полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Volume 54, No. 333, July 1843

"But truly, as I had to remark in the meanwhile, the 'liberty of not being oppressed by your fellow-man,' is an indispensable, yet one of the most insignificant fractional parts of human liberty. No man oppresses thee—can bid thee fetch or carry, come or go, without reason shown. True; from all men thou art emancipated, but from thyself and from the devil! No man, wiser, unwiser, can make thee come or go; but thy own futilities, bewilderments, thy false appetites for money—Windsor Georges and such like! No man oppresses thee, O free and independent Franchiser! but does not this stupid porter-pot oppress thee? no son of Adam can bid thee come and go; but this absurd pot of heavy-wet, this can and does! Thou art the thrall, not of Cedric the Saxon, but of thy own brutal appetites, and this scoured dish of liquor; and thou protest of thy 'liberty,' thou entire blockhead!"—P. 292.

We should hardly think of entering with Mr Carlyle into a controversy upon the corn-laws, or on schemes of emigration, or any disputed point of political economy. He brings to bear upon these certain primitive moral views and feelings which are but very remotely applicable in the resolution of these knotty problems. We should almost as soon think of inviting the veritable Diogenes himself, should he roll up in his tub to our door, to a discussion upon our commercial system. Our Diogenes Teufelsdrockh looks upon these matters in a quite peculiar manner; observe, for example, the glance he takes at our present mercantile difficulties, which, doubtless, is not without its own value, nor undeserving of all consideration.

"The continental people, it would seem, are 'exporting our machinery, beginning to spin cotton, and manufacture for themselves, to cut us out of this market and then out of that!' Sad news, indeed, but irremediable—by no means the saddest news. The saddest news is, that we should find our national existence, as I sometimes hear it said, depend on selling manufactured cotton at a farthing an ell cheaper than any other people—a most narrow stand for a great nation to base itself on; a stand which, with all the corn-law abrogations conceivable, I do not think will be capable of enduring.

"My friends, suppose we quitted that stand; suppose we came honestly down from it, and said—'This is our minimum of cotton prices; we care not, for the present, to make cotton any cheaper. Do you, if it seems so blessed to you, make cotton cheaper. Fill your lungs with cotton fug, your hearts with copperas fumes, with rage and mutiny; become ye the general gnomes of Europe, slaves of the lamp!' I admire a nation which fancies it will die if it do not undersell all other nations to the end of the world. Brothers, we will cease to undersell them; we will be content to equalsell them: to be happy selling equally with them. I do not see the use of underselling them; cotton cloth is already twopence a yard or lower, and yet bare backs were never more numerous amongst us. Let inventive men cease to spend their existence incessantly contriving how cotton can be made cheaper; and try to invent, a little, how cotton, at its present cheapness, could be somewhat juster divided amongst us! Let inventive men consider whether the secret of this universe, and of man's life there, does after all, as we rashly fancy it, consist in making money? There is one God—just, supreme, almighty: but is Mammon the name of him?

"But what is to be done with our manufacturing population, with our agricultural, with our ever-increasing population?—cry many.—Ay, what? Many things can be done with them, a hundred things, a thousand things—had we once got a soul and begun to try. This one thing of doing for them by 'underselling all people,' and filling our own bursten pockets by the road; and turning over all care for any 'population,' or human or divine consideration, except cash only, to the winds, with a 'Laissez-faire' and the rest of it; this is evidently not the thing. 'Farthing cheaper per yard;' no great nation can stand on the apex of such a pyramid; screwing itself higher and higher: balancing itself on its great toe! Can England not subsist without being above all people in working? England never deliberately proposed such a thing. If England work better than all people, it shall be well. England, like an honest worker, will work as well as she can; and hope the gods may allow her to live on that basis. Laissez-faire and much else being once dead, how many 'impossibles' will become possible! They are 'impossible' as cotton-cloth at twopence an ell was—till men set about making it. The inventive genius of great England will not for ever sit patient with mere wheels and pinions, bobbins, straps, and billy-rollers whirring in the head of it. The inventive genius of England is not a beaver's, or a spinner's, or a spider's genius: it is a man's genius, I hope, with a God over him!"—P. 246.

And hear our Diogenes on the often repeated cry of over-production:—

"But what will reflective readers say of a governing class, such as ours, addressing its workers with an indictment of 'over-production!' Over-production: runs it not so? 'Ye miscellaneous ignoble, manufacturing individuals, ye have produced too much. We accuse you of making above two hundred thousand shirts for the bare backs of mankind. Your trousers too, which you have made of fustian, of cassimere, of Scotch plaid, of jane, nankeen, and woollen broadcloth, are they not manifold? Of hats for the human head, of shoes for the human foot, of stools to sit on, spoons to eat with—Nay, what say we of hats and shoes? You produce gold watches, jewelleries, silver forks and épergnes, commodes, chiffoniers, stuffed sofas—Heavens, the Commercial Bazar and multitudinous Howel and James cannot contain you! You have produced, produced;—he that seeks your indictment, let him look around. Millions of shirts and empty pairs of breeches hang there in judgment against you. We accuse you of over-producing; you are criminally guilty of producing shirts, breeches, hats, shoes, and commodities in a frightful over-abundance. And now there is a glut, and your operatives cannot be fed.'

