полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 364, April 4, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 364, April 4, 1829

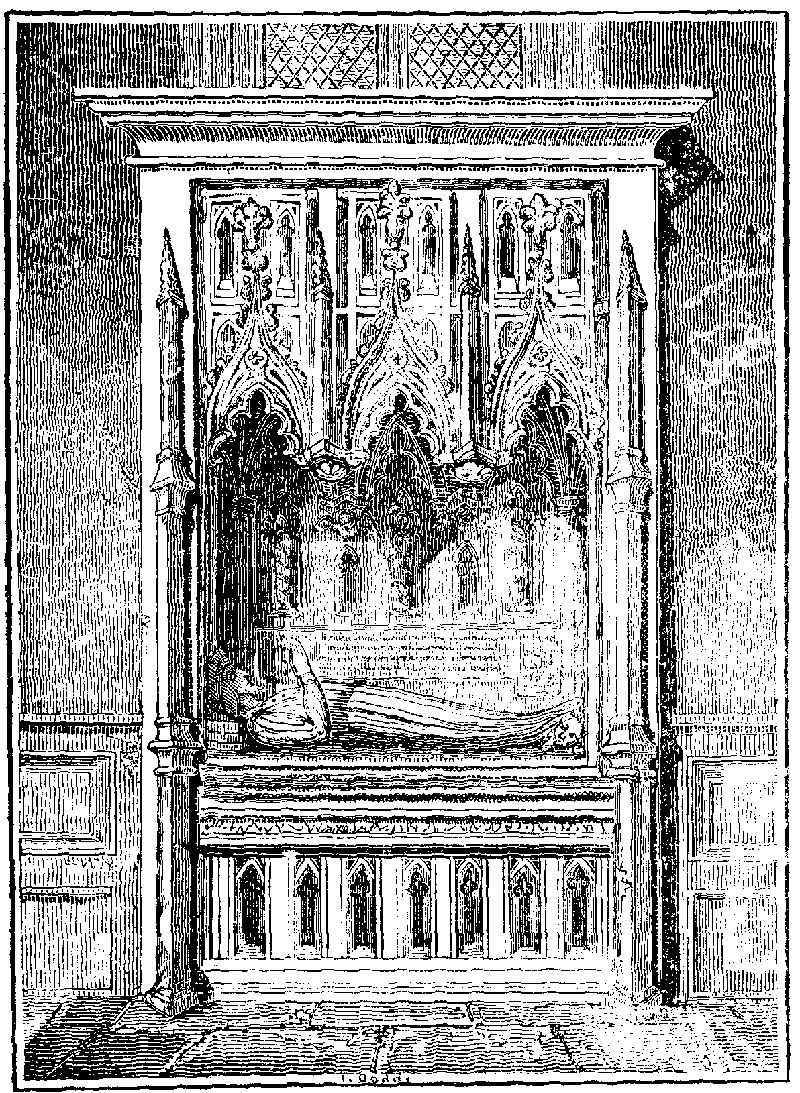

TOMB OF GOWER, THE POET

Tomb of Gower, the Poet.

Dr. Johnson has dignified Gower with the character of "THE FATHER OF ENGLISH POETRY"; so that no apology is required for the introduction of the above memorial in our pages. It stands in the north aisle of the church of St. Mary Ovrie, or St. Saviour, Southwark; and is one of the richest monuments within those hallowed walls. The tomb consists of three Gothic arches, the roof of which springs into several angles. The arches are richly ornamented with cinnquefoil tracery, roses, and carved work of exquisite character. Behind these arches are two rows of trefoil niches; and between them also rises a square column, of the Doric order, surmounted by carved pinnacles. On the extremity of the arches is placed richly carved foliage, of a similar character to that which ornaments the edges of the arches; and in the centre are circles enclosing quatrefoils. From the bases of the two middle square columns descend roses, and other foliage; and from the lower extremities of the interior arches descend cherubim. Within three painted niches, are the figures of Charity, Mercy, and Pity, round whom are entwined golden scrolls bearing the following inscriptions:

