полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 537, March 10, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 537, March 10, 1832

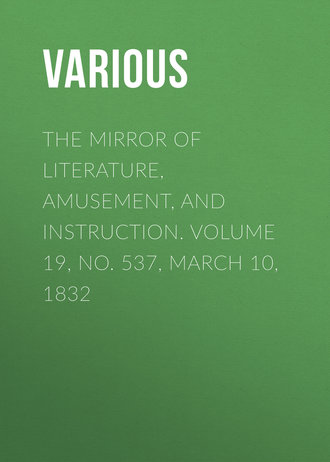

POLYNESIAN ISLANDS

TUCOPIA.

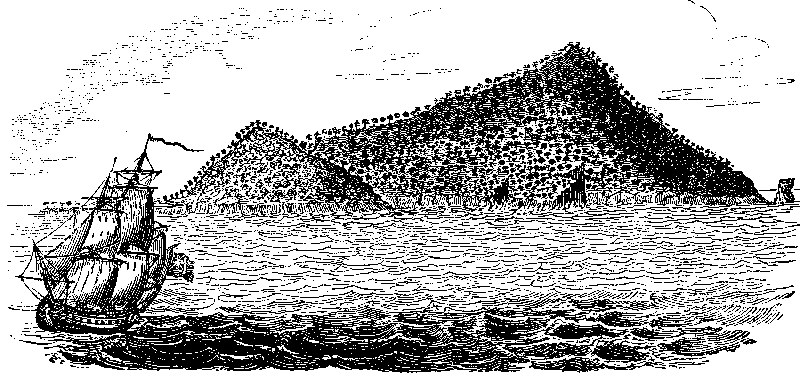

PIERCY ISLANDS.

Mr. George Bennett,1 whose "Journals" and "Researches" denote him to be a shrewd and ingenious observer, has favoured us with the original sketches of the above cuts. They represent three of the spots that stud the Southern Pacific Ocean. The first beams with lovely luxuriance in its wood-crowned heights; while the second and third rise from the bosom of the sea in frowning sterility amidst the gay ripple that ever and anon laves their sides, and plashes in the brilliancy of the sunbeam.

Tucopia, or Barwell's Island, has recently been elsewhere described by Mr. Bennett.2 His sketch includes the S.W. side of the island, and his entertaining description is as follows:

"This small but elevated and wooded island was discovered by the ship Barwell in 1798; it was afterwards (1810) visited by the French navigators, who called it by the native name Tucopia. On the S.W. side of the island is a wooded, picturesque valley, surrounded by lofty mountains, and containing a small but well-inhabited village. Two singularly isolated basaltic rocks, of some elevation, partially bare, but at parts covered by shrubs, rise from about the centre of the valley. When close in, two canoes came off containing several natives, who readily came on board; two of them had been in an English whaler, (which ships occasionally touched at the island for provisions, &c.) and addressed us in tolerable English. They were well formed, muscular men, with fine and expressive features, of the Asiatic race, in colour of a light copper; they wore the hair long, and stained of a light brown colour; they were tattooed only on the breast, which had been executed in a neat vandyked form; the ears, as also the septum narium, were perforated, and in them were worn tortoiseshell rings; around the waist was worn a narrow piece of native cloth (died either of a dark red or yellow colour), or a small narrow mat formed from the bark of a tree, and of fine texture; some of these had neatly-worked dark red borders, apparently done with the fibres of some dyed bark. They rub their bodies with scented cocoa-nut oil as well as turmeric. The canoes were neatly constructed, had outriggers, and much resemble those of Tongatabu; the sails were triangular, and formed of matting. No weapons were observed in the possession of any of the natives; they said they had two muskets, which had been procured in barter from some European ship. We landed on a sandy beach, and were received by a large concourse of natives. We were introduced to a grave old gentleman, who was seated on the ground, recently daubed with turmeric and oil for this ceremony; he was styled the ariki, or chief, of this portion of the island. On an axe, as well as other presents, being laid before him, he (as is usual among the chiefs of the Polynesian Islands on a ceremonial occasion) did not show any expression of gratification or dislike at the presents but in a grave manner made a few inquiries about the ship. Near the ariki sat a female, whose blooming days had passed; she was introduced as his wife; her head was decorated with a fillet of white feathers; the upper part of her body was exposed, but she wore a mat round the waist which descended to the ankles; the chief was apparently a man of middle age.

