полная версия

полная версияModern India

The sacred thread is even of greater importance in Hinduism, and the Brahmins require that each child shall be invested with it in his eighth year. Until that year also he must bear upon his forehead the sign of his caste, which Ryas, our bearer, calls "the god mark." The sacred thread is a fine silk cord, fastened over the left shoulder, hanging down under the right arm like a sash. None but the two highest castes have the right to wear it, although members of the lower castes are even more careful to do so. It is put on a child by the priest or the parent on its eighth birthday with ceremonies similar and corresponding to those of our baptism. After the child has been bathed and its head has been carefully shaved it is dressed in new garments, the richest that the family can afford. The priest or godfather ties on the sacred thread and teaches the child a brief Sanskrit text called a mantra, some maxim or proverb, or perhaps it may be only the name of a deity which is to be kept a profound secret and repeated 108 times daily throughout life. The deity selected serves the child through life as a patron saint and protector. Frequently the village barber acts in the place of a priest and puts on the sacred thread. A similar thread placed around the neck of a child, and often around its waist by the midwife immediately after birth, is intended as an amulet or charm to protect from disease and danger. It is usually a strand of silk which has been blessed by some holy man or sanctified by being placed around the neck of an idol of recognized sanctity.

The streets of the native quarters of Indian cities are filled with naked babies and children. It is unfashionable for the members of either sex to wear clothing until they are 8 or 10 years old. The only garment they wear is the sacred string, with usually a little silver charm or amulet suspended from it. Sometimes children wear bracelets and anklets of silver, which tinkle as they run about the streets. The little rascals are always fat and chubby, and their bright black eyes give them an appearance of unnatural intelligence. The children are never shielded from the sun, although its rays are supposed to be fatal to full grown and mature persons. Their heads being shaved, the brain is deprived of its natural protection, and they never wear hats or anything else, and play all day long under the fierce heat in the middle of the road without appearing any the worse for it, although foreign doctors insist that this exposure is one of the chief causes of the enormous infant mortality in India. This may be true, because a few days after birth babies are strapped upon the back of some younger child or are carried about the streets astride the hips of their mothers, brothers or sisters without any protection from the sun.

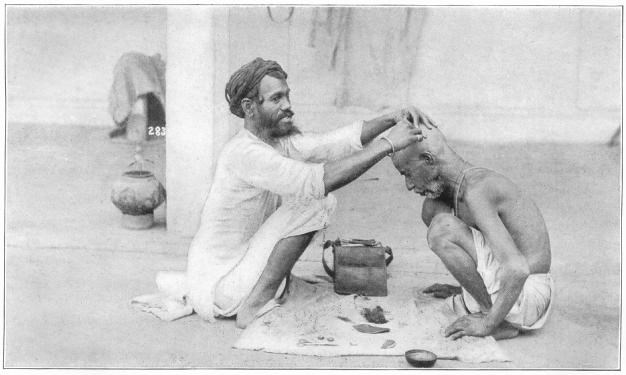

A HINDU BARBER

All outdoors is an Indian barber-shop. The barbers have no regular places of business, but wander from house to house seeking and serving customers, or squat down on the roadside and intercept them as they pass. In the large cities you can see dozens of them squatting along the streets performing their sacred offices, shaving the heads and oiling the bodies of customers. Cocoanut oil is chiefly used and is supposed to add strength and suppleness to the body. It is administered with massage, thoroughly rubbed in and certainly cannot injure anybody. In the principal parks of Indian cities, at almost any time in the morning, you can see a dozen or twenty men being oiled and rubbed down by barbers or by friends, and a great deal of oil is used in the hair. After a man is grown he allows his hair to grow long and wears it in a knot at the back of his head. Some Hindus have an abundance of hair, of which they are very proud, and upon which they spend considerable care and labor.

The parks are not only used for dressing-rooms, but for bedrooms also. Thousands of people sleep in the open air day and night, stretched full length upon the ground. They wrap their robes around their heads and leave their legs and feet uncovered. This is the custom of the Indians of the Andes. No matter how cold or how hot it may be they invariably wrap the head and face up carefully before sleeping and leave the lower limbs exposed. A Hindu does not care where he sleeps. Night and day are the same to him. He will lie down on the sidewalk in the blazing sunshine anywhere, pull his robe up over his head and sleep the sleep of the just. You can seldom walk a block without seeing one of these human bundles all wrapped up in white cotton lying on the bare stone or earth in the most casual way, but they are very seldom disturbed.