"Pour la Pitie Jesu regarde.Et tiens cest Ami en saufve Garde."Jesu! for thy compassion's sake look down,And guard this soul as if it were thine own.On the second scroll is written:

"Oh, bon Jesu! faite Mercy,Al' Ame dont le Corps gist icy."Oh! good Jesu! Mercy shewTo him whose body lies below.On the third scroll is written:

"En toy qui es Fitz de Dieu le Pere,Saufve soit qui gist sours cest Pierre."May he who lies beneath this stone,Be sav'd in thee, God's only son!1Between each of these figures are painted blank trefoil niches; and below the whole, on a plain tablet, the following inscription:

"Armiger scutum nihil a modo fut tibi tutum,Reddidit immolutum, morti generali tributum,Spiritus exutum se gaudeat esse solutum,Est ubi vistutum, Regnum sive labe statutum."On the left side:

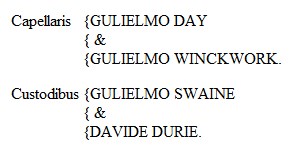

"Hoc viriInter inclytos memorandiMonumentum sepulchrali,Restaurari propriis impensisParocnia hujus meolæCuraveruntA.D. MDCCXCVIII."On the right side:

Capellaris {GULIELMO DAY

And below the effigy runs the following:—

"Hic jacet JOHANNIS GOWER,Armiger, Anglorum Poeta celeberrimus,ac huic sacro Edificio Benefactor, insignistemporibus Edw. III. et Rich. II."Here lieth John Gower, esq., a celebratedEnglish poet, also a benefactor tothis sacred edifice, in the time of EdwardIII. and Richard II.The base of the monument has seven trefoil niches, within as many plain-pointed ones.

The effigy of the poet is placed above, in a recumbent posture, beneath the canopy just described. He is dressed in a gown, originally purple, covering his feet, which rest on the neck of a lion. A coronet of roses adorns his head, which is raised by three folio volumes, labelled on their respective ends, "Vox Clamantis," "Speculum Meditantis," and "Confessio Amantis." Round the neck hangs a collar of SSS. Over the lion, on the side of the monument, are the arms of the deceased, hanging, by the dexter corner, from an ancient French chappeau, bearing his crest. The dress of this effigy has, probably, given rise to the conjectures concerning the rank in life which Gower maintained; but that is too precarious a ground on which to form a decided opinion on such a point.

Gower's arms are, Argent on a cheveron, azure, three leopard's heads, Or. Crest. On a chappeau turned up with ermine, a talbot, serjant, proper.

A little eastward of Gower's monument is part of a pillar, descending from the roof, with a conical base. It is said to be hollow, and has, indeed, somewhat the appearance of a narrow chimney flue.

A biographical outline of Gower may not be unacceptable. He is said by Leland to have descended from a family settled at Sittenham, in Yorkshire. He was liberally educated, and was a member of the Inner Temple; and some have asserted that he became Chief Justice of the Common Pleas; but the most general opinion is that the judge was another person of the same name. It is certain that Gower was a person of considerable weight in his time; even had he not given such ample proofs of his wealth and munificence in rebuilding the conventual church of St. Mary Ouvrie, If he did not actually rebuild the church, as has been asserted, it is well known that he contributed very largely to that undertaking. Perhaps the only fact in detail which it is now possible to ascertain with certainty is, that he founded a chantry in the chapel of St. John, now the vestry.

Gower is supposed to have been born before Chaucer, who flourished in the early part of the fourteenth century, and is believed to have contracted an acquaintance with Gower during his residence in the Middle Temple. Chaucer himself, after his travels on the continent, became a student of the Inner Temple. The contiguity of these inns of court, the similarity of their studies and pursuits, and particularly, as they both possessed the same political bias; Chaucer attaching himself to John of Ghent, Duke of Lancaster, by whom, as well as by the Duchess Blanche, he was greatly esteemed; and Gower giving his influence to Thomas of Woodstock, both uncles to King Richard II.—would naturally produce a considerable degree of friendship and esteem between the two poets.

