полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 51, January, 1862

It is deeply to be lamented that so many naturalists have entirely overlooked this significant advice of Cuvier’s, to combine zoölogical and anatomical studies in order to arrive at a clearer perception of the true affinities among animals. To sum it up in one word, he tells us that the secret of his method is “comparison,”—ever comparing and comparing throughout the enormous range of his knowledge of the organization of animals, and founding upon the differences as well as the similarities those broad generalizations under which he has included all animal structures. And this method, so prolific in his hands, has also a lesson for us all. In this country there is a growing interest in the study of Nature; but while there exist hundreds of elementary works illustrating the native animals of Europe, there are few such books here to satisfy the demand for information respecting the animals of our land and water. We are thus forced to turn more and more to our own investigations and less to authority; and the true method of obtaining independent knowledge is this very method of Cuvier’s,—comparison.

Let us make the most common application of it to natural objects. Suppose we see together a Dog, a Cat, a Bear, a Horse, a Cow, and a Deer. The first feature that strikes us as common to any two of them is the horn in the Cow and Deer. But how shall we associate either of the others with these? We examine the teeth, and find those of the Dog, the Cat, and the Bear sharp and cutting, while those of the Cow, the Deer, and the Horse have flat surfaces, adapted to grinding and chewing, rather than cutting and tearing. We compare these features of their structure with the habits of these animals, and find that the first are carnivorous, that they seize and tear their prey, while the others are herbivorous or grazing animals, living only on vegetable substances, which they chew and grind. We compare farther the Horse and Cow, and find that the Horse has front teeth both in the upper and lower jaw, while the Cow has them only in the lower; and going still farther and comparing the internal with the external features, we find this arrangement of the teeth in direct relation to the different structure of the stomach in the two animals,—the Cow having a stomach with four pouches, adapted to a mode of digestion by which the food is prepared for the second mastication, while the Horse has a simple stomach. Comparing the Cow and the Deer, we find that the digestive apparatus is the same in both; but though they both have horns, in the Cow the horn is hollow, and remains through life firmly attached to the bone, while in the Deer it is solid and is shed every year. With these facts before us, we cannot hesitate to place the Dog, the Cat, and the Bear in one division, as carnivorous animals, and the other three in another division as herbivorous animals,—and looking a little farther, we perceive, that, in common with the Cow and the Deer, the Goat and the Sheep have cloven feet, and that they are all ruminants, while the Horse has a single hoof, does not ruminate, and must therefore be separated from them, even though, like them, he is herbivorous.

This is but the simplest illustration, taken from the most familiar objects, of this comparative method; but the same process is equally applicable to the most intricate problems in animal structures, and will give us the clue to all true affinities between animals. The education of a naturalist, now, consists chiefly in learning how to compare. If he have any power of generalization, when he has collected his facts, this habit of mental comparison will lead him up to principles, to the great laws of combination. It must not discourage us, that the process is a slow and laborious one, and the results of one lifetime after all very small. It might seem invidious, were I to show here how small is the sum total of the work accomplished even by the great exceptional men, whose names are known throughout the civilized world. But I may at least be permitted to speak of my own efforts, and to sum up in the fewest words the result of my life’s work. I have devoted my whole life to the study of Nature, and yet a single sentence may express all that I have done. I have shown that there is a correspondence between the succession of Fishes in geological times and the different stages of their growth in the egg,—this is all. It chanced to be a result that was found to apply to other groups and has led to other conclusions of a like nature. But, such as it is, it has been reached by this system of comparison, which, though I speak of it now in its application to the study of Natural History, is equally important in every other branch of knowledge. By the same process the most mature results of scientific research in Philology, in Ethnology, and in Physical Science are reached. And let me say that the community should foster the purely intellectual efforts of scientific men as carefully as they do their elementary schools and their practical institutions, generally considered so much more useful and important to the public. For from what other source shall we derive the higher results that are gradually woven into the practical resources of our life, except from the researches of those very men who study science not for its uses, but for its truth? It is this that gives it its noblest interest: it must be for truth’s sake, and not even for the sake of its usefulness to humanity, that the scientific man studies Nature. The application of science to the useful arts requires other abilities, other qualities, other tools than his; and therefore I say that the man of science who follows his studies into their practical application is false to his calling. The practical man stands ever ready to take up the work where the scientific man leaves it, and to adapt it to the material wants and uses of daily life.

The publication of Cuvier’s proposition, that the animal kingdom is built on four plans, created an extraordinary excitement throughout the scientific world. All naturalists proceeded to test it, and many soon recognized in it a great scientific truth,—while others, who thought more of making themselves prominent than of advancing science, proposed poor amendments, that were sure to be rejected on farther investigation. There were, however, some of these criticisms and additions that were truly improvements, and touched upon points overlooked by Cuvier. Blainville, especially, took up the element of form among animals,—whether divided on two sides, whether radiated, whether irregular, etc. He, however, made the mistake of giving very elaborate names to animals already known under simpler ones. Why, for instance, call all animals with parts radiating in every direction Actinomorpha or Actinozoaria, when they had received the significant name of Radiates? It seemed, to be a new system, when in fact it was only a new name. Ehrenberg, likewise, made an important distinction, when he united the animals according to the difference in their nervous systems; but he also incumbered the nomenclature unnecessarily, when he added to the names Anaima and Enaima of Aristotle those of Myeloneura and Ganglioneura.

