полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 272, September 8, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 272, September 8, 1827

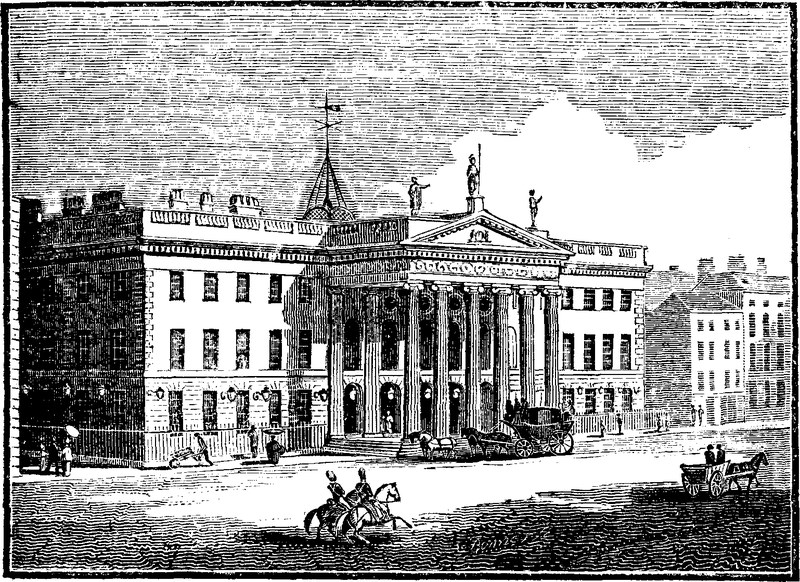

DUBLIN POST OFFICE.

DUBLIN POST OFFICE

The general post-office, Dublin, was at first held in a small building on the site of the Commercial Buildings, and was afterwards removed to a larger house opposite the bank on College Green (since converted into the Royal Arcade;) and on January 6, 1818, the new post-office in Sackville-street was opened for business.

The foundation-stone of this magnificent building, which is built after a design of Francis Johnson, Esq., was laid by his excellency Charles, Earl of Whitworth, August 12, 1814, and the structure was completed in the short space of three years, for the sum of 50,000l.

The front, which extends 220 feet, has a magnificent portico (80 feet wide), of six fluted Ionic columns, 4 feet 6 inches in diameter. The frieze of the entablature is highly enriched, and in the tympanum of the pediment are the royal arms. On the acroteria of the pediment are three statues by John Smyth, viz.—Mercury on the right, with his Caduceus and purse; On the left Fidelity, with her finger on her lip, and a key in her hand; and in the centre Hibernia, resting on her spear, and holding her shield. The entablature, with the exception of the architrave, is continued along the rest of the front; the frieze, however, is not decorated over the portico. A handsome balustrade surmounts the cornice of the building, which is 50 feet from the ground. With the exception of the portico, which is of Portland stone, the whole is of mountain granite. The elevation has three stories, of which the lower or basement is rusticated, and in this respect it resembles the India House of London, where a rusticated basement is introduced, although the portico occupies the entire height of the structure.

Over the centre of the building is seen a cupola, containing the chimes and bell on which the clock-hammer strikes. The bell is so loud, that it is heard in every part of the city.

The interior is particularly remarkable for the convenience of its arrangement, and the number of its communicating apartments. The board-room is a very handsome apartment, furnished with two seats, which are for the postmasters-general. Over the chimney-piece, protected by a curtain of green silk, is a bust of Earl Whitworth, in white marble, by John Smyth.

THE TOPOGRAPHER

HIGH CROSS

A Roman Station—the Camp of Claudius—Manners, Customs, and Dialects of the people of the District.

About two miles to the west of Little Claybrook, in the hundred of Luthlaxton, in Leicestershire, is a place called High Cross, which, according to some antiquarians, was the Benonce or Vennones of the Romans. Dr. Stukely describes this station as situated at the intersection of the two great Roman roads, "which traverse the kingdom obliquely, and seem to be the centre, as well as the highest ground in England; for from hence rivers run every way. The foss road went on the backside of an inn standing here, and so towards Bath. The ground hereabout is very rich, and much ebulus (a herb much sought after for the cure of dropsies,) grows here. Claybrooklane has a piece of quickset hedge left across it, betokening one side of the Foss; which road in this place bears exactly north-east and south-west as it does upon the moor on this side of Lincoln. In the garden before the inn abovementioned, a tumulus was removed about the year 1720, under which the body of a man was found upon the plain surface; as likewise hath been under several others hereabout; and foundations of buildings have been frequently dug up along the street here, all the way to Cleycestre, through which went the great street-way, called Watling-street; for on both sides of the way have been ploughed and dug up many ancient coins, great square stones and bricks, and other rubbish, of that ancient Roman building, not far from a beacon, standing upon the way now called High Cross, of a cross which stood there some time, upon the meeting of another great way."