Gower did not long survive his friend Chaucer. In the first year of the reign of Henry IV. he appears to have lost his sight; but whether from accident or from old age (for he was then greatly advanced in years) is not known. This misfortune happened but a short period before his death, which took place in the year 1402, about nine years after he had completed the "Confessio Amantis," a work from whence he derived the honour of being ranked among the English poets.

The "Confessio" of Gower is said to have owed its origin to a request made to the poet by King Richard II.; who, accidentally meeting Gower on the Thames, called him into the royal barge, and enjoined him "to booke some new thing." This, therefore, was not the first of his poetical productions, though it is universally admitted to have been his chief, and that on which his principal reputation depends; and into which "it seems to have been his ambition to crowd all his erudition." It is, however, the last of the volumes, the titles which are painted on his monument in this church, and is supposed to be the last he ever wrote, at least of any important extent.

The poetical histories of Gower and Chaucer are intimately connected; yet there is a remarkable difference of opinion and pursuit in their respective writings. It must be confessed that to Chaucer, and not to Gower, should be applied the flattering appellation of "the father of our poetry;" though, as Johnson says, he was the first of our authors who can be said to have written English. To Chaucer, however, are we indebted for the first effort to emancipate the British muse from the ridiculous trammels of French diction, with which, till his time, it had been the fashion to interlard and obscure the English language. Gower, on the contrary, from a close intimacy with the French and Latin poets, found it easier to follow the beaten track. His first work was, therefore, written in French measure, and is entitled "Speculum Meditantis." There are two copies of this book now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. It contains ten books, and consists of a collection of precepts and examples, compiled from various authors, recommending the chastity of the marriage bed.

Gower's next work was a Latin production, entitled, "Vox Clamantis," of which there are many copies still extant. The unfortunate reign of the poet's royal patron, and the rebellion of Wat Tyler, furnished Gower with ample materials for this publication.—The "Confessio Amantis" was first printed in the year 1403, by Caxton.

There is a MS. in Trinity College, Cambridge, consisting of several small poems by Gower; but they are nearly destitute of merit. The French sonnets, however, of which there is a volume in the Marquess of Stafford's library, are spoken of by Mr. Warton, who has given a long account of them, with specimens, as possessing more merit.

The "Boke of Philip Sparrow," by the witty, but obscene Skelton, who wrote towards the close of the fifteenth century, says that "Gower's Englishe is old;" but the learned Dean Collet, in the early part of the succeeding century, studied not only Gower, but Chaucer, and even Lydgate, in order to improve and correct his own style. By the close of that century, however, the language of these writers was become entirely obsolete.

The "Confessio Amantis" was printed, a second time, by Barthelet, in the year 1532; a third time in 1544; a fourth in 1554; and, lastly, in a very correct and worthy manner, in the year 1810, under the judicious inspection of Dr. Chalmers.

It were ungrateful to withhold from Gower some acknowledgment of the share he had in producing a beneficial revolution in the English language; as it would be absurd and untrue to attribute to him any great degree of praise, as an inventor in that important work.

The church of St. Saviour was founded before the conquest, but was principally rebuilt in the fourteenth century, since which time it has undergone many extensive reparations at different periods. The tower, which is surmounted by four pinnacles, was repaired in 1818 and 1819; and the choir has been recently restored in conformity with the original design, under the superintendence of that indefatigable architect, Mr. George Gwilt.2 The dramatists, Fletcher and Massinger were buried in this church in one grave; and from the tower, Hollar drew his Views of London, both before and after the fire.

Besides the tomb of Gower, there are monuments to Launcelot Andrews, Bishop of Winchester; Richard Humble, Alderman of London, erected in 1616; and several others. Gower's monument was once very splendid, but its present state is not very indicative of the gratitude of the parish in which he perpetuated his munificence by erecting one of the finest churches in the metropolis.

In 1737, so slight and infrequent was the intercourse betwixt London and Edinburgh, that men still alive (1818) remember that upon one occasion the mail from the former city arrived at the General Post-Office in Scotland, with only one letter in it—Scott's Novels.

