полная версия

полная версияChambers's Edinburgh Journal, No. 428

Nothing was done, however, in following up these recommendations, till the subject was brought before the House of Commons by Dr John Bowring, in 1847. The consequence of his appeal was, that a coin denominated a florin, and representing the tenth of a pound, was struck, and put in circulation. It was, however, considered 'an unfortunate specimen of Royal Mint art,' and the issue was discontinued, though a few specimens still linger unforbidden among us. The matter is thus at a stand-still, and may probably not be agitated again till the people generally are more impressed with its importance, and disposed to urge it on the legislature.

The first thing wanted is obviously an abundant issue of acceptable florins. No matter though the coin be recognised by the ignorant as a two-shilling piece, rather than as the tenth of a pound; it is a decimal coin with which they may become familiar without disturbing their old ideas and modes of reckoning. The single step that would then remain to be taken is the decisive one—the introduction of the coin equivalent to one-tenth of a florin, accompanied by the withdrawal of the representatives of duodecimal division, and a legislative enactment that all accounts kept in public offices, or rendered in private transactions, should be in the decimal denominations.

The only difficulty which has appalled the advocates of the decimal system, is with respect to the cent-piece. It is said to be too small for a silver coin, too large for a copper, and mixed metals find no favour at the Mint. But if it is to be a denomination in accounts, it must have a representative coin, and a silver cent could be very little smaller than our present 3d.-piece. 'The great mass of the people,' says Mr Norton (a correspondent of the Athenæum on this subject), 'will not adopt an abstraction; you must give them something which they can see, handle, and call by name, if you wish them to take notice of it in their reckonings.' Mr Taylor, and some other writers, have proposed to evade this difficulty by passing over the cents altogether, and counting only by pounds, florins, and millets. The French, say they, have in theory a decimally graduated scale, yet they always reckon by francs, and cents, which are 100ths of francs; the intervening decime being ignored in practice. So, likewise, the Americans have the dollar, the dime (its tenth part), the cent (its hundredth), and the mill (its thousandth). 'It is now nearly thirty years,' says Mr John Quincy Adams, in his report to Congress in 1821, 'since our new moneys of account have been established. The dollar and the cent have become familiarised to the tongue, but the dime and the mill are so utterly unknown, that now, when the recent coinage of dimes is alluded to, it is always necessary to inform the reader that they are ten-cent pieces. Ask a tradesman in any of our cities what is a dime or a mill, and the chances are four in five that he will not understand your question.' This, however, we cannot help considering one of the greatest inconveniences of transatlantic and continental reckonings. We are accustomed to talk of amounts in as small numbers as possible; and one of the great advantages we see in decimal gradations is, that we should never have a number above 9, except in pounds. There is something not only troublesome but indefinite, in the idea of ten and twenty in comparison with one and two; and a French account in francs bewilders us when it amounts to thousands and millions. Probably the half and quarter francs of France, and the half and quarter dollars of America, have been the means of exploding the decimals next below them; and on this ground we differ from those who plead for the continuance of our present shillings and sixpences, as half and quarter florins. The shilling is a coin so inseparably connected with 12 and 20, that no decimal system will obtain while it exists. It is useless to say, that it would be retained only as a circulation coin, and not as a denomination in accounts; for so long as we have it at all, we will certainly reckon from it and by it. For purposes of common barter, there ought to be a two-cent piece, a four-cent, and perhaps a seven-cent; and thus we shall be compelled to think decimally. 'If it is worth while to alter at all,' says Mr Taylor, 'ought we not to go the whole required length, and aim without timidity at the possession of a scale complete at once within itself, and so escape an indefinite prolongation of the purgatory of transition? In a change like the one under consideration, the work of pulling down an old system is far more difficult than that of building up another, and every prop must be removed before it will fall.'

