полная версия

полная версияThe Bay State Monthly, Volume 3, No. 1

"My mother remembers her love vnto yor father and mother; as also vnto your selfe though as it vnknown.

"Yors to command in anything I pleas.

"JOHN CAPEN."

In this connection may very properly be given another letter written at about the same date. Punkapoag, the summer residence of Thomas Bailey Aldrich, the poet editor of the Atlantic, was a part of colonial Dorchester and one of the points where the famous John Eliot began his missionary labors among the Indians. In the interest of the natives at that station he wrote the following letter to his friend, Major Atherton, in 1657:

"Much Honored and Beloved in the Lord:

"Though our poore Indians are molested in most places in their meetings in way of civilities, yet the Lord hath put it into your hearts to suffer us to meet quietly at Ponkipog, for wch I thank God, and am thankful to yourselfe and all the good people of Dorchester. And now that our meetings may be the more comfortable and p varable, my request is, yt you would further these two motions: first, yt you would please to make an order in your towne and record it in your towne record, that you approve and allow ye Indians of Ponkipog there to sit downe and make a towne, and to inioy such accommodations as may be competent to maintain God's ordinances among them another day. My second request is, yt you would appoint fitting men, who may in a fitt season bound and lay out the same, and record yt alsoe. And thus commending you to the Lord, I rest,

"Yours to serve in the service of Jesus Christ,

"JOHN ELIOT."

Following this missive a letter on quite a different subject, dictated by the redoubtable Indian chief, King Philip, may be interesting. It bears date of 1672, and is addressed to Captain Hopestill Foster of Dorchester:

"Sr you may please to remember that when I last saw You att Walling river You promised me six pounds in goods; now my request is that you would send me by this Indian five yards of White light collered serge to make me a coat and a good Holland shirt redy made; and a pr of good Indian briches all of which I have present need of, therefoer I pray Sr faile not to send them by my Indian and with them the severall prices of them; and silke & buttens & 7 yards Gallownes for trimming; not else att present to trouble you wth onley the subscription of

"KING PHILIP,

"his Majesty P.P."

One of the best commentaries on the lives and characters of the chief actors in the history of the Dorchester Plantation may be read on the tombstones that mark the places where their precious dust was deposited. From Rev. Richard Mather, the most noted pastor of the church of that period, to the humblest contemporary of his who enjoyed the rights and priveleges of a free-holder, none was so mean or obscure that a characteristic, if not fitting, epitaph did not mark the place of his sepulture. From the many well worth perusing, the following are singled and transcribed for the readers of this sketch.

Epitaph of James Humfrey, "one of ye ruling elders of Dorchester," in the form of an acrostic:

"I nclos'd within this shrine is precious dust.A nd only waits ye rising of ye just.M ost usefull while he liu'd, adorn'd his Station,E uen to old age he Seur'd his Generation.H ow great a Blessing this Ruling Elder beU nto the Church & Town: & Pastors Three.M ather he first did by him help Receiue;F lynt did he next his burden much Relieue;R enouned Danforth he did assist with Skill:E steemed high by all; Bear fruit Untill,Y eilding to Death his Glorious seat did fill."When Elder Hopestill Clapp died his pastor, Rev. John Danforth, composed the following verses for his grave stone:

"His Dust waits till ye Jubile,Shall then Shine brighter than ye Skie;Shall meet and join to part no more,His soul that Glorify'd before.Pastors and Churches happy be,With Ruling Elders such as he;Present useful, Absent Wanted,Liv'd Desired, Died Lamented."William Pole, an eccentric citizen of the village, before his demise, composed an epitaph to be chiseled on his monument, "Yt so being dead he might warn posterity; or, a resemblance of a dead man bespeaking ye reader;" so under a death's head and cross-bones it stands thus:

"Ho passenger 'tis worth your paines to stay& take a dead man's lesson by ye way.I was what now thou art & thou shall beWhat I am now what odds twixt me and theeNow go thy way but stay take one word moreThy staff for ought thou knowest stands next ye doorDeath is ye dore yea dore of heaven or hellBe warned, Be armed, Believe, Repent, Fairewell."The virtues of one who was "downright for business, one of cheerful spirit and entire for the country" are recorded in this fashion:

