полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 542, April 14, 1832

"Friday, June 25th.—The most remarkable object which we saw on rising this morning, was a rugged and romantic range of hills, appearing to the eastward of our encampment; it is called Engarskie, from a country of the same name in which the hills are situated, and which was formerly an independent kingdom, but is now become a province of Yàoorie. At a little before seven, A.M., our canoe was pushed off the sandy beach on which it had been secured last evening, and propelled down a very narrow channel, between a large sand-bank and the shore. This conducted us into the main branch of the Niger, and we again admired its delightful and magnificent appearance.

"We had proceeded only a few hundred yards when the river gradually widened to two miles, and continued so as far as the eye could reach. It looked very much like an artificial canal; the banks having the appearance of a dwarf wall, with vegetation beyond. In most places the water was extremely shallow, but in others it was deep enough to float a frigate. During the first two hours of the day, the scenery was as interesting and picturesque as can be imagined. The banks were literally covered with hamlets and villages; fine trees, bending under the weight of their dark and impenetrable foliage, everywhere relieved the eye from the glare of the sun's rays, and, contrasted with the lively verdure of the little hills and plains, produced the most pleasing effect. Afterwards, however, there was a decided change; the banks, which before consisted of dark earth, clay, or sand, were now composed of black rugged rocks; large sand-banks and islands were scattered in the river, which diverted it into a variety of little channels, and effectually destroyed its appearance.

"We had heard so unfavourable an account of the state of the river at one particular place which we should have to pass, that our people were compelled to disembark and walk along the banks a considerable way till we had passed it, when we took them in again. We found the description to be in no wise exaggerated; it presented a most forbidding appearance, and yields only to the state of the Niger near Boossà in difficulty and danger. On our arrival at this formidable place, we discovered a range of black rocks running directly across the stream, and the water, finding only one narrow passage, rushed through it with great impetuosity, over-turning and carrying away everything in its course. Our boatmen, with the assistance of a number of the natives, who planted themselves on the rocks on each side of the only channel, and in the stream at the stern of the canoe, lifted it by main force into smoother and safer water. The last difficulty with respect to rocks and sand-banks was now overcome, and in a very little time we came to the termination of all the islands, after which, it is said, there is not a single dangerous place up the Niger. The river here presented its noblest appearance; not a single rock nor sand-bank was anywhere perceptible; its borders resumed their beauty, and a strong, refreshing breeze, which had blown during the whole of the morning, now gave it the motion of a slightly-agitated sea. In the course of the morning we passed two lovely little islands, clothed in verdure, which at a short distance looked as charming as the fabled gardens of Hesperia; indeed no spot on earth can excel them in beauty of appearance. These islands are inhabited by a few individuals."

Upon leaving Yàoorie, a venerable Arab chief pretended great regard for the travellers, though he used them deceitfully; they had, however, "enjoyed an innocent kind of revenge, in administering to him a powerful dose of medicine, which though harmless in its effects, had yet been very troublesome to him. Indeed, it was not till we had 'jalaped' the sultan, his sister, and all the royal family, that we were permitted to take our farewell of Yàoorie."

The incident of physicking the royal family at Yàoorie by way of leave-taking, is only equalled by the following oddity:—"The captain of the palm oil brig, Elizabeth, now in the Calabar river, actually white-washed his crew from head to foot, while they were sick with fever and unable to protect themselves; his cook suffered so much in the operation, that the lime totally deprived him of the sight of one of his eyes, and rendered the other of little service to him."

The account of the Travellers' visit to Fernando Po, in the third volume, will be read with interest, as indeed will every page of the whole narrative; and to this commendation of the Messrs. Landers' Journal of their past adventures we cheerfully add our best wishes for the success of their future enterprize.

