полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 19, March 9, 1850

Corinna.—Chaucer says somewhere, "I follow Statius first, and then Corinna." Was Corinna in mistake put for Colonna? The

"Guido eke the Colempnis,"whom Chaucer numbers with "great Omer" and others as bearing up the fame of Troy (House of Fame, b. iii.).

Friday Weather.—The following meteorological proverb is frequently repeated in Devonshire, to denote the variability of the weather on Friday:

"Fridays in the weekare never aleek.""Aleek" for "alike," a common Devonianism. Thus Peter Pindar describes a turbulent crowd of people as being

"Leek bullocks sting'd by apple-drones."Is this bit of weather-wisdom current in other parts of the kingdom? I am induced to ask the question, because Chaucer seems to have embodied the proverb in some well-known lines, viz.:—

"Right as the Friday, sothly for to tell,Now shineth it, and now it raineth fast,Right so can gery Venus overcastThe hertes of hire folk, right as hire dayIs gerfull, right so changeth she aray.Selde is the Friday all the weke ylike." The Knighte's Tale, line 1536.Tyndale.—Can any of your readers inform me whether the translation of the "Enchiridion Militis Christiani Erasmi," which Tyndale completed in 1522, was ever printed?

J.M.B.Totnes, Feb. 21. 1850.

LETTER ATTRIBUTED TO SIR ROBERT WALPOLE

In Banks's Dormant Peerage, vol. iii. p. 61., under the account of Pulteney, Earl of Bath, is the following extraordinary letter, said to be from Sir Robert Walpole to King George II., which is introduced as serving to show the discernment of Walpole, as well as the disposition of the persons by whom he was opposed, but evidently to expose the vanity and weakness of Mr. Pulteney, by exhibiting the scheme which was to entrap him into the acceptance of a peerage, and so destroy his popularity. It is dated Jan. 24. 1741, but from no place, and has but little appearance of authenticity.

"Most sacred,

"The violence of the fit of the stone, which has tormented me for some days, is now so far abated, that, although it will not permit me to have the honour to wait on your majesty, yet is kind enough to enable me so far to obey your orders, as to write my sentiments concerning that troublesome man, Mr. Pulteney; and to point out (what I conceive to be) the most effectual method to make him perfectly quiet. Your majesty well knows how by the dint of his eloquence he has so captivated the mob, and attained an unbounded popularity, that the most manifest wrong appears to be right, when adopted and urged by him. Hence it is, that he has become not only troublesome but dangerous. The inconsiderate multitude think that he has not one object but public good in view; although, if they would reflect a little, they would soon perceive that spleen against those your majesty has honoured with your confidence has greater weight with him than patriotism. Since, let any measure be proposed, however salutary, if he thinks it comes from me, it is sufficient for him to oppose it. Thus, sir, you see the affairs of the most momentous concern are subject to the caprice of that popular man; and he has nothing to do but call it a ministerial project, and bellow out the word favourite, to have an hundred pens drawn against it, and a thousand mouths open to contradict it. Under these circumstances, he bears up against the ministry (and, let me add, against your majesty itself); and every useful scheme must be either abandoned, or if it is carried in either house, the public are made to believe it is done by a corrupted majority. Since these things are thus circumstanced, it is become necessary for the public tranquility that he should be made quiet; and the only method to do that effectually is to destroy his popularity, and ruin the good belief the people have in him.

"In order to do this, he must be invited to court; your majesty must condescend to speak to him in the most favourable and distinguished manner; you must make him believe that he is the only person upon whose opinion you can rely, and to whom your people look up for useful measures. As he has already several times refused to take the lead in the administration, unless it was totally modelled to his fancy, your majesty should close in with his advice, and give him leave to arrange the administration as he pleases, and put whom he chooses into office (there can be no danger in that as you can dismiss him when you think fit); and when he has got thus far (to which his extreme self-love and the high opinion he entertains of his own importance, will easily conduce), it will be necessary that your majesty should seem to have a great regard for his health; signifying to him that your affairs will be ruined if he should die; that you want to have him constantly near you, to have his sage advice; and that therefore, as he is much disordered in body, and something infirm, it will be necessary for his preservation for him to quit the House of Commons, where malevolent tempers will be continually fretting him, and where, indeed, his presence will be needless, as no step will be taken but according to his advice; and that he will let you give him a distinguishing mark of your approbation, by creating him a peer. This he may be brought to, for, if I know anything of mankind, he has a love of honour and money; and, notwithstanding his great haughtiness and seeming contempt for honour, he may be won if it be done with dexterity. For, as the poet Fenton says, 'Flattery is an oil that softens the thoughtless fool.'

