полная версия

полная версияThe Naval Pioneers of Australia

Letters from the Home Office indicate that this was in a measure understood, but the tenor of the despatches also shows that it was thought the evils arose less from viciousness of the governed than from want of backbone in the governors.

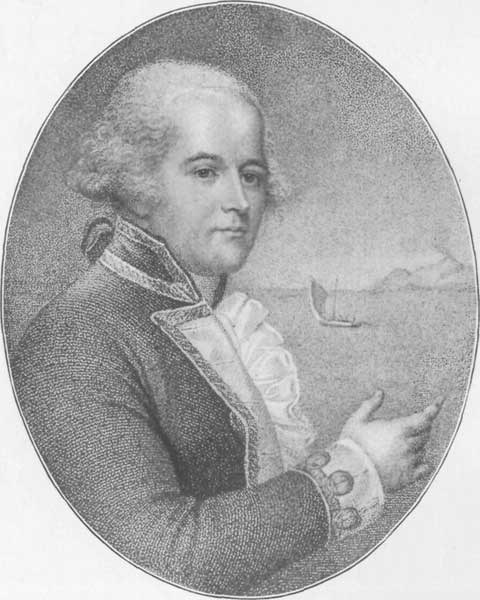

Bligh's character for courage and resolution may have led to his selection as a proper person to lick things into shape. It never seems to have occurred to his superiors that a man whose ship was taken from him by a dozen mutinous British seamen, if he were more forceful, resolute, tyrannical, what you will, than diplomatic in his methods, might lose a colony in which the colonists were not British sailors, but criminals and mutinous soldiers.

When Bligh landed, the principal agricultural settlements were on the banks of the rivers Hawkesbury and Nepean, and the settlers were just suffering from one of the most disastrous floods that have occurred in a country where floods are more severe than in most others. There was very little money in the colony, and the settlers carried on a legitimate system of barter by which they exchanged with each other their grain and herds. But the floods, of course, threw this system somewhat out of gear, and he who after the floods had escaped without much damage to his property had a pretty good pull upon his neighbour whose worldly belongings had been carried away by the swollen waters.

Bligh, there is no doubt, did the right thing at this time. He slaughtered a number of the Government cattle, dividing them among the more distressed colonists; and, to encourage them to go cheerfully to work to cultivate their land again and to become independent of their fellow-settlers, he promised to buy for the King's stores all the wheat they could dispose of after the next harvest, and to pay for it at a reasonable price.

Dr. Lang, in his History of New South Wales, published 1834 about 1834, relates how an old settler said to him, "Them were the days, sir, for the poor settler; he had only to tell the governor what he wanted, and he was sure to get it from the stores, whatever it was, from a needle to an anchor, from a penn'orth o' pack-thread to a ship's cable."

This arrangement was not conducive to the interests of the rum traders, who had been in the habit of purchasing grain and compelling the growers to accept spirits in payment for it. It operated still further against them when Bligh made a tour of the colony, took a note of each settler's requirements and of what the settler was likely to be able to produce from his land; then, according to what the governor thought the farmer was likely to be able to supply, Bligh gave an order for what was most needed by the man from the King's stores.

Of course this was taking a heavy responsibility upon himself. Even colonial governments nowadays, elected by "one-man-one-vote," scarcely go so far, but the state of the settlement must be remembered. There were no shops then, and the general public of the colony, with very few exceptions, was made up of Government officials and prisoners of the Crown. But the step was a serious interference with trade—that is, the rum trade; in consequence those in "the ring" were exasperated, and its members only wanted Bligh to give them an opportunity to retaliate upon and ruin him.

MacArthur, now a landed proprietor and merchant, soon after Bligh landed, paid him a visit, and reminded the new governor of an instruction sent to King that he (MacArthur) was to be given every encouragement in his endeavour to develop the pastoral resources of the colony. "Would Governor Bligh visit his estate on the Cowpasture river" (now Camden), "and see what had been done in this direction?" to which Governor Bligh, according to the report of Major Johnston's trial, replied, and with oaths: "What have I to do with your sheep and cattle? You have such flocks and herds as no man ever had before, and 10,000 acres of the best land in the country; but you shall not keep it." Here then was a declaration of war—MacArthur, too much of a trader to be a soldier, and politician enough to have enlisted on his side the English Government—which had announced its will that he should be encouraged as a valuable pioneer colonist—versus Bligh, so much of a warrior as to have fought beside Nelson with honour and so impolitic as to have lost his ship to a body of 1807 mutineers, some of them officers, of whose discontent, according to his own showing, he was unaware until the moment of the outbreak.