With respect to the copper coins, there seems to be no hurry about disturbing them. It appears that the Dutch stiver and the French sou have maintained their place in spite of legislation. So, probably, would the English penny, and properly enough as a 4-millet piece. We fear our poor people would feel it to be an attempt to mystify them, were the government to withdraw this familiar coin and substitute a 5-millet piece, as some have recommended, for the sake of establishing a binary division of the cent. It would, doubtless, be considered desirable, as an ulterior measure, to have a more exact copper coinage, marked as one millet, two millets, and four millets; but when we have, without scruple, passed as the twelfth part of a shilling the Irish penny, which is really only the thirteenth part, we may, in the meantime, use our present copper money, which will differ only a twenty-fifth from the new value attached to it—a discrepancy of no consequence, except to the holders of large quantities, from whom the Mint would be bound to receive it back at the value it bore when issued. These coppers, however, ought not to be used beyond the value of the cent, for then would arise the confusion of dealing with the 100 millets in the florin, or what would popularly be termed an odd half-penny in every shilling. For the same reason, the adjustment of prices, in order to be equitable, should be calculated downwards from the pound and florin, not upwards from the penny. Thus, if a labourer's wages have been 1s. 3d. a day, his employer must not say that 15 pence are 60 farthings—that is, 6 cents; but 1s. 3d. is five-eighths of a florin, which amount to about 6 cents 2 millets.

Such is the plan which has been officially laid down for a decimal coinage, and such the steps needful to carry it out. The only scheme we have seen which materially differs from it is that of Mr H. Norton. He selects for the highest denomination the half-sovereign, and proposes to call it a ducat. The shilling, as now in use, would then be the second denomination; the third, he proposes, should be a cent, equal to about 1-1/5th of a penny, and which, he says, would be fairly represented by our large unmilled pennies, if newly christened; the fourth denomination to be a 'rap,' the tenth of the cent, and somewhat less than half a farthing. The great advantage adduced in favour of this scale is, that it would be much more likely than the other to secure general adoption. The removal of the pound, he says, affects chiefly the higher and educated classes; it leaves the shilling, which is the staple and standard for the masses, and also the penny, with slight alteration, accompanied by the utter removal of the old one. It is also said, that a half-farthing piece would be a great boon to the poor, especially in Ireland. The circumstances alleged in recommendation of this scale, are just what appear to us to be its defects. The continuance of the poor man's penny would not appear a boon if he found there were to be only ten of them for a shilling; especially as many small articles, which were a penny before, would probably be a penny still, the dealers not finding it convenient to adjust the fraction. We well remember the dissatisfaction of the poorer classes in Ireland at the equalisation of the currency in 1825. Hitherto, the native silver coins had been 5d. and 10d. pieces, a British shilling had been a thirteen-penny, and a half-crown, 2s. 8-1/2d. This half-crown was the usual breakfast-money of gentlemen's servants—that is, their weekly allowance for purchasing everything except dinner. When the servant now went to the huckster's, and got, as heretofore, 6d. worth of bread, 9d. worth of tea, 4d. worth of sugar, and 5d. worth of butter, there was only 6d. of change to buy another loaf in the middle of the week, instead of 8-1/2d., which was wont to afford, we will not say what, over and above. It is for a similar reason that we say, if there remain anything which can be either identified or confounded with a penny, it should be lowered rather than raised in value. Small prices are not easily adjusted, and the temptation in the other case lies on the side of the dealer not to alter them. It is more certain, for instance, that a baker will take care to divide 2s. worth of bread into twenty-five penny-loaves, when a penny comes to be the twenty-fifth of a florin, than that he will divide 1s. worth into ten only, if a penny become the tenth of a shilling. And it would be less hardship for the poor housekeeper to find her penny-loaf 1-25th smaller, if she could discern the reduction, than to get only ten for her shilling, even if they were a fifth larger. Besides, we should feel it to be a poverty-stricken thought, that our internal commerce should be reduced to barter in half-farthings' worths, and that our merchants and bankers should have no denomination above the value of 10s. for the enormous sums which figure in their books.

The subject of names is worth a remark or two. The commissioners recommended 'florins,' as affording facilities to foreigners for understanding our monetary system; and in this respect it has advantages. 'Cent' and 'millet' are easily enunciated, and they convey to the educated classes, whether at home or abroad, the relative value of the coins. We cannot say, however, but we would prefer a more familiar nomenclature than florins, cents, and millets. Mr Norton's suggestion, that the names should not only be capable of easy and rapid utterance, but that they should be of the same Teutonic origin as our shilling and penny, is worthy of serious consideration. Dr Bowring, who advocated a strictly decimal scale, suggested the names, 'queens' and 'victorias' for the two middle denominations, leaving pounds and farthings as they were. Now, if it be deemed proper to change the name of the unfortunate florin when it makes its reappearance, 'queen' would be a very pretty substitute; but 'victoria' would soon be mangled down to its first syllable. If this style of nomenclature be preferred, 'prince' would be a more suitable name for the little cent-piece. Mr De Morgan is for 'pounds, royals, groats, and farthings.'

