полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 358, February 28, 1829

There are two places in the interior of Mekka where the aqueduct runs above ground; there the water is let off into small channels or fountains, at which some slaves of the Sherif are stationed, to exact a toll from persons filling their water-skins. In the time of the Hadj, these fountains are surrounded day and night by crowds of people quarrelling and fighting for access to the water. During the late siege, the Wahabys cut off the supply of water from the aqueduct; and it was not till some time after, that the injury which this structure then received, was partially repaired.

There is a small spring which oozes from under the rocks behind the great palace of the Sherif, called Beit el Sad; it is said to afford the best water in this country, but the supply is very scanty. The spring is enclosed, and appropriated wholly to the Sherif's family.

Beggars, and infirm or indigent hadjys, often entreat the passengers in the streets of Mekka for a draught of sweet water; they particularly surround the water-stands, which are seen in every corner, and where, for two paras in the time of the Hadj, and for one para, at other times, as much water may be obtained as will fill a jar.—Burckhardt's Travels in Arabia.

The Naturalist

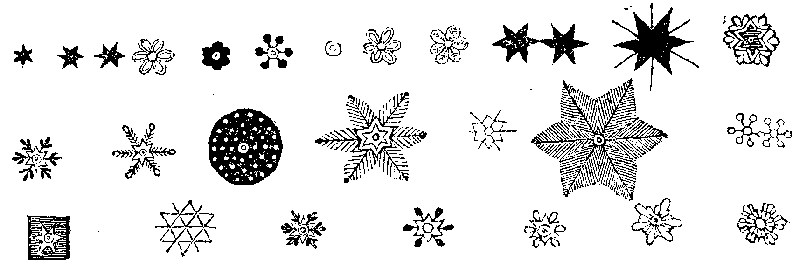

FLAKES OF SNOW MAGNIFIED.

FLAKES OF SNOW MAGNIFIED

Snow is one of the treasures of the atmosphere. Its wonderful construction, and the beautiful regularity of its figures, have been the object of a treatise by Erasmus Bartholine, who published in 1661, "De Figurâ Nivis Dissertatio," with observations of his brother Thomas on the use of snow in medicine. On examining the flakes of snow with a magnifying glass before they melt, (which may easily be done by making the experiment in the open air,) they will appear composed of fine shining spicula or points, diverging like rays from a centre. As the flakes fall down through the atmosphere, they are joined by more of these radiated spicula, and thus increase in bulk like the drops of rain or hail-stones. Dr. Green says, "that many parts of snow are of a regular figure, for the most part so many little rowels or stars of six points, and are as perfect and transparent ice as any seen on a pond. Upon each of these points are other collateral points set at the same angles as the main points themselves; among these there are divers others, irregular, which are chiefly broken points and fragments of the regular ones. Others also, by various winds, seem to have been thawed and frozen again into irregular clusters; so that it seems as if the whole body of snow was an infinite mass of icicles irregularly figured. That is, a cloud of vapours being gathered into drops, those drops forthwith descend, and in their descent, meeting with a freezing air as they pass through a colder region, each drop is immediately frozen into an icicle, shooting itself forth into several points; but these still continuing their descent, and meeting with some intermitting gales of warmer air, or, in their continual waftage to and fro, touching upon each other are a little thawed, blunted, and frozen into clusters, or entangled so as to fall down in what we call flakes." But we are not, (says the author of the "Contemplative Philosopher,") to consider snow merely as a curious phenomenon. The Great Disposer of universal bounty has so ordered it, that it is eminently subservient, as well as all the works of creation, to his benevolent designs.

"He gives the winter's snow her airy birth,And bids her virgin fleeces clothe the earth."SANDYS.P.T.W.

