полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 492, June 4, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 492, June 4, 1831

THREE BOROUGHS

Proposed to be wholly disfranchised by the REFORM BILL.

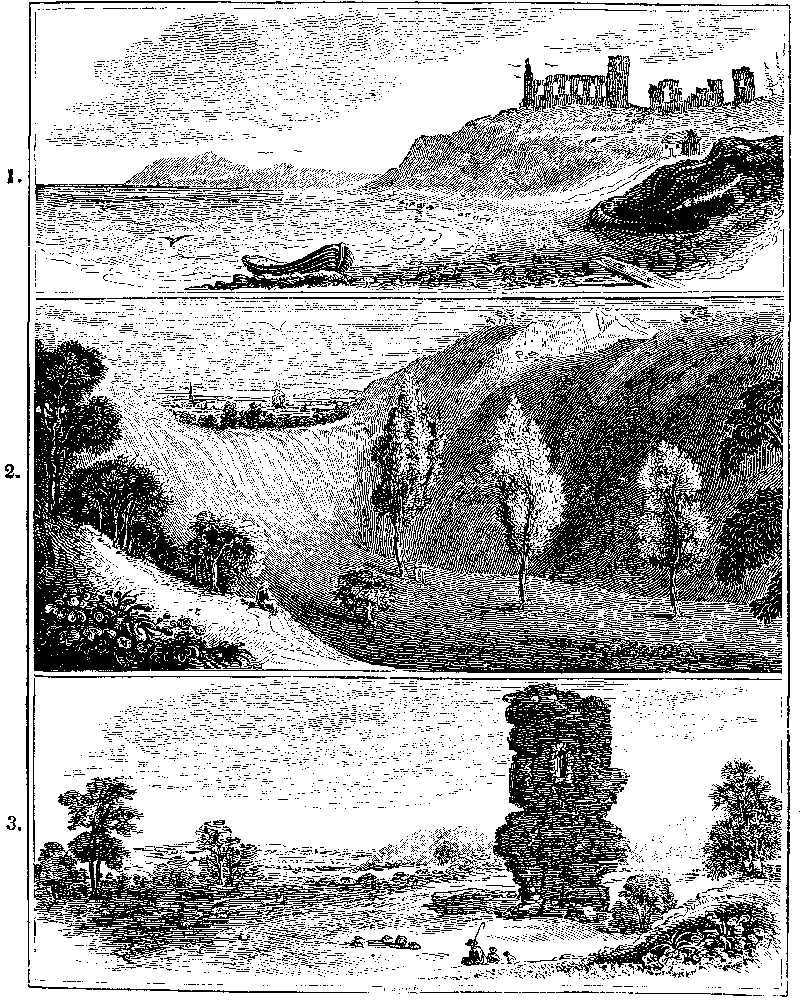

1. DUNWICH. 2. OLD SARUM. 3. BRAMBER.

THREE BOROUGHS:

1. DUNWICH, SUFFOLK.

2. OLD SARUM, WILTS.

3. BRAMBER, SUSSEX.

Proposed to be wholly disfranchised by "the Reform Bill."We feel ourselves on ticklish—debateable ground; yet we only wish to illustrate the topographical history of the above places; their parliamentary history must, however be alluded to; but their future fate we leave to the 658 prime movers of government mechanics. Mr. Oldfield's History of the Boroughs, the best companion of the member of parliament, shall aid us: instead of companion we might, however, call this work his family, for there are six full-grown octavo volumes, which would occupy a respectable portion of any library table.

