полная версия

полная версияThe Colonel's Dream

Charles W. Chesnutt

The Colonel's Dream

DEDICATION

To the great number of those who are seeking, in whatever manner or degree, from near at hand or far away, to bring the forces of enlightenment to bear upon the vexed problems which harass the South, this volume is inscribed, with the hope that it may contribute to the same good end.

If there be nothing new between its covers, neither is love new, nor faith, nor hope, nor disappointment, nor sorrow. Yet life is not the less worth living because of any of these, nor has any man truly lived until he has tasted of them all.

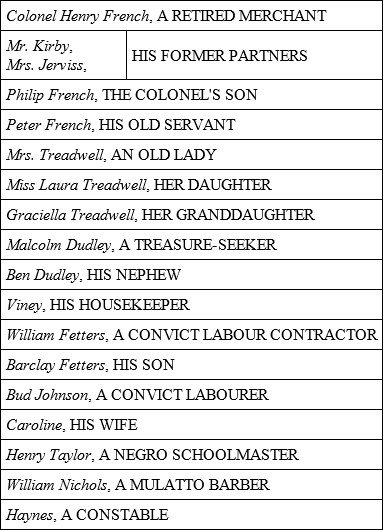

LIST OF CHARACTERS

One

Two gentlemen were seated, one March morning in 189—, in the private office of French and Company, Limited, on lower Broadway. Mr. Kirby, the junior partner—a man of thirty-five, with brown hair and mustache, clean-cut, handsome features, and an alert manner, was smoking cigarettes almost as fast as he could roll them, and at the same time watching the electric clock upon the wall and getting up now and then to stride restlessly back and forth across the room.

Mr. French, the senior partner, who sat opposite Kirby, was an older man—a safe guess would have placed him somewhere in the debatable ground between forty and fifty; of a good height, as could be seen even from the seated figure, the upper part of which was held erect with the unconscious ease which one associates with military training. His closely cropped brown hair had the slightest touch of gray. The spacious forehead, deep-set gray eyes, and firm chin, scarcely concealed by a light beard, marked the thoughtful man of affairs. His face indeed might have seemed austere, but for a sensitive mouth, which suggested a reserve of humour and a capacity for deep feeling. A man of well-balanced character, one would have said, not apt to undertake anything lightly, but sure to go far in whatever he took in hand; quickly responsive to a generous impulse, and capable of a righteous indignation; a good friend, a dangerous enemy; more likely to be misled by the heart than by the head; of the salt of the earth, which gives it savour.

Mr. French sat on one side, Mr. Kirby on the other, of a handsome, broad-topped mahogany desk, equipped with telephones and push buttons, and piled with papers, account books and letter files in orderly array. In marked contrast to his partner's nervousness, Mr. French scarcely moved a muscle, except now and then to take the cigar from his lips and knock the ashes from the end.

"Nine fifty!" ejaculated Mr. Kirby, comparing the clock with his watch. "Only ten minutes more."

Mr. French nodded mechanically. Outside, in the main office, the same air of tense expectancy prevailed. For two weeks the office force had been busily at work, preparing inventories and balance sheets. The firm of French and Company, Limited, manufacturers of crashes and burlaps and kindred stuffs, with extensive mills in Connecticut, and central offices in New York, having for a long time resisted the siren voice of the promoter, had finally faced the alternative of selling out, at a sacrifice, to the recently organised bagging trust, or of meeting a disastrous competition. Expecting to yield in the end, they had fought for position—with brilliant results. Negotiations for a sale, upon terms highly favourable to the firm, had been in progress for several weeks; and the two partners were awaiting, in their private office, the final word. Should the sale be completed, they were richer men than they could have hoped to be after ten years more of business stress and struggle; should it fail, they were heavy losers, for their fight had been expensive. They were in much the same position as the player who had staked the bulk of his fortune on the cast of a die. Not meaning to risk so much, they had been drawn into it; but the game was worth the candle.

"Nine fifty-five," said Kirby. "Five minutes more!"

He strode over to the window and looked out. It was snowing, and the March wind, blowing straight up Broadway from the bay, swept the white flakes northward in long, feathery swirls. Mr. French preserved his rigid attitude, though a close observer might have wondered whether it was quite natural, or merely the result of a supreme effort of will.