SONGS OF THE GIPSIES

Among the musical novelties of the day, we notice with much pleasure, a pretty volume of Lyrics, written by Mr. Moncrieff, the music by Mr. S. Nelson. The poetry is throughout sparkling and characteristic, and "an Historical Introduction on the origin and customs of Gipsies," prefixed to the Songs, is so attractive as to be likely to share the popularity of the piano-forte accompaniments. It is written with considerable care and neatness, and the peculiar tact requisite to produce an interesting paper on a dry subject.

We are only enabled to quote from the lyrics, an opening carol, as

Liberty, liberty!Search the world round,'Tis with the GipsyAlone thou art found.Then in the gay greenwoodWe worship thee now,The free, oh the free!Still live under the bough.Trarah! Trarah!Hark, the deep dingles ring,Free hearts, with the birdAnd the deer are on wing;Joy claims in the greenwoodThe Gipsy's glad vow,The blithe, oh the blithe!Still live under the bough.And the first song entire.

THE GIPSY QUEEN

Oh! 'tis I am the Gipsy Queen!And where is there queen like me,That can revel upon the green,In boundless liberty?What though my cheek be brown,And wild my raven hair,A red cloth hood my crown,And my sceptre the wand I bear!Yet, 'tis I am the Gipsy Queen!With my kingdom I'm well content,Though my realm's but the hawthorn glade;And my palace a tatter'd tentBeneath the willow's shade:Though my banquet I'm forc'd to makeOn haws and berries store,And the game that by chance we takeFrom some neighbouring hind's barn door!Yet, 'tis I am the Gipsy Queen!'Tis true I must ply my art,And share in my subjects' toils;But of all their gains I've part,I've the choice of all their spoils;And, by love and duty led,Ere from my jet black eyeOne sad tear should be shed,A thousand hearts would die!For, 'tis I am the Gipsy Queen!A SONG OF PITCAIRN'S ISLAND

Come, take our boy, and we will goBefore our cabin door;The winds shall bring us, as they blow,The murmurs of the shore;And we will kiss his young blue eyes,And I will sing him as he lies,Songs that were made of yore:I'll sing, in his delighted ear,The island-lays thou lov'st to hear.And thou, while stammering I repeat,Thy country's tongue shalt teach;'Tis not so soft, but far more sweetThan my own native speech;For thou no other tongue didst know,When, scarcely twenty moons ago,Upon Tahité's beach,Thou cam'st to woo me to be thine,With many a speaking look and sign.I knew thy meaning—thou didst praiseMy eyes, my locks of jet;Ah! well for me they won thy gaze—But thine were fairer yet!I'm glad to see my infant wearThy soft blue eyes and sunny hair,And when my sight is metBy his white brow and blooming cheek,I feel a joy I cannot speak.Come talk of Europe's maids with me,Whose necks and cheeks, they tell,Outshine the beauty of the sea,White foam and crimson shell.I'll shape like theirs my simple dress,And bind like them each jetty tress,A sight to please thee well;And for my dusky brow will braidA bonnet like an English maid.Come, for the soft, low sunlight calls—We lose the pleasant hours;'Tis lovelier than these cottage walls—That seat among the flowers.And I will learn of thee a prayerTo Him who gave a home so fair,A lot so blest as ours—The God who made for thee and meThis sweet lone isle amid the sea.From a volume of American Poetry, William Cullen Bryant.