But 'royal' is not capable of rapid enunciation, and 'groat' is decidedly objectionable for designating ten farthings, as it is still sacred to fourpence in the English mind. Whatever the names, the full enunciation of them at first would appear stiff and solemn; but abbreviated modes of expression would soon be established. 'Four-two' would be understood as L.4, 2 (florins), while 'four and two' would convey four florins, two cents. When three denominations were used, it would be 'four-three-two,' there being little danger of a misunderstanding as to whether the 'four' were pounds or florins. So, in writing, it would only be necessary to write after any sum the name of the lowest denomination, as 48, 3, 7c., which would be known as L.48, 3 florins, 7 cents; or, to add ciphers for all lower denominations, as 48300, which, whether pointed or not, would convey L.48, 3, 0, 0.

In a future paper, we will resume the subject of decimals, viewing it with reference to weights and measures; when its advantages will more fully appear, by the facility it affords for the calculation of prices.

WHY THE SCOTCH DO NOT SHUT THE DOOR

Nations have curious and almost unaccountable peculiarities. One interlards conversation with shrugs, and another with expectoration; and a third, by way of indicating satisfaction, rubs its hands. The Scotch have a peculiarity of their own. When they quit a room, they do not shut the door, but merely draw it gently after them, so as to leave it unlatched. Some individuals may not be strictly attached to this practice; but on the whole the Scotch may, for the sake of distinction, be said to be an anti-door-shutting nation. Now, why such should be the case, becomes an interesting philosophical problem.

Much consideration have we spent in pondering on this national oddity, and are free to admit that the conclusions arrived at are not so satisfactory as could be wished. Nevertheless, in default of any better explanation of the phenomenon, what we have to say may possibly carry a degree of weight.

The reason why the Scotch do not shut the door is, as we imagine, highly characteristic. It is not that they are ignorant of the important fact, that doors are made for shutting. They are fully aware that latches are not mere ornamental attributes of doors—things stuck on not to be used. And it cannot be imputed to them, that they leave doors open for the sake of ventilation. In short, if strangers were to guess for a hundred years, they would fail to hit upon the real, true, and particular reason why the Scotch do not shut the door. One would naturally think, that as the act of shutting the door is the prerogative of the person who quits an apartment, it would not by so mindful a people be neglected. And neither it is. There is no neglect in the matter. The Scotch take a profound view of the subject. They institute a rigorous comparison between shutting and not shutting. True, they are not taught to do so, any more than Frenchmen are taught to make gestures. It is in them. They are born with a natural proneness to consider, as if it were a question of algebraic quantities, whether the satisfaction they might impart by shutting the door would not be more than counterbalanced by the dissatisfaction that might accrue from distinctly and unmistakably shutting it. Still, it seems strange how any displeasure could be incurred by the performance of what all the rest of mankind believe to be a mark of good-breeding. Strange, indeed! But it surely will be observed, that much depends on making a principle of a thing. And with respect to good-breeding, what if it can be placed in a double point of sight? It may be the etiquette in some countries to shut the door; but that proves nothing. In Europe, men uncover their heads on entering the presence of the great; in the East, they uncover the feet. Fashions are local. When the Scotch do not shut the door, they act conscientiously, according to ancient national usage. We may be certain that they have deliberately, arithmetically, and cautiously, weighed the question of shutting in its various and delicate bearings; and arrived at the clear conviction that, all things considered, it would be better not to shut!

Of course, the Scotch having, by innate logic, attained to a principle, they adhere to it as a thing which neither argument nor raillery can upset. They have very properly resolved not to be reasoned, nor laughed, nor cudgelled out of their opinion. The door ought not to be shut! That is a truth as effectually demonstrated as any truth in mathematics; and such being the case, they will die rather than yield the point. Let it be understood, therefore, that in these observations we aim not in the slightest degree at proselytising our northern friends. They are a nation of anti-door-shutters, and that, on principle, they will remain to the end of the chapter.