You have to get up early in the morning to see the most interesting sights in Benares, which are the pilgrims engaged in washing their sins away in the sacred but filthy waters of the Ganges, and the outdoor cremation of the bodies of people who have died during the night and late in the afternoon of the preceding day. Hindus allow very little time between death and cremation. As soon as the heart ceases to beat the undertakers, as we would call the men who attend to these arrangements, are sent for and preparation for the funeral pyre is commenced immediately. Three or four hours only are necessary, and if death occurs later than 1 or 2 o'clock in the afternoon the ceremony must be postponed until morning. Hence all of the burning ghats along the river bank are busy from daylight until mid-day disposing of the bodies of those who have died during the previous eighteen or twenty hours.

The death rate in Benares is very high. Under ordinary circumstances it is higher than that of other cities of India because of its crowded and unsanitary condition, and because all forms of contagious diseases are brought by pilgrims who come here themselves to die. As I have already told you, it is the highest and holiest aspiration of a pious Hindu to end his days within an area encircled by what is known as the Panch-Kos Road, which is fifty miles in length and bounds the City of Benares. It starts at one end of the city at the river banks, and the other terminus is on the river at the other end. It describes a parabola. As the city is strung along the bank of the river several miles, it is nowhere distant from the river more than six or seven miles. All who die within this boundary, be they Hindu or Christian, Mohammedan or Buddhist, pagan, agnostic or infidel, or of any other faith or no faith, be they murderers, thieves, liars or violators of law, and every caste, whatever their race, nationality or previous condition, no matter whether they are saints or sinners, they cannot escape admission to Siva's heaven. This is the greatest possible inducement for people to hurry there as death approaches, and consequently the non-resident death rate is abnormally high.

We started out immediately after daylight and drove from the hotel to the river bank, where, at a landing place, were several boats awaiting other travelers as well as ourselves. They were ordinary Hindu sampans–rowboats with houses or cabins built upon them–and upon the decks of our cabin comfortable chairs were placed for our party. As soon as we were aboard the boatmen shoved off and we floated slowly down the stream, keeping as close to the shore as possible without jamming into the rickety piers of bamboo that stretched out into the water for the use of bathing pilgrims.

The bank of the river is one of the most picturesque and imposing panoramas you can imagine. It rises from the water at a steep grade, and is covered with a series of terraces upon which have been erected towers, temples, mosques, palaces, shrines, platforms and pavilions, bathing-houses, hospices for pilgrims, khans or lodging-houses, hospitals and other structures for the accommodation of the millions of people who come there from every part of India on religious pilgrimages and other missions. These structures represent an infinite variety of architecture, from the most severe simplicity to the fantastic and grotesque. They are surmounted by domes, pinnacles, minarets, spires, towers, cupolas and canopies; they are built of stone, marble, brick and wood; they are painted in every variety of color, sober and gay; the balconies and windows of many of them are decorated with banners, bunting in all shapes and colors, festoons of cotton and silk, garlands of flowers and various expressions of the taste and enthusiasm of the occupants or owners.

From the Sparrow Hills at Moscow one who has sufficient patience can count 555 gilded and painted domes; from the cupola of St. Peter's one may look down upon the roofs of palaces, cathedrals, columns, obelisks, arches and ruins such as can be seen in no other place; around the fire tower at Pera are spread the marvelous glories of Stamboul, the Golden Horn and other parts of Constantinople; from the citadel at Cairo you can have a bird's-eye view of one of the most typical cities of the East; from the Eiffel Tower all Paris and its suburbs may be surveyed, and there are many other striking panoramas of artificial scenery, but nothing on God's footstool resembles the picture of the holy Hindu city that may be seen from the deck of a boat on the Ganges. It has often been described in detail, but it is always new and always different, and it fascinates its witnesses. There is a repulsiveness about it which few people can overcome, but it is unique, and second only to the Taj Mahal of all the sights in India.