At the intersection of the roads is the pedestal, &c. of a cross which was erected here in the year 1712; on which are the two following Latin inscriptions. On one side is—

Vicinarum provinciarum, Vervicensis scilicet et Leicestrensis, ornamenta, proceres patritiique, auspiciis, illustrissimi Basili Comitis de Denbeigh, hanc columnam statuendam curaverunt, in gratam pariter et perpetuam memoriam Jani tandem a Serenissima Anna clausi A.D. MDCCXII.

Which is thus translated,

The noblemen and gentry, ornaments of the neighbouring counties of Warwick and Leicester, at the instances of the Right Honourable Basil Earl of Denbeigh, have caused this pillar to be erected in grateful as well as perpetual remembrance of Peace at last restored by her Majesty Queen Anne, in the year of our Lord, 1712.

The inscription on the other side runs thus—

Si Veterum Romanorum vestigia quaeras, hic cernas viator. Hic enim celeberrimae illorum viae militares sese mutuo secantes ad extremes usque Britanniae limites procurent: hic stativa sua habuerunt Vennones; et ad primum ad hinc lapidem castra sua ad Stratam, et ad Fossam tumulum, Claudius quidam cohortis praefectus habuisse videtur.

Which may be thus rendered,

If, traveller, you search for the footsteps of the ancient Romans, here you may behold them. For here their most celebrated ways, crossing one another, extend to the utmost boundaries of Britain; here the Vennones kept their quarters; and at the distance of one mile from hence, Claudius, a certain commander of a cohort, seems to have had a camp, towards the street, and towards the foss a tomb.

The ground here is so high, and the surrounding country so low and flat, that it is said, fifty-seven churches may be seen from this spot by the help of a glass.

The following judicious remarks on the customs, mariners, and dialects of the common people of this district by Mr. Macauley, who published a history of Claybrook, may be amusing to many readers.—The people here are much attached to wakes; and among the farmers and cottagers these annual festivals are celebrated with music, dancing, feasting, and much inoffensive sport; but in the neighbouring villages the return of the wake never fails to produce at least a week of idleness, intoxication, and riot. These and other abuses by which those festivals are grossly perverted, render it highly desirable to all the friends of order and decency that they were totally suppressed. On Plow Monday is annually displayed a set of morice dancers; and the custom of ringing the curfew is still continued here, as well as the pancake bell on Shrove Tuesday. The dialect of the common people is broad, and partakes of the Anglo-Saxon sounds and terms. The letter h comes in almost on every occasion where it ought not, and it is frequently omitted where it ought to come in. The words fire, mire, and such like, are pronounced as if spelt foire, moire; and place, face, and other similar words, as if spelt pleace, feace; and in the plural you sometimes hear pleacen, closen, for closes, and many other words in the same style of Saxon termination. The words there, and where, are generally pronounced theere and wheere; the words mercy, deserve, thus, marcy, desarve. The following peculiarities are also observable: uz, strongly aspirated for us; war for was; meed for maid; faither for father; e'ery for every; brig for bridge; thurrough for furrow; hawf for half; cart rit for cart rut; malefactory for manufactory; inactions for anxious. The words mysen and himsen, are sometimes used for myself and himself; the word shoek is used to denote an idle worthless vagabond; and the word ripe for one who is very profane. The following phrases are common, "a power of people," "a hantle of money," "I can't awhile as yet." The words like and such frequently occur as expletives in conversation, "I won't stay here haggling all day and such." "If you don't give me my price like." The monosyllable as is generally substituted for that; "the last time as I called," "I reckon as I an't one," "I imagine as I am not singular." Public characters are stigmatized by saying, "that they set poor lights." The substantive right often supplies the place of ought, as "farmer A has a right to pay his tax." Next ways, and clever through, are in common use, as "I shall go clever through Ullesthorpe." "Nigh hand" for probably, as he will nigh hand call on us. Duable, convenient or proper: thus "the church is not served at duable hours." Wives of farmers often call their husbands "our master," and the husbands call their wives mamy, whilst a labourer will often distinguish his wife by calling her the "o'man." People now living remember when Goody and Dame, Gaffer and Gammer, were in vogue among the peasantry of Leicestershire; but they are now almost universally discarded and supplanted by Mr. and Mrs. which are indiscriminately applied to all ranks, from the squire and his lady down to Mr. and Mrs. Pauper, who flaunt in rags and drink tea twice a day."