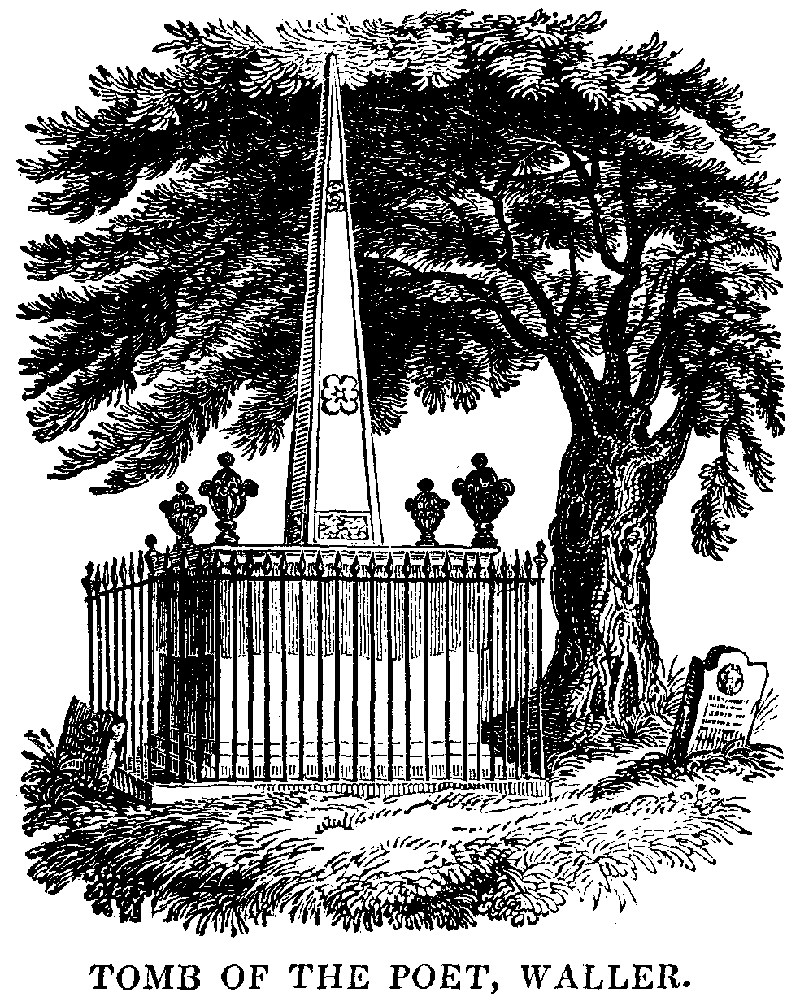

In the churchyard of Beaconsfield, Bucks, stands the above handsome tribute to the memory of the celebrated poet and politician, EDMUND WALLER. The monument is of marble, with a pyramid rising from the centre, and a votive urn at each corner. On the east side is a Latin inscription, stating that Waller was born March 30, 1605, at Coleshill, in Hertfordshire; his father being Robert Waller, Esq. (of Agmondelsham in Buckingham, whose family was originally a branch of the Kentish Wallers, 5 ) and his mother of the Hampden family; that he was a student at Cambridge; "his first wife was Anne, only daughter and heiress to Edward Banks, twice made a father by his first wife, and thirteen times by his second, whom he survived eight years; he died October 21, 1687." The original inscription is by Rymer, and is to be seen in most editions of the poet's works. The monument was erected by the poet's son's executors, in 1700, and stands on the east side of the churchyard, near the family vault. The above engraving is from a sketch, obligingly furnished by our Correspondent, W.H. of Wycombe.

Waller was proprietor of the manor of Beaconsfield, and that of Hall Barn, in the vicinity, at which latter place he resided.

It is remarkable, that this great man, toward the decline of life bought a small house, with a little land, on his natal spot; observing, "that he should be glad to die like the stag, where he was roused." This, however, did not happen. "When he was at Beaconsfield," says Johnson, "he found his legs grow tumid: he went to Windsor, where Sir Charles Scarborough then attended the king, and requested him, as both a friend and physician, to tell him what that swelling meant. 'Sir,' answered Scarborough, 'your blood will run no longer.' Waller repeated some lines of Virgil, and went home to die. As the disease increased upon him, he composed himself for his departure; and calling upon Dr. Birch to give him the holy sacrament, he desired his children to take it with him, and made an earnest declaration of his faith in Christianity. It now appeared what part of his conversation with the great could be remembered with delight. He related, that being present when the Duke of Buckingham talked profanely before King Charles, he said to him, 'My lord, I am a great deal older than your Grace, and have, I believe, heard more arguments for atheism than ever your Grace did; but I have lived long enough to see there is nothing in them, and so I hope your Grace will."