"The native habitations were low, of a tent form, and thatched with cocoa-nut leaves; these habitations were not regular, but scattered among the dense vegetation which surrounded them on all sides. The tacca pinnatifida, or Polynesian arrow-root plant, called massoa by the natives, was abundant, as also the fittou, or calophyllum inophyllum, and a species of fan palm, growing to the height of fifteen and twenty feet, called tarapurau by the natives; the areka palm was also seen, and the piper betel was also cultivated among them. They had adopted the oriental custom of chewing the betel; in using this masticatory they were not particular about the maturity of the nuts, some eating them very young as well as when quite ripe; they carried them about enclosed in the husk, which was taken off when used.3 At a short distance from the beech, inland, was a lake of some extent, nearly surrounded by lofty, densely-wooded hills. Some wild ducks were seen, and a gun being fired at them, the report raised numbers of the 'plumy tribe,' filling the air with their screams, alarmed at a noise to which they had been unaccustomed. Several native graves were observed, which were very neat; a stone was placed at the head and the grave neatly covered over by plaited sections of the cocoa-nut frond; no particular enclosures for the burial of the dead were observed. When rambling about, the 'timid female' fled at our approach. From a casual glimpse of the fair objects, they merit being classed among the 'beautiful portion of the creation;' their hair was cut close.

"Cooked yams, cocoa-nuts, &c. were brought us by the natives, and their manner was very friendly; of provisions, yams, hogs, &c. could be procured. The natives were anxious to accompany us on the voyage, and it was with the greatest difficulty that we could get rid of them. It seems they have occasional intercourse with islands at some distance from them; two fine polished gourds, containing lime, &c. used with their betel, were observed among them—one was plain and the other ornamented with figures, apparently burnt by some instrument. They stated that these had been procured from the island of Santa Cruz (Charlotte's Archipelago) by one of the chief's sons. Some of the natives were observed much darker than others, and there appeared a mixture of some races. Their numerals were as follows:—

"1 Tashi.

2 Rua.

3 Toru.

4 Fa.

5 Hima.

6 Ono.

7 Fithu.

8 Warru.

9 Hiva.

10 Tanga, foru."

The isolated basaltic rocks in the centre of the valley may give rise to some curious speculations on the origin of this island. It has long been decided that basaltic rocks are of igneous origin, in opposition to the theory of Werner—that they were deposited by the ocean on the summits of elevated mountains. May not the occurrence of these basalt rocks therefore illustrate the more immediate volcanic origin of Tucopia?

The second Cut represents the PIERCY ISLANDS, two barren islets situated a short distance off Cape Bret, (New Zealand,) near the entrance of the Bay of Islands: one is of very small size, and appears connected to the other by a ledge of rocks visible at low water. The larger one is quoin shaped, and has a remarkable perforation, seen in the sketch.

OLIVER GOLDSMITH

(For the Mirror.)One of the residences of this historian and poet, was about a mile from Paddington on the north side of the Edgware Road, near a place called Kilburn Priory; and the wooden cottage is still standing, although the land near it has been of late covered with newly-erected villas. It is occupied by a person in humble life, and is not to be altered or removed owing to the respect entertained for the memory of this remarkable literary character. In this cottage, Goldsmith wrote his admirable treatise on Animated Nature. A sketch of this rustic dwelling is a desideratum, as, in after days, it may be demolished to make way for modern improvement.