"Here lyes ovr Captaine, & Major of Suffolk was withall:A Goodley Magistrate was he, and Major Generall,Two Troops of Hors with him here came, svch worth his loue did crave;Ten Companyes of Foot also movrning marcht to his grave.Let all that Read be sure to Keep the Faith as he has don.With Christ his liues now, crowned, his name was Hvmfrey Atherton."The following was written on the death of John Foster, who is mentioned in the old annals as a "mathematician and printer":

"Thy body which no activeness did lack,Now's laid aside like an old Almanack;But for the present only's out of date,'Twill have at length a far more active state.Yes, tho' with dust thy body soiled be.Yet at the resurrection we shall seeA fair EDITION, and of matchless worth.Free from ERRATAS, new in Heaven set forth.'Tis but a word from God the great Creator,It shall be done when he saith Imprimator."The clerk of the old Dorchester Church seems also to have been a maker of elegiac verse; for after the decease of Rev. Richard Mather, the pastor, and one of the ablest divines of colonial New England, the church records contain the two complimentary stanzas quoted below, the first being an evident attempt at anagram:

"Third in New England's Dorchester,Was this ordained minister.Second to none for faithfulness,Abilities and usefulness.Divine his charms, years seven times seven,Wise to win souls from earth to heaven.Prophet's reward his gains above,But great's our loss by his remove."Sacred to God his servant Richard Mather,Sons like him, good and great, did call him father.Hard to discern a difference in degree,'Twixt his bright learning and his piety.Short time his sleeping dust lies covered down,So can't his soul or his deserved renown.From 's birth six lustres and a jubileeTo his repose: but labored hard in thee,O, Dorchester! four more than thirty yearsHis sacred dust with thee thine honour rears."This couplet to three brothers named Clarke must suffice for epitaphs:

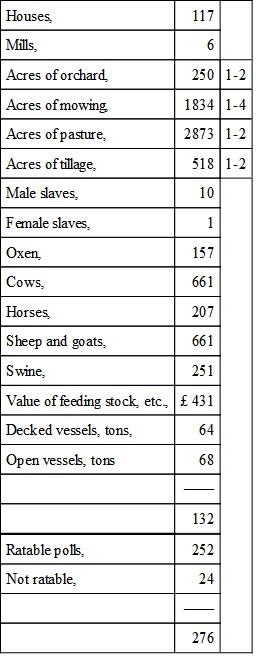

"Here lie three Clarkes, their accounts are even,Entered on earth, carried up to Heaven."Before taking leave of these fascinating old records, so rich in facts and the stuff that fiction is made of, it will be interesting to have an estimate of the growth of the Dorchester Plantation; for this purpose the valuation of the town is given, a century from the date of its settlement:

The tax for that year, assessed on real estate, was £72 16s 6d; on personal estate, £9 14s 11d.

When all who took up the original claims on Allen's Plain had passed through the vicissitudes of their troubled lives and been numbered with the silent majority in the field of epitaphs, already alluded to, and their descendents were on the eve of the great struggle which was destined to sever them from the mother country, and the hearts of patriotic men began to feel the premonitory throbs of that spirit of independence soon to fire the first shot at Lexington, the Union and Association of Sons of Liberty in the province held a grand celebration in Boston, on the fourteenth of August, 1769. From John Adams's famous diary we learn that this jovial company, including the leading spirits of the time, first assembled at Liberty Tree, in Boston, where they drank fourteen toasts, and then adjourned to Liberty Tree Tavern, which was none other than Robinson's Tavern in Dorchester. There under a mammoth tent in an adjacent field long tables were spread, and over three hundred persons sat down to a sumptuous dinner. "Three large pigs were barbecued," and "forty-five toasts were given on the occasion," the last of which was, "Strong halters, firm blocks and sharp axes to all such as deserve them." The toasts were varied with songs of liberty and patriotism by a noted colonial mimic named Balch, and another song composed and sung by Dr. Church. "At five o'clock," says Mr. Adams, "the Boston people started home, led by Mr. Hancock in his chariot, and to the honour of the Sons, I did not see one person intoxicated."

HOLLIS STREET CHURCH

The demolition of Hollis Street Church in this city destroys another old historic land-mark, which, like King's Chapel, the old State House, and other venerable structures, have a record that endears them to the popular heart. A brief sketch of the three buildings which have successively occupied the site, which is so soon to be left vacant, is worthy of preservation.