A bathing ghat is a pavilion, pier or platform of stone covered with awnings and roofs to protect the pilgrims from the sun. It reaches into the river, where the water is about two feet deep, and stone steps lead down to the bottom of the stream. Stretching out from these ghats, in order to accommodate a larger number of people, are wooden platforms, piers of slender bamboo, floats and all kinds of contrivances, secure and insecure, temporary and permanent, which every morning are thronged with pilgrims from every part of India in every variety of costumes, crowding in and out of the water, carrying down the sick and dying, all to seek salvation for the soul, relief for the mind and healing for the body which the Holy Mother Ganges is supposed to give.

The processions of pilgrims seem endless and are attended by many pitiful sights. Aged women, crippled men, lean and haggard invalids with just strength enough to reach the water's edge; poor, shivering, starving wretches who have spent their last farthing to reach this place, exhausted with fatigue, perishing from hunger or disease, struggle to reach the water before their breath shall fail. Here and there in the crowd appear all forms of affliction–hideous lepers and other victims of cancerous and ulcerous diseases, with the noses, lips, fingers and feet eaten away; paralytics in all stages of the disease, people whose limbs are twisted with rheumatism, men and women covered with all kinds of sores, fanatical ascetics with their hair matted with mud and their bodies smeared with ashes, ragged tramps, blind and deformed beggars, women leading children or carrying infants in their arms, handsome rajahs, important officials attended by their servants and chaplains, richly dressed women with their faces closely veiled, dignified and thoughtful Brahmins followed by their disciples, farmers, laborers bearing the signs of toil, and other classes of human society in every stage of poverty or prosperity. They crowd past each other up and down the banks, bathing in the water, drying themselves upon the piers or floats, filling bottles and brass jars from the sacred stream, kneeling to pray, listening to the preachers and absorbed with the single thought upon which their faith is based.

Such exhibitions of faith can be witnessed nowhere else. It is a daily repetition of the scene described in the New Testament when the afflicted thronged the healing pool.

After dipping themselves in the water again and again, combing their hair and drying it, removing their drenched robes–all in the open air–and putting on holiday garments, the pilgrims crowd around the priests who sit at the different shrines, and secure from them certificates showing that they have performed their duty to the gods. The Brahmins give each a text or a name of a god to remember and repeat daily during the rest of his or her life, and they pass on to the notaries who seal and stamp the bottles of sacred water, sell idols, amulets, maps of heaven, charts showing the true way of salvation, certificates of purification, remedies for various diseases, and charms to protect cattle and to make crops grow. Then they pass on to other Brahmins, who paint the sign of their god upon their forehead, the frontal mark which every pilgrim wears. Afterward they visit one temple after another until they complete the pilgrimage at the Golden Temple of Siva, where they make offerings of money, scatter barley upon the ground and drop handfuls of rice and grain into big stone receptacles from which the beggars who hang around the temples receive a daily allowance. Finally they go to the priests of the witness-bearing god, Ganasha, where the pilgrimage is attested and recorded. Then they buy a few more idols, images of their favorite gods, and return to their homes with a tale that will be told around the fireside in some remote village during the rest of their lives.

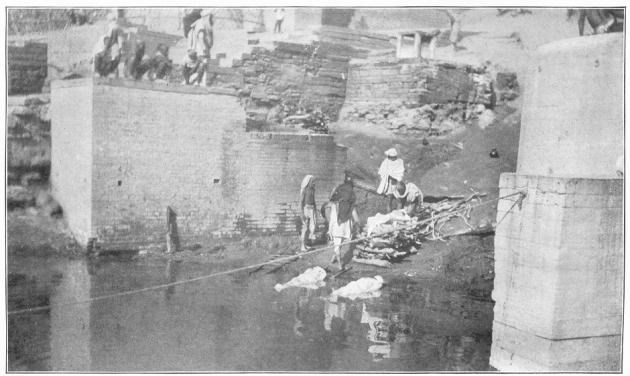

BODIES READY FOR BURNING–BENARES

But the most weird and impressive spectacle at Benares, and one which will never be forgotten, is the burning of the bodies of the dead. At intervals, between the temples along the river bank, are level places belonging to the several castes and leased to associations or individuals who have huge piles of wood in the background and attend to the business in a heartless, mercenary way. The cost of burning a body depends upon the amount and kind of fuel used. The lowest possible rate is three rupees or about one dollar in our money. When the family cannot afford that they simply throw the body into the sacred stream and let it float down until the fish devour it. When a person dies the manager of the burning ghat is notified. He sends to the house his assistants or employes, who bring the body down to the river bank, sometimes attended by members of the family, sometimes without witnesses. It is not inclosed in a coffin, but lies upon a bamboo litter, and under ordinary circumstances is covered with a sheet, but when the family is rich it is wrapped in the richest of silks and embroideries, and the coverlet is an expensive Cashmere shawl.

