полная версия

полная версияThe Quest of the Simple Life

Earth-hunger is without doubt the most wholesome passion men can entertain, and if Governments were wise they would do all they could to fortify and gratify it. On the contrary, the settled policy of English Government is entirely hostile to it. There is no country where it is so difficult to acquire freehold land in small quantities—a subject on which I shall have more to say presently. Bad land-laws lie at the back of what we call the urban tendencies of modern life. If fifty years ago the Irish peasantry had had the same facilities for acquiring land that they have to-day, it is safe to say that there would have been little or no emigration, for never was there race that left the land of its fathers with such bitter and entire reluctance as the Irish. The English peasant shares the same reluctance, though his slower nature is incapable of expressing it with the same volubility of anguish. Give him enough land to live upon; make him a proprietor instead of a serf; let him have fair railway rates, so that his produce can fetch its proper price in the markets, and there were no man so proud and so content as he. But this is just what the feudal laws of England will not do for him; and so millions of acres fall out of cultivation and farms go a-begging because the men who could have kept them prosperous have been forced to sell their thews and muscles to be prostituted in the dismal drudgeries of cities.

There is an even worse result. Earth-hunger has been displaced by Money-hunger. Simple ideas of life must needs perish where the nature of a nation's life makes them difficult or impossible of attainment. A country-born youth might keep to the soil, if he saw the slightest hope that the soil would keep him; when he sees that this is impossible he files to cities, because he believes that there is more gold to be picked up in the city mire in a month than can be won from the ploughed fallow in a year. It is not until the altars of Pan are overthrown that the worship of Mammon is triumphant, and the mischief is that when the great god Pan is driven away he returns no more. When once Money-hunger seizes on a nation, that primitive and wholesome Earth-hunger—old as the primal Eden, where man's life began—is stifled at the birth; the spade and harrow rust, and instead of swords being beaten to ploughshares, ploughshares are beaten into swords for the use of soldiers who are the gladiators of commercial avarice; the wealth of the country runs into the swamp of speculation; the scripture of Nature is cast aside for the blotted pages of the betting-book; sport becomes not a means of recreation but of gambling; and instead of sturdy races bred upon the soil, and drawing from the soil solid qualities of mind and body, you have blighted and anaemic races, bred amid the populous disease of cities, and incapable of any task that shall demand steady energy, continuous thought, or sober powers of reflection or of will.

CHAPTER V

HEALTH AND ECONOMICS

Enough has been said to show that I never heartily settled to a town life, and that the obstacle to content was my own character. Mere discontent with one's environment, however useful it may be as an irritant to prevent stagnation and brutish acquiescence, obviously does not carry one very far. Men may chafe for years at the conditions of their lot without in any way attempting to amend them. I soon came to see that I was in danger of falling into this condition of futility. I was, therefore, forced to face the question whether my continual inward protest against the kind of life which I led was founded on anything more stable than an opinion or a sentiment? No man ever yet took a positively heroic or original course for the sake of an opinion. Opinion must become conviction before it has any potency to change the ordering of life. I saw plainly that I must either bring my thoughts to the point of conviction or discard them altogether.

There is a good phrase which is sometimes used about men who are members of a party, without in any way entering into its propagandist aims—we say that they 'do not play the game.' They may have excellent philosophic reasons for their aloofness, or even admirable scruples; but parties do not ask for either. Parties ask for party loyalty, and to give this loyalty personal scruples must be set aside. I could not but apply this doctrine to my own state of mind. London asked me to play the game, and I was not playing it. It was impossible to put heart into a kind of life which I inwardly detested. I did my day's work with a mind divided; and, although no one could accuse me of wilful negligence, yet a child could see that my work missed that quality of entire efficiency which makes for success. I might count myself much superior to men like Arrowsmith by the possession of superior sentiments, yet, in the long run, my sentiment debilitated me, and his destitution of sentiment was a source of power to him in the kind of work we both had to do. To the man who detests the nature of his employment as I detested mine, I would say at once, either conquer your detestation or change your work. Work that is not genuinely loved cannot possibly be done well. It is no use chafing and fretting and wishing that you lived in the country, if you know perfectly well that you have not the least intention of living anywhere but in the town. If it is town life you are really bent upon, the sooner rustic instincts are uprooted the better for you. London can prove herself a complaisant mistress to those who desire no other, but she will give nothing to those who flout her in their hearts. In plain words there is no middle course between accepting the yoke or finally rejecting it; either course may be justified, but it is the silliest folly to accept with complacency a yoke which you mean to shake off the moment you have courage or opportunity to revolt. London marks such dissemblers with an angry eye, as captains mark reluctant soldiers; and if time holds no disgrace for them it will certainly bring them no advancement.

