Полная версия

The Amphibian / Человек-амфибия. Книга для чтения на английском языке

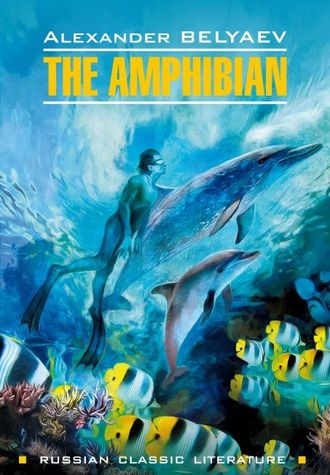

A cry of surprise escaped the divers.

The creature looked round. The next they knew it was off the dolphin and on the other side of it. A green foreleg shot into sight to slap the dolphin’s back. Obedient to it the mount submerged.

The odd pair could just be seen making a quick half-circle and then it disappeared behind the reefs.

The whole thing had taken not more than a minute but the lookers-on stood rooted to the spot for some time.

Then hell broke loose. Some of the Indians shouted and ran about as though demented, others fell on their knees and prayed to God to spare their lives. A young Mexican, bawling with fright, took refuge high up the main mast. The Blacks crept below into the hold.

There could be no question of going on with the work. It was all Pedro and Bal-tasar. could do to restore some order. The Jellyfish weighed anchor and sailed due north.

Zurita’s Ill Luck

The master of the vessel went below, to his cabin, to think things over. It’s enough to drive one mad! he thought, pouring tepid water from a jug over his head. A sea-monster speaking the purest Castellano! What was it? The Devil’s work? Hallutination? Can’t happen to whole crews though. No two men even see the same dream. But we all saw the thing. That’s a fact. So the “sea-devil” does exist after all-however impossible it may sound. Zurita poured more water over his head and leaned out of the port-hole for some fresh air.

“Sea-devil” or not, he thought on, calming a bit, the monster appears to possess intelligence and an excellent command of Spanish. You should be able to talk to it. Suppose-Yes, why not? Suppose I catch it and make it dive for pearls. Why, a creature like that would be worth a whole shipful of divers. I’d be simply minting money! Every diver must have his fourth of the catch but this thing here’d only cost me its keep. That’d mean thousands, millions of pesos rolling in.

Zurita glowed with his vision of wealth. Not that it was the first time he had had it. Time and again he had dreamt of finding new, still untapped, pearling grounds. The Persian Gulf, the western coast of Ceylon, the Red Sea and the coasts of Australia were far too distant for him and pretty well fished clean at that. Even the Gulf of Mexico, the Gulf of California and the coast of Venezuela, where the best American pearls were found, were too remote for his ancient schooner. He’d need more divers too. And Zurita had no money for that. So he kept in home waters. But now it was different. Now he could make his pile-once he had the “sea-devil” in his hands.

He’d be the richest man in Argentina, perhaps in both Americas. Money would pave his way to power. His name would sweep the world… But he had to play his hand careful like-and first see to it that the crew didn’t talk.

Zurita went on deck and had the whole crew down to the cook called up.

“You all know,” he told them, “what happened to those who had been spreading rumours about the ‘sea-devil’. If you don’t they’re still in jail. Let me give you a word of warning. This is it: anyone of you caught speaking of having seen the ‘sea-devil’ will be clapped in jail to feed vermin. Got that? So keep it under your hats unless you want to get into trouble.”

Nobody’d believe them anyway, not a fairy-tale like that, Zurita thought, and, telling Baltasar to follow him, went below.

Baltasar listened to Zurita’s plan in silence.

“Sounds good,” he said after a moment’s thought. “The creature’s worth a hundred divers. A ‘devil’ at your beck and call-not bad, eh? But you’ve got to catch it first.”

“A sturdy net’ll take care of that,” said Zurita.

“He’ll rip a net open as easily as he ripped that shark’s belly.”

“We can order a wire net.”

“Who’s going to do the catching? Not our divers. There’s not one in the whole lot of ‘em won’t turn yellow at the mere name of it. They wouldn’t dream of giving a hand, not for all the riches in the world.”

“What about you, Baltasar?”

The Indian shrugged his shoulders.

“I’ve never hunted a ‘sea-devil’. I expect it’ll be no easy thing stalking him, seeing as youll want him alive.”

“You’re not afraid, are you, Baltasar? What do you make of this ‘sea-devil’ anyway?”