Arriving at the river an oblong pile of wood is built up and the body is placed upon it. If the family is poor the pile is low, short and narrow, and the limbs of the corpse have to be bent so that they will not extend over the edges, as they often do. When the body arrives it is taken down into the water and laid in a shallow place, where it can soak until the pyre is prepared. Usually the undertakers or friends remove the coverings from the face and splash it liberally from the sacred stream. When the pyre is ready they lift the body from the litter, adjust it carefully, pile on wood until it is entirely concealed, then thrust a few kindlings underneath and start the blaze. When the cremation is complete the charred sticks are picked up by the beggars and other poor people who are always hanging around and claim this waste as their perquisite. The ashes are then gathered up and thrown upon the stream and the current of the Ganges carries them away.

Certain contractors have the right to search the ground upon which the burning has taken place and the shallow river bed for valuables that escaped the flames. It is customary to adorn the dead with the favorite ornaments they wore when alive, and while the gold will melt and diamonds may turn to carbon, jewels often escape combustion, and these contractors are believed to do a good business.

All this burning takes place in public in the open air, and sometimes fifty, sixty or a hundred fires are blazing at the same moment. You can sit upon the deck of your boat with your kodak in your hand, take it all in and preserve the grewsome scene for future reminiscencing.

While the faith of many make them whole, while remarkable cures are occurring at Benares daily, while the sick and the afflicted have assured relief from every ill and trouble, mental, moral and physical, if they can only reach the water's edge, nevertheless scattered about among the temples, squatting behind pieces of bamboo matting or lacquered trays upon which rows of bottles stand, are native doctors who sell all sorts of nostrums and cure-alls that can possibly be needed by the human family, and each dose is accompanied by a guarantee that it will surely cure. These fellows are ignorant impostors and the municipal authorities are careful to see that their drugs are harmless, while they make no attempt to prevent them from swindling the people. It seems to be a profitable trade, notwithstanding the popular faith in the miraculous powers of the river.

Another class of prosperous humbugs is the fortune-tellers, who are found around every temple and in every public place, ready to forecast the fate of every enterprise that may be disclosed to them; ready to predict good fortune and evil fortune, and sometimes they display remarkable penetration and predict events with startling accuracy.

Benares is as sacred to the Buddhists as it is to the Brahmins, for it was here that Gautama, afterward called Buddha (a title which means "The Enlightened"), lived in the sixth century before Christ, and from here he sent out his missionaries to convert the world. Gautama was a prince of the Sakya tribe, and of the Rajput caste. He was born 620 B. C. and lived in great wealth and luxury. Driving in his pleasure grounds one day he met a man crippled with age; then a second man smitten with an incurable disease; then a corpse, and finally a fakir or ascetic, walking in a calm, dignified, serene manner. These spectacles set him thinking, and after long reflection he decided to surrender his wealth, to relinquish his happiness, and devote himself to the reformation of his people. He left his home, his wife, a child that had just been born to him, cut off his long hair, shaved his head, clothed himself with rags, and taking nothing with him but a brass bowl from which he could eat his food, and a cup from which he could drink, he became a pilgrim, an inquirer after Truth and Light. Having discovered that he could drink from the hollow of his hand, he gave away his cup and kept nothing but his bowl. That is the reason why every pilgrim and every fakir, every monk and priest in India carries a brass bowl, for although Buddhism is practically extinct in that country, the teachings and the example of Gautama had a perpetual influence over the Hindus.

After what is called the Great Renunciation, Gautama spent six years mortifying the body and gradually reduced his food to one grain of rice a day. But this brought him neither light nor peace of mind. He thereupon abandoned further penance and devoted six years to meditation, sitting under the now famous bo-tree, near the modern town of Gaya. In the year 588 B. C. he obtained Complete Enlightenment, and devoted the rest of his life to the instruction of his disciples. He taught that all suffering is caused by indulging the desires; that the only hope of relief lies in the suppression of desire, and impressed his principles upon more millions of believers than those of any other religion. It is the boast of the Buddhists that no life was ever sacrificed; that no blood was ever shed; that no suffering was ever caused by the propagation of that faith and the conversion of the world.