Work had been practically suspended in the outer office. The clerks were also watching the clock. Every one of them knew that the board of directors of the bagging trust was in session, and that at ten o'clock it was to report the result of its action on the proposition of French and Company, Limited. The clerks were not especially cheerful; the impending change meant for them, at best, a change of masters, and for many of them, the loss of employment. The firm, for relinquishing its business and good will, would receive liberal compensation; the clerks, for their skill, experience, and prospects of advancement, would receive their discharge. What else could be expected? The principal reason for the trust's existence was economy of administration; this was stated, most convincingly, in the prospectus. There was no suggestion, in that model document, that competition would be crushed, or that, monopoly once established, labour must sweat and the public groan in order that a few captains, or chevaliers, of industry, might double their dividends. Mr. French may have known it, or guessed it, but he was between the devil and the deep sea—a victim rather than an accessory—he must take what he could get, or lose what he had.

"Nine fifty-nine!"

Kirby, as he breathed rather than spoke the words, threw away his scarcely lighted cigarette, and gripped the arms of his chair spasmodically. His partner's attitude had not varied by a hair's breadth; except for the scarcely perceptible rise and fall of his chest he might have been a wax figure. The pallor of his countenance would have strengthened the illusion.

Kirby pushed his chair back and sprung to his feet. The clock marked the hour, but nothing happened. Kirby was wont to say, thereafter, that the ten minutes that followed were the longest day of his life. But everything must have an end, and their suspense was terminated by a telephone call. Mr. French took down the receiver and placed it to his ear.

"It's all right," he announced, looking toward his partner. "Our figures accepted—resolution adopted—settlement to-morrow. We are–"

The receiver fell upon the table with a crash. Mr. French toppled over, and before Kirby had scarcely realised that something was the matter, had sunk unconscious to the floor, which, fortunately, was thickly carpeted.

It was but the work of a moment for Kirby to loosen his partner's collar, reach into the recesses of a certain drawer in the big desk, draw out a flask of brandy, and pour a small quantity of the burning liquid down the unconscious man's throat. A push on one of the electric buttons summoned a clerk, with whose aid Mr. French was lifted to a leather-covered couch that stood against the wall. Almost at once the effect of the stimulant was apparent, and he opened his eyes.

"I suspect," he said, with a feeble attempt at a smile, "that I must have fainted—like a woman—perfectly ridiculous."

"Perfectly natural," replied his partner. "You have scarcely slept for two weeks—between the business and Phil—and you've reached the end of your string. But it's all over now, except the shouting, and you can sleep a week if you like. You'd better go right up home. I'll send for a cab, and call Dr. Moffatt, and ask him to be at the hotel by the time you reach it. I'll take care of things here to-day, and after a good sleep you'll find yourself all right again."

"Very well, Kirby," replied Mr. French, "I feel as weak as water, but I'm all here. It might have been much worse. You'll call up Mrs. Jerviss, of course, and let her know about the sale?"

When Mr. French, escorted to the cab by his partner, and accompanied by a clerk, had left for home, Kirby rang up the doctor, and requested him to look after Mr. French immediately. He then called for another number, and after the usual delay, first because the exchange girl was busy, and then because the line was busy, found himself in communication with the lady for whom he had asked.

"It's all right, Mrs. Jerviss," he announced without preliminaries. "Our terms accepted, and payment to be made, in cash and bonds, as soon as the papers are executed, when you will be twice as rich as you are to-day."

"Thank you, Mr. Kirby! And I suppose I shall never have another happy moment until I know what to do with it. Money is a great trial. I often envy the poor."

Kirby smiled grimly. She little knew how near she had been to ruin. The active partners had mercifully shielded her, as far as possible, from the knowledge of their common danger. If the worst happened, she must know, of course; if not, then, being a woman whom they both liked—she would be spared needless anxiety. How closely they had skirted the edge of disaster she did not learn until afterward; indeed, Kirby himself had scarcely appreciated the true situation, and even the senior partner, since he had not been present at the meeting of the trust managers, could not know what had been in their minds.