J.C.HSTANZAS

TO THE SPIRIT OF EVENING(For the Mirror.)Mild genius of the silent eve!Thy pathway through the radiant skies,Is the rich track which sunbeams weaveWith all their varied, mingling, dyes,Ere yet the lingering sun has fled,Or glory left the mountain's head.Yet not one ray of sunset's hueIllumes thy silent, peaceful train;And scarce a murmur trembles throughThe woods, to hail thy gentle reign,Save where the nightingale, afar,Sings wildly to thy lonely star.Yet gentlest eve, attending thee,Come meek devotion, peace, and rest,Mild contemplation, memory,And silence with her sway so blest;And every mortal wish and thought,By thee to holiest peace is wrought.Thine airs that crisp the quiet stream,Are soft as slumbering infants' breath:The trembling stars, that o'er thee beam,Are pure as Faith's own crowning wreath:And e'en thy silence has for meA charm more sweet than melody.Oh gentle spirit, blending allThe beauties parting day bestows,With deeper hues that slowly fall,To shadow Nature's soft repose;So sweet, so mild, thy transient sway,We mourn it should so soon decay.But like the loveliest, frailest thingsWe prize on earth, thou canst not last;For scarce thine hour its sweetness bringsTo soothe, and bless us, e'er 'tis past;And night, dull cheerless night destroysThy tender light, and peaceful joys.SYLVATRAVELLING NOTES IN SOUTH WALES

(To the Editor.)I observe a communication respecting my little note on the shrimp in one of your recent Numbers. Whether shrimps or not, I was not aware of my error, for they closely resembled them, and were not "as different as possible," as H.W. asserts. Every person too, must have remarked the agility of the old shrimp when caught. They were besides of various sizes, many being much larger that what H.W. means as the "sea flea." Perhaps H.W. will be good enough to describe the size of the latter when he sends his history of the shrimp.

With regard to the "encroachers," my information must have been incorrect. I had omitted, accidentally however, in the hurry of writing, to add "if undisturbed for a certain period," to the passage quoted in page 20 of your No. 529.

In North Wales, some years ago, there were some serious disturbances concerning an invasion of the alleged rights of the peasantry, but I do not now remember the particulars. Few things by the way, have been attended with more mischievous effects in England than the extensive system of inclosures which has been pursued within the last thirty years. No less than 3,000 inclosure acts have been passed during that period; and nearly 300,000 acres formerly common, inclosed: from which the poor cottager was once enabled to add greatly to his comfort, and by the support thus afforded him, to keep a cow, pigs, &c.

I attended a meeting at Exeter Hall, the other day, of the "Labourers' Friend Society," whose object is to provide the peasantry with small allotments of land at a low rent. This system, if extensively adopted, promises to work a wonderful change for the better in the condition of the working classes. Indeed the system where adopted has already been attended with astonishing results. When we come to consider that out of the 77,394,433 acres of land in the British Isles, there are no less than 15,000,000 acres of uncultivated wastes, which might be profitably brought under cultivation; it is surprising to us, that instead of applying funds for emigration, our legislators have so long neglected this all-important subject. Of the remaining 62,394,433 acres, it appears that 46,522,970 are cultivated, and 15,871,463 unprofitable land. The adoption of the allotment system has been justly characterized as of national importance, inasmuch as it diminishes the burdens of the poor, is a stimulus to industry, and profitably employs their leisure hours; besides affording an occupation for their children, who would otherwise, perhaps, run about in idleness.

In the reign of Elizabeth, no cottager had less than four acres of land to cultivate; but it has been found that a single rood has produced the most beneficial effects. We need scarcely add that where adopted, it has very greatly reduced the poor-rates. The subject is an interesting one, and, I trust, we shall in a short period hear of the benevolent and meritorious objects of the Society being extensively adopted. We refer the reader to some remarks on the subject in connexion with the Welsh peasantry, &c. in The Mirror, No. 505.