"Never, surely, against an earnest working mammonism was there brought by game-preserving aristocratic dilettantism, a stranger accusation since this world began. My Lords and Gentlemen—why it was you that were appointed, by the fact and by the theory of your position on the earth, to make and administer laws. That is to say, in a world such as ours, to guard against 'gluts,' against honest operatives who had done their work remaining unfed! I say, you were appointed to preside over the distribution and appointment of the wages of work done; and to see well that there went no labourer without his hire, were it of money coins, were it of hemp gallows-ropes: that formation was yours, and from immemorial time has been yours, and as yet no other's. These poor shirt-spinners have forgotten much, which by the virtual unwritten law of their position they should have remembered; but by any written recognized law of their position, what have they forgotten? They were set to make shirts. The community, with all its voices commanded them, saying, 'make shirts;'—and there the shirts are! Too many shirts? Well, that is a novelty, in this intemperate earth, with its nine hundred millions of bare backs! But the community commanded you, saying, 'See that the shirts are well apportioned, that our human laws be emblems of God's law;' and where is the apportionment? Two millions shirt-less, or ill-shirted workers sit enchanted in work-house Bastiles, five millions more (according to some) in Ugoline hunger-cellars; and for remedy, you say—what say you? 'Raise our rents!' I have not in my time heard any stranger speech, not even on the shores of the Dead Sea. You continue addressing these poor shirt-spinners and over-producers in really a too triumphant manner.

"Will you bandy accusations, will you accuse us of over-production? We take the heavens and the earth to witness, that we have produced nothing at all. Not from us proceeds this frightful overplus of shirts. In the wide domains of created nature, circulates nothing of our producing. Certain fox-brushes nailed upon our stable-door, the fruit of fair audacity at Melton Mowbray; these we have produced, and they are openly nailed up there. He that accuses us of producing, let him show himself, let him name what and when. We are innocent of producing,—ye ungrateful, what mountains of things have we not, on the contrary, had to consume, and make away with! Mountains of those your heaped manufactures, wheresoever edible or wearable, have they not disappeared before us, as if we had the talent of ostriches, of cormorants, and a kind of divine faculty to eat? Ye ungrateful!—and did you not grow under the shadow of our wings? Are not your filthy mills built on these fields of ours; on this soil of England, which belongs to—whom think you? And we shall not offer you our own wheat at the price that pleases us, but that partly pleases you? A precious notion! What would become of you, if we chose at any time to decide on growing no wheat more?"

An amusing—caustic—exaggeration, more like a portion of a clever satire on man and society, than a sincere discussion of political evils and remedies; and not intended, we trust, for Mr Carlyle's own sake, to express his real belief in the true causes of the evils of society. If we could suppose that this piece of extravagant and one-sided invective were meant to be seriously taken, as embodying Mr Carlyle's social and political creed, we should scarcely find words strong enough to reprobate its false and mischievous tendency.

We have already said, that we regard the chief value of Mr Carlyle's writings to consist in the tone of mind which the individual reader acquires from their perusal;—manly, energetic, enduring, with high resolves and self-forgetting effort; and we here again, at the close of our paper, revert to this remark: Past and Present, has not, and could not have, the same wild power which Sartor Resartus possessed, in our opinion, over the feelings of the reader; but it contains passages which look the same way, and breathe the same spirit. We will quote one or two of these, and then conclude our notice. Their effect will not be injured, we may observe, by our brief manner of quotation. Speaking of "the man who goes about pothering and uproaring for his happiness," he says:—

"Observe, too, that this is all a modern affair; belongs not to the old heroic times, but to these dastard new times. 'Happiness, our being's end and aim,' is at bottom, if we will count well, not yet two centuries old in the world. The only happiness a brave man ever troubled himself with asking much about was, happiness enough to get his work done. Not, 'I can't eat!' but, 'I can't work!' that was the burden of all wise complaining among men. It is, after all, the one unhappiness of a man—that he cannot work—that he cannot get his destiny as a man fulfilled."

"The latest Gospel in this world, is, know thy work and do it. 'Know thyself;' long enough has that poor 'self' of thine tormented thee; thou wilt never get to 'know' it, I believe! Think it not thy business, this of knowing thyself; thou art an unknowable individual; know what thou canst work at; and work at it like a Hercules! That will be thy better plan."