The fight began in this fashion. MacArthur had taken a promissory note from a man named Thompson. When the note became due, a fixed quantity of wheat was to be paid for its redemption; but, subsequent to the drawing of the note, came the great flood before mentioned; wheat went to ten times its former value, and MacArthur demanded payment on the higher scale. Thompson refused payment at the current rate, alleging that he was only bound to pay for grain at the rate he received it, although his crops had not suffered by the floods. The matter came before Bligh to decide, and he gave judgment against MacArthur, who forthwith ceased to visit Government House. Then MacArthur was taken ill, Bligh called upon him, and a peaceful aspect of affairs came over the land, which lasted until early in 1807.

Bligh, in accordance with his special instructions, had issued an order by which the distillation of spirits was prohibited, and the seizure of any apparatus employed in such process enjoined. Just about this time Captain Abbott, of the New South Wales Corps, had sent orders to his London agent to send him a still. MacArthur happened to employ the same agent, who thought it a good idea to also send his other patron a still.

In due time the two stills arrived, and were shown in the manifest of the ship that brought them. Bligh instructed the naval officer of the port to lodge them in the King's store, and send them back to England by the first returning ship. The still boilers were, however, packed full of medicine, and the naval officer, thinking no harm would come of it, allowed the boilers to go to MacArthur's house, lodging only the worms in the store. This happened in March. In the following October a ship was sailing for England, and the proper official set about putting the distilling apparatus on board of her, when he discovered that the coppers were still in the possession of MacArthur, who was asked to give them up. MacArthur replied that, with regard to one boiler, that was Captain Abbott's, who could do as he liked about it; but, with regard to the other, he (MacArthur) intended to send the apparatus to India or China, where it could be disposed of. However, if the governor thought proper, the governor could keep the worm and head of the still, and the copper he (MacArthur) intended to apply to domestic purposes. The 1808 governor thereupon, after the exchange of numerous letters between MacArthur and himself, caused the stills complete to be seized; and then MacArthur brought an action for an alleged illegal seizure of his property.

MacArthur was right enough on one detail of this dispute. Bligh had demanded that he should accept from an official a receipt for "two stills with worms and heads complete." As MacArthur had never had in his possession anything but two copper boilers, he naturally refused to commit himself in this fashion, and would only accept a receipt for the coppers. The naval officer accordingly took the coppers, and MacArthur took no receipt for them.

Then happened a more serious affair. MacArthur partly owned a schooner which was employed trading to Tahiti; in this vessel a convict had stowed away, and the master of the vessel had left him at the island. The missionaries wrote to Bligh complaining of this, and proceedings were begun against MacArthur by the Government to recover the penalty incurred under the settlement regulations for carrying away a prisoner of the Crown, and a bond of £900, which had been given by the owners of the vessel, was declared forfeit.

MacArthur appealed from the court to Bligh, and Bligh upheld the court's decision. MacArthur and his partners still refused to pay, and the court officials seized the vessel. MacArthur promptly announced that her owners had abandoned her, and the crew, having no masters, walked ashore. For sailors to remain ashore in a penal settlement was another breach of regulations, chargeable against the owners of the ship from which the sailors landed, provided the sailors had left the ship with the consent of the owners; and the sailors declared that the owners had ordered them to leave the schooner.

MacArthur was summoned to attend the Judge-Advocate's office to "show cause." He refused to come, on the ground that the vessel was not his property, but now belonged to the Government. One Francis Oakes, an ex-Tahitian missionary, who, having disagreed with his colleagues in the islands, had turned constable, was then given a warrant to bring MacArthur from his house at Parramatta to Sydney. Oakes came back and reported that MacArthur refused to submit, and had threatened that if he (Oakes) came a second time he had better come well armed; and much more to the same purpose. Accordingly certain well-armed civil officials 1808 went back and executed the warrant, and MacArthur was brought before a bench of magistrates, over whom Atkins, the Judge-Advocate, presided, and was committed for trial.

