полная версия

полная версияModern India

It is an interesting fact that the monsoon currents which cross the Indian Ocean from South Africa continue on their course through Australia after visiting India, and recent famines in the latter country have coincided with the droughts which caused much injury to stock in the former. Thus it has been demonstrated that both countries depend upon the same conditions for their rainfall, except that human beings suffer in India while only sheep die of hunger in the Australian colonies.

The worst famine ever known in India occurred in 1770, when Governor General Warren Hastings reported that one-third of the inhabitants of Bengal perished from hunger–ten millions out of thirty millions. The streets of Calcutta and other towns were actually blocked up with the bodies of the dead, which were thrown out of doors and windows because there was no means or opportunity to bury them. The empire has been stricken almost as hard during the last ten years. The development of civilization seems to make a little difference, for the famine of 1900-1901 was perhaps second in severity to that of 1770. This, however, was largely due to the fact that the population had not had time to recover from the famine of 1896-97, which was almost as severe, although everything possible was done to relieve distress and prevent the spread of plagues and pestilence that are the natural and unavoidable consequences of insufficient nourishment.

No precautions that sanitary science can suggest have been omitted, yet the weekly reports now show an average of twenty thousand deaths from the bubonic plague alone. The officials explain that that isn't so high a rate as inexperienced people infer, considering that the population is nearly three hundred millions, and they declare it miraculous that it is not larger, because the Hindu portion of the population is packed so densely into insanitary dwellings, because only a small portion of the natives have sufficient nourishment to meet the demands of nature and are constantly exposed to influences that produce and spread disease. The death rate is always very high in India for these reasons. But it seems very small when compared with the awful mortality caused by the frequent famines. The mind almost refuses to accept the figures that are presented; it does not seem possible in the present age, with all our methods for alleviating suffering, that millions of people can actually die of hunger in a land of railroads and steamships and other facilities for the transportation of food. It seems beyond comprehension, yet the official returns justify the acceptance of the maximum figures reported.

The loss of human life from starvation in British India alone during the famine of 1900-1901 is estimated at 1,236,855, and this is declared to be the minimum. In a country of the area of India, inhabited by a superstitious, secretive and ignorant population, it is impossible to compel the natives to report accidents and deaths, particularly among the Brahmins, who burn instead of bury their dead. Those who know best assert that at least 15 per cent of the deaths are not reported in times of famines and epidemics. And the enormous estimate I have given does not include any of the native states, which have one-third of the area and one-fourth of the population of the empire. In some of them sanitary regulations are observed, and statistics are accurately reported. In others no attempt is made to keep a registry of deaths, and there are no means of ascertaining the mortality, particularly in times of excitement. In these little principalities the peasants have, comparatively speaking, no medical attendance; they are dependent upon ignorant fakirs and sorcerers, and they die off like flies, without even leaving a record of their disappearance. Therefore the only way of ascertaining the mortality of those sections is to make deductions from the returns of the census, which is taken with more or less accuracy every ten years.

AN EKKA OR ROAD CART

The census of 1901 tells a terrible tale of human suffering and death during the previous decade, which was marked by two famines and several epidemics of cholera, smallpox and other contagious diseases. Taking the whole of India together, the returns show that during the ten years from 1892 to 1901, inclusive, there was an increase of less than 6,000,000 instead of the normal increase of 19,000,000, which was to be expected, judging by the records of the previous decades of the country. More than 10,000,000 people disappeared in the native states alone without leaving a trace behind them.

The official report of the home secretary shows that Baroda State lost 460,000, or 19.23 per cent of its population.

The Rajputana states lost 2,175,000, or 18.1 per cent of their population.

The central states lost 1,817,000, or 17.5 per cent.

Bombay Province lost 1,168,000, or 14.5 per cent.

The central provinces lost 939,000, or 8.71 per cent.

These are the provinces that suffered most from the famine, and therefore show the largest decrease in population.

The famine of 1900-01 affected an area of more than four hundred thousand square miles and a population exceeding sixty millions, of whom twenty-five millions belong in the provinces of British India and thirty-five millions to the native states.