Were my fine theories composed of mere fluid sentiment, or had they some more consistent element in them which was capable of hardening into invincible conviction? That was my problem. It was debated in season and out of season. Gradually the two dominant factors in the problem became evident; they were health and economics.

There could be no question about health. It was true that I had suffered from no serious illness in my life, but London kept me in a normal state of low vitality. I had constant headaches, fits of depression, and minor physical derangements. I rarely knew what it was to wake in the morning with that clear joyousness of spirit which marks vigorous vitality. A London winter I dreaded, and I had good reason for my dread. When the fog lay on the town an unbearable oppression lay also on my spirits. Imagination had little to do with this oppression; it was the physical result of lack of oxygen. It was the same with my children; they grew pinched and bleached in face, and went about their little tasks with the slowness of old men. It is stated, I believe, that London is the healthiest city in the world; no doubt it is true as regards the actual percentage of disease to the immense population, but statistics take no account of lowered vitality. Without being actually ill, vitality may be reduced to a point at which existence becomes a kind of misery. Alcohol dissolves for a time the cloud on the mind, the incubus upon the energies; and the relief is so great that men do not think of the price they pay for it. No wonder public-houses are the landmarks of London locomotion; they are the Temples of Oblivion, where the devitalised multitudes seek to forget themselves, that they may regain the courage to live at all.

For myself, I had sense to know that stimulants of this kind were a remedy much worse than the disease. The only stimulant, at once safe and effectual, which I needed was fresh air. The moment I found myself among the hills a miraculous change was wrought in me. I had not breathed that quick and vital air for an hour before a glow ran through my veins more delightful, and much more enduring, than the glow of wine. A single night in some small cottage chamber—where the very bed had a cool scent of flowers and lawns, where the open window admitted air fresh from pine forest and mountain streams, where the silence was so deep that one's pulse seemed to tick aloud like a watch—and I awoke a man renewed. Six o'clock, or even five, was not too soon for all my little household to be astir. We were all alike eager for the open air; for the walk, bare-footed, through the dewy grass to the mountain pool; for the shock and thrill of that green water into which we plunged delighted; and in those prolonged and pure ablations I think our spirits shared. The bells of laughter rang the livelong day. The cramped mind began to move again, and long abdicated powers of fancy and of humour were restored. Equanimity of body brought evenness of temper; it was incredible to recollect how irritable we had been with one another in those ghastly days of London fog, when the very grating of a chair along the floor made the nerves jump. Even the mind took new edge, for though I did not read much upon a holiday, yet I found that what I did read left a clearness of impression to which I had long been unaccustomed. And what was the root and cause of all this miracle? Fresh air, wholesome food, rude health—nothing more! To feel that it is bliss to be alive, health alone is needed. And by health I mean not the absence of physical ailment or disease, but a high condition of vitality. This the country gave me; this the town denied me. The only question was then, at what rate did I value the boon?

This brought me immediately to the much more complex problem of economics. I knew that men could live in the country on small means, for men did so; but I perceived that the art of living in the country did not come by nature. Every one supposes that he can drive a horse or grow potatoes; and, when we recollect how many thousands of men go to Canada to take up agricultural pursuits without the least knowledge of the business, it is clear that the belief is general that any man can farm. I may claim the merit of freedom from this popular delusion. I not only knew that I could not farm, but I did not wish to be a farmer. What I wished was to live in the country in some modest way that answered to my needs; to earn by some form of exertion a small income; and at the most, to grow my own vegetables, catch my own fish, and snare my own rabbits.