MONKEYS AT GIBRALTAR

Though Gibraltar abounds with monkeys, there are none to be found in the rest of Spain; this is supposed to be occasioned by the following circumstance;—The waters of the Propontis, which anciently might be nothing but a lake formed by the Granicus and Rhyndacus, finding it more easy to work themselves a canal by the Dardanelles than any other way, spread into the Mediterranean, and forcing a passage into the ocean between Mount Atlas and Calpe, separated the rock from the coast of Africa; and the monkeys being taken by surprise, were compelled to be carried with it over to Europe, "These animals," says a resident at Gibraltar, "are now in high favour here. The lieutenant-governor, General Don, has taken them under his protection, and threatened with fine and imprisonment any one who shall in any way molest them. They have increased rapidly, of course. Many of them are as large as our dogs; and some of the old grandfathers and great-grandfathers are considerably larger. I had the good fortune to fall in with a family of about ten, and had an opportunity of watching for a time their motions. There appeared to be a father and mother, four or five grown-up children, and three that had not reached the years of discretion. One of them was still at the breast; and although he was large enough to be weaned, and indeed made his escape as rapidly as the mother when they took the alarm, it was quite impossible to restrain laughter when one saw the mother, with great gravity, sitting nursing the little elf, with her hand behind it, and the older children skipping up and down the walls, and playing all sorts of antic tricks with one another. They made their escape with the utmost rapidity, leaping over rocks and precipices with great agility, and evidently unconscious of fear."

W.G.C.

The Selector, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE GREAT WORLD OF FASHION

Satire is the pantomime of literature, and harlequin's jacket, his black vizor, and his eel-like lubricity, are so many harmless satires on the weak sides of our nature. The pen of the satirist is as effective as the pencil of the artist; and provided it draw well, cannot fail to prove as attractive. Indeed, the characters of pantomime, harlequin, columbine, clown, and pantaloon, make up the best quarto that has ever appeared on the manners and follies of the times; and they may be turned to as grave an account as any page of Seneca's Morals, or Cicero's Disputations; however various the means, the end, or object, is the same, and all is rounded with a sleep.

"The Great World," in the language of satire, is the "glass of fashion and the mould of form." Its geography and history are as perpetually changing as the modes of St. James's, or the features of one of its toasted beauties; and what is written of it to-day may be dry, and its time be out of joint, before it has escaped the murky precincts of the printing-house. It is subtlety itself, and we know not "whence it cometh, and whither it goeth." Its philosophy is concentric, for this Great World consists of thousands of little worlds, usque ad infinitum, and we do well if we become not giddy with looking on the wheels of its vicissitudes.

We know not whom we have to thank for the pamphlet of sixty pages—entitled "A Geographical and Historical Account of the Great World"—now before us. It bears the imprint of "Ridgway, Piccadilly," so that it is published at the gate of the very region it describes—like the accounts of Pere la Chaise, sold at its concierge. Annexed is a Map of the Great World—but the author has not "attempted to lay down the longitude; the only measurements hitherto made being confined to the west of the meridian of St. James's Strait." Then the author tells us of the atomic hypothesis of the formation of the Great World. "These rules, for the performance of what appears to be an atomic quadrille, are furnished by Sir H. Davy, elected by the Great World, master of the ceremonies for the preservation of order, and prescribing rules for the regulation of the Universe." "The surface of the Great World, or rather its crust, has been ascertained to be exceedingly shallow."

The inhabitants of the Great World, in its diurnal rotation, receive no light from the sun till a few hours before the time of its setting with us, when it also sets with them, so that they are inconvenienced for a short time only, by its light. In its annual orbit, it has but one season, which, though called Spring, is subject to the most sudden alternations of heat and cold. The females have a singular method of protecting themselves from the baneful effects of these violent changes, which is worthy of notice:—they wrap themselves up, during the short time the sun shines, in pelisses, shawls, and cloaks, their heads being protected by hats, whose umbrageous brims so far exceed in dimensions the little umbrellas raised above them, that a stranger is at a loss to conjecture the use of the latter. Shortly after the sun has set, these habiliments are all thrown off, dresses of gossamer are substituted in their place, and the fair wearers rush out into the open air, to enjoy the cool night breezes.