Atkins did not know anything of law, but he had as legal adviser an attorney who had been transported, and whose character, Bligh himself said, was that of an untrustworthy, ignorant drunkard.

The court opened on January 25th, 1808. It was formed from six officers of the New South Wales Corps, presided over by the Judge-Advocate, and the court-house was crowded with soldiers of the regiment, wearing their side arms. The indictment charged MacArthur with the contravention of the governor's express orders in detaining two stills; with the offence of inducing the crew of his vessel to leave her and come on shore, in direct violation of the regulations; and with seditious words and an intent to raise dissatisfaction and discontent in the colony by his speeches to the Crown officials and by a speech he had made in the court of inquiry over the seizure of the stills. The speech complained of was to the following effect:—

"It would therefore appear that a British subject in a British settlement, in which the British laws are established by the royal patent, has had his property wrested from him by a non-accredited individual, without any authority being produced or any other reason being assigned than that it was the governor's order; it is therefore for you, gentlemen, to determine whether this be the tenure by which Englishmen hold their property in New South Wales."

MacArthur objected in a letter to Bligh, written before the trial, to the Judge-Advocate presiding, on the ground that this official was really a prosecutor, and had animus against him. Bligh overruled the objection, on the ground that the Criminal Court of the colony, by the terms of the King's patent, could not be constituted without the Judge-Advocate. MacArthur renewed his objection when the court met; Captain Kemp, one of the officers sitting as a member of the court, supported MacArthur's view; and the Judge-Advocate was compelled to leave his seat as president.

MacArthur then made a speech, in which he denounced the Judge-Advocate in very strong language, and that official called out from the back of the court that he would commit MacArthur for his conduct. Then Captain Kemp told the Judge-Advocate to be silent, and threatened 1808 to send him to gaol, whereupon Atkins ordered that the court should adjourn, but Kemp ordered it to continue sitting. The Judge-Advocate then left the court, and MacArthur called out: "Am I to be cast forth to the mercy of these ruffians?"—meaning the civil police—and added that he had received private information from his friends that he was to be attacked and ill-treated by the civilians; whereupon the military officers undertook his protection and told the soldiers in the court to escort him to the guard-room.

Then the Provost-Marshal said this was an attempt to rescue his prisoner, went at once and swore an affidavit to this effect before Judge-Advocate Atkins and three other justices of the peace, and procured their warrant for the arrest of MacArthur. This was shown to the military officers; they surrendered MacArthur, who was lodged in the gaol. The court broke up, and the officers then wrote to Bligh, accusing the Provost-Marshal of perjury in stating that they contemplated a rescue.

This business had lasted from the opening of the court in the morning until two o'clock in the afternoon.

Bligh, in accordance with his legal right, had all along refused to interfere with the constitution of the court. At the same time, there was no doubt that MacArthur could not have a fair trial if Judge-Advocate Atkins was to try him, for it was notorious that the two men had been at enmity for several years. Bligh demanded all the papers in the case from the officers, who, in his opinion, had illegally formed themselves into a court. They refused to give them up unless the governor appointed a new Judge-Advocate, and Bligh replied with a final demand that they should obey or refuse in writing. Then he wrote to Major Johnston, who commanded the regiment, and who lived some distance from Sydney, to come into town at once, as he wanted to see him over the "peculiar circumstances." Johnston sent a verbal message to the effect that he was too ill to come, or even to write. This was mere trickery.

The next morning, January 26th (the anniversary of the founding of the colony), the officers assembled in the court-room, and as no prisoner was forthcoming for them to try, they wrote a protest to the governor, in which they set forth that, having been sworn in to try MacArthur, they conceived they could not break up the court until he was tried; that the accused had been arrested and removed from the court; 1808 and that, in effect, the sooner the governor appointed a new Judge-Advocate the better for all parties.