The name of the church and the street on which it stood was bestowed in honor of Thomas Hollis, of London, noted for his liberal benefactions; and his nephew of the same name devoted a bell for the edifice, in 1734.

The land on which the original structure was erected, was presented for that purpose by Governor Belcher, in 1731; and in April of the same year, by permission of the selectmen of Tri-Mountain, or Boston, a wooden building, sixty feet long and forty feet wide, was began, which was finished and dedicated in midsummer of the following year.

In the great South End fire, on the twentieth of April, 1787, and in response to an imperative demand, a second, and larger wooden house, was erected on the site of the first, and made ready for occupancy in the course of the following year. This building was planned by Charles Bulfinch, and in its architecture resembled St. Paul's Church, now standing on Tremont street.

Within a year the Hollis Street Society has removed to an elegant new edifice on the Back Bay, and the brick building they left behind must now disappear in the march of improvement. It was erected in 1811, in order to accommodate the prosperous and rapidly-growing society for whom it stood as a place of worship. To make room for it, the wooden meeting-house already referred to was taken down in sections and removed to the town of Braintree.

The several clergymen who have been the honored pastors of Hollis Street Church are worthy of mention in this connection. The first was Rev. Mather Byles, a lineal descendant of John Cotton and Richard Mather, who was ordained pastor, December 20, 1732. He was dismissed August 14, 1776, on account of his strong Tory proclivities. His immediate successor was Rev. Ebenezer Wright, a young divine from Dedham and a graduate of Harvard, who remained the pastor until the new meeting-house was finished, in 1788, when he was dismissed at his own request, on account of ill-health.

The next pastor was a man in middle life, who made himself an acknowledged power among the Boston clergy, Rev. Samuel West, of Needham. He died in 1808, and was succeeded by Rev. Horace Holley, from Connecticut, who was installed in March, 1809, and remained till 1818. Rev. John Pierpont, who resigned in 1845, made way for Rev. David Fosdick, who preached there two years, when Rev. Starr King was settled in 1845, and remained till 1861, Rev. George L. Chaney then took the place till 1877, and was succeeded by Rev. H. Bernard Carpenter, the present pastor.

ELIZABETH.13

CHAPTER XIII.—Continued

Half an hour later Edmonson marched into his friend's room. His face was flushed, and his eyes had a triumphant glitter. It was an expression that heightened most the kind of beauty he had.

"You are booked for a visit, Bulchester," he began, seating himself in the chair opposite the other. "I have accepted for you; knew you would be glad to go with me."

"That is cool!" And Bulchester's light blue eyes glowed with anger for a moment. His moods of resentment against his companion's domination, though few and far between, were very real.

"Not at all. In fact it is a delightful place, and I don't know to what good fortune we are indebted for an invitation. Neither of us has much acquaintance with Archdale."

"Archdale? Stephen Archdale?"

"Yes. You look amazed, man. We are asked to meet Sir Temple and Lady Dacre. I don't exactly see how it came about, but I do see that it is the very thing I want in order to go on with the search. Another city, other families."

"But—." Bulchester stopped.

"But what?"

"Why, the possible Mistress Archdale,—Elizabeth. Of course I am happy to go, if you enjoy the situation."

A dangerous look rayed out from Edmonson's eyes.

"I can stand it, if Archdale can," he answered. "How fate works to bring us together," he mused.

"I don't understand," cried the other. "What has fate to do with this invitation?" Edmonson, who had spoken, forgetting that he was not alone, looked at his companion with sudden suspicion. But Bulchester went on in the same tone. "If it is to carry out your purpose though, little you will care for having been a suitor of Mistress Archdale."

"On the contrary, it will add piquancy to the visit." Then he added, "Don't you see, Bulchester, that I dare not throw away an opportunity? Ship 'Number One' has foundered. 'Number Two' must come to land. That is the amount of it."

"Yes," returned Bulchester with so much assurance that the other's scrutiny relaxed.

"I suppose it is settled," said his lordship after a pause.

"Certainly," answered Edmonson; and he smiled.