A legacy of two hundred a year would have served my purpose admirably, but modesty forbade me laying my case before benevolent millionaires, and a destitution of maiden aunts put an end to any hopes of a bequest by natural causes.

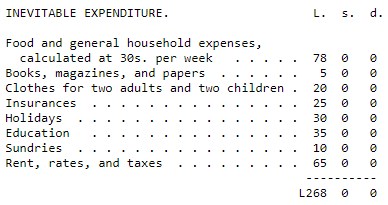

What was my precise position then? I had a salary of two hundred and fifty pounds a year. An investment that had turned out fortunately gave me about forty pounds a year. I had done from time to time a little work for the press, which had been worth to me about thirty pounds a year more. My total budget showed, then, an annual income of three hundred and twenty pounds, which I found barely sufficient for my needs as a dweller in towns. If I migrated to a cottage, how would matters stand with me? I should lose my two hundred and fifty pounds per annum of course, and this was an alarming prospect. But, on the other hand, I reminded myself that I had never really possessed it. I prepared various tables in which I arranged the items of my expenditure under two heads, viz. the expenditure that was inevitable, and the expenditure that was evitable, because it was the result of town life. I shall best explain by giving a sample of these tables:—

TABLE I.

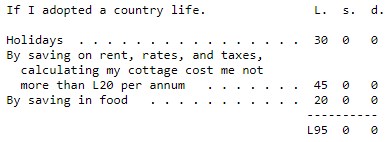

TABLE II.

EVITABLE EXPENDITURE.

It will be seen that I allowed no reduction in clothes and books, for I did not wish my children to be dressed as beggars, or to be ignorant of current literature.

It does not need the eye of a chartered accountant to perceive that whatever may be said for Table II., Table I. is not satisfactory. In it I accounted for only 268 pounds, whereas I have already stated my total income was 320 pounds. What became of the 52 pounds which found no record in my ingenuous schedule? I could not tell, but I was pretty sure that it was absorbed in the petty wastefulness of town life. Londoners are so accustomed to constant daily expenditure in small ways, that it occurs to no one to ascertain how considerable an encroachment this aggregate expenditure is upon the total yearly income. In all but very fine weather I must needs use some means of public conveyance every day; there was a daily lunch to be provided; and when work kept me late at the office there was tea as well. One can lunch comfortably on a shilling or eighteenpence a day; and I knew places where I could have lunched for much less, but they were in parts of the town which I could not reach in the brief time at my disposal. Moreover, one must needs be the slave of etiquette even though he be a clerk, and if all the staff of an office frequent a certain restaurant, one must perforce fall into line with them under penalty of social ostracism. Thus, whether I liked it or not, for five days in the week I had to spend eighteenpence a day for lunch, and fourpence for teas; and if we add those small gratuities which the poorest men take it as a point of honour to observe, here was an annual expenditure of 25 pounds. Taking one thing with another 5 pounds might be added for 'bus and railway fares; so that only 22 pounds is left to be accounted for. And now, if we return to Table II., it is obvious that my income of 320 pounds per annum was only nominal, because a very great part of it was really spent in keeping up a position which a town life imposed upon me. Before I touched a single penny of my nominal income of 250 pounds per annum, I had paid 30 pounds per year in the daily expenses inevitable to my position, and 65 pounds for rent and taxes, which was quite 45 pounds more than I ought to pay. Education comes also to be considered at this point. My two children went to a very respectable school at the cost of a little more than 15 pounds per annum each. No doubt I might have sent them to a Board school, where they would have received a better education; but in the part of London where I lived there was no Board school within easy reach, and besides this, though I hate the pretension of gentility, manners and companionship have to be considered as well as education in the choice of a school. A child may take no harm by sitting on the same bench with village children, but the London gamin is not a desirable acquaintance. In this, as in other matters, I paid through the nose for my position; and the convention cost me a clear 35 pounds per annum. Thus I calculated that out of a nominal income of 250 pounds per annum 100 pounds was paid as a tax to convention and respectability.