“What can I make of a jaguar that takes to the air or a shark that climbs the trees? A beast you don’t know is terrifying. But I like my game terrifying.”

“I’ll make it worth your while.” Zurita placed an assuring hand on Baltasar’s arm.

“The fewer people in on it, the better,” he went on elaborating his plan. “You speak to the Araucanians we have on board. They’ve got more guts between them than the rest. Pick half a dozen from them, no more. If ours hold back, look about for others on shore. The ‘devil’ seems to be keeping close inshore. Well try and locate his lair first. Then we’ll know where to shoot our net.”

They wasted no time. Zurita had a wire bag net that looked like a big barrel with the bottom open made to order. Inside it he spread ordinary nets, in a way calculated to enmesh the devil. The divers were paid off. Baltasar had only managed to enlist two Araucanians from the crew. Another three he had signed on in Buenos Aires.

It was decided to start the “devil” hunt in the bay where they had first seen it. The schooner dropped anchor a few miles off the bay so as not to arouse the ‘devil’s’ suspicions. While Zurita’s party occupied themselves with occasional fishing-to justify their hanging around-they took turns in watching the waters of the bay from the shelter of some rocks on the shore.

A second week was running out but there was still no sign of the “devil.”

Baltasar had struck up acquaintance with some Indians from a farming village nearby. He would sell them the daily catch at half-price and then stay behind for a chat, cleverly bringing up the subject of the “sea-devil”. Soon the old Indian knew that they had been right in choosing the spot. Indeed, many villagers had heard the horn and seen the footprints on the beach. They said that the heels looked quite human but the toes were much too long. Sometimes they would find an imprint of the devil’s back on the beach where he had lain.

The “devil” was not known to have done anybody any harm, so the villagers had long ceased to mind the traces he left behind. Besides, none of them had actually seen him.

For two weeks the Jellyfish had kept near the bay, going on with the make-believe fishing. For two weeks Zurita, Baltasar and the hired Indians had scanned the bay, but still no “sea-devil” would show up. Zurita fretted and raged. He was as stingy as he was impatient. Every day cost money and that “devil” had kept them cooling their heels there many days now. Pedro was assailed by doubts. Suppose the creature was really a devil? Then no nets would catch him. Neither did superstitious Zurita particularly like the idea of meddling with one. Of course he could call a priest on board to bless the undertaking, but that would involve additional expense. And then, again, the creature might be some first-rate swimmer disguised as a “devit” to put fear into people for the sheer fun of it. There was the dolphin, of course. But that could have been tamed and trained like any other animal. Wouldn’t it be better to drop the whole thing, he wondered.

Zurita promised a reward to the first man to spot the “devil” and, tormented with doubts, decided to wait a few days longer.

To his immense joy the third week brought signs of the “devil’s” renewed activity.

One evening Baltasar tied up his boat, laden with that day’s catch to be sold in the morning, and went to a nearby farm to visit an Indian friend. On his return he found the boat empty. Baltasar was convinced that it was the “devil’s” handiwork though he couldn’t stop marvelling at the amount of fish the “devil” had put away.

Later that evening the Indian on duty reported having heard the sound of a horn coming from the south. Two days later, early in the morning, the youngest Araucanian finally spotted the “devil”. He came in from sea in the dolphin’s company, not riding it this time but swimming alongside, grasping with one hand a broad leather collar round the dolphin’s neck. In the bay the “devil” took the collar off the dolphin, patted it on the back, swam to the foot of a sheer cliff that jutted high on the shore and was seen no more.

On hearing the Indian’s report Zurita promised not to forget about the reward and said: “The ‘devil’ isn’t likely to stir from his den today. That gives us a chance to have a look at the sea-bed. Now, then, who’s willing?”

But that was a risk nobody was eager to take.

Then Baltasar stepped forward.

“I’m willing,” was all he said. Baltasar wasn’t one to go back on his word.

Leaving a watchman on board they went ashore and to the steep cliff.

Baltasar wound the end of diving cord round his middle, took a knife, seized a stone between his knees and went down.

The Araucanians waited in tense silence for his appearance, peering into the water, murky blue where the cliff cast a deep shadow. A slow minute went by. At last there was a tug at the cord. When Baltasar had been helped ashore it was some time before he could say, panting:

“There’s a narrow passage down there-leads into a cave-as dark as a shark’s belly. And no other place for the ‘devil’ to be gone to-just a sheer wall of rock all round.”