SONG

TUNE,—"Love was once a Little Boy."(For the Mirror.)Beauty once was but a girl—Heigho! heigho!Coral lips and teeth of pearl;Heigho! heigho!Then 'twas hers, her arms to twineRound my neck, as at Love's shrine,Soft I zoned her waist with mine,Heigho! heigho!Beauty's grown a woman now,Heigho! heigho!Haughty mein and haughty brow,Heigho! heigho!Tossing high her head in air,As if she deems her charms so rare,Will ever be what once they were,Heigho! heigho!Beauty's charms will quickly fade,Heigho! heigho!Beauty's self, erelong, be dead,Heigho! heigho!And should Beauty haply die,Shall we only sit and sigh?No, Bacchus, no—thy charms we'll try!Heigho! heigho!H.BORIGINS AND INVENTIONS

No. XXIXGOING SNACKSDuring the period of the great plague the office of searcher, which is continued to the present day, was a very important one; and a noted body-searcher, whose name was Snacks, finding his business increase so fast that he could not compass it, offered to any person who should join him in his hazardous practice, half the profits; thus those who joined him were said to go with Snacks. Hence "going snacks," or dividing the spoil.1

ANTIPHONANT CHANTINGSt. Ambrose is considered as the first who introduced the antiphonant method of chanting, or one side of the choir alternately responding to the other; from whence that particular mode obtained the name of the "Ambrosian chant," while the plain song, introduced by St. Gregory, still practised in the Romish service, is called the "Gregorian," or "Romish chant." The works of St. Ambrose continue to be held in much respect, particularly the hymn of Te Deum, which he is said to have composed when he baptised St. Augustine, his celebrated convert.

THE NOVELIST

"I HAVE DONE MY DUTY."

A Tale of the Sea. 2 She would sit and weepAt what a sailor suffers; fancy, too,Delusive most where warmest wishes are,Would oft anticipate his glad return.COWPER."I dearly love a sailor!" exclaimed the beautiful and fascinating Mrs. D–, as she stood in the balcony of her house, leaning upon the arm of her affectionate and indulgent husband, and gazing at a poor shattered tar who supplicated charity by a look that could hardly fail of interesting the generous sympathies of the heart—"I dearly love a sailor; he is so truly the child of nature; and I never feel more disposed to shed tears, than when I see the hardy veteran who has sacrificed his youth, and even his limbs, in the service of his country—

"Cast abandoned on the world's wide stage,And doomed in scanty poverty to roam."Look at yon poor remnant of the tempest, probably reduced to the hard necessity of becoming a wanderer, without a home to shelter him, or one kind commiserating smile to shed a ray of sunshine on the dreary winter of his life. I can remember, when a child, I had an uncle who loved me very tenderly, and my attachment to him was almost that of a daughter; indeed he was the pride and admiration of our village; for every one esteemed him for his kind and cheerful disposition. But untoward events cast a gloom upon his mind; he hastened away to sea, and we never saw him more."