A SECOND CHAPTER ON KISSING

BY A NOVICE IN THE ART

(For the Mirror.)—–Our first fatherSmiled with superior love, as JupiterOn Juno smiles, when he impregns the clouds,That shed May flowers, and pressed her matron lipWith kisses pure. Par. Lost, b. 4, 1. 499—502.—–Kissing the world begun,And I hope it will never be doneOld Song.Kissing has been practised in various modes, and for various purposes, from a period of very remote antiquity. Among the ancient oriental nations, presents from a superior were saluted by kissing, to express gratitude and submission to the person conferring the favour. Reference is made to this custom, Genesis, ch. xl. v. 41, "According to thy words shall my people be ruled;" or, as the margin, supported by most eminent critics, renders it, "At thy mouth shall my people kiss." The consecration of the Jewish kings to the regal authority was sealed by a kiss from the officiator in the ceremony: 1 Sam. ch. x. v. 1. Kissing was also employed in the heathen worship as a religious rite. Cicero mentions a statue of Hercules, the chin and lips of which were considerably worn by the repeated kissing of the worshippers. When too far removed to be approached in this manner, it was usual to place the right hand upon the statue, and return it to the lips. That traces of these customs remain to the present day, kissing the Testament on oath in our courts of judicature, and kissing the hand as a respectful salute, afford sufficient evidence. But it is with kissing as a mode of expressing affection or endearment that we are principally concerned, and its use, as such, is of equal (perhaps greater) antiquity with any of the preceding usages. To the passage cited, MIRROR, No. 357, by Professor Childe Wilful, on this subject, may be added the meeting of Telemachus and Ulysses on the return of the latter from Troy, as described, Odyssey, lib. 16, v. 186—218; and the history of the courtship of the patriarch Jacob and the "fair damsel" Rachel, Genesis, ch. xxix. v. 11. This last authority, though it must be acknowledged not so classical as the foregoing, is nevertheless much more piquant, being perhaps the oldest record of amorous kissing extant. Thou seest, therefore, courteous reader, that this "divine custom," in addition to the claims upon thee which it intrinsically possesseth, and which are neither few nor small, hath moreover the universal suffrage of the highest antiquity; thou seest that its date, so far from being confined to the Trojan or Saxon age, can with certainty be traced to patriarchal times; yea, verily, and I cannot find it in me to rest here, without conducting thee to an era even more remote. Revert thine eye to the motto at the head of this chapter. Doth it not carry thee back in spirit to the very baby hours of creation, the "good old days of Adam and Eve?" and doth it not represent unto thee this delightful art as known and practised in full perfection, "when young time told his first birth-days by the sun?" I grant thee that such an authority is not sufficiently critical to fix with precision the "ab initio" of the custom; yet doth it not possess infinite claim upon thy credence? and more especially when thou considerest that, our respectable progenitors, the antediluvians, were visited with the deluge of waters for little else than their license. Vide chap. vi. of the first book of Moses called Genesis, passim. In a world, of which almost all we know with certainty is its uncertainty, and that "the fashion thereof passeth away," it is only a natural inquiry whether the custom of kissing hath, like most others, undergone any material alteration. Perhaps from its nature, it is as little subjected to versatility from the lapse of ages as any; yet still, to say that it has experienced some change, would not be hazarding a very improbable opinion. Who knows but the "clamorous smack" wherewith the Jehu of an eight-horse wagon salutes the lips of his rosy inamorata, (scarcely less audible than the crack of his heavy thong on Smiler's dull sides,) may have been perfectly consistent with the acmé of politesse some centuries bygone. We speak here somewhat confidently. Hear what an amorous votary of the Muses in the olden time, Robert Herrick, saith with respect to kissing:—.