But Kirby's voice gave no hint of these reflections. He laughed a cheerful laugh. "If the world only knew," he rejoined, "it would cease to worry about the pains of poverty, and weep for the woes of wealth."

"Indeed it would!" she replied, with a seriousness which seemed almost sincere. "Is Mr. French there? I wish to thank him, too."

"No, he has just gone home."

"At this hour?" she exclaimed, "and at such a time? What can be the matter? Is Phil worse?"

"No, I think not. Mr. French himself had a bad turn, for a few minutes, after we learned the news."

Faces are not yet visible over the telephone, and Kirby could not see that for a moment the lady's grew white. But when she spoke again the note of concern in her voice was very evident.

"It was nothing—serious?"

"Oh, no, not at all, merely overwork, and lack of sleep, and the suspense—and the reaction. He recovered almost immediately, and one of the clerks went home with him."

"Has Dr. Moffatt been notified?" she asked.

"Yes, I called him up at once; he'll be at the Mercedes by the time the patient arrives."

There was a little further conversation on matters of business, and Kirby would willingly have prolonged it, but his news about Mr. French had plainly disturbed the lady's equanimity, and Kirby rang off, after arranging to call to see her in person after business hours.

Mr. Kirby hung up the receiver with something of a sigh.

"A fine woman," he murmured, "I could envy French his chances, though he doesn't seem to see them—that is, if I were capable of envy toward so fine a fellow and so good a friend. It's curious how clearsighted a man can be in some directions, and how blind in others."

Mr. French lived at the Mercedes, an uptown apartment hotel overlooking Central Park. He had scarcely reached his apartment, when the doctor arrived—a tall, fair, fat practitioner, and one of the best in New York; a gentleman as well, and a friend, of Mr. French.

"My dear fellow," he said, after a brief examination, "you've been burning the candle at both ends, which, at your age won't do at all. No, indeed! No, indeed! You've always worked too hard, and you've been worrying too much about the boy, who'll do very well now, with care. You've got to take a rest—it's all you need. You confess to no bad habits, and show the signs of none; and you have a fine constitution. I'm going to order you and Phil away for three months, to some mild climate, where you'll be free from business cares and where the boy can grow strong without having to fight a raw Eastern spring. You might try the Riviera, but I'm afraid the sea would be too much for Phil just yet; or southern California—but the trip is tiresome. The South is nearer at hand. There's Palm Beach, or Jekyll Island, or Thomasville, Asheville, or Aiken—somewhere down in the pine country. It will be just the thing for the boy's lungs, and just the place for you to rest. Start within a week, if you can get away. In fact, you've got to get away."

Mr. French was too weak to resist—both body and mind seemed strangely relaxed—and there was really no reason why he should not go. His work was done. Kirby could attend to the formal transfer of the business. He would take a long journey to some pleasant, quiet spot, where he and Phil could sleep, and dream and ride and drive and grow strong, and enjoy themselves. For the moment he felt as though he would never care to do any more work, nor would he need to, for he was rich enough. He would live for the boy. Phil's education, his health, his happiness, his establishment in life—these would furnish occupation enough for his well-earned retirement.

It was a golden moment. He had won a notable victory against greed and craft and highly trained intelligence. And yet, a year later, he was to recall this recent past with envy and regret; for in the meantime he was to fight another battle against the same forces, and others quite as deeply rooted in human nature. But he was to fight upon a new field, and with different weapons, and with results which could not be foreseen.

But no premonition of impending struggle disturbed Mr. French's pleasant reverie; it was broken in a much more agreeable manner by the arrival of a visitor, who was admitted by Judson, Mr. French's man. The visitor was a handsome, clear-eyed, fair-haired woman, of thirty or thereabouts, accompanied by another and a plainer woman, evidently a maid or companion. The lady was dressed with the most expensive simplicity, and her graceful movements were attended by the rustle of unseen silks. In passing her upon the street, any man under ninety would have looked at her three times, the first glance instinctively recognising an attractive woman, the second ranking her as a lady; while the third, had there been time and opportunity, would have been the long, lingering look of respectful or regretful admiration.

"How is Mr. French, Judson?" she inquired, without dissembling her anxiety.

"He's much better, Mrs. Jerviss, thank you, ma'am."