No notice was taken of this letter, but Bligh issued a summons to the officers to appear before him at Government House to answer for their conduct, and at the same time he wrote a second letter to Johnston, asking him to come to town, and got a second reply from that officer, to the effect that he was still too ill. But he was well enough to continue plotting against Bligh.

Soon after sending this second letter Johnston rode into town, arriving at the barracks at five o'clock in the evening. He held a consultation with his officers, and the upshot of this was that Johnston, as lieutenant-governor of the colony, demanded the instant release of MacArthur from gaol. The gaoler complied, and MacArthur went straight to the barracks, where a requisition to Johnston to place Bligh under arrest was arranged, at the suggestion of MacArthur, on the ground "that the present alarming state of the colony, in which every man's property, liberty, and life are endangered, induces us most earnestly to implore you instantly to assume the command of the colony. We pledge ourselves at a moment of less agitation to come forward to support the measure with our lives and fortunes." This was signed by several of the principal Sydney inhabitants, and then Johnston proceeded to carry out their and his own and the other rum-traffickers' designs.

The drums beat to arms; the New South Wales Corps—most of the men primed with the original cause of the trouble—formed in the barrack square, and with fixed bayonets, colours flying, and band playing, marched to Government House, led by Johnston. It was about half-past six on an Australian summer evening, and broad daylight. The Government House guard waited to prime and load, then joined their drunken comrades, and the house was surrounded.

Mrs. Putland, the governor's brave daughter (widow of a lieutenant in the navy, who had only been buried a week before), stood at the door, and endeavoured to prevent the soldiers from entering. She was pushed aside, and the house was soon full of soldiers, who, according to what some of them said, found Bligh hiding under his bed—a statement which, there is not the slightest doubt, was an infamous lie, suggested by the position in which the governor really was found, viz., standing behind a cot in a back room, where he was endeavouring to conceal some 1808 private papers.

Bligh surrendered to Johnston, who announced that he intended to assume the government "by the advice of all my officers and the most respectable of the inhabitants." Johnston caused Bligh's commission and all his papers to be sealed up, informed the governor that he would be kept a prisoner in his own house, and leaving a strong guard of soldiers, marched the rest of his inebriated command back to barracks, with the same parade of band-playing and pretence of dignity.

The colony was now practically under martial law, and Johnston appointed a new batch of civil officials, dismissing from office the others, including the Judge-Advocate, Atkins. MacArthur was then—humorously enough—tried by the court as newly constructed, and, of course, unanimously acquitted, Johnston then appointing him a magistrate and secretary of the colony. To complete the business, the court then took it upon themselves to try the Provost-Marshal, and gave him four months' gaol for having "falsely sworn that the officers of the New South Wales Corps intended to rescue his prisoner" (MacArthur), and at the same time the court sentenced the attorney who drew the indictment, and managed the legal business for Atkins, to a long term of imprisonment.

In July, Lieutenant-Colonel Foveaux arrived from England, and was surprised to find the existing state of affairs. By virtue of seniority, he succeeded Johnston as lieutenant-governor, and appointed another man in place of MacArthur, but did not interfere in any other way, contenting himself with sending to England a full report of the affair. Foveaux was in turn succeeded by Colonel Paterson, who arrived at the beginning of 1809, and who also declined to interfere in the business, but he granted Johnston leave of absence to proceed to England, MacArthur and two other officers accompanying him.

Meanwhile some of the free settlers had begun to show indications of a desire to help Bligh, who, to prevent accidents, was taken by the rebels from his house and lodged with his daughter a close prisoner in the barracks. Later on, he signed an agreement with Paterson to leave the colony for England in a sloop of war then bound home.

Bligh and his daughter embarked on the vessel, but on the way she put into the Derwent river, in Van Diemen's Land, where the 1809 deposed governor landed, and at first thought he would be able to re-establish his authority, but the spirit of rebellion had taken hold; he was compelled to re-embark soon after, but he remained in Tasmanian waters on board ship until Governor Macquarie arrived from England.

