.

The office of Stadtholder, or Captain-General of the United Provinces, was made hereditary in the Prince of Orange's family, not excepting females, 1747. A revolt was formed, but prevented by the Prussians, 1787. The country was invaded by the French in 1793, who took possession of it January, 1795, and expelled the Stadtholder: it was erected into a kingdom by the commands of Buonaparte, and the title of king given to his brother Louis, June 5, 1806. Its changes since this period are familiar to the reader of contemporary history.

Lord Chesterfield, in his Letters to his Son, says—"Holland, where you are going, is by far the finest and richest of the Seven United Provinces, which, altogether, form the republic. The other provinces are Guelderland, Zealand, Friesland, Utrecht, Groningen, and Overyssel. These seven provinces form what is called the States-General of the United Provinces: this is a very powerful, and a very considerable republic. I must tell you that a republic is a free state, without any king. You will go first to the Hague, which is the most beautiful village in the world, for it is not a town. Amsterdam, reckoned the capital of the United Provinces, is a very fine, rich city. There are besides in Holland several considerable towns—such as Dort, Haerlem, Leyden, Delft, and Rotterdam. You will observe throughout Holland the greatest cleanliness: the very streets are cleaner than our houses are here. Holland carries on a very great trade, particularly to China, Japan, and all over the East Indies."

P.T.WTHE HAWTHORN WELL

[The following lines are associated with a singular species of popular superstition which may in some measure, explain the "pale cast of thought" that pervades them. They are written by a native of Northumberland. "The Hawthorn Well," was a Rag Well, and so called from persons formerly leaving rags there for the cure of certain diseases. Bishop Hall, in his Triumphs of Rome, ridicules a superstitious prayer of the Popish Church for the "blessing of clouts in the way of cure of diseases;" and Mr. Brand asks, "Can it have originated thence?" He further observes:—"this absurd custom is not extinct even at this day: I have formerly frequently observed shreds or bits of rag upon the bushes that overhang a well in the road to Benton, a village in the vicinity of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, which, from that circumstance, is now or was very lately called The Rag Well. This name is undoubtedly of long standing: probably it has been visited for some disease or other, and these rag-offerings are the relics of the then prevailing popular superstition."—Brand's Popular Antiquities, vol. ii. p. 270.]

"From hill, from dale, each charm is fled;Groves, flocks, and fountains, please no more."No joy, nor hope, no pleasure, nor its dream,Now cheers my heart. The current of my lifeSeems settled to a dull, unruffled lake,Deep sunk 'midst gloomy rocks and barren hills;Which tempests only stir and clouds obscure;Unbrightened by the cheerful beam of day,Unbreathed on by the gentle western breeze,Which sweeps o'er pleasant meads and through the woods,Stirring the leaves which seem to dance with joy.No more the beauteous landscape in its prideOf summer loveliness—when every treeIs crowned with foliage, and each blooming flowerSpeaks by its breath its presence though unseen—For me has charms; although in early days,Ere care and grief had dulled the sense of joy,No eye more raptured gazed upon the sceneOf woody dell, green slope, or heath-clad hill;Nor ear with more delight drank in the strainsWarbled by cheerful birds from every grove,Or thrilled by larks up-springing to the sky.From the hill side—where oft in tender youthI strayed, when hope, the sunshine of the mind,Lent to each lovely scene, a double charmAnd tinged all objects with its golden hues—There gushed a spring, whose waters found their wayInto a basin of rude stone below.A thorn, the largest of its kind, still greenAnd flourishing, though old, the well o'erhung;Receiving friendly nurture at its rootsFrom what its branches shaded; and aroundThe love-lorn primrose and wild violet grew,With the faint bubbling of that limpid fount.Here oft the shepherd came at noon-tide heatAnd sat him down upon the bank of turfBeneath the thorn, to eat his humble mealAnd drink the crystal from that cooling spring.Here oft at evening, in that placid hourWhen first the stars appear, would maidens comeTo fill their pitchers at the Hawthorn Well,Attended by their swains; and often hereWere heard the cheerful song and jocund laughWhich told of heart-born gladness, and awokeThe slumbering echoes in the distant wood.But now the place is changed. The pleasant path,Which wound so gently up the mountain sideIs overgrown with bent and russet heath;The thorn is withered to a moss-clad stump,And the fox kennels where the turf-bank rose!The primrose and wild violet now no moreSpread their soft fragrance round. The hollow stoneIs rent and broken; and the spring is dry!But yesterday I passed the spot, in thoughtEnwrapped—unlike the fancies which played roundMy heart in life's sweet morning, bright and brief:And as I stood and gazed upon the change,Methought a voice low whispered in my ear:"Thy destiny is linked with that low spring;Its course is changed, and so for aye shall beThe tenor of thy life; and anxious cares,And fruitless wishes, springing without hope,Shall rankle round thy heart, like those foul weedsWhich now grow thick where flow'rets bloomed anew:—Like to that spring, thy fount of joy is dry!"LINES