"I'm very glad to hear it; and how is Phil?"

"Quite bright, ma'am, you'd hardly know that he'd been sick. He's gaining strength rapidly; he sleeps a great deal; he's asleep now, ma'am. But, won't you step into the library? There's a fire in the grate, and I'll let Mr. French know you are here."

But Mr. French, who had overheard part of the colloquy, came forward from an adjoining room, in smoking jacket and slippers.

"How do you do?" he asked, extending his hand. "It was mighty good of you to come to see me."

"And I'm awfully glad to find you better," she returned, giving him her slender, gloved hand with impulsive warmth. "I might have telephoned, but I wanted to see for myself. I felt a part of the blame to be mine, for it is partly for me, you know, that you have been overworking."

"It was all in the game," he said, "and we have won. But sit down and stay awhile. I know you'll pardon my smoking jacket. We are partners, you know, and I claim an invalid's privilege as well."

The lady's fine eyes beamed, and her fair cheek flushed with pleasure. Had he only realised it, he might have claimed of her any privilege a woman can properly allow, even that of conducting her to the altar. But to him she was only, thus far, as she had been for a long time, a very good friend of his own and of Phil's; a former partner's widow, who had retained her husband's interest in the business; a wholesome, handsome woman, who was always excellent company and at whose table he had often eaten, both before and since her husband's death. Nor, despite Kirby's notions, was he entirely ignorant of the lady's partiality for himself.

"Doctor Moffatt has ordered Phil and me away, for three months," he said, after Mrs. Jerviss had inquired particularly concerning his health and Phil's.

"Three months!" she exclaimed with an accent of dismay. "But you'll be back," she added, recovering herself quickly, "before the vacation season opens?"

"Oh, certainly; we shall not leave the country."

"Where are you going?"

"The doctor has prescribed the pine woods. I shall visit my old home, where I was born. We shall leave in a day or two."

"You must dine with me to-morrow," she said warmly, "and tell me about your old home. I haven't had an opportunity to thank you for making me rich, and I want your advice about what to do with the money; and I'm tiring you now when you ought to be resting."

"Do not hurry," he said. "It is almost a pleasure to be weak and helpless, since it gives me the privilege of a visit from you."

She lingered a few moments and then went. She was the embodiment of good taste and knew when to come and when to go.

Mr. French was conscious that her visit, instead of tiring him, had had an opposite effect; she had come and gone like a pleasant breeze, bearing sweet odours and the echo of distant music. Her shapely hand, when it had touched his own, had been soft but firm; and he had almost wished, as he held it for a moment, that he might feel it resting on his still somewhat fevered brow. When he came back from the South, he would see a good deal of her, either at the seaside, or wherever she might spend the summer.

When Mr. French and Phil were ready, a day or two later, to start upon their journey, Kirby was at the Mercedes to see them off.

"You're taking Judson with you to look after the boy?" he asked.

"No," replied Mr. French, "Judson is in love, and does not wish to leave New York. He will take a vacation until we return. Phil and I can get along very well alone."

Kirby went with them across the ferry to the Jersey side, and through the station gates to the waiting train. There was a flurry of snow in the air, and overcoats were comfortable. When Mr. French had turned over his hand luggage to the porter of the Pullman, they walked up and down the station platform.

"I'm looking for something to interest us," said Kirby, rolling a cigarette. "There's a mining proposition in Utah, and a trolley railroad in Oklahoma. When things are settled up here, I'll take a run out, and look the ground over, and write to you."

"My dear fellow," said his friend, "don't hurry. Why should I make any more money? I have all I shall ever need, and as much as will be good for Phil. If you find a good thing, I can help you finance it; and Mrs. Jerviss will welcome a good investment. But I shall take a long rest, and then travel for a year or two, and after that settle down and take life comfortably."

"That's the way you feel now," replied Kirby, lighting another cigarette, "but wait until you are rested, and you'll yearn for the fray; the first million only whets the appetite for more."

"All aboard!"

The word was passed along the line of cars. Kirby took leave of Phil, into whose hand he had thrust a five-dollar bill, "To buy popcorn on the train," he said, kissed the boy, and wrung his ex-partner's hand warmly.