I have no doubt that a good many flaws may be found in these calculations; but one point is beyond dispute, viz., that a town income is always more apparent than real. Money is worth no more than its purchasing power. The business man who is offered 1000 pounds per annum in New York against 700 pounds per annum in London, refuses the offer unless it carries with it great contingent advantages, because he knows perfectly well that 700 pounds a year in London is worth a good deal more than 1000 pounds a year in New York. But the same kind of prudent calculation is seldom applied to the case of town versus country living at home. It is impossible to persuade the labourer that a pound a week in London is really less than fifteen shillings a week in the country. Men are dazzled by mere figures, and there is no country clerk who would not jump at the idea of a fifty pounds a year rise in London, though ten minutes spent over a sum in addition and subtraction would be sufficient to assure him that he would not be enlarging his income but diminishing it. A man has to live upon a certain scale suited to his needs and tastes, but the income which makes this kind of life possible is a variable quantity. It is not by what men earn in the aggregate that their incomes should be measured, but by what they have left when the necessary cost of living is defrayed. If it costs a man fifty pounds a year more to live in London than in the country, he is obviously no better off by the extra fifty pounds he earns in London. He is not earning fifty pounds for himself but fifty pounds for the landlord, the rate-collector, the gas-man, the restaurant proprietor, the omnibus and railway companies. His gold never reaches his own pocket; it is filched from him by dexterous thieves; it gleams before him for an instant like the coin spun in the air by the conjurer or thimble-rigger, and then vanishes for ever. Yet I have found few men keen enough to penetrate the delusion; it would seem they love to be deluded, and by their conduct justify the satiric lines of Hudibras—

Doubtless the pleasure is as greatTo cheated be as 'tis to cheat.In most things I claim to be no wiser than my fellow-men, but in this I knew myself wiser; I knew where I was cheated. I knew that the schoolmaster who cost me thirty pounds a year was a licensed footpad; half the money spent in restaurants and tea-shops was blackmail paid to respectability; the landlord who took his forty-five pounds a year from my pocket was a mere robber, who took advantage of the need I had to live in a certain locality that I might attend to my vocation. Not only were my brains exploited that my employer might maintain a sumptuous house at Kensington, but the wage he paid me was exploited by a host of other people, who had houses of their own to maintain. Before I could feed my children I must help to pay for and cook the dinner of the folk who lived on the dividends of railways and omnibus companies. On the way to my office the tailor took toll of me by forcing me to wear a garb which I detested, simply because I dared wear no other garb. I could not even drink plain water but that some one was the richer. I was the common gull of the thing called convention. I was plucked to the skin, and if my skin had been worth turning into leather, some one would have put in a claim to that. Even for my skin, poor asset as it was, some one did wait, when it had ceased to be of use to me, for London cemeteries declare dividends upon the dead. My case reminded me of an old gentleman I once knew, who wore so many coats, waistcoats, and shirts to keep warmth in a body of singular attenuation, that it was commonly said that by the time James Smith undressed at night there was very little James Smith that was discoverable. Certainly by the time London had done wringing gold out of me there was very little gold left that was my own.

There was, however, one kind of comfort to be deduced from these reflections; if I was not nearly so well off as I appeared to be, I had all the less to lose. Rightly considered it would not be 250 pounds per annum that I should lose by leaving London, for I had never possessed that sum, I calculated my real loss at something nearer 150 pounds, and this seemed not so terrible a thing. I had my forty pounds a year for certain. I had the small earnings of my pen, and with abundant time upon my hands I saw every reason why these should be increased. Could I face a new kind of life upon an income of seventy pounds per annum? Ah, how anxiously that problem was debated with my wife, many a night when the children were abed! The natural conservatism of woman had a great deal to say in these debates. 'It was all very well,' said my wife, 'to do these little sums on paper, but suppose the facts did not correspond? Suppose I found no cottage at twenty pounds a year, and no decent school at sixpence a week? Then the world was full of writers for the press.' (I frowned.) 'Not of course like you, not half so good,' she added with a smile, 'but how do you know that you will succeed? Show me a fixed income of 100 pounds a year, and I would chance it, for I can live simply enough,' she would say, 'and am as fond of liberty as you.'