"Within this area," Lord Curzon says, "the famine conditions for the greater part of a year were intense. Outside it they extended with a gradually dwindling radius over wide districts which suffered much from loss of crops and cattle, if not from actual scarcity. In a greater or less degree in 1900-01 nearly one-fourth of the entire population of the Indian continent came within the range of relief operations.

"It is difficult to express in figures with any close degree of accuracy the loss occasioned by so widespread and severe a visitation. But it may be roughly put in this way: The annual agricultural product of India averages in value between two and three hundred thousand pounds sterling. On a very cautious estimate the production in 1899-1900 must have been at least one-quarter if not one-third below the average. At normal prices this loss was at least fifty million pounds sterling, or, in round numbers, two hundred and fifty million dollars in American money. But, in reality, the loss fell on a portion only of the continent, and ranged from total failure of crops in certain sections to a loss of 20 and 30 per cent of the normal crops in districts which are not reckoned as falling within the famine tract. If to this be added the value of several millions of cattle and other live stock, some conception may be formed of the destruction of property which that great drought occasioned. There have been many great droughts in India, but there have been no others of which such figures could have been predicated as these.

"But the most notable feature of the famine of 1900-01 was the liberality of the public and the government. It has no parallel in the history of the world. For weeks more than six million persons were dependent upon the charity of the government. In 1897 the high water mark of relief was reached in the second fortnight of May, when there were nearly four million persons receiving relief in British India. Taking the affected population as forty millions, the ratio of relief was 10 per cent. In one district of Madras and in two districts of the northwestern provinces the ratio for some months was about 30 per cent, but these were exceptional cases. In the most distressed districts of the central provinces 16 per cent was regarded in 1896-7 as a very high standard of relief. Now take the figures of 1900-01. For some weeks upward of four and a half million persons were receiving food from the government in British India, and, reckoned on a population of twenty-five millions, the ratio was 18 per cent, as compared with 10 per cent of the population in 1897. In many districts it exceeded 20 per cent. In several it exceeded 30 per cent. In two districts it exceeded 40 per cent, and in the district of Merwara, where famine had been present for two years, 75 per cent of the population were dependent upon the government for food. Nothing I could say can intensify the simple eloquence of these figures.

"The first thing to be done was to relieve the immediate distress, to feed the hungry, to rescue those who were dying of starvation. The next step was to furnish employment at living wages for those who were penniless until we could help them to get upon their feet again, and finally to devise means and methods to meet such emergencies in the future, because famines are the fate of India and must continue to recur under existing conditions.

"I should like to tell you of the courage, endurance and the devotion of the men who distributed the relief, many of whom died at their posts of duty as bravely and as uncomplainingly as they might have died upon the field of battle. The world will never know the extent and the number of sacrifices made by British and native officials. The government alone expended $32,000,000 for food, while the amount disbursed by the native states, by religious and private charities, was very large. The contributions from abroad were about $3,000,000, and the government loaned the farmers more than $20,000,000 to buy seed and cattle and put in new crops.

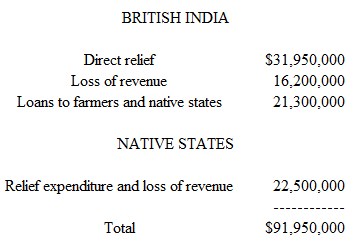

"So far as the official figures are concerned, the total cost of the famine of 1900 was as follows:

"Some part of these loans and advances will eventually be repaid. But it is not a new thing for the government of India to relieve its people in times of distress. The frequent famines have been an enormous drain upon the resources of the empire."