Dunwich is a market town in the hundred of Blything, Suffolk, three and a half miles from Southwold, and one hundred from London. It was once an important, opulent, and commercial city, but is now a mean village. It was also an episcopal see, but William I. transferred the see to Thetford, and thence to Norwich. Dunwich stands on a cliff of considerable height commanding an extensive view of the German Ocean, and we learn that its ruin is owing chiefly to the encroachments of the sea. It is a poor, desolate place, as the cut implies. Mr. Shoberl, in the Beauties of England and Wales, tells us "seated upon a hill composed of loam and sand of a loose texture, on a coast destitute of rocks, it is not surprising that its building shall have successively yielded to the impetuosity of the billows, breaking against, and easily undermining the foot of the precipice." Certainly not, say we; and it is equally un-surprising that seven out of its eight parishes having been long ago destroyed, their political consequence should not exist beyond their extermination. Mr. Oldfield, whom we remember to have often met, was a man of jocose turn, and he has not spared Dunwich his whip of humour, for, speaking of its gradual decay by the sea, he says—"the encroachment that is still making, (1816) will probably, in a few years, oblige the constituent body to betake themselves to a boat, whenever the king's writ shall summon them to the exercise of their elective functions; as the necessity of adhering to forms, in the farcical solemnity of borough elections, is not to be dispensed with."

We must be brief with its representative and political history. "Out brief candle!" It has sent members since the 23rd Edward I. Bribery and other irregularities against the sitting members in procuring votes were proved in 1696: in 1708, Sir Charles Bloyce, one of the bailiffs was returned, but upon a petition proving bribery, menaces, treating, &c. this was proved to be "no return:" Sir Charles was declared not capable of being elected, "as being one of the bailiffs; nor had the other bailiff alone any authority to make a return, the two bailiffs making but one officer."1 In 1722 another bribery petition was presented, but the affair was made up, and the complaint withdrawn. After this display of venality, it is amusing to read that the corporation consists of two bailiffs and twelve capital burgesses.2

Mr. Oldfield described this borough fourteen years ago, as consisting of only forty-two houses, and half a church, the other part having been demolished. Here were six if not eight parish churches: namely, St. John's, (which was a rectory, and seems to have been swallowed up by the sea about the year 1540;) St. Martin's, St. Nicholas's, and St. Peter's, which were likewise rectories; and St. Leonard's and All Saints, which were impropriated. The register of Eye also mentions the churches of St. Michael and St. Bartholomew, which were swallowed up by the sea before the year 1331. The ocean here appears to have almost a corporation swallow. The walls, which encompassed upwards of seven acres of land, had three gates. That to the eastward is quite demolished; but the arches of the two gates to the westward continue pretty firm, and are of curious workmanship, which nature has almost covered with ivy.

By aid of the excellent parliamentary anatomy, in the Spectator newspaper, we learn that DUNWICH, according to the census of 1821, contained 200 persons.

The "patrons," or "prevailing influence," are Mr. M. Barne and Lord Huntingfield. The number of votes is 18.

The members "returned" to the last parliament were F. Barne and the Earl of Brecknock, who were also returned at the recent election.

Old Sarum, Wilts, the second Borough, has been already fully illustrated in vol. x., No. 290, of The Mirror. It fell, or was rather pulled down, in consequence of a squabble between the civil and ecclesiastical authorities; and soon after 1217, the inhabitants removed the city, by piecemeal, to another site, which they called New Sarum, now Salisbury. The site of the old city was very recently a field of oats; and the remains of its cathedral, castle, &c., were heaps of rubbish, covered with unprofitable verdure. We may therefore say,

Ubi seges, Sarum fuit.Mr. Britton, in the Beauties of England and Wales, discourses diligently of its antiquarian history, which we have glanced at in our tenth volume. It is in the parish of Stratford-under-the-Castle; and under an old tree, near the church, is the spot where the members for Old Sarum are elected, or rather deputed, to sit in parliament. The father of the great Earl of Chatham once resided at an old family mansion in this parish; and the latter was first sent to parliament from the borough of Old Sarum, in February, 1735; yet "the great Earl Chatham called these boroughs the excrescences, the rotten part of the constitution, which must be amputated to save the body from a mortification."—(Oldfield.)