"Blessed is he who has found his work; let him ask no other blessedness. He has a work, a life-purpose; he has found it, and will follow it! How, as a free-flowing channel, dug and torn by noble force through the sour mud-swamp of one's existence, like an ever-deepening river, there it runs and flows;—draining off the sour festering water gradually from the root of the remotest glass-blade; making, instead of pestilential swamp, a green fruitful meadow with its clear-flowing stream. How blessed for the meadow itself, let the stream and its value be great or small. Labour is life!"

"Who art thou that complainest of thy life of toil? Complain not. Look up, my wearied brother; see thy fellow workmen there, in God's eternity—surviving there—they alone surviving—sacred band of the Immortals. Even in the weak human memory they survive so long as saints, as heroes, as gods; they alone surviving—peopling, they alone, the immeasured solitudes of time! To thee, Heaven, though severe, is not unkind. Heaven is kind, as a noble mother—as that Spartan mother, saying, as she gave her son his shield, 'with it, my son, or upon it!'

"And, who art thou that braggest of thy life of idleness; complacently showest thy bright gilt equipages; sumptuous cushions; appliances for the folding of the hands to more sleep? Looking up, looking down, around, behind, or before, discernest thou, if it be not in Mayfair alone, any idle hero, saint, god, or even devil? Not a vestige of one. 'In the heavens, in the earth, in the waters under the earth, is none like unto thee.' Thou art an original figure in this creation, a denizen in Mayfair alone. One monster there is in the world: the idle man. What is his 'religion?' That nature is a phantasm, where cunning, beggary, or thievery, may sometimes find good victual."

"The 'wages' of every noble work do yet lie in heaven, or else nowhere. Nay, at bottom dost thou need any reward? Was it thy aim and life-purpose, to be filled with good things for thy heroism; to have a life of pomp and ease, and be what men call 'happy' in this world, or in any other world? I answer for thee, deliberately, no?

"The brave man has to give his life away. Give it, I advise thee—thou dost not expect to sell thy life in an adequate manner? What price, for example, would content thee?... Thou wilt never sell thy life, or any part of thy life, in a satisfactory manner. Give it, like a royal heart—let the price be nothing; thou hast then, in a certain sense, got all for it!"

Well said! we again repeat, O Diogenes Teufelsdrockh!

Edinburgh: Printed by Ballantyne and Hughes, Paul's Work1

No. cccxxvii, p. 137.

2

No. cccxxvii. p. 130.

3

"Return with it or upon it" was the well-known injunction of a Greek mother, as she handed her son his shield previous to the fight.

4

The mummy-wheat.

5

An introduction, prefixed to Holinshed, descriptive of domestic life amongst the English, as it may be presumed to have existed for the century before, (1450-1550,) was written (according to our recollection) by Harrison. Almost a century earlier, we have Chief Justice Fortescue's account of the French peasantry, a record per antiphrasin of the English. About the great era of 1688, we have the sketch of contemporary English civilization by Chamberlayne. So rare and distant are the glimpses which we obtain of ourselves at different periods.

6

To say the truth, during the Marlborough war of the Succession, and precisely one hundred years before Murat's bloody occupation of Madrid, Spain presented the same infamous spectacle as under Napoleon; armies of strangers, English, French, Germans, marching, and counter-marching incessantly, peremptorily disposing of the Spanish crown, alternately placing rival kings upon the throne, and all the while no more deferring to a Spanish will than to the yelping of village curs.

7

It may be thought, indeed, that as a resident in Holland, Salmasius should have had a glimpse of the new truth; and certainly it is singular that he did not perceive the rebound, upon his Dutch protectors, of many amongst his own virulent passages against the English; unless he fancied some special privilege for Dutch rebellion. But in fact he did so. There was a notion in great currency at the time—that any state whatever was eternally pledged and committed to the original holdings of its settlement. Whatever had been its earliest tenure, that tenure continued to be binding through all ages. An elective kingdom had thus some indirect means for controlling its sovereign. A republic was a nuisance, perhaps, but protected by prescription. And in this way even France had authorized means, through old usages of courts or incorporations, for limiting the royal authority as to certain known trifles. With respect to the Netherlands, the king of Spain had never held absolute power in those provinces. All these were privileged cases for resistance. But England was held to be a regal despotism.