It may, at the same time, be mentioned, that this acute people have no special objection to seeing a door shut, provided anybody else does it. Their principles apply only to shutting by their own hand. What might be very wrong in them, while quitting an apartment, would be proper enough for him who remains. He may rise and shut the door, if he feels inclined. It is his affair. Strictly speaking, he should appreciate the delicacy of feeling which has gracefully left the performance of this simple act to his own discretion. Yes, it is in this fine instance of steady principle that we see a discrimination of politeness exquisitely ingenious and beautiful. The English have the reputation of being a blunt, downright people; and their practice of shutting the door after them makes it certain they are so. When they draw to the door, turn the handle, and hear the latch click, they as good as say: 'There, the door is shut; the thing is done. I leave no doubt on the subject; I care not what you think of me; I have done my duty.' This is England all over—great, uncalculating, independent-minded England! The Scotch almost pity this daring recklessness of character. They are astonished at its boldness. It is action resting on no proper grounds. How differently they proceed! Treating it as belonging to the science of numbers, the following becomes the method of stating the question:—

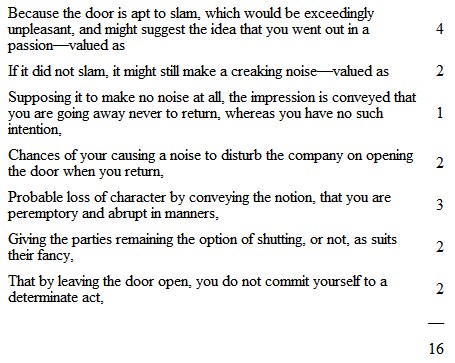

Given that there is a door which may or may not be shut on quitting an apartment, let it be shewn by the rules of arithmetic whether it would be preferable to shut the said door or leave it open. Write down, first, the arguments for not shutting, according to their supposed value; then do the same for the arguments per contra; lastly, sum up both, and strike the balance. Thus—

FOR NOT SHUTTING

Deducting 3 from 16, 13 remain. Result—balance of 13-19ths in favour of not shutting the door. Nothing, therefore, could be more clearly demonstrated than that the Scotch are strongly justified in leaving the door open when they quit an apartment. Doubts, indeed, may be entertained as to the values arbitrarily put on the respective items in the account: but to venture into this remote part of the inquiry would be to plunge us into the depths of metaphysics. Even supposing we were to make the matter as clear as the sun at noonday, there would still be sceptics. On shewing the above arithmetical calculation, for example, to an English lady, who has for a number of years studied Scotch character and manners, she, with a degree of bluntness that was exceedingly startling, gave it as her unqualified opinion, that the whole thing was a piece of nonsense; and that the only reason, as far as she could observe, why the Scotch do not shut the door, is that they have never been taught that it is consistent with good-manners to do so. The audacity of some people is really wonderful!

EDFOU AND ITS NEIGHBOURHOOD

There is something extremely pleasant in the general regularity with which the picture of Egypt unfolds itself on either hand like a double panorama as you descend the Nile. When moving in the opposite direction, against the perpetual current, you are sometimes compelled to creep slowly on, tugged by a tight-strained rope at the rate of seven or eight miles a day; whilst anon a wind rises unexpectedly, and carries you with bewildering speed through forty or fifty miles of scenery. But the masts being taken down, and the sails folded for the rest of the voyage, and the oars put out, you begin to calculate with tolerable certainty on the rate of progress; for though violent contrary winds do frequently blow during part of a day, it is almost always possible to make up for lost time in the hours that neighbour on sunset before and after. Well-seasoned Nile-travellers confirm our experience; and as we had rowed and floated within a calculated time from Assouan to Ombos, and from Ombos to Silsilis, so did we proceed to Edfou, and to the stations beyond, with few exceptions of obstinately adverse weather.

True, some portions of the view are missed during the hours of night-travelling; but these have most probably been seen during the ascent. Besides, though the scenery of the Nile is certainly not monotonous enough to weary the eye, yet there is a general sameness in its details, a want of those bold, original features which in other countries stamp the character of particular localities. Two parallel lines of mountains ever within sight of each other, now advancing towards the river through a sea of verdure in promontories, always nearly with the same level outline, now receding in semicircular sweeps; a narrow flat plain, loaded with crops and palm-groves, and intersected by canals and dikes, sometimes equally divided by a tortuous stream of vast breadth, but sometimes thrown, as it were, all to one side, east or west; occasionally a long line of precipices descending sheer into the very water; once only a regular defile with rocks on either hand; islands in the river, sandbanks, broad, winding reaches—such, in a few words, is a description of Egypt. It is the variety of colour produced by that mighty painter, the sun, that gives all the beauty to the landscape; and of this it is almost impossible to convey an idea. The chaste loveliness of the dawn, the majestic splendour of noon, and the marvellous glories of the sunset-hour—the thousand hues that glow and tremble, and melt and mingle around through all the scenes of this great drama of light—words have not yet been invented to describe.