Few particulars of its representative history are worth relating. The borough returned members to Parliament 23rd Edward I., and then intermitted till 34th Edward III., since which time it has constantly returned. By the return 1 Henry V. it appears that its representatives were with those of other boroughs elected at the county court.

Old Sarum was the property of the late Lord Camelford, who sold it to the Earl of Caledon. The suffrage is by burgage-tenure. The voters, seven, are nominated by the proprietor; but (says Oldfield) actually only one.

The population of Old Sarum is included in the parish, and is not distinguished in its returns.

The proprietor is Lord Caledon; and the members in the last parliament were J.J. and J.D. Alexander, who were again returned at the recent election.

The Cut is an accurate view of the old borough, with Salisbury Cathedral in the distance.

Bramber is here represented by the forlorn ruins of its Castle. It is in the hundred of Steyning, rape of Bramber, Sussex, and is half a mile from Steyning. It sent members as early as the two previous boroughs; it afterwards intermitted sending, and sometimes sent in conjunction with Steyning, before the 7th Edward IV. There is much "tampering" in its representative records: in 1700, one Mr. Samuel Shepherd was charged with these matters here, and in Wiltshire and Hampshire, when he was ordered to the Tower of London; but a week afterwards, Mr. Shepherd was declared to have absconded. In 1706, a Mr. Asgill, one of the Bramber members, was delivered out of the Fleet by his parliamentary privilege, and the aid of the Sergeant-at-Arms and his mace; but in the following month he was expelled the house for his writings.

The right of election is in resident burgage-holders; and the number of voters is stated to be twenty. The place consists of a few miserable thatched cottages. The Duke of Norfolk is lord of the manor. The cottages are one half of them the property of the Duke of Rutland, and the other of Lord Calthorpe, who, since the year 1786, have each agreed to send one member.3

The history of the Castle seen in the Cut merits note, especially as it is the only relic of the former consequence of the place. It was the baronial castle of the honour of Bramber, which, at the time of the Conqueror's survey, belonged to William de Braose, who possessed forty other manors in this county. These were held by his descendants for several generations by the service of the knights' fees; and they obtained permission to build themselves a castle here; but the exact date of its erection is not known. Its ruins attest that it was once a strong and extensive edifice. It appears to have completely covered the top of a rugged eminence, which commands a fine view of the adjacent country and the sea, and to have been surrounded by a triple trench. The population of Bramber is in the Returns of 1821—ninety-eight persons. The members in the last parliament were the Honourable F.G. Calthorpe and John Irving; at the recent election, the members returned were J. Irving and W.S. Dugdale.

Such is an outline of the histories of the annexed three Boroughs. Two of them are sites of great beauty; and we leave the reader to reflect on these pleasant features in association with their rise, decline, and we opine, political extermination.

MANNERS & CUSTOMS OF ALL NATIONS

ORIGIN OF THE COBBLER'S ARMS

Charles V., in his intervals of relaxation, used to retire to Brussels. He was a prince curious to know the sentiments of his meanest subjects, concerning himself and his administration; he therefore often went out incog. and mixed in such companies and conversations as he thought proper. One night his boot required immediate mending; he was directed to a cobbler not inclined for work, who was in the height of his jollity among his acquaintance. The emperor acquainted him with what he wanted, and offered a handsome remuneration for his trouble.

"What, friend," says the fellow, "do you know no better than to ask any of our craft to work on St. Crispin? Was it Charles the Fifth himself, I'd not do a stitch for him now; but if you'll come in and drink St. Crispin, do, and welcome—we are merry as the emperor can be."

The sovereign accepted his offer; but while he was contemplating on their rude pleasure, instead of joining in it, the jovial host thus accosts him:

"What, I suppose you are some courtier politician or other, by that contemplative phiz!—nay, by your long nose, you may be a bastard of the emperor's; but, be who or what you will, you're heartily welcome. Drink about; here's Charles the Fifth's health."

"Then you love Charles the Fifth?" replied the emperor.