By this time the weather-beaten, care-worn seaman had advanced toward the house, and cast a wistful glance aloft; it was full of honest pride that disdained to beg, yet his appearance was so marked with every emblem of poverty and hunger, that, as the conflicting feelings worked within his breast, his countenance betrayed involuntarily the struggles of his heart. There was a manly firmness in his deportment, that bespoke no ordinary mind; and a placid serenity in his eye, that beamed with benevolence, and seemed only to regret that he could no longer be a friend to the poor and destitute, or share his hard-earned pittance with a messmate in distress. A few scattered grey locks peeped from beneath an old straw hat; and one sleeve of his jacket hung unoccupied by his side—the arm was gone. "I should like to know his history," said the amiable lady; "let us send for him in." To express a wish, and have it gratified, were the same thing to Mrs. D–, and in a few minutes the veteran tar stood before them. "Would you wish to hear a tale of woe?" cried the old man, in answer to her request. "Ah, no! why should your tender heart be wounded by another's griefs? I have been buffeted by the storms of affliction—I have struggled against the billows of adversity—every wave of sorrow has rolled over me; but," added he, while a glow of conscious integrity suffused his furrowed cheek, "I have always done my duty; and that conviction has buoyed me up when nearly overwhelmed in the ocean of distress. Yet, lady, it was not always thus: I have been happy—was esteemed, and, as I thought, beloved. I had a friend, in whom I reposed the highest confidence, and my affections were devoted to one;—but, she is gone—she is gone! and I—Yes! we shall meet again:"—here he paused, dashed a tear from his eye, and then proceeded:—"My friend was faithless; he robbed me of the dearest treasure of my heart, and blasted every hope of future happiness. I left my native land to serve my country; have fought her battles, and bled in her defence. On the 29th of May, and glorious 1st of June, 1794, I served on board the Queen Charlotte, under gallant Howe, and was severely wounded in the breast—but I did my duty. On that memorable occasion, a circumstance occured which added to my bitterness and melancholy. The decks were cleared—the guns cast loose, and every man stood in eager expectation at his quarters. It is an awful moment, lady, and various conflicting emotions agitate the breast when, in the calm stillness that reigns fore and aft, the mind looks back upon the past, and contemplates the future. Home, wife, children, and every tender remembrance rush upon the soul. It is different in the heat of action: then every faculty is employed for conquest, that each man may have to say, 'I have done my duty.' But when bearing down to engage, and silence is so profound that every whisper may be heard, then their state of mind—it cannot be described. Sailors know what it is, and conquering it by cool determination and undaunted bravery, nobly do their duty. I was stationed at the starboard side of the quarter deck, and looked around me with feelings incident to human nature, yet wishing for and courting death. The admiral, with calm composure, surrounded by his captains and signal officers, stood upon the beak of the poop, while brave Bowen, the master, occupied the ladder, and gave directions to the quarter-master at the helm. They opened their fire, and the captains of the guns stood ready with their matches in their hand, waiting for the word. The work of destruction commenced, and many of our shipmates lay bleeding on the deck, but not a shot had we returned. "Stand by there, upon the main deck," cried the first lieutenant. "Steady, my men! Wait for command, and don't throw your fire away!" "All ready, sir," was responded fore and aft.