LAWS RELATING TO BACHELORS

(To the Editor.)At page 53 of the present volume, your Correspondent "E.J.H." in his remarks on "Laws relating to Bachelors," states at the conclusion thereof as follows:—

"In England, bachelors are not left to go forgotten to their solitary graves. There was a tax laid on them by the 7th William III., after the 25th year of their age, which was 12l. 10s. for a duke, and 1s. for a commoner. At present they are taxed by an extra duty upon their servants—for a male, 1l. 5s., for a female, 2s. 6d. above the usual duties leviable upon servants."

Your Correspondent certainly must be in error upon these points, as the additional duty to which bachelors in England are liable under the present Tax Acts, for a male Servant, is only 1l. (the usual duty leviable for such servant being 1l. 4 s.); and there is not, that I am aware of, any law in existence in England taxing any person in respect of female servants.

R.JAlton, Hants.

THE NATURALIST

DEER OF NORTH-AMERICA, AND THE MODE OF HUNTING THEM

(From Featherstonehaugh's Journal.)Deer are more abundant than at the first settlement of the country. They increase to a certain extent with the population. The reason of this appears to be, that they find protection in the neighbourhood of man from the beasts of prey that assail them in the wilderness, and from whose attacks their young particularly can with difficulty escape. They suffer most from the wolves, who hunt in packs like hounds, and who seldom give up the chase until a deer is taken. We have often sat, on a moonlight summer night, at the door of a log-cabin in one of our prairies, and heard the wolves in full chase of a deer, yelling very nearly in the same manner as a pack of hounds. Sometimes the cry would be heard at a great distance over the plain: then it would die away, and again be distinguished at a nearer point, and in another direction;—now the full cry would burst upon us from a neighbouring thicket, and we would almost hear the sobs of the exhausted deer;—and again it would be borne away, and lost in the distance. We have passed nearly whole nights in listening to such sounds; and once we saw a deer dash through the yard, and immediately past the door at which we sat, followed by his audacious pursuers, who were but a few yards in his rear.—Immense numbers of deer are killed every year by our hunters, who take them for their hams and skins alone, throwing away the rest of the carcass. Venison hams and hides are important articles of export; the former are purchased from the hunters at 25 cents a pair, the latter at 20 cents a pound. In our villages we purchase for our tables the saddle of venison, with the hams attached, for 37-1/2 cents, which would be something like one cent a pound.—There are several ways of hunting deer, all of which are equally simple. Most frequently the hunter proceeds to the woods on horseback, in the day-time, selecting particularly certain hours, which are thought to be most favourable. It is said, that, during the season when the pastures are green, this animal rises from his lair precisely at the rising of the moon, whether in the day or night; and I suppose the fact to be so, because such is the testimony of experienced hunters. If it be true, it is certainly a curious display of animal instinct. This hour is therefore always kept in view by the hunter, as he rides slowly through the forest, with his rifle on his shoulder, while his keen eye penetrates the surrounding shades. On beholding a deer, the hunter slides from his horse, and, while the deer is observing the latter, creeps upon him, keeping the largest trees between himself and the object of pursuit, until he gets near enough to fire. An expert woodsman seldom fails to hit his game. It is extremely dangerous to approach a wounded deer. Timid and harmless as this animal is at other times, he no sooner finds himself deprived of the power of flight, than he becomes furious, and rushes upon his enemy, making desperate plunges with his sharp horns, and striking and trampling furiously with his forelegs, which, being extremely muscular and armed with sharp hoofs, are capable of inflicting very severe wounds. Aware of this circumstance, the hunter approaches him with caution, and either secures his prey by a second shot, where the first has been but partially successful, or, as is more frequently the case, causes his dog to seize the wounded animal, while he watches his own opportunity to stab him with his hunting-knife. Sometimes where a noble buck is the victim, and the hunter is impatient or inexperienced, terrible conflicts ensue on such occasions. Another mode is to watch at night, in the neighbourhood of the salt-licks. These are spots where the earth is impregnated with saline particles, or where the salt-water oozes through the soil. Deer and other grazing animals frequent such places, and remain for hours licking the earth. The hunter secretes himself here, either in the thick top of a tree, or most generally in a screen erected for the purpose, and artfully concealed, like a mask-battery, with logs or green boughs. This practice is pursued only in the summer, or early in the autumn, in cloudless nights, when the moon shines brilliantly, and objects may be readily discovered. At the rising of the moon, or shortly after, the deer having risen from their beds approach the lick. Such places are generally denuded of timber, but surrounded by it; and as the animal is about to emerge from the shade into the clear moonlight, he stops, looks cautiously around and snuffs the air. Then he advances a few steps, and stops again, smells the ground, or raises his expanded nostrils, as if "he snuffed the approach of danger in every tainted breeze." The hunter sits motionless, and almost breathless, waiting until the animal shall get within rifle-shot, and until its position, in relation to the hunter and the light, shall be favourable, when he fires with an unerring aim. A few deer only can be thus taken in one night, and after a few nights, these timorous animals are driven from the haunts which are thus disturbed. Another method is called driving, and is only practised in those parts of the country where this kind of game is scarce, and where hunting is pursued as an amusement. A large party is made up, and the hunters ride forward with their dogs. The hunting ground is selected, and as it is pretty well known what tracts are usually taken by the deer when started, an individual is placed at each of those passages to intercept the retreating animal. The scene of action being in some measure, surrounded, small parties advance with the dogs in different directions, and the startled deer, in flying, generally fly by some of the persons who are concealed, and who fire at them as they pass.