This is but the "Companion to the Map." The Voyage to the several Islands of the Great World, "is in a frame-work of the adventures of Sir Heedless Headlong, who neither reaches the Great World by a balloon, nor Perkins's steam-gun. He cruises about St. James's Straits, makes for Idler's Harbour, in Alba; is repulsed, but with a friend, Jack Rashleigh, journeys to Society Island, lands at Small Talk Bay, and makes for the capital, Flirtington. He first visits a general assembly of the leaders of the isle. At the house of assembly the rush of charioteers was so great, that it is impossible to say what might have been the consequence of the general confusion, or how many lives might have been lost, but for the interference of a little man in a flaxen wig, and broad-brimmed hat, with a cane in his hand, whose authority is said to extend equally over ladies and pickpockets of all degrees."18 Then comes an exquisite bit of badinage on that most stupid of all stupidities, a fashionable rout.

"On entering the walls, my surprise may be partly conceived, at finding those persons, whom I had seen so eagerly striving to gain admittance, crowded together in a capacious vapour bath, heated to so high a temperature, that had I not been aware of the strict prohibition of science, I should have imagined the meeting to have been held for the purpose of ascertaining, by experiment, the greatest degree of heat which the human frame is capable of supporting. That they should choose such a place for their deliberations upon the welfare of the island, appeared to me extraordinary, and only to be accounted for upon the supposition that it was intended to carry off, by evaporation, that internal heat to which the assemblies of legislators of some other countries are known to be subject. Judging from the grave and melancholy countenances of the persons assembled, I councluded the affairs of the island to be in a very disasterous state; and I could discover very little either said or done, at all calculated to advance its interests. Of the capital itself, some members said a few words; but, to use the language of our Globe, in so inaudible a tone of voice, that we could scarcely catch their import. The principal subject of their discussion consisted of complaining of the extreme heat of the bath, and mutual inquiries respecting their intention of immersing themselves in any others that were open the same night."

He next satirizes a fashionable dinner, the parks, the Horticultural Society, some pleasant jokes upon a rosy mother and her parsnip-pale daughters, and an admirable piece of fun upon the female oligarchy of Almacks.

"From hence I made a trip to Crocky's Island, situated on the opposite side of the Strait. On landing at Hellgate, within Fools' Inlet my surprise was much excited by the prodigious flocks of gulls, pigeons, and geese, which were directing their flight towards the Great Fish Lake, whither I, too, was making my way. I concluded their object was to procure food, of which a profusion was here spread before them, consisting of every thing which such birds most delight to peck at; but no sooner had they settled near the bank, than they were seized upon by a Fisherman, (who was lying in wait for them,) and completely plucked of their feathers, an operation to which they very quietly submitted, and were then suffered to depart. Upon inquiring his motive for what appeared to me a wanton act of cruelty, he told me his intention was to stuff his bed with the feathers; 'or,' added he, 'if you vill, to feather my nest.' Being myself an admirer of a soft bed, I saw no reason why I should not employ myself in the same way; but owing, perhaps, to my being a novice in the art, and not knowing how to manage the birds properly, they were but little disposed to submit themselves to my hands; and, in the attempt, I found myself so completely covered with feathers, that which of the three descriptions of birds aforesaid I most resembled, it would have been difficult to determine. The fisherman, seeing my situation, was proceeding to add to the stock of feathers which he had collected in a great bag, by plucking those from my person, when, wishing to save him any further trouble, I hurried back to Hellgate."

We cannot accompany Sir Heedless any further; but must conclude with a few piquancies from the Vocabulary of the Language of the Great World, which is as necessary to the enjoyment of fashionable life, as is a glossary to an elementary scientific treatise:—

At Home.—Making your house as unlike home as possible, by turning every thing topsy-turvy, removing your furniture, and squeezing as many people into your rooms as can be compressed together.

Not at Home.—Sitting in your own room, engaged in reading a new novel, writing notes, or other important business.

Affection.—A painful sensation, such as gout, rheumatism, cramp, head-ache, &c.

Mourning.—An outward covering of black, put on by the relatives of any deceased person of consequence, or by persons succeeding to a large fortune, as an emblem of their grief upon so melancholy an event.

Morning.—The time corresponding to that between our noon and sun-set.

Evening.—The time between our sun-set and sun-rise.

Night.—-The time between our sun-rise and noon.

Domestic.—An epithet applied to cats, dogs, and other tame animals, keeping at home.

Reflection.—The person viewed in a looking-glass.

Tenderness.—A property belonging to meat long kept.