At this moment a seaman advanced upon the quarter-deck, attended by a young lad (one of the fore-top men) whose pale face and quivering lip betrayed the tremulous agitation of fear. The lieutenant gazed at him for a few seconds with marked contempt and indignation, but all stood silent. The officer turned towards the admiral, and on again looking round, perceived that the lad had fainted, and lay lifeless in the seaman's arms, who gazed upon the bloodless countenance of his charge with a look of anguish and despair. "Carry him below," said the lieutenant, "and let him skulk from his duty; this day must be a day of glory!" The poor fellow seemed unconscious that he was spoken to, but still continued to gaze upon the lad. The officer beckoned to a couple of men, who immediately advanced, and were about to execute his orders, when the seaman put them back with his hand, exclaiming, 'No! she is mine, and we will live or die together!' Oh! lady, what a scene was that! The frown quitted the lieutenant's brow, and a tear trembled in his eye. The generous Howe and his brave companions gathered round, and there was not a heart that did not feel what it was to be beloved. Yes! mine alone was dreary, like the lightning-blasted wreck. We were rapidly approaching the French admiral's ship, the Montague: the main decks fired, and the lower deck followed the example. The noise brought her to her recollection; she gazed wildly on all, and then clinging closer to her lover, sought relief in tears. 'T–,' said his lordship, mildly, 'this must not be—Go, go, my lad; see her safe in the cockpit, and then I know that you will do your duty.' A smile of animation lighted up his agitated face. 'I will! I will!' cried he, God bless your lordship, I will! for I have always done my duty;'—and taking his trembling burthen in his arms, supported her to a place of safety. In a few minutes he was again at his gun, and assisted in pouring the first raking broadside into our opponents stern. Since that time I have served in most of the general actions; and knelt by the side of the hero Nelson, when he resigned himself to the arms of death. But, whether stationed upon deck amidst the blood and slaughter of battle—the shrieks of the wounded, and groans of the dying—or clinging to the shrouds during the tempestuous howling of the storm, while the wild waves were beating over me—whether coasting along the luxuriant shores of the Mediterranean, or surrounded by ice-bergs in the Polar sea,—one thought, one feeling possessed my soul, and that was devoted to the being I adored. Years rolled away; but that deep, strong, deathless passion distance could not subdue, nor old age founder. 'Tis now about seven years since the British troops under Wellington were landed on the Continent. I was employed with a party of seamen on shore in transporting the artillery and erecting batteries. A body of the French attacked one of our detachments, and, after considerable slaughter on both sides, the enemy were compelled to retreat. We were ordered to the field to bring in the wounded and prisoners. Never—never shall I forget that day: the remembrance even now unmans me. Oh, lady! forgive these tears, and pity the anguish of an old man's heart. Day had just began to dawn when we arrived upon the plain, and commenced our search among the bodies, to see if there were any who yet remained lingering in existence. Passing by and over heaps of dead, my progress was suddenly arrested, and every fibre of my heart was racked, on seeing a female sitting by the mangled remains of an English soldier. She was crouched upon the ground, her face resting on her lap, and every feature hid from view. Her long black hair hung in dishevelled flakes about her shoulders, and her garments closed round her person, heavy with the cold night-rains; one hand clasped that of the dead soldier, the other arm was thrown around his head. Every feeling of my soul was roused to exertion—I approached—she raised herself up, and—and—great Heaven! 'twas she—the woman whom I loved! She gazed with sickly horror; and, though greatly altered—though time and sorrow had chased away the bloom of health—though scarce a trace of former beauty remained, those features were too deeply engraven on my memory for me to be mistaken; but she knew me not. I forgot all my wrongs, and rushing forward, clasped her to my breast. Oh, what a moment was that! she made an ineffectual struggle for release, and then fainted in my arms. Some of my shipmates came to the spot, and, turning over the lifeless form before us, my eyes rested on the countenance of him who had once been nay friend. But death disarms resentment; he was beyond my vengeance, and had already been summoned to the tribunal of the Most High. When I had last seen them, affluence, prosperity, and happiness, were the portion of us all. Now—but I cannot, cannot repeat the distressing tale; let it suffice, lady, that she was carried to a place of safety, and every effort used to restore animation, in which we were eventually successful. How shall I describe our meeting, when she recognised me?—it is impossible; I feel it now in every nerve, but to tell you is beyond my power. Through the kindness of a generous officer, I procured her a passage to England, and gave her all that I possessed, with this one request, that she would remain at Plymouth till my return to port. In a few months afterwards we anchored in the Sound, and, as soon as duty would permit, I hastened to obtain leave to go on shore; it was denied me—yes, cruelly denied me. Stung to madness, I did not hesitate; but as soon as night had closed in, slipped down the cables and swam to land. With eager expectation I hurried to the house in which I had requested her to remain. I crossed the threshold unobserved, for all was silent as the grave, and gently ascended the stairs. The room door was partly open, and a faint light glimmered on the table. The curtains of the bed were undrawn, and there—there lay gasping in the last convulsive agonies of nature—Oh, lady! she was dying—I rushed into the room, threw myself by her side, and implored her to live for me. She knew me—yes, she knew me—but at that very instant an officer with an armed party entered the apartment. They had watched me, and I was arrested as a deserter—arrested did I say? Ay! but not till I had stretched one of the insulting rascals at my feet. I was handcuffed, and bayonets were pointed at my breast. Vain was every entreaty for one hour, only one hour. The dying woman raised herself upon her pillow—she stretched forth her hand to mine, manacled as they were—she fell back, and Emma—yes, my Emma was no more. Despair, rage, fury, worked up the fiends within my soul! I struggled to burst my fetters, dashed them at all who approached me; but overcome at length, was borne to the common gaol. I was tried for desertion, and, on account of my resistance, was flogged through the fleet. I had acted improperly as a seaman, but I had done my duty as a man. It was not my intention to desert my ship, but my feelings overpowered me, and I obeyed their dictates. Yet now I felt indignant at my punishment, and took the first opportunity to escape; but whither could I go?—there was no protection for me. One visit, one lonely visit was paid to the grave of her who was now at rest for ever; and I again entered on board the –, bound to the West India station. I fought in several actions, and lost my arm. But the R* for desertion was still against my name, and though I obtained a pension for my wound, I could obtain none for servitude. I cannot apply to the friends of my youth, for they believe me dead; and who would credit the assertions of a broken-hearted sailor?—No, no: a few-short months, and the voyage of life will be over; then will old Will Jennings be laid in peace by the side of Emma Wentworth, and wait for the last great muster before Him who searches all hearts, and rewards those seamen who have done their duty." Here he ceased, while D– turned to his wife, whose loud sobs gave witness to the sympathy of her heart; but the agony increased to hysteric convulsions—she sprang hastily on her feet—shrieked, "'Tis he! 'tis William! 'tis my uncle!" and fell upon his neck!—Literary Magnet.