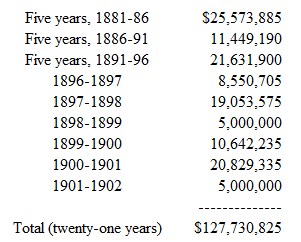

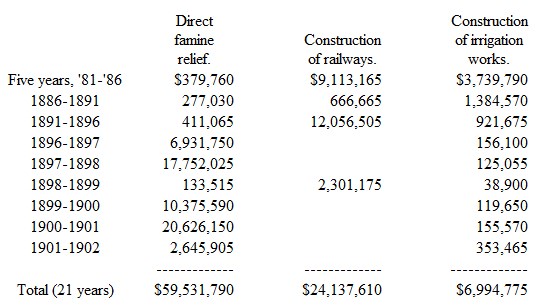

The following table shows the expenditures for famine relief by the imperial government of India during the last twenty-one years:

Among the principal items chargeable to famine relief, direct and indirect, are the wages paid dependent persons employed during famines in the construction of railways and irrigation works, which, during the last twenty-one years, have been as follows:

The chief remedies which the government has been endeavoring to apply are:

1. To extend the cultivated area by building irrigation works and scattering the people over territory that is not now occupied.

2. To construct railways and other transportation facilities for the distribution of food. This work has been pushed with great energy, and during the last ten years the railway mileage has been increased nearly 50 per cent to a total of more than 26,000 miles. About 2,000 miles are now under construction and approaching completion, and fresh projects will be taken up and pushed so that food may be distributed throughout the empire as rapidly as possible in time of emergency. Railway construction has also been one of the chief methods of relief. During the recent famine, and that of 1897, millions of coolies, who could find no other employment, were engaged at living wages upon various public works. This was considered better than giving them direct relief, which was avoided as far as possible so that they should not acquire the habit of depending upon charity. And as a part of the permanent famine relief system for future emergencies, the board of public works has laid out a scheme of roads and the department of agriculture a system of irrigation upon which the unemployed labor can be mobilized at short notice, and funds have been set apart for the payment of their wages. This is one of the most comprehensive schemes of charity ever conceived, and must commend to every mind the wisdom, foresight and benevolence of the Indian government, which, with the experience with a dozen famines, has found that its greatest difficulty has been to relieve the distressed and feed the hungry without making permanent paupers of them. Every feature of famine relief nowadays involves the employment of the needy and rejects the free distribution of food.

3. The government is doing everything possible to encourage the diversification of labor, to draw people from the farms and employ them in other industries. This requires a great deal of time, because it depends upon private enterprise, but during the last ten years there has been a notable increase in the number of mechanical industries and the number of people employed by them, which it is believed will continue because of the profits that have been realized by investors.

4. The government is also making special efforts to develop the dormant resources of the empire. There has been a notable increase in mining, lumbering, fishing, and other outside industries which have not received the attention they deserved by the people of India; and, finally,

5. The influence of the government has also been exerted so far as could be to the encouragement of habits of thrift among the people by the establishment of postal savings banks and other inducements for wage-earners to save their money. Ninety per cent of the population of India lives from hand to mouth and depends for sustenance upon the crops raised upon little patches of ground which in America would be too insignificant for consideration. There is very seldom a surplus. The ordinary Hindu never gets ahead, and, therefore, when his little crop fails he is helpless.

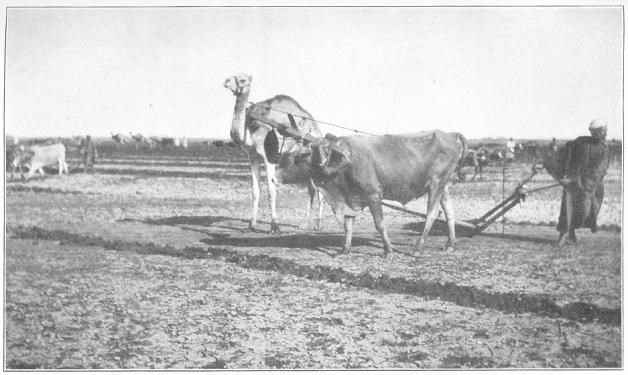

A TEAM OF "CRITTERS"