“Splendid! “ exclaimed Zurita. “The darker, the better. We only have to cast the net and wait for the blighter to walk in.”

Dusk was falling on the bay when the Indians lowered the wire net into the water across the mouth of the cave and secured the sturdy end ropes to rocks on shore. Then Baltasar tied a number of small bells to the ropes for early warning.

That done, Zurita, Baltasar and the five Araucanians settled down on the sand to await developments, Nobody had been left on board the schooner this time. All hands were needed.

The night darkened swiftly. Presently the moon appeared and silvered the surface of the ocean. The hush of night enveloped the beach. The little party sat on in tense silence. Any minute now they might see that strange creature that had been striking terror into the fishermen and pearl-divers.

The night dragged on. People began drowsing.

All of a sudden the bells rang. The men sprang up, ran for the end ropes and heaved. The net felt heavy. The ropes tautened. Something seemed to be struggling in the net.

At last the net came up and the pale moonlight revealed in it the body of a half-man, half-beast writhing and struggling to get free. The enormous eyes and silvery scales glistened, moonlit. The “devil” made desperate attempts to free his right hand, caught in the wire meshes. Finally he succeeded, unsheathed the knife that hung on a narrow leather belt at his side and started hacking at the net.

“No, you don’t, not a wire net,” Baltasar muttered under his breath.

But to his surprise the “devil’s” knife was whetted to the task. As the divers heaved at the net for all they were worth to get it on shore the “devil” was deftly widening the gash he had already made.

“Heave-ho, my hearties,” Baltasar shouted urgently.

But at the very moment when their quarry seemed as good as in their hands the “devil” dropped through the gash into the water, sending up a cascade of sparkling spray, and was gone.

The men stopped heaving in desperation.

“That’s some knife-cutting wire as you’d cut a loaf of fresh bread,” Baltasar said admiringly. “The underwater blacksmiths must be a darned sight better’n ours.”

Staring into the water Zurita had the air of a man who had lost all his fortune at one stroke.

Then he raised his head, tugged at his bristly moustache and stamped his foot.

“But no, damn you, this isn’t the end! “ he exclaimed. “I won’t give up if I have to starve you in your bleeding cave. I’ll spare no money, I’ll hire divers, I’ll have nets and traps put everywhere but I’ll get you! “

Whatever Zurita was lacking in, it was certainly not purpose and courage. This he had got with the hot blood of Spanish conquistadors that ran in his veins. And then he thought the thing was worth a fight, all the more so considering the “devil” was not half as formidable as he had feared.

A creature that could be made to tap the riches of the world for him would repay itself many times over. Zurita was going to have it, be it even guarded by Neptune himself.

Dr. Salvator

Nor did Zurita go back on his word. He had had the mouth of the cave and the waters nearby crossed and recrossed with barbed wire and sturdy nets with ingenious traps guarding the few free passages left. But there was only fish to reward him for his pains. The “sea-devil” had not shown up once. In fact he seemed to have disappeared altogether. His dolphin friend put in a daily appearance in the bay, snorting and gambol-ling in the waters, apparently eager for an outing. But all in vain. Presently the dolphin would give a final snort and head for the open sea.

Then the weather changed for the worse. The easterner lashed up a big swell; sand whipped from the sea-bed made the water so opaque that nothing could be seen beneath the foamy crests.

Zurita could spend hours on the shore, watching one huge white-headed breaker after another pound the beach. Broken, they hissed their way through the sand, rolling over pebbles and oyster shells, onto his very feet.

“This can’t go on,” Zurita said to himself one day. “Something must be done about it. The creature’s got his den at the bottom of the sea and he won’t stir from it. Very well. So he who wants to catch him must pay him a visit. Plain as the nose on your face.” And turning to Baltasar who was making another trap for the “devil” he said:

“Go straightway to Buenos Aires and get two diving outfits with oxygen sets. Ordinary ones won’t do. The ‘devil’s’ sure to cut the breathing tubes. Besides we might have to make quite a trip underwater. And mind you don’t forget electric torches as well.”

“Thinking of giving the ‘devil’ a look-up?” asked Baltasar.

“In your company, old cock. Yes.”

Baltasar nodded and set off on his errand.