"If your majesty can once bring him to accept of a coronet, all will be over with him; the changing multitude will cease to have any confidence in him; and when you see that, your majesty may turn your back to him, dismiss him from his post, turn out his meddling partizans, and restore things to quiet; the bee will have lost his sting, and become an idle drone whose buzzing nobody heeds.

"Your majesty will pardon me for the freedom with which I have given my sentiments and advice; which I should not have done, had not your majesty commanded it, and had I not been certain that your peace is much disturbed by the contrivance of that turbulent man. I shall only add that I will dispose several whom I know to wish him well to solicit for his establishment in power, that you may seem to yield to their entreaties, and the finesse be less liable to be discovered.

"I hope to have the honour to attend your majesty in a few days; which I will do privately, that my public presence may give him no umbrage.

(Signed) ROBERT WALPOLE

"(Dated) 24. January, 1741."

As it seems incredible that Walpole could have written such a letter; and the editor does not say where it is taken from, or where the original is, I beg to ask any of your readers whether they have ever seen the letter elsewhere, or attributed by any other writer to Walpole? The editor adds, "accordingly, the scheme took place very soon after, and Mr. Pulteney was in 1742 dignified with the titles before mentioned, i.e. Earl of Bath, &c."

G.BISHOPS OF OSSORY

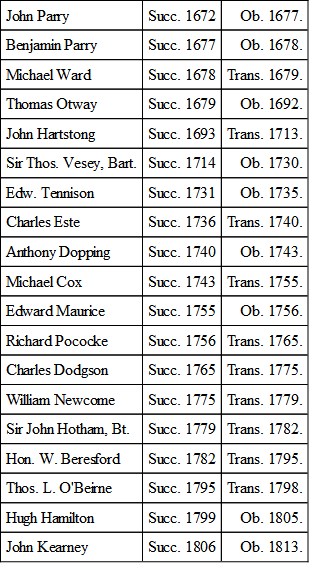

Acting on "R.R.'s" excellent suggestion (No. 16. p. 243. antè), I beg to solicit from all collectors, who may chance to see these lines, information relative to the Bishops of Ossory. I am at present engaged on a work which will comprise that portion of Harris's edition of Sir James Ware's Bishops of Ireland bearing on the see of Ossory. The following names are those concerning whom, especially, information, either original or by reference to rare printed books, will be most thankfully acknowledged:—

I may state, that I have access to that most excellent work Fasti Ecclesiæ Hiberniæ, by Archdeacon Cotton, who has collected many particulars respecting the above-named prelates.

JAMES GRAVES.Kilkenny, Feb. 21. 1850.

Burton's Anatomy of (Religious) Melancholy.—In compliance with the very useful suggestion of "R.R." (No. 16. p. 243.), I venture to express my intention of reprinting the latter part of Burton's "Anatomy of Melancholy," (viz. that relating to Religious Melancholy), and at the same time to intimate my hope that any of your readers who may have it in their power to render me any assistance, will kindly aid me in the work.

M.D.Oxford, Feb. 23.

MINOR QUERIES

Master of Methuen—Ruthven and Gowrie Families.—Colonel Stepney Cowell is desirous of inquiring who was the Master of Methuen, who fell at the Battle of Pinkey, and whose name appears in the battle roll as killed?

Was he married, and did he leave a daughter? He is presumed to have been the son of Lord Methuen by Margaret Tudor, sister of Henry VIII.

Who was the wife of Patrick Ruthven, youngest son of William, first Earl of Gowrie, and where was he married? Any notices of the Gowrie and Ruthven family will be acceptable.

Brooke's Club, St. James's Street, Feb. 18. 1850.

"The Female Captive: a Narrative of Facts which happened in Barbary in the Year 1756. Written by herself." 2 vols. 12 mo. Lond. 1769.—Sir William Musgrave has written this note in the copy which is now in the library of the British Museum:—

"This is a true story. The lady's maiden name was Marsh. She married Mr. Crisp, as related in the narrative; but he, having failed in business, went to India, when she remained with her father, then Agent Victualler, at Chatham, during which she wrote and published these little volumes. On her husband's success in India, she went thither to him.