Lady Dacre and train, having fairly started on their two day's journey, she settled herself luxuriously and again began her observations. But as they were not especially striking, no chronicle of them can be found, except that she called Brattle Street an alley, begged pardon for it with a mixture of contrition and amusement, and generally patronized the country a little. Sir Temple enjoyed it greatly, and Archdale was glad of any diversion. When they had stopped for the night, as they sat by the open windows of the inn and looked out into the garden which was too much a tangle for anything but moonlight and June to give it beauty, Lady Dacre sprang up, interrupting her husband in one of his remarks, and declaring it a shame to stay indoors such a night.

"Give me your arm," she said to Archdale, "and let us take a turn out here. We don't want you, Temple; we want to talk."

Sir Temple, serenely sure of hearing, before he slept, the purport of any conversation that his wife might have had, took up a book which he had brought with him. He was an excellent traveler in regard to one kind of luggage; the same book lasted him a good while.

Lady Dacre moved off with Stephen. They went out of the house and down the walk. She commented on the neglected appearance of things until Stephen asked her if weeds were peculiar to the American soil. In answer she struck him lightly with her fan and walked on laughing. But when they reached the end of the garden, she turned upon him suddenly.

"Now tell me," she said.

"Tell you what?"

"Tell me what, indeed! What a speech for a lover, a young husband. Has the light of your honeymoon faded so quickly? Mine has not yet. Tell me about her, of course, your charming bride."

Stephen came to a dead halt, and stood looking into the smiling eyes gazing up into his.

"Lady Dacre," he said, "the Mistress Archdale you will find at Seascape is my mother." Then he gave the history of his intended marriage, and of that other marriage which might prove real. His listener was more moved than she liked to show.

"It will all be right," she said tearfully. "But it is dreadful for you, and for the young ladies, both of them."

"Yes," he answered, "for both of them."

"You know," she began eagerly, "that I am the–?" then she stopped.

Stephen waited courteously for the end of the sentence that was never to be finished. He felt no curiosity at her sudden breaking off; it seemed to him that curiosity and interest, except on one subject, were over for him forever.

When Lady Dacre repeated this story to her husband she finished by saying: "Why do you suppose it is, Temple, that my heart goes out to the married one?"

"Natural perversity, my dear."

"Then you think she is married?"

"Don't know; it is very probable."

"Poor Archdale!"

Sir Temple burst into a laugh. "Is he poor, Archdale, because you think he has made the best bargain?"

"No, you heartless man, but because he does not see it. Besides, I cannot even tell if it is so. I believe I pity everybody."

"That's a good way," responded her husband. "Then you will be sure to hit right somewhere."

"I will remember that," returned Lady Dacre between vexation and laughing, "and lay it up against you, too. But, poor fellow, he is so in love with his pretty cousin, and she with him."

"Poor cousin! Is she like a certain lady I know who chose to be married in a dowdy dress and a poke bonnet for fear of losing her husband altogether?"

But Lady Dacre did not hear a word. She was listening to a mouse behind the wainscotting, and spying out a nail-hole which she was sure was big enough for it to come out of, and she insisted that her husband should ring and have the place stopped up.

When the party reached Seascape the summer clouds that floated over the ocean were beginning to glow with the warmth of coming sunset. The sea lay so tranquil that the flash of the waves on the pebbly shore sounded like the rythmic accompaniment to the beautiful vision of earth and sky, and the boom of the water against the cliffs beyond came now and then, accentuating this like the beat of a heavy drum muffled or distant. The mansion at Seascape with its forty rooms, although new, was so substantial and stately that as they drove up the avenue Lady Dacre, accustomed to grandeur, ran her quick eye over its ample dimensions, its gambrel roof, its immense chimneys, its generous hall door, and turning to Archdale, without her condescension, she asked him how he had contrived to combine newness and dignity.

"One sees it in nature sometimes," he answered. "Dignity and youth are a fascinating combination."

In the hall stood a lady whom Archdale looked at with pride. He was fond of his mother without recognizing a certain likeness between them. She was dressed elegantly, although without ostentation, and she came towards her guests with an ease as delightful as their own. Stephen going to meet her, led her forward and introduced her. Lady Dacre looked at her scrutinizingly, and gave a little nod of satisfaction.

"I am pleased to come to see you Madam Archdale," she said in answer to the other's greeting. There was a touch of sadness in her face and the clasp of her hand had a silent sympathy in it. It was as if the two women already made moan over the desolation of the man in whom they both were interested, though in so different degrees. But the tact of both saved awkwardness in their meeting.