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

TROUT TICKLING IN IRELAND

What will our ticklish correspondent, W.H.H. say to this?

"Kniveing trouts" (they call it tickling in England) is good sport. You go to a stony shallow at night, a companion bearing a torch; then stripping to the thighs and shoulders, wade in; grope with your hands under the stones, sods, and other harbourage, till you find your game, then grip him in your "knieve," and toss him ashore.

I remember, when a boy, carrying the splits for a servant of the family, called Sam Wham. Now Sam was an able young fellow, well-boned and willing; a hard headed cudgel player, and a marvellous tough wrestler, for he had a backbone like a sea-serpent; this gained him the name of the Twister and Twiner. He had got into the river, with his back to me, was stooping over a broad stone, when something bolted from under the bank on which I stood, right through his legs. Sam fell with a great splash upon his face, but in falling, jammed whatever it was against the stone. "Let go, Twister," shouted I, "'tis an otter, he will nip a finger off you."—"Whisht," sputtered he, as he slid his hand under the water; "May I never read a text again, if he isna a sawmont wi' a shouther like a hog!"—"Grip him by the gills, Twister," cried I.—"Saul will I!" cried the Twiner; but just then there was a heave, a roll, a splash, a slap like a pistol-shot; down went Sam, and up went the salmon, spun like a shilling at pitch and toss, six feet into the air. I leaped in just as he came to the water; but my foot caught between two stones, and the more I pulled the firmer it stuck. The fish fell in a spot shallower than that from which he had leaped. Sam saw the chance, and tackled to again: while I, sitting down in the stream as best I might, held up my torch, and cried fair play, as shoulder to shoulder, throughout and about, up and down, roll and tumble, to it they went, Sam and the salmon. The Twister was never so twined before. Yet through crossbuttocks and capsizes innumerable, he still held on; now haled through a pool; now haling up a bank; now heels over head; now head over heels; now head and heels together; doubled up in a corner; but at last stretched fairly on his back, and foaming for rage and disappointment; while the victorious salmon, slapping the stones with his tail, and whirling the spray from his shoulders at every roll, came boring and snoring up the ford. I tugged and strained to no purpose; he flashed by me with a snort, and slid into the deep water. Sam now staggered forward with battered bones and peeled elbows, blowing like a grampus, and cursing like nothing but himself. He extricated me, and we limped home. Neither rose for a week; for I had a dislocated ankle, and the Twister was troubled with a broken rib. Poor Sam! he had his brains discovered at last by a poker in a row, and was worm's meat within three months; yet, ere he died, he had the satisfaction of feasting on his old antagonist, who was man's meat next morning. They caught him in a net. Sam knew him by the twist in his tail.—Blackwood's Magazine.

DIAMONDS IN BRAZILThe operation of working for these precious jems is a very simple one. The alluvial soil (the cascalhao) is dug up from the bed of the river, and removed to a convenient spot on the banks for working. The process is as follows:—a rancho is erected about a hundred feet long, and half that distance in width; down the middle of the area is conveyed a canal, covered with earth; on the other side of the area is a flooring of planks, about sixteen feet in length, extending the whole length of the shed, and to which an inclined direction is given; this flooring is divided into troughs, into which is thrown a portion of the cascalhao; the water is then let in, and the earth raked until the water becomes clear; the earthy particles having been washed away, the gravel is raked up to the end of the trough; the largest stones are thrown out, and afterwards the smaller ones, the whole is then examined with great care for diamonds. When a negro finds one, he claps his hands, stands in an erect posture, holding the diamond between his fore-finger and thumb; it is received by one of the overseers posted on lofty seats, at equal distances, along the line of the work. On the conclusion of the work, the diamonds found during the day are weighed, and registered by the overseer en chef. If a negro has the good fortune to find a stone weighing upwards of seventeen carats, he is immediately manumitted, and for smaller stones proportionate premiums are given. There are, besides, several other works on this river, and on other streams, but the supply of diamonds falls now considerably short of former periods, and their produce scarcely defrays the expenses.