"The book, having, as it is said, been bought up by the lady's friends, is become very scarce."

Can any of your readers furnish a further account of this lady?

Parliamentary Writs.—It is stated in Duncumb's History of Herefordshire, 1. 154. that "the writs, indentures, and returns, from 17 Edw. IV. to 1 Edw. VI., are all lost throughout England, except one imperfect bundle, 33rd Hen. VIII." This book was published in 1803. Have the researches since that time in the Record Offices supplied this hiatus; and if so, in which department of it are these documents to be found?

W.H.C.Temple.

Portraits in the British Museum.—I have often wished to inquire, but knew not where till your publication met my notice, as to the portraits in the British Museum, which are at present hung so high above beasts and birds, and everything else, that it requires better eyes than most people possess to discern their features. I should suppose that if they were not originals and of value, they would not have been lodged in the Museum, and if they are, why not appropriate a room to them, where they might be seen to advantage, by those who take pleasure in such representations of the celebrated persons of former days? Any information on this subject will be gratefully received.

L.O.REPLIES

COLLEGE SALTING

In reply to the query of the Rev. Dr. Maitland (No. 17. p. 261.), I would remark, that Salting was the ceremony of initiating a freshman into the company of senior students or sophisters. This appears very clearly from a passage in the Life of Anthony a Wood (ed. 1771, pp. 45-50.). Anthony a Wood was matriculated in the University of Oxford, 26th May, 1647, and on the 18th of October "he was entered into the Buttery-Book of Merton College." At various periods, from All Saints till Candlemas, "there were Fires of Charcole made in the Common hall."

"At all these Fires every Night, which began to be made a little after five of the clock, the Senior Under-Graduats would bring into the hall the Juniors or Freshmen between that time and six of the clock, and there make them sit down on a Forme in the middle of the Hall, joyning to the Declaiming Desk: which done, every one in Order was to speake some pretty Apothegme, or make a Jest or Bull, or speake some eloquent Nonsense, to make the Company laugh: But if any of the Freshmen came off dull or not cleverly, some of the forward or pragmatical Seniors would Tuck them, that is, set the nail of their Thumb to their chin, just under the Lipp, and by the help of their other Fingers under the Chin, they would give him a chuck, which sometimes would produce Blood. On Candlemas day, or before (according as Shrove Tuesday fell out), every Freshman had warning given him to provide his Speech, to be spoken in the publick Hall before the Under-Graduats and Servants on Shrove-Tuesday night that followed, being alwaies the time for the observation of that Ceremony. According to the said Summons A. Wood provided a Speech as the other Freshmen did.

"Shrove Tuesday Feb. 15, the Fire being made in the Common hall before 5 of the Clock at night, the Fellowes would go to Supper before six, and making an end sooner than at other times, they left the Hall to the Libertie of the Undergraduats, but with an Admonition from one of the Fellowes (who was the Principall of the Undergraduats and Postmasters) that all things should be carried in good Order. While they were at Supper in the Hall, the Cook (Will. Noble) was making the lesser of the brass pots full of Cawdle at the Freshmens Charge; which, after the Hall was free from the Fellows, was brought up and set before the Fire in the said Hall. Afterwards every Freshman, according to seniority, was to pluck off his Gowne and Band, and if possible to make himself look like a Scoundrell. This done, they were conducted each after the other to the high Table, and there made to stand on a Forme placed thereon; from whence they were to speak their Speech with an audible voice to the Company: which, if well done, the person that spoke it was to have a Cup of Cawdle and no salted Drinke; if indifferently, some Cawdle and some salted Drinke; but if dull, nothing was given to him but salted Drinke or salt put in College Bere, with Tucks to book. Afterwards when they were to be admitted into the Fraternity, the Senior Cook was to administer to them an Oath over an old Shoe, part of which runs thus: Item tu jurabis, quot penniless bench non visitabis, &c.: the rest is forgotten, and none there are that now remembers it. After which spoken with gravity, the Freshman kist the Shoe, put on his Gowne and Band, and took his place among the Seniors."