"Love him!" says the son of Crispin, "ay, ay, I love his long-noseship well enough; but I should love him much more, would he but tax us a little less. But what the devil have we to do with politics! Round with the glass, and merry be our hearts!"

After a short stay, the emperor took his leave, and thanked the cobbler for his hospitable reception. "That," cried he, "you're welcome to; but I would not to day have dishonoured St. Crispin to have worked for the emperor."

Charles, pleased with the honest good nature and humour of the fellow, sent for him next morning to court. You may imagine his surprise, to see and hear that his late guest was his sovereign: he was afraid his joke on his long nose would be punished with death. The emperor thanked him for his hospitality, and, as a reward for it, bid him ask for what he most desired, and to take the whole night to think of it. The next day he appeared, and requested that for the future the cobblers of Flanders might bear for their arms a boot with the emperor's crown upon it.

That request was granted; and so moderate was his ambition, that the emperor bid him make another. "If," says the cobbler, "I might have my utmost wish, command that for the future the company of cobblers shall take place of the company of shoemakers."

It was accordingly so ordained by the emperor; and to this day there is to be seen a chapel in Brussels adorned round with a boot and imperial crown, and in all processions the company of cobblers take precedence of the company of shoemakers.

G.KSINGULAR TENURE

King John gave several lands, at Kepperton and Atterton, in Kent, to Solomon Attefeld, to be held by this singular service—that as often as the king should be pleased to cross the sea, the said Solomon, or his heirs, should be obliged to go with him, to hold his majesty's head, if there should be occasion for it, "that is, if he should be sea-sick;" and it appears, by the record in the Tower, that this same office of head-holding was actually performed in the reign of Edward the First.

J.R.S"AS BAD AS PLOUGHING WITH DOGS."

(To the Editor.)Famed as your miscellany is for local and provincial terms, customs, and proverbs, I have often wondered never to have met with therein this old comparative north country proverb—"As bad as ploughing with dogs;" which evidently originated from the Farm-house; for when ploughmen (through necessity) have a new or awkward horse taken into their team, by which they are hindered and hampered, they frequently observe, "This is as bad as ploughing with dogs." This proverb is in the country so common, that it is applied to anything difficult or abstruse: even at a rubber at whist, I have heard the minor party execrate the business in these words, "It is as bad as ploughing with dogs," give it up for lost, change chairs, cut for partners, and begin a new game.

H.B.ACROESUS.—A DRAMATIC SKETCH

(For the Mirror.)Cyrus, Courtiers, and Officers of State. Croesus bound upon the funeral pile which is guarded by Persian soldiers, several of them bearing lighted torches, which they are about to apply to the pile.

Croesus.—O, Solon, Solon, Solon.Cyrus.—Whom calls he on?Attendant.—Solon, the sage.Croesus.—How true thy wordsNo man is happy till he knows his end.Cyrus.—Can Solon help thee?Croesus.—He hath taught me thatWhich it were well for kings to know.Cyrus.—Unbind him—we would hear it.Croesus.—The fame of Solon having spread o'er Greece,We sent for him to Sardis. Robed in purple,We and our court received him: costly gemsBedecked us—glittering in golden beds,We told him of our riches. He was moved not.We showed him our vast palace, hall, and chamber,Cellar and attic not omitting—Statues and urns, and tapestry of gold,Carpets and furniture, and Grecian paintings,Diamonds and sapphires, rubies, emeralds,And pearls, that would have dazzled eagles' sight.Lastly, our treasury!—we showed him Lydia's wealth!And then exulting, asked him, whom of all menThat in the course of his long travels he had seenHe thought most happy?—He replied,"One Tellus, an Athenian citizen,Of little fortune, and of less ambition,Who lived in ignorance of penury,And ever saw his country flourish;His children were esteemed—he lived to seeHis children's children—then he fell in battle,A patriot, a hero, and a martyr!"Whom next?—I asked, "Two Argive brothers,Whose pious pattern of fraternal loveAnd filial duty and affection,Is worthy of example and remembrance.Their mother was a priestess of the queenOf the supreme and mighty Jupiter!And she besought her goddess to send downThe best of blessings on her duteous sons.Her prayers were heard—they slept and died!"Then you account me not among the happy?To which the sage gave answer—"King of Lydia! Our philosophyIs but ill suited to the courts of kings.We do not glory in our own prosperity,Nor yet admire the happiness of others.All bliss is brief and superficial,And should not be accounted as a good,But that which lasts unto our being's end.The life of man is threescore years and ten,Which being summed in the whole amountUnto some thousands of swift-winged days,Of which there are not two alike;So those which are to come, being unknown,Are but a series of accidents:Therefore esteem we no man happy,But him whose happiness continues to the end!We cannot win the prize until the contest's o'er!."Cyrus.—Solon hath saved one kingAnd taught another! Torchmen, we reprieveThe captive Croesus.CYMBELINEPAUL'S CROSS