WOLVES OF NORTH AMERICA

(From Featherstonehaugh's Journal.)Wolves are very numerous in every part of the state. There are two kinds: the common or black wolf, and the prairie wolf. The former is a large, fierce animal, and very destructive to sheep, pigs, calves, poultry, and even young colts. They hunt in large packs, and after using every stratagem to circumvent their prey, attack it with remarkable ferocity. Like the Indian, they always endeavour to surprise their victim, and strike the mortal blow without exposing themselves to danger. They seldom attack man except when asleep or wounded. The largest animals, when wounded, entangled, or otherwise disabled, become their prey, but in general they only attack such as are incapable of resistance. They have been known to lie in wait upon the bank of a stream, which the buffaloes were in the habit of crossing, and, when one of those unwieldy animals was so unfortunate as to sink in the mire, spring suddenly upon it and worry it to death, while thus disabled from resistance. Their most common prey is the deer, which they hunt regularly; but all defenceless animals are alike acceptable to their ravenous appetites. When tempted by hunger, they approach the farm-houses in the night, and snatch their prey from under the very eye of the farmer; and when the latter is absent with his dogs, the wolf is sometimes seen by the females lurking about in mid-day, as if aware of the unprotected state of the family. Our heroic females have sometimes shot them under such circumstances. The smell of burning assafœtida has a remarkable effect upon this animal. If a fire be made in the woods, and a portion of this drug thrown into it, so as to saturate the atmosphere with the odour, the wolves, if any are within the reach of the scent, immediately assemble around, howling in the most mournful manner; and such is the remarkable fascination under which they seem to labour, that they will often suffer themselves to be shot down rather than quit the spot. Of the very few instances of their attacking human beings of which we have heard, the following may serve to give some idea of their habits. In very early times, a Negro man was passing in the night in the lower part of Kentucky from one settlement to another. The distance was several miles, and the country over which he travelled entirely unsettled. In the morning, his carcass was found entirely stripped of flesh. Near it lay his axe, covered with blood, and all around, the bushes were beaten down, the ground trodden, and the number of foot-tracks so great, as to show that the unfortunate victim had fought long and manfully. On following his track, it appeared that the wolves had pursued him for a considerable distance; and that he had often turned upon them and driven them back. Several times they had attacked him, and been repelled, as appeared by the blood and tracks. He had killed some of them before the final onset, and in the last conflict had destroyed several; his axe was his only weapon. The prairie wolf is a smaller species, which takes its name from its habits, or residing entirely upon the open plains. Even when hunted with dogs, it will make circuit after circuit round the prairie, carefully avoiding the forest, or only dashing into it occasionally when hard pressed, and then returning to the plain. In size and appearance this animal is midway between the wolf and the fox, and in colour it resembles the latter, being of a very light red. It preys upon