In our description of Swansea, in No. 465, we mentioned the facility with which the harbour could be improved, and the importance of adapting it for a larger class of shipping than now frequent that port. On a recent visit to South Wales, we found this improvement about to be carried into effect, and an act is to be obtained during the present session of Parliament. A new harbour on an extensive scale, is also about to be commenced near Cardiff. The increase of population in Wales has been very considerable since the census of 1821. Wales contains a superficies of 4,752,000 acres; of which 3,117,000 are cultivated; 530,000 capable of improvement, and 1,105,000 acres are unprofitable land.

VYVYANTHE SKETCH BOOK

SCOTTISH SPORTING

(Concluded from page 137.)But here come the graces of the forest, fifty at least in the herd—how beautifully light and airy; elegance and pride personified; onward they come in short, stately trot, and tossing and sawing the wind with their lofty antlers, like Sherwood oak taking a walk; heavens! it is a sight of sights. Now advance in play, a score of fawns and hinds in front of the herd, moving in their own light as it were, and skipping and leaping and scattering the dew from the green sward with their silvery feet, like fairies dancing on a moonbeam, and dashing its light drops on to the fairy ring with their feet of ether. O! it was a sight of living electricity; our very eyes seemed to shoot sparks from man to man, and even the monkey himself, as we gazed at each other in trembling suspense.

"Noo, here they coom wi' their een o' fire an' ears o' air," whispered the Ettric poet.

"Hush," quoth I, "or they'll be off like feathers in a whirlwind, or shadows of the lights and darks of nothingness lost in a poet's nightmare."

"A sumph ye mean," answered Jammie.

"Hush, there they are gazing in the water, and falling in love with their own reflected beauty."

"Mark the brindled tan buck," whispered one keeper to the other. They fired together, and both struck him plump in his eye of fire; mine seemed to drop sparks with sympathy: he bounded up ten feet high—he shrieked, and fell stone dead; Gods, what a shriek it was; I fancy even now I have that shriek and its hill-echo chained to the tympanum of my ear, like the shriek of the shipwrecked hanging over the sea—heavens! it was a pity to slay a king I thought, as I saw him fall in his pride and strength; but by some irresistible instinct, my own gun, pulled, I don't know how, and went off, and wounded another in the hip, and he plunged like mad into the river, to staunch his wounds and defend himself against the dogs. Ay, there he is keeping them at bay, and scorning to yield an inch backward; and now the keeper steals in behind him and lets him down by ham-stringing him: but when he found his favourite dog back-broken by the buck, why he cursed the deer, and begged our pardon for swearing; and now he cuts a slashing gash from shoulder to chop to let out the blood; and there lay they, dead, in silvan beauty, like two angels which might have been resting on the pole, and spirit-stricken into ice before they had power to flee away.

But we must away to Sir Reynard's hall, and unsough him; this we can do with less sorrowful feelings than killing a deer, which indeed, is like taking the life of a brother or a sister; but as to a fox, there is an old clow-jewdaism about him, that makes me feel like passing Petticoat-lane or Monmouth-street, or that sink of iniquity, Holy-well-street. O, the cunning, side-walking, side-long-glancing, corner-peeping, hang-dog-looking, stolen-goods-receiving knave; "Christian dog" can hold no sympathy with thee, so have at thee. Ah, here is his hold, a perfect Waterloo of bones.