The Diamond District of the Serro do Frio is about twenty leagues in length, and nine in breadth; the soil is barren, but intersected by numerous streams. It was first discovered by some miners, shortly after the establishment of the Villa do Principe. In working for gold in the rivulets of Milho Verde and St. Goncalzes, they discovered some pebbles of geometric form, and of a peculiar hue and lustre. For some years these pebbles were given as pretty baubles to children, or used as counters for marking the points of their favourite game of voltarete. At last an officer, who had been some years at Goa, in the East Indies, arrived in the Commarca: he was struck with the peculiar form of these pebbles, and from several experiments he made, it struck him that they were diamonds. He immediately collected a few, and sent them to Holland, where, to the astonishment of the lapidaries, they were found to be brilliants of the finest water. It will easily be imagined, that on the arrival of this intelligence in Brazil, the hitherto despised counters suddenly became the objects of universal research, and almost immediately disappeared.

The government of Portugal now issued a decree, declaring all diamonds a monopoly of the crown. For a length of time it was considered that diamonds were confined solely to the district of Serro Frio. But this is an error; they are found in almost every part of the empire, particularly in the remote provinces of Goyazes and Matto Grosso, where there exist several districtos diamantescos. These gems have been even found on the tops of the highest mountains; indeed, it is the opinion of the Brazilian mineralogists that the original diamond formations are in the mountains, and that they will one day or other be discovered in such quantities, as to render them objects of comparatively small value.

The largest diamond in the world was found in the river Abaite; about ninety-two leagues to N.W. of Serro do Frio. The history of its discovery is romantic:—three Brazilians, Ant. de Souza, Jose Felix Gomes, and Thomas de Souza, were sentenced, for some supposed misdemeanour, to perpetual banishment in the wildest part of the interior. Their sentence was a cruel one; but the region of their exile was the richest in the world; every river rolled over a bed of gold, every valley contained inexhaustible mines of diamonds. A suspicion of this kind enabled these unfortunate men to support the horrors of their fate; they were constantly sustained by the golden hope of discovering some rich mine, that would produce a reversion of their hard sentence. Thus they wandered about for nearly six years, in quest of mines; but fortune was at last propitious. An excessive draught had laid dry the bed of the river Abaite, and here, while working for gold, they discovered a diamond of nearly an ounce in weight. Overwhelmed with joy at this providential discovery, they resolved to proceed, at all hazards, to Villa Rica, and trust to the mercy of the crown. The governor, on beholding the magnitude and lustre of the gem, could scarcely credit the evidence of his senses. He immediately appointed a commission of the officers of the Diamond District to report on its nature; and on their pronouncing it a real diamond, it was immediately dispatched to Lisbon. It is needless to add that the sentence of the three "condemnados" was immediately reversed.

This celebrated diamond has been estimated by Romé de l'Isle at the enormous sum of three hundred millions sterling. It is uncut, but the late King of Portugal, who had a passion for precious stones, had a hole bored through it, in order to wear it suspended about his neck on gala days. No sovereign possessed so fine a collection of diamonds as this prince.—Monthly Mag.

NOTES OF A READER

AMERICAN LIFE

Mrs. Trollope's amusing book has furnished us with still another page or two of scenes and sketches:

Crocodiles on the Mississippi.