poultry, rabbits, young pigs calves, &c. The most friendly relations subsist between this animal and the common wolf, and they constantly hunt in packs together. Nothing is more common than to see a large, black wolf in company with several prairie wolves. I am well satisfied that the latter is the jackall of Asia. Several years ago, an agricultural society, which was established at the seat of government, offered a large premium to the person who should kill the greatest number of wolves in one year. The legislature, at the same time offered a bounty for each wolf-scalp that should be taken. The consequence was, that the expenditure for wolf-scalps became so great, as to render it necessary to repeal the law. These animals, although still numerous, and troublesome to the farmer, are greatly decreased in number, and are no longer dangerous to man. We know of no instances in late years of a human being having been attacked by wolves.

CEDAR TREES

There are now growing on the grounds of Greenfield Lodge, two cedar trees of the immense height of 150 feet; the girth of one is 11 ft. 7 in. and its branches extend 50 feet; the girth of the other is 8 ft. 7 in.—Chester Chronicle.

GIGANTIC WHALE

The skeleton of the whalebone whale which was cast ashore at North Berwick last year, and whose measurement so far exceeds the ordinary dimensions of animated nature as positively to require to be seen before being believed, is now in course of preparation, and we believe will be set up in such a manner as to enable scientific men to examine it with every advantage. The baleen (commonly called whalebone) has been prepared with infinite care and trouble, and will be placed in its original section in the palate. If there be one part more remarkable than another, it is the appearance of the baleen, or whalebone, when occupying its natural position; the prodigious quantity (upwards of two tons), and, at the same time, mechanical beauty connected with every part of the unique mass, rendering it beyond the power of language to describe, or give the slightest idea of it. The skull, or brainbone, was divided vertically, with a view to convenience in moving the head (this portion of the skeleton weighing eight tons). This section displayed the cavity for containing the brain; and thus some knowledge of the sentient and leading organ of an animal, the dimensions of whose instruments of motion fill the mind with astonishment, will at last be obtained. Results, unexpected, we believe, by most anatomists were arrived at. The cavity (a cast of which will be submitted to the anatomical public) was gauged or measured in the manner first invented and recommended by Sir William Hamilton, and under that gentleman's immediate inspection; the weight of the brain, estimated in this way, amounts to 54 lb. imperial weight. The brain of the small whalebone whale, examined by Mr. Hunter (the specimen was only 17 feet long), weighed about 4 lb. 10 oz.; the brain of the elephant weighs between 6 lb. and 7 lb.; the human brain from 3 lb. to 4 lb. The total length of the whale was 80 feet; and although Captain Scoresby mentions one which he heard of which was said to measure somewhat more than 100 feet, it is extremely probable that this measurement had not been taken correctly. The whale examined by Sir Robert Sibbald, nearly a century ago, measured exactly 78 feet; "fourteen men could stand at one time in the mouth; when the tide rose, a small boat full of men entered easily."—Scotsman.