"Pout your joined lips—then speak your kiss."If this were the present orthodox creed of kissing, it would most woefully spoil the sport of many a gallant youth, who, with the most polite officiousness, extinguishes (by pure accident of course) while professing to snuff, the candles, only that he may snatch a hasty, unobserved kiss of the smiling maiden, whose proximity hath so irresistibly tempted him. I wish the professor who hath already obliged us with a chapter on kissing, would lay us under greater and more manifold obligations, by a course of lectures on the same subject; and if I laid wagers, I would wager my judgment to a cockle-shell, that Socrates' discourse on marriage did not produce a more beneficial effect than would his lecture; and that few untasted lips would be found, either among his auditors, or those whose fortune it should be to fall in the way of those auditors; but as it is at present, (for, alas! these are not the days of Polydore Virgil or Erasmus,) we are compelled, albeit somewhat grumblingly, to be content with but a very limited share of such blisses. Not that I doubt (heaven forbid that I should) the real inclination or the ability of at least the juvenile part of my fair countrywomen to be much more liberal than they generally are in this way; but, "dear, confounded creatures," as Will Honeycomb says, what with the trammels of education and domestic restraint, they are prevented from appearing, as they "really are, the best good-natured things alive." So much innocent hypocrisy, so much mauvaise honte, so many of "the whispered no, so little meant," that they are practical antitheses to themselves. "Can danger lurk within a kiss." But all fathers are not Coleridges, nor are all mothers Woolstonecrafts.

I plead not for libertinism, though only in so simple and innocent a form as kissing. I do not long for the repetition (or more properly commencement) of Polydore Virgil's days of "promiscuous" kisses. Let these remain, as heretofore, in fiction, and in fiction alone. "A glutted market makes provisions cheap," saith Pope. True, saith experience.

"–The lip that all may press,Shall never more be pressed by mine,"saith Moore. Sic ego. But there is a medium to be observed between gluttony and absolute starvation, and "medio tutis-simus ibis," saith the proverb; and I do beg to tell those over cautious ladies and gentlemen, who seem to know no medium between the cloistered nun and the abandoned profligate, that Nature will prevail in their spite, or, as Obadiah wisely and truly said, "When lambs meet they will play." And now, reader, kind, courteous, gentle, or whatever thou art, I bid thee adieu, with the hope, that if we agree at this, we may meet again on some future occasion. IOTA.