An Undress.—A thick covering of garments.

A Treasure.—A lady's maid, skilful in the mysteries of building up heads, and pulling down characters; ingenious in the construction of caps, capes, and scandal, and judicious in the application of paint and flattery; also, a footman, who knows, at a single glance, what visiters to admit to the presence of his mistress, and whom to refuse.

Immortality.—An imaginary privilege of living for ever, conferred upon heroes, poets, and patriots.

Taste.—The art of discerning the precise shades of difference constituting a bad or well dressed man, woman, or dinner.

Tact.—The art of wheedling a rich old relation, winning an heiress, or dismissing duns with the payment of fair promises.

Album.—A ledger kept by ladies for the entry of compliments, in rhyme, paid on demand to their beautiful hair, complexions fair, the dimpled chin, the smiles that win, the ruby lips, where the bee sips, &c. &c.; the whole amount being transferred to their private account from the public stock.

Resignation.—Giving up a place.

A Heathen.—An infidel to the tenets of ton, a Goth; a monster; a vulgar wretch. One who eats twice of soup, swills beer, takes wine, knows nothing about ennui, dyspepsia, or peristaltic persuaders, and does not play ecarté; a creature—nobody.

Vice.—An instrument made use of by ladies in netting for the purpose of securing their work.

A Martyr.—A gentleman subject to the gout.

Temperate.–Quiet, an epithet applied only to horses.

Bore.—A country acquaintance, or relation, a leg of mutton, a hackney-coach, &c., children, or a family party.

Love.—Admiration of a large fortune.

Courage.—Shooting a fellow creature, perhaps a friend, from the fear of being thought a coward.

Christmas.—That time of year when tradesmen, and boys from school, become troublesome.

OLD POETS

A KISS

Best charge and bravest retreat in Cupid's fight,A double key which opens to the heart,Most rich, when most his riches it impart,Nest of young joys, schoolmaster of delight,Teaching the mean at once to take and give,The friendly stay, where blows both wound and heal,The petty death where each in other live,Poor hope's first wealth, hostage of promise weak,Breakfast of love.SIR P. SYDNEY.SIGHT

—–Nine things to sight required areThe power to see, the light, the visible thing:Being not too small, too thin, too nigh, too far,Clear space, and time the form distinct to bring.J. DAVIES.MERCY AND JUSTICE

Oh who shall show the countenance and gesturesOf Mercy and Justice; which fair sacred sisters,With equal poise doth ever balance even,The unchanging projects of the King of heaven.The one stern of look, the other mild aspecting,The one pleas'd with tears, the other blood affecting;The one bears the sword of vengeance unrelentingThe other brings pardon for the true repenting.J. SYLVESTERI know that countenance cannot lieWhose thoughts are legible in the eye.M. ROYDON.INGRATITUDE

Unthankfulness is that great sin,Which made the devil and his angels fall:Lost him and them the joys that they were in,And now in hell detains them bound in thrall.SIR J. HARRINGTON.Thou hateful monster base ingratitude,Soul's mortal poison, deadly killing-wound,Deceitful serpent seeking to delude,Black loathsome ditch, where all desert is drown'd;Vile pestilence, which all things dost confound.At first created to no other end,But to grieve those, whom nothing could offend.M. DRAYTON.HEAVEN

From hence with grace and goodness compass'd round,God ruleth, blesseth, keepeth all he wrought,Above the air, the fire, the sea and groundOur sense, our wit, our reason and our thought;Where persons three, with power and glory crown'd,Are all one God, who made all things of naught.Under whose feet, subjected to his graceSit nature, fortune, motion, time and place.This is the place from whence like smoke and dustOf this frail world, the wealth, the pomp, the power,He tosseth, humbleth, turneth as he lust,And guides our life, our end, our death and hour,No eye (however virtuous, pure and just)Can view the brightness of that glorious bower,On every side the blessed spirits beEqual in joys though differing in degree.E. FAIRFAX.MARRIAGE

In choice of wife prefer the modest chaste,Lilies are fair in show, but foul in smell,The sweetest looks by age are soon defaced,Then choose thy wife by wit and loving well.Who brings thee wealth, and many faults withal,Presents thee honey mix'd with bitter gall.D. LODGE.PRIDE