After he became "enlightened," Gautama assumed the name of Buddha and went to Benares, where he taught and preached, and had a monastery at the town called Sarnath, now extinct, in the suburbs. There, surrounded by heaps of ruins and rubbish, stand two great topes or towers, the larger of which marks the spot where Buddha preached his first sermon. It is supposed to have been built in the sixth century of the Chinese era, for Hiouen Thsang, a Chinese traveler who visited Sarnath in the seventh century, describes the tower and monastery which was situated near it. It is one of the most interesting as it is one of the most ancient monuments in India, but we do not quite understand the purpose for which it was erected. It is 110 feet high, 93 feet in diameter, and built of solid masonry with the exception of a small chamber in the center and a narrow shaft or chimney running up to the top. The lower half is composed of immense blocks of stone clamped together with iron, and at intervals the monument was encircled by bands of sculptured relief fifteen feet wide. The upper part was of brick, which is now in an advanced state of decay and covered with a heavy crop of grass and bushes. A large tree grows from the top.

There used to be an enormous monastery in the neighborhood, of which the ruins remain. The cells and chapels were arranged around a square court similar to the cloisters of modern monasteries. A half mile distant is another tower and the ruins of other monasteries, and every inch of earth in that part of the city is associated with the life and labor of the great apostle of peace and love, whose theology of sweetness and light and gentleness was in startling contrast with the atrocious doctrines taught by the Brahmins and the hideous rites practiced at the shrines of the Hindu gods. But these towers are not the oldest relics of Buddha. At Gaya, where he received the "enlightenment," the actual birthplace of Buddhism, is a temple built in the year 500 A. D., and it stands upon the site of one that was 700 or 800 years older.

Benares is distinctly the city of Siva, but several thousand other gods are worshiped there, including his several wives. Uma is his first wife, and she is the exact counterpart of her husband; Sati is his most devoted wife; Karali is his most horrible wife; Devi, another of his wives, is the goddess of death; Kali is the goddess of misfortune, and there are half a dozen other ladies of his household whose business seems to be to terrorize and distress their worshipers. But that is the ruling feature of the Hindu religion. There is no sweetness or light in its theology–it exists to make people unhappy and wretched, and to bring misery, suffering and crime into the world.

The Hindus fear their gods, but do not love them, with perhaps the exception of Vishnu, the second person in the Hindu trinity, while Brahma is the third. These three are the supreme deities in the pantheon, but Brahma is more of an abstract proposition than an actual god. For purposes of worship the Hindus may be divided into two classes–the followers of Siva and the followers of Vishnu. They can be distinguished by the "god marks" or painted signs upon their foreheads. Those who wear red are the adherents of Siva, and the followers of Vishnu wear white. Subordinate to these two great divinities are millions of other gods, and it would take a volume to describe their various functions and attributes.

Vishnu is a much more agreeable god than Siva, the destroyer; he has some human feeling, and his various incarnations are friendly heroes, who do kind acts and treat their worshipers tolerably well.

The "Well of Healing," one of the holiest places in Benares, is dedicated to Vishnu. He dug it himself, making a cavity in the rock. Then, in the absence of water, he filled it with perspiration from his own body. This remarkable assertion seems to be confirmed by the foul odor that arises from the water, which is three feet deep and about the consistency of soup. It looks and smells as if it might have been a sample brought from the Chicago River before the drainage canal was finished. It is fed by an invisible spring, and there is no overflow, because, after bathing in it to wash away their sins, the pilgrims drink several cups of the filthy liquid, which often nauseates them, and it is a miracle that any of them survive.

One of the most curious and picturesque of all the temples is that of the goddess Durga, a fine building usually called the Monkey Temple because of the number of those animals inhabiting the trees around it. They are very tame and cunning and can spot a tourist as far as they can see him. When they see a party of strangers approaching the temple they begin to chatter in the trees and then rush for the courtyard of the temple, where they expect to be fed. It is one of the perquisites of the priests to sell rice and other food for them at prices about ten times more than it is worth, but the tourist has the fun of tossing it to them and making them scramble for it. As Durga is the most terrific of all of Siva's wives, and delights in death, torture, bloodshed and every form of destruction, the Hindus are very much afraid of her and the peace offerings left at this temple are more liberal than at the others, a fact very much appreciated by the priests.