When he returned he showed Zurita besides two diving suits and torches two long elaborately-curved bronze knives.

“They don’t make their kind nowadays,” he said. “These’re ancient knives my forefathers used to slit open the bellies of your forefathers with – if you don’t mind my saying so.”

Zurita didn’t care for the history part of it but he liked the knives.

Early at dawn the next day, despite a choppy sea, Zurita and Baltasar got into their diving suits and went down. It cost them considerable effort to find a way through their own nets to the mouth of the cave. Complete darkness met them. They unsheathed their knives and switched on their torches. Small fish darted away, scared by the sudden glare, then came back, swarming, mosquito-like, in the two bluish beams.

Zurita shooed them away: their silvery scales were fairly blinding him. The divers found themselves in a biggish cave, about twelve feet high and twenty feet wide. It was empty, except for the fish apparently sheltering there from the storm or bigger fish.

Treading cautiously they went deeper into the cave. It gradually narrowed. Suddenly Zurita stopped dead. The beam of his torch had picked out from the darkness a stout iron grille blocking their way.

Zurita could not believe his own eyes. He gripped at the iron bars in an attempt to pull the grille open. It didn’t give. After a closer look Zurita realized that it was securely embedded in the hewn-stone walls of the cave and had a built-in lock.

They were faced with still another riddle.

The “sea-devil” had apparently even greater intelligence than they had ever credited him with. He knew how to forge an iron grille to bar the way to his underwater den. But that was utterly impossible! He couldn’t have forged it actually under the water, could he! That meant he didn’t live underwater at all or at least that he went ashore for long stretches of time.

Zurita felt his blood throb in his temples as though he had used up his store of oxygen in those few minutes under water.

He motioned to Baltasar and they went out of the cave, and came up.

The Araucanians who had been on tenterhooks waiting for them were very glad to see them back.

“What do you make of it, Baltasar?” said Zurita after he had taken off his helmet and recovered his breath.

The Araucanian shrugged his shoulders.

“We’ll be ages waiting for him to come out, unless, of course, we dynamite the grille. We can’t starve him out, all he needs is fish and there’s plenty of that.”

“Do you think, Baltasar, there might be another way out of the cave – inland I mean?”

Baltasar hadn’t thought of that.

“It’s an idea though. Why didn’t we have a look round first,” said Zurita.

So he started on a new search.

On shore Zurita came across a high solid white-stone wall and followed it round. It completely encircled a piece of land, no less than twenty-five acres. There was only one gate, made of solid steel plates. In one corner of it there was a small steel door with a spy-hole shut from inside.

A regular fortress, thought Zurita. Very fishy. The farmers round here don’t normally build high walls. And not a chink anywhere to have a peep through.

There was not a sign of another habitation in the immediate neighbourhood, just bald grey rocks, with an occasional patch of thorny bush and cactus, all the way down to the bay.

Zurita’s curiosity was roused. For two days he haunted the rocks round the wall, keeping a specially sharp eye on the steel gate. But nobody went in or out, nor did a single sound come from within.

One evening, on board the Jellyfish, Zurita sought out Baltasar.

“Any idea who lives in the fortress above the bay?” he asked.

“Salvator-so the Indian farm-labourers tell me.”

“And who’s he?”

“God.”

The Spaniard’s bushy black eyebrows invaded his forehead.

“Having your joke, eh?”

A faint smile touched the Indian’s lips.

“I’m telling you what I’ve been told. Many Indians call Salvator a God and their saviour.”

“What does he save them from?”

“Death. He’s all-powerful, they say. He can work miracles. He holds life and death in the hollow of his hand, they say. He makes new, sound legs for the lame, keen eyes for the blind, he can even breathe life into the dead.”

“Carramba! “ muttered Zurita, as he flicked up smartly his bushy moustache. “There’s a ‘sea-devil’ down the bay, and a ‘god’ up it. I wonder if they’re partners.”

“If you take my advice we’ll clear out of here, and mighty quick, before our brains curdle with all these miracles.”

“Have you seen anyone who was treated by Salvator?”

“I have. I was shown a man who had been carried to Salvator with a broken leg. He was running about like a mustang. Then I saw an Indian whom Salvator had brought back to life. The whole village say that he was stone-dead with a split skull. Salvator put him on his feet again. He came back, full of life and laughter. Got married to a nice girl too. And then all those children-”

“So Salvator does receive patients?”