The munificence of Mr. Henry Phipps of New York has enabled the government of India to provide one of the preventives of famine by educating the people in agricultural science. A college, an experimental farm and research laboratory have been established on the government estate of Pusa, in southern Bengal, a tract of 1,280 acres, which has been used since 1874 as a breeding ranch, a tobacco experimental farm and a model dairy. No country has needed such an institution more than India, where 80 per cent of the population are engaged in agricultural pursuits, and most of them with primitive implements and methods. But the conservatism and the illiteracy, the prejudices and the ignorance of the natives make it exceedingly difficult to introduce innovations, and it is the conviction of those best qualified to speak that the only way of improving the condition of the farmer classes is to begin at the top and work down by the force of example. During a recent visit to India this became apparent to Mr. Phipps, who is eminently a practical man, and has been in the habit of dealing with industrial questions all of his life. He was brought up in the Carnegie iron mills, became a superintendent, a manager and a partner, and, when the company went into the great trust, retired from active participation in its management with an immense fortune. He has built a beautiful house in New York, has leased an estate in Scotland, where his ancestors came from, and has been spending a vacation, earned by forty years of hard labor, in traveling about the world. His visit to India brought him into a friendly acquaintance with Lord Curzon, in whom he found a congenial spirit, and doubtless the viceroy received from the practical common sense of Mr. Phipps many suggestions that will be valuable to him in the administration of the government, and in the solution of the frequent problems that perplex him. Mr. Phipps, on the other hand, had his sympathy and interest excited in the industrial conditions of India, and particularly in the famine phenomena. He therefore placed at the disposal of Lord Curzon the sum of $100,000, to which he has since added $50,000, to be devoted to whatever object of public utility in the direction of scientific research the viceroy might consider most useful and expedient. In accepting this generous offer it appeared to His Excellency that no more practical or useful object could be found to which to devote the gift, nor one more entirely in harmony with the wishes of the donor, than the establishment of a laboratory for agricultural research, and Mr. Phipps has expressed his warm approval of the decision.

It is proposed to place the college upon a higher grade than has ever been reached by any agricultural school in India, not only to provide for a reform of the agricultural methods of the country, but also to serve as a model for and to raise the standard of the provincial schools, because at none of them are there arrangements for a complete or competent agricultural education. It is proposed to have a course of five years for the training of teachers for other institutions and the specialists needed in the various branches of science connected with the agricultural department, who are now imported from Europe. The necessity for such an education, Lord Curzon says, is constantly becoming more and more imperative. The higher officials of the government have long realized that there should be some institution in India where they can train the men they require, if their scheme of agricultural reformation is ever to be placed upon a practical basis and made an actual success. For those who wish to qualify for professorships or for research work, or for official positions requiring special scientific attainments, it is believed that a five years' course is none too long. But for young men who desire only to train themselves for the management of their own estates or the estates of others, a three years' course will be provided, with practical work upon the farm and in the stable.

The government has solved successfully several of the irrigation problems now under investigation by the Agricultural Department and the Geological Survey of the United States. The most successful public works of that nature are in the northern part of the empire. The facilities for irrigation in India are quite as varied as in the United States, the topography being similar and equally diverse. In the north the water supply comes from the melting snows of the Himalayas; in the east and west from the great river systems of the Ganges and the Indus, while in the central and southern portions the farmers are dependent upon tanks or reservoirs into which the rainfall is drained and kept in store until needed. In several sections the rainfall is so abundant as to afford a supply of water for the tanks which surpluses in constancy and volume that from any of the rivers. In Bombay and Madras provinces almost all of the irrigation systems are dependent upon this method. In the river provinces are many canals which act as distributaries during the spring overflow, carry the water a long distance and distribute it over a large area during the periods of inundation. In several places the usefulness of these canals has been increased by the construction of reservoirs which receive and hold the floods upon the plan proposed for some of our arid states.

In India the water supply is almost entirely controlled by the government. There are some private enterprises, but most of them are for the purpose of reaching land owned by the projectors. A few companies sell water to the adjacent farmers on the same plan as that prevailing in California, Colorado and other of our states. But the government of India has demonstrated the wisdom of national ownership and control, and derives a large and regular revenue therefrom. In the classification adopted by the department of public works the undertakings are designated as "major" and "minor" classes. The "major" class includes all extensive works which have been built by government money, and are maintained under government supervision. Some of them, classed as "famine protective works," were constructed with relief funds during seasons of famine in order to furnish work and wages to the unemployed, and at the same time provide a certain supply of water for sections of the country exposed to drought. The "minor" works are of less extent, and have been constructed from time to time to assist private enterprise.