(For the Mirror.)"–Friers and faytours have fonden such questionsTo plese with the proud men, sith the pestilence time,4And preachen at St. Paul's, for pure envi fo clarkes,That praiers have no powre the pestilence to lette."Piers Plowman's Visions.The early celebrity of Paul's Cross, as the greatest seat of pulpit eloquence, is evinced in the lines above quoted, which give us to understand that the most subtle and abstract questions in theology were handled here by the Friars, in opposition to the secular clergy, almost at the first settlement of that popular order of preachers in England.

Of the custom of preaching at crosses it is difficult to trace the origin; it was doubtless far more remote than the period alluded to, and Pennant thinks, at first accidental. The sanctity of this species of pillar, he observes, often caused a considerable resort of people to pay their devotion to the great object of their erection. A preacher, seeing a large concourse might be seized by a sudden impulse, ascend the steps, and deliver out his pious advice from a station so fit to inspire attention, and so conveniently formed for the purpose. The example might be followed till the practice became established by custom.

The famous Paul's Cross, like many others in various parts of the kingdom (afterwards converted to the same purpose,) was doubtless at first a mere common cross, and might be coeval with the Church. When it was covered and used as a pulpit cross, we are not informed. Stowe describes it in his time, "as a pulpit-crosse of timber, mounted upon steppes of stone, and covered with leade, standing in the church-yard, the very antiquitie whereof was to him unknowne." We hear of its being in use as early as the year 1259, when Henry III., in person commanded the mayor to swear before him every stripling of twelve years old and upwards, to be true to him and his heirs. Here in 1299, Ralph de Baldoc, dean of St. Paul's, cursed all those who had searched, in the church, of St. Martin in the Fields, for a hoard of gold, &c. Before this cross in 1483, was brought, divested of all her splendour, Jane Shore, the charitable, the merry concubine of Edward IV., and, after his death, of his favourite, the unfortunate Lord Hastings. After the loss of her protectors, she fell a victim to the malice of crook-backed Richard. He was disappointed (by her excellent defence) of convicting her of witchcraft, and confederating with her lover to destroy him. He then attacked her on the weak side of frailty. This was undeniable. He consigned her to the severity of the church: she was carried to the bishop's palace, clothed in a white sheet, with a taper in her hand, and from thence conducted to the cathedral, and the cross, before which she made a confession of her only fault. Every other virtue bloomed in this ill-fated fair with the fullest vigour. She could not resist the solicitations of a youthful monarch, the handsomest man of his time. On his death she was reduced to necessity, scorned by the world, and cast off by her husband, with whom she was paired in her childish years, and forced to fling herself into the arms of Hastings. "In her penance she went," says Holinshed "in countenance and pase demure, so womanlie, that, albeit she were out of all araie, save her kirtle onlie, yet went she so faire and lovelie, namelie, while the woondering of the people cast a comlie rud in hir cheeks, (of which she before had most misse) that hir great shame won hir much praise among those that were more amorous of hir bodie than curious of hir soule." She lived to a great age, but in great distress and miserable poverty; deserted even by those to whom she had, during prosperity, done the most essential services.