"The banes o' my bonnie Toop, a prayer of vengeance for that; an' Sandy Scott's twa-yir-auld gimmer, marterdum for that." "An' my braxsied wether," quoth a forester; "the rack for that, and finally the auld spay-wife's bantam cock, eyes and tongue cut out and set adrift again, for that." Now we set to work to clear his hole for "rough Toby" (a long-backed, short-legged, wire-haired terrier of Dandy Dinmont's breed) to enter; in he went like red-hot fire, and "ready to nose the vary deevil himsel sud he meet him," as Jammie Hogg said; and to see the chattering anxiety of the red-coated monkey, as he sat at the mouth of the fox-hole, on his shaggy, grizzle-grey shadow of a horse, like a mounted guardsman in the hole yonder at St. James's; it truly would have made a "pudding creep" with laughter—"Reek, reek, reeking into th' hole after Toby, with his we we cunnin, pinkin, glimmerin een, an' catchin him 'bith stump o' th' tail as he were gooin in an' handing as long as he could," as James said. O, it was a very caricature of a caricature. But list, I hear them scuffle, they are coming out. Notice the monkey shaking his "bit staff;" here they come like a chimney swept in a hurry, they are out. "What a gernin, glowerin, sneerin, deevilitch leuk can a tod gie when hee's keepit at bay just afore he slinks off," exclaimed the poet, as Reynard was stealing away; but yonder they go before the wind, down the sweeping, outstretched glen, like smoke in a blast. Ay, there they go, two stag hounds, monkey, and grew, and Toby yelping behind; what a view we have of them—the grew is too fleet for him, he turns him and keeps him at bay till the hounds come up; now they are off again, and now we lose them, vanished like the shadow of a dream.

We followed, and on our way we met a herdsman, with his eyes staring like two bullets stuck in clay, or rather two currants stuck in a pudding: he said he had met "the deevil, a' dress'd like a heelanman o' tod huntin;" of course we laughed from the bottom end of our very bowels; but that was not the way to undemonize him, no, he pledged himself that he saw him "wi' his own twa een lowp off the shoather o' a thing lik a snagged foal, an' gie the tod such a dirl 'ith heed, that he kilt him deed's a herrin, an' we micht a' witness the same by gannin to the Shouther o' Birkin Brae." And truly it was as he said, for we found the mark of the little Highlandman's shillela on the fox's head, while he himself was sitting a straddle on him, like "the devil looking over Lincoln Minster," and the dogs lying panting round about.

On our road home to Hogg's we paid a visit to a wild-cat's lair in the Eagle's Cragg, and of all the incarnate devils, for fighting I ever saw, they "cow the cuddy," as the Scotch say; perfect fiends on earth. There was pa and ma, or rather dad and mam, (about the bigness of tiger-cats, one was four feet and a half from tip to tail) and seven kittens well grown; and O, the spit, snarl, tusshush and crissish, and mow-waaugh they did kick up in their den, whilst in its darkness we could see the electricity or phosphorescence of their eyes and hair sparkling like chemical fire-works. But I must tell you the rest hereafter, for my paper is out!

W.HFINE ARTS

MR. HAYDON'S PICTURES

Mr. Haydon has nearly completed his Xenophon, which he intends to make the nucleus of an Exhibition during the present town season. The King has graciously lent Mr. Haydon the Mock Election picture; (for an Engraving of which see Mirror, vol. xi. p. 193,) for the above purpose. There will be other pictures, of comic and domestic interest by the same artist; among which will be Waiting for the Times, (purchased by the Marquess of Stafford;) The First Child, very like papa about the eyes, and mamma about the nose; Reading the Scriptures; Falstaff and Pistol; Achilles playing the Lyre; and others, which with a variety of studies, will make up an interesting Exhibition.

THE NATURALIST

A DAY IN BRAZIL

The following is a translation of the leaf from the journal of Dr. Martins, dated Para, August 16, 1819; and describes an equatorial day, as observed near the mouths of the Para and the Amazons:—

How happy am I here! How thoroughly do I now understand many things which before were incomprehensible to me! The glorious features of this wonderful region, where all the powers of nature are harmoniously combined, beget new sensations and ideas. I now feel that I better know what it is to be a historian of nature. Overpowered by the contemplation of an immense solitude, of a profound and inexpressible stillness, it is, doubtless, impossible at once to perceive all its divine characteristics; but the feeling of its vastness and grandeur cannot fail to arouse in the mind of the beholder the thrilling emotions of a hitherto inexperienced delight.