Mr. Wood gives part of his speech, which is ridiculous enough. It appears that it was so satisfactory that he had cawdle and sack without and salted drink. He concludes thus:—

"This was the way and custome that had been used in the College, time out of mind, to initiate the Freshmen; but between that time and the restoration of K. Ch. 2. it was disused, and now such a thing is absolutely forgotten."

The editors in a note intimate that it was probable the custom was not peculiar to Merton College, and that it was perhaps once general, as striking traces of it might be found in many societies in Oxford, and in some a very near resemblance of it had been kept up until within a few years of that time (1772).

C.H. COOPER.Cambridge, Feb. 23. 1850.

"E.V.," after quoting the passage given by Mr. Cooper from Anthony Wood, proceeds:—

It is clear from Owen's epigram that there was some kind of salting at Oxford as well as at Cambridge; is it not at least probable that they were both identical with the custom described by old Anthony, and that the charge made in the college book was for the cawdle mentioned above, as provided at the freshman's expense; the whole ceremony going under the name of "salting," from the salt and water potion, which was the most important constituent of it? If this be so, it agrees with Dr. Maitland's idea, that "this 'salting' was some entertainment given by the newcomer, from and after which he ceases to be fresh;" or, as Wood expresses it, "he took his place among the seniors."

The "tucks" he speaks of could have been no very agreeable addition to the salted beer; for, as he himself explains it, a few lines above, "to tuck" consisted in "setting the nail of the thumb to their chin, just under the lip, and by the help of their other fingers under the chin, they would give him a mark, which sometimes would produce blood."

Before I leave Anthony Wood, let me mention that I find him making use of the word "bull" in the sense of a laughable speech ("to make a jest, or bull, or speake some eloquent nonsense," p. 34.), and of the now vulgar expression "to go to pot." When recounting the particulars of the parliamentary visitation of the University in 1648, he tells us, that had it not been for the intercession of his mother to Sir Nathan Brent, "he had infallible gone to the pot." If Dr. Maitland or any of your readers can give the history of these expressions, and can produce earlier instances of their use, they would greatly oblige me.

P.S. I ought to mention, that "Penniless Bench" was a seat for loungers, under a wooden canopy, at the east end of old Carfax Church: it seems to have been notorious as "the idle corner" of Oxford.

E.V.QUERIES ANSWERED, NO. 5

A comparative statement of the number of those who ask questions, and those who furnish replies, would be a novel contribution to the statistics of literature. I do note mean to undertake it, but shall so far assume an excess on the side of the former class, as to attempt a triad of replies to recent queries without fear of the censures which attach to monopoly.

To facilitate reference to the queries, I take them in the order of publication:—

1. "What is the earliest known instance of the use of a beaver hat in England?"—T. Hudson Turner, p. 100.

The following instance from Chaucer (Canterbury tales, 1775, 8°. v. 272.), if not the earliest, is precise and instructive:

"A marchant was ther with a forked berd,In mottelee, and highe on hors he sat,And on his hed a Flaundrish bever hat."2. "Has Cosmopoli been ever appropriated to any known locality?"—John Jebb, p. 213.

Cosmopolis has been used for London, and for Paris (G. Peignot, Répertoire de bibliographies spéciales, Paris, 1810. 8°. pp. 116, 132.) It may also, in accordance with its etymology, be used for Amsterdam, or Berlin, or Calcutta, etc. As an imprint, it takes the dative case. The Interpretationes paradoxæ quatuor evangeliorum of Sandius, were printed at Amsterdam. (M. Weiss, Biographie universelle, Paris, 1811 28. 8°. xl. 312.)

3. References to "any works or treatises supplying information on the history of the Arabic numerals" are requested by "E.N." p. 230.

To the well chosen works enumberated by the querist, I shall add the titles of two valuable publications in my own collection:

DICTIONNAIRE RAISONNÉ DE DIPLOMATIQUE—par dom de Vaines. Paris, 1774. 8°. 2 vol.

ELÉMENTS DE PALÉOGRAPHIE, par M. Natalis de Wailly. Paris, Imprimerie royale, 1838. 4°. 2 vol.

The former work is a convenient epitome of the Nouveau traité de diplomatique. The latter is a new compilation, undertaken with the sanction of M. Guizot. Its appearance was thus hailed by the learned Daunou: "Cet ouvrage nous semble recommandable par l'exactitude des recherches, par la distribution méthodique des matières et par l'élégante précision du style." (Journal des savants, Paris, 1838. 4°. p. 328.)