8

And, in reality, this impression, as from some high-bred courtesy and self-restraint, is likely enough to arise at first in every man's mind. But the true ground of the amiable features was laid for the Roman in the counter-force of exquisite brutality. Where the style of public intercourse had been so deformed by ruffianism, in private intercourse it happened, both as a natural consequence, and as a difference sought after by prudence, that the tendencies to such rough play incident to all polemic conversation (as in the De Oratore) should be precluded by a marked extremity of refined pleasure. Hence indeed it is, that compliments, and something like mutual adulation, prevail so much in the imaginary colloquies of Roman statesmen. The personal flatteries interchanged in the De Oratore, De Legibus, &c., of Cicero, are often so elegantly turned, and introduced so artfully, that they read very much like the high bred compliments ascribed to Louis XIV., in his intercourse with eminent public officers. These have generally a regal air of loftiness about them, and prove the possibility of genius attaching even to the art of paying compliments. But else, in reviewing the spirit of traffic, which appears in the reciprocal flatteries passing between Crassus, Antony, Cotta, &c., too often a sullen suspicion crosses the mind of a politic sycophancy, adopted on both sides as a defensive armour.

9

In the days of Gottsched, a German leader about 1740, who was a pedant constitutionally insensible to any real merits of French literature, and yet sharing in the Gallomania, the ordinary tenor of composition was such as this: (supposing English words substituted for German:) "I demande with entire empressement, your pardon for having tant soit peu méconnu, or at least egaré from your orders, autrefois communicated. Faute d'entendre your ultimate but, I now confess, de me trouver perplexed by un mauvais embarras."—And so on.

10

A successful salmon-fly so named.

11

See Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Vol. XV. Part iii. p. 343.

12

Certain river mouths and estuaries in the north of Scotland "within flude-marke of the sea," have lately given rise to various questions of disputed rights regarding the erection of stake-nets, and the privilege of catching salmon with the same. These questions involve the determination of several curious though somewhat contradictory points in physical geography, geology, and the natural history of fishes and marine vegetation.

13

The following curious particulars regarding the above-mentioned salmon are taken from a Devonshire newspaper:—"She would come to the top of the water and take meat off a plate, and would devour a quarter of a pound of lean meat in less time than a man could eat it; she would also allow Mr Dormer to take her out of the water, and when put into it again she would immediately take meat from his hands, or would even bite the finger if presented to her. Some time since a little girl teased her by presenting the finger and then withdrawing it, till at last she leaped a considerable height above the water, and caught her by the said finger, which made it bleed profusely: by this leap she threw herself completely out of the water into the court. At one time a young duckling got into the well, to solace himself in his favourite element, when she immediately seized him by the leg, and took him under water; but the timely interference of Mr Dormer prevented any further mischief than making a cripple of the young duck. At another time a full-grown drake approached the well, when Mrs Fish, seeing a trespasser on her premises, immediately seized the intruder by the bill, and a desperate struggle ensued, which at last ended in the release of Mr Drake from the grasp of Mrs Fish, and no sooner freed, than Mr Drake flew off in the greatest consternation and affright; since which time, to this day, he has not been seen to approach the well, and it is with great difficulty he can be brought within sight of it. This fish lay in a dormant state for five months in the year, during which time she would eat nothing, and was likewise very shy."

14

The net fishings in the Tweed do not close till the 16th of October, and the lovers of the angle are allowed an additional fortnight. These fishings do not open (either for net or rod) till the 15th of February.

15

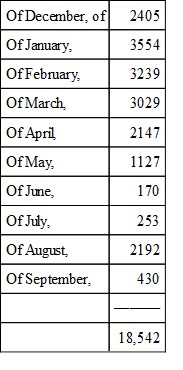

It was proved in evidence before the select committee of the House of Commons in 1825, that the amount of salmon killed in the Ness during eight years, (from 1811-12 to 1818-19,) made a total for the months

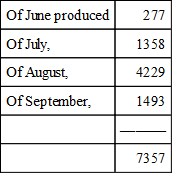

It further appears, from the evidence referred to, that during these years no grilse ran up the Ness till after the month of May. The months

16

See Mr Shaw's paper "On the Growth and Migration of the Sea-trout of the Solway."—Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Vol. XV. Part iii. p. 369.

17

The Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart., by his literary executor.

18

In the quadrangle of Brazenose College, there is a statue of Cain destroying Abel with a bone, or some such instrument. It is of lead, and white-washed, and no doubt that those who have heard that Cain was struck black, will be surprised to find that in Brazenose he is white as innocence.

19

All the world has rung with the fame of Roger Bacon, formerly of this college, and of his exploits in astrology, chemistry, and metallurgy, inter alia his brazen head, of which alone the nose remains, a precious relic, and (to use the words of the excellent author of the Oxford Guide) still conspicuous over the portal, where it erects itself as a symbolical illustration of the Salernian adage "Noscitur a naso."

20

Two medallions of Alfred and Erigena ornament the outside of the Hall, so as to overlook the field of battle.

21

The Porter of the college.

22

The doctor's servant or scout.

23

Two wine-merchants residing in Oxford.

24

To those gentlemen who, for half an hour together, have sometimes had the honour of waiting in the Doctor's antechamber, "Donec libeat vigilare tyranno," this passage will need no explanation; and of his acts of graceful dignity and unaffected piety at chapel, perhaps the less that is said the better.