For the English Government, in due course, had heard of the state of affairs, and woke up to the necessity for strong action. In December, 1809, there arrived in Sydney Harbour a 50-gun frigate and a transport, bringing Governor Macquarie, with his regiment of Highlanders, the 73rd. His orders were to restore Bligh for twenty-four hours and send home the New South Wales Corps, with every officer who had been concerned in the rebellion under arrest, and the regiment, as we said in a former chapter, was disbanded; Macquarie was himself then to take over the government.

The absence of Bligh from the colony prevented his restoration being literally carried out, but Macquarie issued proclamations which served the purpose, and restored all the officials who had been put out by the rebels. Macquarie soon made himself popular with the colonists, and the best proof of his success is the fact that he governed the colony for twelve years, and his administration, though an important epoch in its history, cannot be gone into here as he was not a naval man.

Bligh, the last of the naval governors, arrived in England in October, was made a rear-admiral, and died in 1817. Johnston was tried by court-martial and cashiered, and returned to the colony, becoming one of its best settlers and the founder of one of Sydney's most important suburbs. MacArthur was ordered not to return to the colony for eight years. He returned in 1817, bringing with him sons as vigorous as himself. Ultimately he became a member of the Legislative Council, and his services and those of his descendants will justly be remembered in Australia long after the petty annoyances to which he was subjected and the improper manner in which he resisted them have been totally and happily forgotten.

The history of Australia up to, and until the end of Bligh's appointment, can be summed up in half a dozen sentences. Phillip, during the term of his office, had repeatedly urged upon the home Government the necessity of sending out free men. Convicts without such a leaven could not, in his opinion, successfully lay the foundation of the "greatest acquisition England has ever made." Time proved the correctness of his judgment. The population of the colony, from something more than 1000 when he landed, had been increased at the close of King's administration to about 7000 persons. Half a dozen settlements had been formed at places within a few miles of Sydney; advantage had been taken of the discoveries of Bass and Flinders, and settlements made at Hobart and at Port Dalrymple; while an attempt (resulting in failure on this occasion and described later on) was made to colonize Port Phillip. A good deal of country was under cultivation, and stock had greatly increased, so that in the seventeen years that had elapsed some progress had been made, but the state of society at Botany Bay had grown worse rather than better. In the direction of reformation the experiment of turning felons into farmers was not a success. Few free emigrants had arrived in the colony, and those who came out were by no means the best class of people. Nobody worked more than they could help; drinking, gambling, and petty bickering occupied the leisure of most. This was the state of affairs which Captain Bligh was sent to reform, and we have seen how his mission succeeded.

In the case of the mutiny of the Bounty, it is reasonably believed that the mutineers were, at any rate, partially incited to their crime by the seductions of Tahiti; in the case of the revolt in New South Wales, it is known that allegiance to constituted authority had no part in the character of Bligh's subjects. Therefore, notwithstanding that Bligh was the victim of two outbreaks against his rule, posterity, without the most indisputable evidence to the contrary, would have held him acquitted of the least responsibility for his misfortunes. In the case of the Bounty mutiny the evidence of Bligh's opponents that the captain of the Bounty was a tyrannical officer remains uncontradicted by any authority but that of the Bounty's captain; in the case of the New South Wales revolt we can only judge of the probabilities, for the witnesses at the Johnston court-martial were of necessity upon one side. But the court-martial, a tribunal not at all likely to err upon the side of mutineers, came to the same conclusion as we have, and, so far as we are aware, most other writers acquainted with the subject have been driven to: that Bligh, to say the least of it, behaved with great indiscretion.

Our references to this matter have been entirely to 1829 the minutes of the court-martial and to writers who wrote long enough ago to have had a personal knowledge of the subject or acquaintance with actors in the events. The lady whose letter we have quoted in the first pages of this chapter refers us to Lang's History for a justification of Bligh, and Dr. Lang, as is well known to students of Australian history, wrote more strongly in that governor's favour than did any other writer. Dr. Lang tells us that the behaviour of certain subordinates towards MacArthur was highly improper, and that MacArthur's speech in open court was "calculated to give great offence to a man of so exceedingly irritable disposition as Governor Bligh." Again, Dr. Lang says that Bligh by no means merited unqualified commendation for his government of New South Wales, and that the truth lies between the most unqualified praise and the most unqualified vituperation which the two sides of this quarrel have loaded upon his memory.