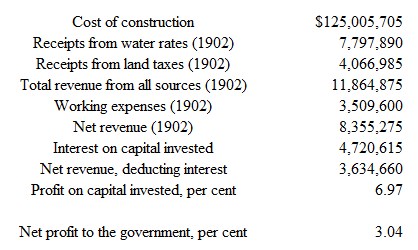

The financial history of the public irrigation works of India will be particularly interesting to the people of the United States because our government is just entering upon a similar policy, the following statement is brought down to December 31, 1902:

In addition to this revenue from the "major" irrigation works belonging to the government, the net receipts from "minor" works during the year 1902 amounted to $864,360 in American money.

In other words, the government of India has invested about $125,000,000 in reservoirs, canals, dams and ditches for the purpose of securing regular crops for the farmers of that empire who are exposed to drought, and not only has accomplished that purpose, but, after deducting 3-1/2 per cent as interest upon the amount named, enjoys a net profit of more than $3,500,000 after the payment of running expenses and repairs. These profits are regularly expended in the extension of irrigation works.

In the Sinde province, which is the extreme western section of India, adjoining the colony of Beluchistan on the Arabian Sea, there are about 12,500,000 acres of land fit for cultivation. Of this a little more than 9,000,000 acres are under cultivation, irrigated with water from the Indus River, and the government system reaches 3,077,466 acres. Up to December 31, 1902, it had expended $8,830,000 in construction and repairs, and during that year received a net revenue of 8.5 per cent upon that amount over and above interest and running expenses.

In Madras 6,884,554 acres have peen irrigated by the government works at a cost of $24,975,000. In 1902 they paid an average net revenue of 9.5 per cent upon the investment, and the value of the crops grown upon the irrigated land was $36,663,000.

In the united provinces of Agra and Oudh in northern India the supply of water from the Himalayas is distributed through 12,919 miles of canals belonging to the government, constructed at a cost of $28,625,000, which irrigates 2,741,460 acres. In 1902 the value of the crops harvested upon this land was $28,336,005, and the government received a net return of 6.15 per cent upon the investment. The revenue varies in different parts of the provinces. One system known as the Eastern Jumna Canal, near Lucknow, paid 23 per cent upon its cost in water rents during that year. In other parts of the province, where the construction was much more expensive, the receipts fell as low as 2.12 per cent.

In the Punjab province, the extreme northwestern corner of India, adjoining Afghanistan on the west and Cashmere on the east, where the water supply comes from the melting snows of the Himalayas, the government receives a net profit of 10.83 per cent, and the value of the crop in the single year of 1902 was one and one-fourth times the total amount invested in the works to date.

This does not include a vast undertaking known as the Chenab Canal, which has recently been completed, and now supplies more than 2,000,000 acres with water. Its possibilities include 5,527,000 acres. As a combination of business and benevolence and as an exhibition of administrative energy and wisdom, it is remarkable, and is of especial interest to the people of the United States because the conditions are similar to those existing in our own arid states and territories.

If you will take a map of India and run your eye up to the northwestern corner you will see a large bald spot just south of the frontier through which runs the river Chenab (or Chenaub)–the name of the stream is spelt a dozen different ways, like every other geographical name in India. This river, which is a roaring torrent during the rainy season and as dry as a bone for six months in the year, resembles several of out western rivers, particularly the North Platte, and runs through an immense tract of arid desert similar to those found in our mountain states. This desert is known as the Rechna Doab, and until recently was waste government land, a barren, lifeless tract upon which nothing but snakes and lizards could exist, although the soil is heavily charged with chemicals of the most nutritious character for plants, and when watered yields enormous crops of wheat and other cereals. Fifteen years ago it was absolutely uninhabited. To-day it is the home of about 800,000 happy and prosperous people, working more than 200,000 farms, in tracts of from five to fifty acres. The average population of the territory disclosed at the census of 1901 was 212 per square mile, and it is expected that the extension of the water supply and natural development will largely increase this average.