“Indians. They flock to him from everywhere-from as far away as Tierra del Fuego and the Amazon.”

Not satisfied with this information Zurita went up to Buenos Aires.

There too he learned that Salvator treated only Indians with whom he enjoyed the fame of a miracle-worker. Medical men told Zurita that Salvator was an exceptionally gifted surgeon, indeed a man of genius, but very eccentric, as is often the case with men of his calibre. His name was well known in medical circles on both sides of the Atlantic. In America he was famed for his bold imaginative surgery. When surgeons gave up a case as hopeless Salvator was asked to step in. He never refused. During the Great War he was on the French front where he operated almost exclusively on the brain. Thousands of men owed him their lives. After the Armistice he went back home. His practice and real estate operations landed in his lap quite a fortune. He threw up his practice, bought some land near Buenos Aires, had a high wall built round it (another of his eccentricities), and settled down there. He was known to have taken up research. Now he only treated Indians, who called him God descended on earth.

Finally Zurita found out that before the War right where his present vast holding lay Salvator had had a house with an orchard also walled in on all sides. When Salvator had been away in France the house had been closely guarded by a Black and a pack of ferocious bloodhounds.

Of late Salvator had lived a still more cloistered life. He wouldn’t receive even his old university colleagues.

Having gleaned all this information, Zurita decided to take illness so as to get inside the grounds.

Once again he was in front of the stout steel gate guarding Salvator’s property. He rapped on the gate. Nobody answered. He kept rapping on it for some time and still there was not a stir inside. His blood up, Zurita picked up a stone and started battering the gate, raising a din fit to wake the dead.

Dogs barked somewhere well inside and at last the spy-hole was slid open.

“What do you want?” a voice asked in broken Spanish.

“A sick man to see the doctor-hurry up now, open the door.”

“Sick men do not knock in this way,” came the placid rejoinder and an eye peeped through at Zurita. “Doctor’s not receiving.”

“He can’t refuse help to a sick man,” insisted Zurita.

The spy-hole shut; the footsteps died away. Only the dogs kept up their furious barking.

Venting some of his anger in choice invective, the Spaniard set out for the schooner.

Should he lodge a complaint against Salvator in Buenos Aires, he asked himself once he was aboard. But what was the use? Zurita shook in futile rage. His bushy black moustache was in real danger now as he kept tugging at it in his agitation, making it fall like a barometer showing the doldrums.

Little by little, however, he quietened down and set to thinking what he should do next.

As he went on thinking his sunburnt fingers would travel up more and more often to give a flip to his drooping moustache. The barometer was rising.

At last he emerged on deck, and to everybody’s surprise, ordered the crew to weigh anchor.

The Jellyfish stood for Buenos Aires.

“And about time too,” Baltasar commented. “So much time and effort wasted. A curse on that ‘devil’ with a ‘god’ for a crony!”

The Sick Granddaughter

The sun was angrily hot. An old Indian, thin and ragged, was plodding along a dusty country road that ran through alternating fields of wheat, maize and oats. In his arms he carried a child covered against the sun with a little blanket very much the worse for wear. The child’s eyes were half-closed; an enormous tumour bulged high on its neck. Whenever the old man stumbled the child groaned hoarsely and its eyelids quivered. Then the old man would stand still to blow into its face.

“If only I can get it there alive,” he whispered and quickened his pace.

Once in front of the steel gate the old Indian shifted the child onto his left arm and gave the side door four raps with his right hand.

He had a glimpse of an eye through the spy-hole, the bolts rattled and the door swung open.

The Indian stepped timidly inside. Standing in front of him was a white-smocked old Black with a head of snowwhite hair.

“I’ve brought a sick child,” the Indian said.

The Black nodded, shot the bolts home and motioned to the Indian to follow.

The Indian looked round him. He found himself in a small prison-like court, paved with big flagstones, with not a blade of grass anywhere. A wall lower than the outer one divided the court from the rest of the estate. At the gateway in the inner wall stood a large-windowed whitewashed building. Near it squatted a group of Indians-men, women and children.

Some of the children were playing jackstones with shells, others were wrestling in silence. The old Black saw to it that they did not disturb the peace of the place.

The old man eased himself down submissively in the shade of the building and started blowing into the child’s bluish inert face. An old Indian woman squatting down beside him threw a glance at the pair.

“Daughter?” she asked.