"It is said that at some points of this dismal river, crocodiles are so abundant as to add the terror of their attacks to the other sufferings of a dwelling there. We were told a story of a squatter, who having 'located' himself close to the river's edge, proceeded to build his cabin. This operation is soon performed, for social feeling and the love of whiskey bring all the scanty neighbourhood round a new comer, to aid him in cutting down trees, and in rolling up the logs, till the mansion is complete. This was done; the wife and five young children were put in possession of their new home, and slept soundly after a long march. Towards day-break the husband and father was awakened by a faint cry, and looking up, beheld relics of three of his children scattered over the floor, and an enormous crocodile, with several young-ones around her, occupied in devouring the remnants of their horrid meal. He looked around for a weapon, but finding none, and aware that unarmed he could do nothing, he raised himself gently on his bed, and contrived to crawl from thence through a window, hoping that his wife, whom he left sleeping, might with the remaining children rest undiscovered till his return. He flew to his nearest neighbour and besought his aid; in less than half an hour two men returned with him, all three well armed; but alas! they were too late! the wife and her two babes lay mangled on their bloody bed. The gorged reptiles fell an easy prey to their assailants, who, upon examining the place, found the hut had been constructed close to the mouth of a large hole, almost a cavern, where the monster had hatched her hateful brood."

Pig Scavengers.

"We were soon settled in our new dwelling, which looked neat and comfortable enough, but we speedily found that it was devoid of nearly all the accommodation that Europeans conceive necessary to decency and comfort. No pump, no cistern, no drain of any kind, no dustman's cart, or any other visible means of getting rid of the rubbish, which vanishes with such celerity in London, that one has no time to think of its existence; but which accumulated so rapidly at Cincinnati, that I sent for my landlord to know in what manner refuse of all kinds was to be disposed of.

"Your Help will just have to fix them all into the middle of the street, but you must mind, old woman, that it is the middle. I expect you don't know as we have got a law what forbids throwing such things at the sides of the streets; they must just all be cast right into the middle, and the pigs soon takes them off.'"

American English.

"I very seldom during my whole stay in the country heard a sentence elegantly turned, and correctly pronounced from the lips of an American. There is always something either in the expression or the accent that jars the feelings and shocks the taste."

Mr. Bullock.

"About two miles below Cincinnati, on the Kentucky side of the river, Mr. Bullock, the well known proprietor of the Egyptian Hall, has bought a large estate, with a noble house upon it. He and his amiable wife were devoting themselves to the embellishment of the house and grounds; and certainly there is more taste and art lavished on one of their beautiful saloons, than all Western America can show elsewhere. It is impossible to help feeling that Mr. Bullock is rather out of his element in this remote spot, and the gems of art he has brought with him, show as strangely there, as would a bower of roses in Siberia, or a Cincinnati fashionable at Almack's. The exquisite beauty of the spot, commanding one of the finest reaches of the Ohio, the extensive gardens, and the large and handsome mansion, have tempted Mr. Bullock to spend a large sum in the purchase of this place, and if any one who has passed his life in London could endure such a change, the active mind and sanguine spirit of Mr. Bullock might enable him to do it; but his frank, and truly English hospitality, and his enlightened and inquiring mind, seemed sadly wasted there. I have since heard with pleasure that Mr. Bullock has parted with this beautiful, but secluded mansion.

"Mr. Bullock was showing to some gentlemen of the first standing, the very élite of Cincinnati, his beautiful collection of engravings, when one among them exclaimed, 'Have you really done all these since you came here? How hard you must have worked!'"

Cows.

"These animals are fed morning and evening at the door of the house, with a good mess of Indian corn, boiled with water; while they eat, they are milked, and when the operation is completed the milk-pail and the meal-tub retreat into the dwelling, leaving the republican cow to walk away, to take her pleasure on the hills, or in the gutters, as may suit her fancy best. They generally return very regularly to give and take the morning and evening meal; though it more than once happened to us, before we were supplied by a regular milk cart, to have our jug sent home empty, with the sad news that 'the cow was not come home, and it was too late to look for her to breakfast now.' Once, I remember, the good woman told us that she had overslept herself, and that the cow had come and gone again, 'not liking, I expect, to hanker about by herself for nothing, poor thing.'"