It is three o'clock in the morning, I quit my hammock; for the excitement of my spirits banishes sleep. I open my window, and gaze on the silent solemnity of night. The stars shine with their accustomed lustre, and the moon's departing beam is reflected by the clear surface of the river. How still and mysterious is every thing around me! I take my dark lantern, and enter the cool verandah, to hold converse with my trusty friends the trees and shrubs nearest to our dwelling. Most of them are asleep, with their leaves closely pressed together; others, however, which repose by day, stand erect, and expand themselves in the stillness of night. But few flowers are open; only those of the sweet-scented Paullinia greet me with a balmy fragrance, and thine, lofty mango, the dark shade of whose leafy crown shields me from the dews of night. Moths flit, ghost-like, round the seductive light of my lantern. The meadows, ever breathing freshness, are now saturated with dew, and I feel the damp of the night air on my heated limbs. A Cicàda, a fellow-lodger in the house, attracts me by its domestic chirp back into my bedroom, and is there my social companion, while, in a happy dreaming state, I await the coming day, kept half awake by the buzz of the mosquites, the kettle-drum croak of the bull-frog, or the complaining cry of the goatsucker.

About five o'clock I again look out, and behold the morning twilight. A beautiful even tone of grey, finely blended with a warmth-giving red, now overspreads the sky. The zenith only still remains dark. The trees, the forms of which become gradually distinct, are gently agitated by the land wind, which blows from the east. The red morning light and its reflexes play over the dome-topped caryocars, bertholetias, and symphonias. The branches and foliage are in motion, and all the lately slumbering dreamers are now awake, and bathe in the refreshing air of the morning. Beetles fly, gnats buzz, and the varied voice of the feathered race resounds from every bush; the apes scream as they clamber into the thickets; the night moths, surprised by the approach of light, swarm back in giddy confusion to the dark recesses of the forest; there is life and motion in every path; the rats and all the gnawing tribe are hastily retiring to their holes, and the cunning marten, disappointed of his prey, steals from the farm-yard, leaving untouched the poultry, to whom the watchful cock has just proclaimed the return of day.

The growing light gradually completes the dawn, and at length the effulgent day breaks forth. It is nature's jubilee. The earth awaits her bridegroom, and, behold, he comes! Rays of red light illumine the sky, and now the sun rises. In another moment he is above the horizon, and, emerging from a sea of fire, he casts his glowing rays upon the earth. The magical twilight is gone; bright gleams flit from point to point, accompanied by deeper and deeper shadows. Suddenly the enraptured observer beholds around him the joyous earth, arrayed in fresh dewy splendour, the fairest of brides. The vault of heaven is cloudless; on the earth all is instinct with life, and every animal and plant is in the full enjoyment of existence. At seven o'clock the dew begins to disappear, the land breeze falls off, and the increasing heat soon makes itself sensibly felt. The sun ascends rapidly and vertically the transparent blue sky, from which every vapour seems to disappear; but presently, low in the western horizon, small, flaky, white clouds are formed. These point towards the sun, and gradually extend far into the firmament. By nine o'clock the meadow is quite dry, the forest appears in all the splendour of its glowing foliage. Some buds are expanding; others, which had effloresced more rapidly, have already disappeared. Another hour, and the clouds are higher: they form broad, dense masses, and, passing under the sun, whose fervid and brilliant rays now pervade the whole landscape, occasionally darken and cool the atmosphere. The plants shrink beneath the scorching rays, and resign themselves to the powerful influence of the ruler of the day. The merry buzz of the gold-winged beetle and humming-bird becomes more audible. The variegated butterflies and dragon-flies on the bank of the river, produce, by their gyratory movements, lively and fantastic plays of colour. The ground is covered with swarms of ants, dragging along leaves for their architecture. Even the most sluggish animals are roused by the stimulating power of the sun. The alligator leaves his muddy bed, and encamps upon the hot sand; the turtle and lizard are enticed from their damp and shady retreats; and serpents of every colour crawl along the warm and sunny footpaths.