Pride is the root of ill in every state,The source of sin, the very fiend's fee:The bead of hell, the bough, the branch, the tree;From which do spring and sprout such fleshly seeds,As nothing else but moans and mischief breeds.G. GASCOIGNE.SPIRIT OF THE Public Journals

NOTES FROM THE LONDON REVIEW, NO. 1. ANCIENT AND MODERN LUXURIES

As a learned doctor, a passionate admirer of the Nicotian plant, was not long since regaling himself with a pinch of snuff, in the study of an old college friend, his classical recollections suddenly mixed with his present sensation, and suggested the following question:—"If a Greek or a Roman were to rise from the grave, how would you explain to him the three successive enjoyments which we have had to-day after dinner,—tea, coffee, and snuff? By what perception or sensation familiar to them, would you account for the modern use of the three vulgar elements, which we see notified on every huckster's stall?—or paint the more refined beatitude of a young barrister comfortably niched in one of our London divans, concentrating his ruminations over a new Quarterly, by the aid of a highly-flavoured Havannah?" The doctor's friend, whose ingenuity is not easily taken at fault, answered, "By friction, which was performed so consummately in their baths. It is no new propensity of animal nature, to find pleasure from the combination of a stimulant, and a sedative. The ancients chafed their skins, and we chafe our stomachs, exactly for that same double purpose of excitement and repose (let physiologists explain their union) which these vegetable substances procure now so extensively to mankind. In a word, I would tell the ancient Greeks or Romans, that the dealer in tea, coffee, tobacco, and snuff, is to us what the experienced practioner of the strigil was to them; with this difference, however, that while we spare our skins, our stomachs are in danger of being tanned into leather."

THE STAGE

We may compare tragedy to a martyrdom by one of the old masters; which, whatever be its merit, represents persons, emotions, and events so remote from the experience of the spectator, that he feels the grounds of his approbation and blame to be in a great measure conjectural. The romance, such as we generally have seen it, resembles a Gothic window-piece, where monarchs and bishops exhibit the symbols of their dignity, and saints hold out their palm branches, and grotesque monsters in blue and gold pursue one another through the intricacies of a never-ending scroll, splendid in colouring, but childish in composition, and imitating nothing in nature but a mass of drapery and jewels thrown over the commonest outlines of the human figure. The works of the comedian, in their least interesting forms, are Dutch paintings and caricatures: in their best, they are like Wilkie's earlier pictures, accurate imitations of pleasing, but familiar objects—admirable as works of art, but addressed rather to the judgment than to the imagination.

ENGLISH WOMEN

Nothing could be more easy than to prove, in the reflected light of our literature, that from the period of our Revolution to the present time, the education of women has improved among us, as much, at least, as that of men. Unquestionably that advancement has been greater within the last fifty years, than during any previous period of equal length; and it may even be doubted whether the modern rage of our fair countrywomen for universal acquirement has not already been carried to a height injurious to the attainment of excellence in the more important branches of literary information.

But in every age since that of Charles II, Englishwomen have been better educated than their mothers. For much of this progress we are indebted to Addison. Since the Spectator set the example, a great part of our lighter literature, unlike that of the preceding age, has been addressed to the sexes in common: whatever language could shock the ear of woman, whatever sentiment could sully her purity of thought, has been gradually expunged from the far greater and better portion of our works of imagination and taste; and it is this growing refinement and delicacy of expression, throughout the last century, which prove, as much as any thing, the increasing number of female readers, and the increasing homage which has been paid to the better feelings of their sex.

Mr. Lee, the high-constable of Westminster, in the Police Report, says, "I have known the time when I have seen the regular thieves watching Drummonds' house, looking out for persons coming out: and the widening of the pavement of the streets has, I think, done a great deal of good. With respect to pick-pocketing, there is not a chance of their doing now as they used to do. If a man attempts to pick a pocket, it is ten to one if he is not seen, which was not the case formerly."

CRIME IN PARIS

Vidocq, in his Memoires, relates, that in 1817, with twelve agents or subordinate officers, he effected in Paris the number of arrests which he thus enumerates:—