THE SKETCH-BOOK

THE GAY WIDOW

A Leaf from the Reminiscences of a Collegian(For the Mirror.)Why she came to the university was best known to herself. I cannot bring myself always to analyze the motives of people's actions; and if Mrs. Welborn really desired, in lieu of acting mamma to children she did not possess, to play the part of gouvernante to a couple of wild, uncouth lads, (her nephews,) during their residence in college, it speaks much for her good nature, at all events. They were not, I believe, grateful for the means she adopted to display this amiable trait in her disposition, nor did people in general appreciate it as they surely ought to have done. Ill nature—and there is often a frightful preponderance of that quality in a small town—did not hesitate to assert that the widow Welborn's motive for pitching her tent amid scholastic shades was in toto a selfish one; even that of a design, if she could but accomplish it, of adding another self to self. I dare not, in this era of refinement, speak plainer, but will take for granted that I am understood. The widow Welborn, or, as she was more commonly termed. "The gay Widow" from certain gregarious propensities, resided with a couple of female servants in a small house, situated in the most public street of the town; which I know, for this reason,—the principal court of our college was opposite to it, and its gateway was the approved lounge, from morning till night, of the most idle and impudent amongst us. Various were the surmises as to who, what, and from whence the gay widow was; by many she was supposed to be immensely rich; and by a few, some lady of quality incog. Many, however, asserted, that her jewels were glass; her gold, tinsel, and her glittering ornaments, beads sewed upon pasteboard. Nevertheless, in the very face of this shameful detraction, to her delightful little soirées flocked the best families in the town, (there were not many,) the heads of houses, (scarcely room had they in her mansion for their bodies,) and many a, fellow, senior and junior, of many a college in–. I had the honour of attending sometimes at these parties, of which all that I remember at present is, that the sugar was nipped into pieces so small, as to oblige those who liked their tea sweet to put in two or three spoonsfull, instead of an equal quantum of lumps, to the astonishment and visible dismay of the waiters. There was generally, too, a sad deficiency in cake; and, oh! when the negus was handed round,–Well, perhaps her nephews drew largely upon her stock of wine; or the widow possibly thought her young men got too much of that commodity in our parties, and therefore needed it less in her own. As to the senior members of the university, I never could comprehend the reasons that induced their endurance of such an aqueous beverage. Sometimes I have attributed their visits to Mrs. Welborn's merely to a ramification of that system of espionage which she thought proper to employ upon her nephews, and they to extend indiscriminately towards every undergraduate; whereas being myself a well-intentioned, modest young man, mine own honour has seemed grievously insulted; but again, may not vanity, the hope, paramount in the breast of every individual, of being admired by "a fortune," have influenced these old gentlemen to swallow lukewarm potations, (minus wine, lemon, and sugar,) which were a kind of nutmeg broth? I can certainly aver, that old Rightangle, of our college, was, or pretended to be, desperately enamoured with the gay widow; indeed, his doleful looks at one period, and his shyness of the fair lady in question, were to me pretty evident proofs that he had made her an offer, which had been rejected. The gossips of – had long set it down as a match, but were, it seems, doomed to be disappointed of their cake and wine. I honestly believe that the widow hated Rightangle; and conscientiously declare, to the best of my knowledge, that her antipathy towards my very excellent tutor arose from the circumstance of his having a large red nose, and winning her money whenever they played at the same card-table. Strange stories were afloat respecting the menage of Mrs. Welborn; my bed-maker affirmed, upon her (?) honour and veracity, that a lady and gentleman, who had favoured her with a visit, had quitted her residence thrice thinner than they were when they entered it; and that a gentleman had hastily departed from the shelter of her hospitable roof, upon her refusing him the indulgence of a Welsh rabbit at breakfast! These, and similar tales, were promulgated by the treacherous industry of the widow's maid-servants. Mrs. Welborn was fond of claiming an intimate acquaintance with people of rank. I never, however, met any titled person at her house. She was a kind of living peerage, and an animated chronicle of the actions of the great, virtuous and vicious: but, if the truth must be spoken,—and in a private memoir, why conceal it?—she had acquaintances of a grade far inferior! I say not that I saw it, because I was never accustomed to lounge at our college gate; but the men that were most frequently there, insist that they have many times beheld the gay widow steal forth in the dusk of the evening, dressed as for a party, and have tracked her to the house of a haberdasher in the vicinity! Well! she is married now, and is Mrs. Welborn—the gay widow no longer. How she accomplished this affair I know not; it broke like a thunder-clap upon the ears of the good people of—. Suddenly, the widow was gone—her house and furniture were sold—the happy event was announced in the papers—no cake was sent out—so the gossips were disappointed; and as I have since learnt, that the lady has thrice undergone a separation from her husband, I imagine that she must have been so likewise.

M. L. B.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE SORROWS OF ROSALIE,

A TaleThis beautiful little volume has, in less than six months, reached a fourth edition, which is to us a proof that the readers of the present day know how to discriminate pure gold from pinchbeck or petit or, and intense, natural feeling from the tinsel and tissues of flimsy "poetry." The booksellers, nevertheless, say that poetry is unsaleable, and they are usually allowed to speak feelingly on the score of popularity and success. Yet within a very short time, we have seen a splendid poem—the "Pelican Island," by (the) Montgomery; the "Course of Time," a Miltonic composition, by the Rev. Mr. Pollock; and now we have before us a poem, of which on an average, an edition has been sold in six weeks. The sweeping censure that poems are unsaleable belongs then to a certain grade of poetry which ought never to have strayed out of the album in which it was first written, except for the benefit of the stationer, printer, and the newspapers. Nearly all the poetry of this description is too bizarre, and wants the pathos and deep feeling which uniformly characterize true poetry, and have a lasting impression on the reader: whereas, all the "initial" celebrity, the honied sweetness, lasts but for a few months, and then drops into oblivion.