A query should always be worded with care, and put in a quotable shape. The observance of this plain rule would economise space, save the time which might otherwise be occupied in useless research, and tend to produce more pertinency of reply. The first and second of the above queries may serve as models.

Bolton Corney.REPLIES TO MINOR QUERIES

Old Auster Tenement (No. 14. p. 217.).—I think that I am in a condition to throw some light on the meaning of this expression, noticed in a former Number by "W.P.P." The tenements held in villenage of the lord of a manor, at least where they consisted of a messuage or dwelling-house, are often called astra in our older books and court-rolls. If the tenement was an ancient one, it was vetus or antiquum astrum; if a tenure of recent creation (or a new-take, as it is called in some manors), it was novum astrum. The villenage tenant of it was an astrarius. "W.P.P." may satisfy himself of these facts by referring to the printed Plautorum Abbrevietis, fo. 282.; to Fleta, Comment. Juris. Anglicani, ed. 1685, p. 217.; and to Ducange, Spelman, and Cowel, under the words "Astrum," "Astrarius," and "Astre." In the very locality to which "W.P.P." refers, he will find that the word "Auster" is "Astrum" in the oldest court-rolls, and that the term is not confined to North Curry, but is very prevalent in the eastern half of Somerset. At the present day, an auster tenement is a species of copyhold, with all the incidents to that tenure. It is noticed in the Journal of the Archæological Institute, in a recent critique on Dr. Evans's Leicestershire words, and is very familar to legal practitioners of any experience in the district alluded to.

E. Smirke.Tureen (No. 16. p. 246.).—There is properly no such word. It is a corruption of the French terrine, an earthen vessel in which soup is served. It is in Bailey's Dictionary. I take this opportunity of suggesting whether that the word "swinging," applied by Goldsmith to his tureen, should be rather spelt swingeing; though the former is the more usual way: a swinging dish and a swingeing are different things, and Goldsmith meant the latter.

C.Burning the Dead.—"T." will find some information on this subject in Sir Thomas Browne's Hydriotaphia, chap. i., which appears to favour his view except in the following extract:

"The same practice extended also far west, and besides Heruleans, Getes and Thracians, was in use with most of the Celtæ, Sarmatians, Germans, Gauls, Danes, Swedes, Norwegians; not to omit some use thereof among Carthaginians, and Americans."

The Carthaginians most probably received the custom from their ancestors the Phoenicians, but where did the Americans get it?

Henry St. Chad.Corpus Christi Hall, Maidstone, Feb. 8. 1850.

Burning the Dead.—Your correspondent "T." (No. 14. p. 216.) can hardly have overlooked the case of Dido, in his inquiry "whether the practice of burning the dead has ever been in vogue amongst any people, excepting the inhabitants of Europe and Asia?" According to all classical authorities, Dido was founder and queen of Carthage in Africa, and was burned at Carthage on a funeral pile.

If it be said that Dido's corpse underwent burning in conformity with the custom of her native country Tyre, and not because it obtained in the land of her adoption, then the question arises, whether burning the dead was not one of the customs which the Tyrian colony of Dido imported into Africa, and became permanently established at Carthage. It is very certain that the Carthaginians had human sacrifices by fire, and that they burned their children in the furnace to Saturn.

A.G.Ecclesfield, Feb. 8. 1850.

MISCELLANIES

M. de Gournay.—The author of the axioms Laissez faire, laissez passer, which are the sum and substance of the free trade principles of political economy, and perhaps the pithiest and completest exposition of the doctrine of a particular school ever made, was Jean Claude Marie Vincent de Gournay, who was born at St. Malo in 1712, and died at Paris in 1759. In early life he was engaged in trade, and subsequently became Honorary Councillor of the Grand Council, and Honorary Intendant of Commerce. He translated, in 1742, Josiah Child's Considerations on Commerce and on the Interest on Money, and Culpepper's treatise Against Usury. He also wrote a good deal on questions of political economy. He was, in fact, with Dr. Quesnay, the chief of the French economists of the last century; but he was more liberal than Quesnay in his doctrines; indeed he is (far more than Adam Smith) the virtual founder of the modern school of political economy; and yet, perhaps, of all the economists he is the least known!