"Good-bye," he said, "and good luck. You'll hear from me soon. We're partners still, you and I and Mrs. Jerviss."

And though Mr. French smiled acquiescence, and returned Kirby's hand clasp with equal vigour and sincerity, he felt, as the train rolled away, as one might feel who, after a long sojourn in an alien land, at last takes ship for home. The mere act of leaving New York, after the severance of all compelling ties, seemed to set in motion old currents of feeling, which, moving slowly at the start, gathered momentum as the miles rolled by, until his heart leaped forward to the old Southern town which was his destination, and he soon felt himself chafing impatiently at any delay that threatened to throw the train behind schedule time.

"He'll be back in six weeks," declared Kirby, when Mrs. Jerviss and he next met. "I know him well; he can't live without his club and his counting room. It is hard to teach an old dog new tricks."

"And I'm sure he'll not stay away longer than three months," said the lady confidently, "for I have invited him to my house party."

"A privilege," said Kirby gallantly, "for which many a man would come from the other end of the world."

But they were both mistaken. For even as they spoke, he whose future each was planning, was entering upon a new life of his own, from which he was to look back upon his business career as a mere period of preparation for the real end and purpose of his earthly existence.

Two

The hack which the colonel had taken at the station after a two-days' journey, broken by several long waits for connecting trains, jogged in somewhat leisurely fashion down the main street toward the hotel. The colonel, with his little boy, had left the main line of railroad leading north and south and had taken at a certain way station the one daily train for Clarendon, with which the express made connection. They had completed the forty-mile journey in two or three hours, arriving at Clarendon at noon.

It was an auspicious moment for visiting the town. It is true that the grass grew in the street here and there, but the sidewalks were separated from the roadway by rows of oaks and elms and china-trees in early leaf. The travellers had left New York in the midst of a snowstorm, but here the scent of lilac and of jonquil, the song of birds, the breath of spring, were all about them. The occasional stretches of brick sidewalk under their green canopy looked cool and inviting; for while the chill of winter had fled and the sultry heat of summer was not yet at hand, the railroad coach had been close and dusty, and the noonday sun gave some slight foretaste of his coming reign.

The colonel looked about him eagerly. It was all so like, and yet so different—shrunken somewhat, and faded, but yet, like a woman one loves, carried into old age something of the charm of youth. The old town, whose ripeness was almost decay, whose quietness was scarcely distinguishable from lethargy, had been the home of his youth, and he saw it, strange to say, less with the eyes of the lad of sixteen who had gone to the war, than with those of the little boy to whom it had been, in his tenderest years, the great wide world, the only world he knew in the years when, with his black boy Peter, whom his father had given to him as a personal attendant, he had gone forth to field and garden, stream and forest, in search of childish adventure. Yonder was the old academy, where he had attended school. The yellow brick of its walls had scaled away in places, leaving the surface mottled with pale splotches; the shingled roof was badly dilapidated, and overgrown here and there with dark green moss. The cedar trees in the yard were in need of pruning, and seemed, from their rusty trunks and scant leafage, to have shared in the general decay. As they drove down the street, cows were grazing in the vacant lot between the bank, which had been built by the colonel's grandfather, and the old red brick building, formerly a store, but now occupied, as could be seen by the row of boxes visible through the open door, by the post-office.

The little boy, an unusually handsome lad of five or six, with blue eyes and fair hair, dressed in knickerbockers and a sailor cap, was also keenly interested in the surroundings. It was Saturday, and the little two-wheeled carts, drawn by a steer or a mule; the pigs sleeping in the shadow of the old wooden market-house; the lean and sallow pinelanders and listless negroes dozing on the curbstone, were all objects of novel interest to the boy, as was manifest by the light in his eager eyes and an occasional exclamation, which in a clear childish treble, came from his perfectly chiselled lips. Only a glance was needed to see that the child, though still somewhat pale and delicate from his recent illness, had inherited the characteristics attributed to good blood. Features, expression, bearing, were marked by the signs of race; but a closer scrutiny was required to discover, in the blue-eyed, golden-haired lad, any close resemblance to the shrewd, dark man of affairs who sat beside him, and to whom this little boy was, for the time being, the sole object in life.