From this time the Cross continually occurs in history. "It was used not only for the instruction of mankind by the doctrine of the preacher, but for every purpose, political or ecclesiastical; for giving force to oaths; for promulgating of laws, or rather the royal pleasure; for royal contracts of marriage; for the emission of papal bulls; for anathematizing sinners; for benedictions; for exposing of penitents under the censure of the church; for recantations; for the private ends of the ambitious; and for the defaming of those who had incurred the displeasure of crowned heads."

Bishop King preached the last sermon here, of any note, before James I., and his court on Midlent Sunday, 1620. The object of the sermon was the repairing of the cathedral; and the ceremony was conducted with so much magnificence, that the prelate exclaims, in a part of his sermon,—"But will it almost be believed, that a King should come from his court to this crosse, where princes seldom or never come, and that comming to bee in a state, with a kinde of sacred pompe and procession, accompanied with all the faire flowers of his field, and the fairest rose (the Queen) of his owne garden!" The cross was demolished by order of Parliament in 1643, executed by the willing hands of Isaac Pennington, the fanatical Lord Mayor of that year, who died a convicted regicide in the Tower. It stood at the north-east end of St. Paul's Churchyard; a print of the cross, and likewise the shrouds, where the company sat in wet weather, may be seen in Speed's Theatre of Great Britain.

J.R.SADA

(For the Mirror.)She stood in the midst of that gorgeous throng,Her praise was the theme of every tongue;Warriors were there, whose glance of fireSpoke to their foes of vengeance dire,But they were enslaved by beauty's power,And knelt at her shrine in that moonlit bower.Sweet words were breathed in Ada's earBy many a noble cavalier;Maidens with fairy steps were there,Who seemed to float on the ambient air,But none in the mazy dance could moveLike Ada, the queen of this bower of love!The moon in her silvery beauty shinesOn this joyous throng through the lofty pines;Lamps gleaming forth from every tree,All was splendour and revelry;Sweet perfumes were wafted by every breezeFrom the flowering shrubs and the orange trees,Mingling with sounds which were borne alongFrom the lover's lute and the minstrel's song;Fair Ada's praise was the theme of all,She was the queen of this festival.She left the crowd and wandered on—Where, oh where is the maiden gone?She hears no longer the minstrel's lay,The last sweet notes have died away,Like the low, faint sound of maiden's sigh.When the youth that she loves is standing by.But where, oh where is Ada gone?She is kneeling in a dungeon lone;Her fillet of snowy pearls has nowFall'n from its throne on her whiter brow,And her fair, rich tresses, like floods of gold,Gleam on the floor so damp and cold.Her cheek is pale, but her eye of blueNow wears a bright and more glorious hue;It tells of a maiden's constancy,Of her faith in the hour of adversity;On a pallet of straw in that gloomy cell,Is a captive knight whom she loves so well,That she's left her joyous and splendid bowerTo dwell with him in his dying hour,To pillow his head on her breast of snow,To kiss the dew from his pallid brow;With smiles to chase the thoughts of gloomWhich darken his way to an early tomb,To shed no tear, and to heave no sigh,Though her heart is breaking in agony.M.A.JSPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

PITCAIRN'S ISLAND

The Quarterly Review (89) last published, is, indeed, a Reform Number; for all the papers, save one, relate to some species of reform or improvement.—Thus, we have papers on Captain Beechey's recent Voyage to co-operate with the Polar Expeditions—Population and Emigration—the notable Conspiration de Babeuf—the West India Question—and last, though not least, "the Bill" itself. We have endeavoured to adopt from the first paper, some particulars of a spot which bears high interest for every lover of adventure; the reviewer's observations connecting the extracts from Captain Beechey's large work.