And then the night! Who can sit down and recall and count over the impressions which fly like a troop of fairies over the thrilling senses at that mystic hour, when the skirts of retiring day have ceased to flutter above the western hills, and the moon casts down her pale, melancholy glances on the silent scene, and the stars—our guardian angels, according to some—seem to stoop nearer and nearer to the earth as slumber deepens, as if to press golden kisses upon the eyelids of those whom they watch and love! In all countries these hours are beautiful; but in Egypt—let those who doubt come and witness all that we beheld, and which is indescribable, on the evening that we left the neighbourhood of Silsilis on our way to Edfou—on that calm, placid river, over which brooded a silence interrupted only by the alternate songs of the crews of the two boats as they leisurely pulled with the current.

It was late in the afternoon of next day when we reached the landing-place; but we immediately set out to see the ruin, if ruin it can be called, for it is almost in perfect preservation. After traversing a broad extent of ground covered with rank grass and prickly plants, we came to the customary palm-grove, and then entered what romancers would probably call the 'good city' of Edfou. It is a considerable collection of huts, principally constructed of mud, clustering amidst mounds of rubbish at the base of the temple. The lofty propylæa, above a hundred feet high, I believe, were of course seen from afar off, both during our walk and in ascending and descending the river. As is the case in nearly all other Egyptian buildings, the effect at a distance is anything but picturesque. From want of objects of comparison, the impression of great size is not produced; and nothing can be meaner in outline than two towers like truncated pyramids, pierced with small, square windows at irregular intervals. On a nearer approach, however, the surface-ornament begins to appear; and the central doorway, overhung by a rich and painted cornice, presents itself in its really grand proportions, but crushed, as it were, by the vast size of the twin towers, which now seem magnified into mountains. At Edfou the effect of this surprise is partly injured by the circumstances: first, the accumulation of huts through which you approach; and second, that of mounds of dirt which have risen nearly to the height of the doorway. However, when you come to the summit of these mounds, almost on a level with the lintel, and look down between the enormous jambs into a kind of valley formed by the great court, with its wonderful portico and belt of columns, it is difficult to conceive a more imposing scene.

The walls on all sides were covered with gigantic figures, quite wonderful to behold in their serene ugliness; but awakening no more human sympathy than the singular figures we saw on the Chinese-patterned plate stuck over the doorway in Nubia. The exaggeration that is usually indulged in with reference to Egyptian art is such, that if we were to attempt to describe these sculptured ornaments according to our own impressions, we should run the risk of being accused of caricature. We do not mean on this temple only, but on all the temples of Egypt. Now and then a face of beautiful expression, though still with heavy features, is met with; but in general both countenance and figure are flat, out of proportion, and stiff in drawing, whilst the highest effort of colouring consists of one uniform layer, without tints or gradation. Perhaps amidst the many thousand subjects found in tombs and temples between Philœ and Cairo, one or two may be treated with nearly as much skill as was exhibited by the Italian painters before the time of Cimabue—except that scarcely an attempt even is made at grouping or composition. Nor must it be supposed that the Egyptian school was in course of development. They seem to have arrived at the highest excellence of which their intellect was capable. Their outlines, though in general excessively mean, are very firmly drawn; and they represent details with a laborious ingenuity worthy of the Chinese. Some enthusiastic antiquarians describe with great animation the scenes of public and domestic life which occur in such profusion; and, book in hand, we have admired and wondered at—not the genius of the artists, but that of their historians. How, in fact, do the Egyptians really proceed? They want to represent a hunt, for example: so they sketch a man with his legs extended like compasses, armed with a huge bow, from which he is in the act of discharging a monstrous arrow. Then close by they draw, without any attempt at perspective, a square enclosure, in which they set down higgledy-piggledy a variety of animals, some of them sufficiently like nature to allow their species to be guessed at. In one corner, perhaps, is a sprig of something intended for a tree, and intimating that all this is supposed to take place in a wood. This hieroglyphical or algebraical method of 'taking off' the occurrences of human life is applied with almost unvarying uniformity. Such was high art among the Egyptians; whom it is now the fashion to cry up at the expense of those impertinent Grecians, who presumed to arrive at excellence, almost at perfection, in so many departments.