She might have added what I knew to be true, that the penalties of London life fell heavier upon her than me. I was not insensible to the instantaneous lightening of spirits that happened with her when she was able to forsake the abominable purlieus of the cellar-kitchen where her life was spent; and although I knew not half her toils, nor half her dejections and anxieties, which were sedulously kept from me, yet I was not wholly blind. I had seen her too amid the roses of a cottage garden flying the colour of long-forgotten roses in her cheeks; in the hay-field shaking off a dozen years in as many hours; and although she was always young to me, she never seemed so young and sweet as when we walked a honeysuckled lane together. Her desire was with me I knew well; she had no fear of poverty, and would have been content with plainer fare than I; but her children made her prudent.

At last the one thing happened which made her prudence coincide with her desires; one of the children sickened with a languor that was the precursor of disease, and the doctors said that only country air could bring back strength. And then fate itself took the whole matter out of my control. Something happened in the city—I know not what—and the firm I served came near to shipwreck. Business shrank to a diminished channel, and the staff of clerks must needs be reduced. I have said some hard words of my employer as the exploiter of my labour; he will appear no more in this history, and my last word about him shall be justly kind. He broke the news of his misfortune to me with a delicacy that made me respect him, and with a hesitating painful shame that made me pity him. He praised me beyond my merit for my twenty years of service; he had hoped to keep me with him for another twenty years, and I believe he spoke the truth when he said it pained him to think that his misfortunes should be mine. He handed me in silence a cheque for fifty pounds. He then shook my hand heartily, murmured some vague words about hoping to reinstate me if things should mend, and hurried from me; and in his broken look and bowed shoulders I read the prophecy that his days of fortune and success were gone for ever. The little tragedy was played out in less than ten minutes. I locked my desk, put on my hat and coat, and went out into the street; and my heart felt a pang at leaving the place which I should never have imagined possible. I had walked fully half a mile before another thought occurred to me. My blood suddenly sang in my veins, and I remembered that I was an emancipated slave; at last I was Free!

CHAPTER VI

IN SEARCH OF THE PICTURESQUE

I was free, but what was I to do with my freedom? Ingenious apologists for slavery used to argue that the slave was much happier as a bondman than a freeman, as long as the conditions of his bondage were not unendurably harsh: but no one ever knew a slave who held this creed. There never was a slave who did not prefer his dinner of herbs, earned by his own labour, to the stalled ox of luxurious captivity. For my part, I thought the air never tasted so sweet as on that morning of my liberation. I walked slowly, drawing long breaths, that I might taste its full relish, as a connoisseur passes an exquisite and rare wine over his palate, that he may discriminate its subtleties. I became a lounger, and took the pavement with the air of a gentleman at ease. I wandered into Hyde Park, paid my penny for a seat, and sat down almost dizzy with the unaccustomed thought that there was not a human being in the universe who, at that moment, had the smallest claim to make upon my time or energy. An hour passed in a kind of ecstatic dream. It chanced to be a morning when Queen Victoria was driving from Paddington to Buckingham Palace, and every instant the throng of carriages increased. Standing on my seat, I saw an immense lane of people, silent as a wood; a contagious shiver stirred them, like a gust of wind amongst the leaves; I saw the distant glitter of helmets and cuirasses, and the pageant swept along with that one tired, kindly, homely face for its centre of attraction, luring loyalty even from a heart so republican as mine by its air of patient weariness. I thought, and I believed the thought sincere, that I would not have exchanged places with her who was the mistress of so many peoples, the Empress of such indeterminable Empire. My new-born loyalty was three-parts pity. Had she, who sat there in such 'lonely splendour,' ever known the day, since as a young girl the heavy rod of empire was intrusted to her frail and unaccustomed hands, when she woke to say, 'This day I am free, I will go where I will, do as I please, and none shall stay me?' Yet I, a manumitted clerk, had come upon this singular and glad day; and I had it in my heart to say with Emerson, 'Give me health and a day, and I will make the pomp of empire ridiculous.'