Archdale stood a little apart, silent for a moment, struggling against the overwhelming suggestions of the situation. Even his mother did not belong here; she had her own home. Perhaps it would be found that no woman for whom he cared could ever have a right in this lovely house. When these guests had gone he would shut up the place forever, unless–. But possibilities of delight seemed very vague to Stephen as he stood there in his home unlighted by Katie's presence. All at once he felt a long keen ray from Sir Temple's eyes upon his face. That gentleman had a fondness for making out his own narratives of people and things; he preferred Mss. to print, that is, the Mss. of the histories he found written on the faces of those about him, which, although sometimes difficult to decipher, had the charm of novelty, and often that of not being decipherable by the multitude. Stephen immediately turned his glance upon Sir Temple.

"You are tired," he said with decision, "and Lady Dacre must be quite exhausted, animated as she looks. But I see that my mother is already leading her away. Let me show you your rooms."

Sir Temple's eyes had fallen, and with a bow and a half smile upon his lips, he walked beside his host in silence.

CHAPTER XIV

THE HOSTESSThe second morning of the visit was delightful. Madam Archdale had taken Lady Dacre to the cupola, and the view that met their eyes would have more admiration from people more travelled than these. On the east was the sea, looking in the early sunshine like a great flashing crescent of silver laid with both its arcs upon the earth. Down to it wandered the creek winding by the grounds beneath the watchers, turned out of its straight course, now to lave the foot of some large tree that in return spread a circle of shade to cool its waters before they passed out under the hot sun again; now to creep through some field, perhaps of daises, to send its freshness through all their roots and renew their courage in the contest with the farmers, so that the more they were cut down, the more they flourished, for the sun, and the stream, the summer air, and the soil, all were upon their side. Shadows fell upon the water from the bridge across the road over which the lumbering carts went sometimes, and the heavy carriages still more seldom. On the other hand, looking up the stream, were the hills from among which this little river slipped out rippling along with its musical undertone, as if they had sent it as a messenger to express their delight in summer. In the distance the Piscataqua broadened out to the sea, and beyond the river the city was outlined against the sky. To the left of this, and in great sweeps along the horizon stretched the forests. As one looked at these forests, the fields of com, the scattered houses, the pastures dotted with cattle, the city, all signs of civilization, seemed like a forlorn hope sent against these dense barriers of nature; yet it was that forlorn hope that is destined always to win.

"Do you know, I like it?" said Lady Dacre turning to her hostess. "I think it all very nice. So does Sir Temple. Yet I don't see how you can get along without a bit of London, sometimes. London is the spice, you know, the flavor of the cake, the bouquet of the wine."

"Only, it differs from these, since one cannot get too much of it," answered Madam Archdale smiling, thinking as her eyes swept over the landscape that there were charms in her own land which it would be hard to lose.

Lady Dacre settled herself comfortably in one of the chairs of the cupola, and turning to her companion, said abruptly:

"Dear Madam Archdale, what is going to be done about that poor son of yours; he is in a terrible situation?"

"Indeed, he is."

"When is he going to get out? Have you done anything about it?"

"Done anything? Everything, rather. To say nothing of Stephen and my poor little niece. Elizabeth Royal is not a woman to sit down calmly under the imputation of having married a man against his will. And, besides, I have heard that she would like to marry one of her suitors."

"Do you know him?"

"Not even who it is. I imagine that Stephen does, but he does not tell all he knows."

"I have found that out," laughed Lady Dacre. "Indeed, I don't feel like laughing," she added quickly, "but it seems to me only an awkward predicament, you see, and I am thinking of the time when the young people will be free to tie themselves according to their fancies.

"I don't take it so lightly," answered the lady, "and my husband, when Stephen is out of the way, shakes his head dolefully over it. He believes Harwin's story, and in that case he argues badly. My husband has a conscience, and he does not intend that his son shall commit bigamy. Neither does Stephen, of course, intend to; but then, Stephen is in love with Katie, and he and Elizabeth Royal are disposed to carry matters with a high hand. But Katie has scruples, too, and she must, of course, be satisfied."

"Of course. What kind of person is this Elizabeth Royal?" asked Lady Dacre after a pause. "Is she pretty, or plain?"

"Not plain, certainly. She has a kind of beauty at times, a beauty of expression quite remarkable, Katie tells me. But I have not seen anything especial about her."