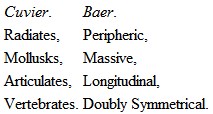

But it is not my object to give all the classifications of different authors here, and I will therefore pass over many noted ones, as those of Burmeister, Milne, Edwards, Siebold and Stannius, Owen, Leuckart, Vogt, Van Beneden, and others, and proceed to give some account of one investigator who did as much for the progress of Zoölogy as Cuvier, though he is comparatively little known among us. Karl Ernst von Baer proposed a classification based, like Cuvier’s, upon plan; but he recognized what Cuvier failed to perceive,—namely, the importance of distinguishing between type (by which he means exactly what Cuvier means by plan) and complication of structure,—in other words, between plan and the execution of the plan. He recognized four types, which correspond exactly to Cuvier’s four plans, though he calls them by different names. Let us compare them.

Though perhaps less felicitous, the names of Baer express the same ideas as those of Cuvier. By the Peripheric he signified those in which all the parts converge from the periphery or circumference of the animal to its centre. Cuvier only reverses this definition in his name of Radiates, signifying the animals in which all parts radiate from the centre to the circumference. By Massive, Baer indicated those animals in which the structure is soft and concentrated, without a very distinct individualization of parts,—exactly the animals included by Cuvier under his name of Mollusks, or soft-bodied animals. In his selection of the epithet Longitudinal, Baer was less fortunate; for all animals have a longitudinal diameter, and this word was not, therefore, sufficiently special. Yet his Longitudinal type answers exactly to Cuvier’s Articulates,—animals in which all parts are arranged in a succession of articulated joints along a longitudinal axis. Cuvier has expressed this jointed structure in the name Articulates; whereas Baer, in his name of Longitudinal, referred only to the arrangement of joints in longitudinal succession, in a continuous string, as it were, one after another. For the Doubly Symmetrical type his name is the better of the two; for Cuvier’s name of Vertebrates alludes only to the backbone,—while Baer, who is an embryologist, signifies in his their mode of growth also. He knew what Cuvier did not know, that in its first formation the germ of the Vertebrate divides in two folds: one turning up above the backbone, to inclose all the sensitive Organs,—the spinal marrow, the organs of sense, all those organs by which life is expressed; the other turning down below the backbone, and inclosing all those organs by which life is maintained,—the organs of digestion, of respiration, of circulation, of reproduction, etc. So there is in this type not only an equal division of parts on either side, but also a division above and below, making thus a double symmetry in the plan, expressed by Baer in the name he gave it. Baer was perfectly original in his conception of these four types, for his paper was published in the very same year with that of Cuvier. But even in Germany, his native land, his ideas were not fully appreciated: strange that it should be so,—for, had his countrymen recognized his genius, they might have claimed him as the compeer of the great French naturalist.

Baer also founded the science of Embryology, under the guidance of his teacher, Dollinger. His researches in this direction showed him that animals were not only built on four plans, but that they grew according to four modes of development. The Vertebrate arises from the egg differently from the Articulate,—the Articulate differently from the Mollusk,—the Mollusk differently from the Radiate. Cuvier only showed us the four plans as they exist in the adult; Baer went a step farther, and showed us the four plans in the process of formation. But his greatest scientific achievement is perhaps the discovery that all animals originate in eggs, and that all these eggs are at first identical in substance and structure. The wonderful and untiring research condensed into this simple statement, that all animals arise from eggs and that all those eggs are identical in the beginning, may well excite our admiration. This egg consists of an outer envelope, the vitelline membrane, containing a fluid more or less dense, the yolk; within this is a second envelope, the so-called germinative vesicle, containing a somewhat different and more transparent fluid, and in the fluid of this second envelope float one or more so-called germinative specks. At this stage of their growth all eggs are microsopically small, yet each one has such tenacity of its individual principle of life that no egg was ever known to swerve from the pattern of the parent animal that gave it birth.

III

From the time that Linnæus showed us the necessity of a scientific system as a framework for the arrangement of scientific facts in Natural History, the number of divisions adopted by zoölogists and botanists increased steadily. Not only were families, orders, and classes added to genera and species, but these were further multiplied by subdivisions of the different groups. But as the number of divisions increased, they lost in precise meaning, and it became more and more doubtful how far they were true to Nature. Moreover, these divisions were not taken in the same sense by all naturalists: what were called families by some were called orders by others, while the orders of some were the classes of others, till it began to be doubted whether these scientific systems had any foundation in Nature, or signified anything more than that it had pleased Linnæus, for instance, to call certain groups of animals by one name, while Cuvier had chosen to call them by another.

These divisions are, first, the most comprehensive groups, the primary divisions, called branches by some, types by others, and divided by some naturalists into so-called sub-types, meaning only a more limited circumscription of the same kind of group; next we have classes, and these also have been divided into sub-classes, then orders and sub-orders, families, sub-families, and tribes; then genera, species, and varieties. With reference to the question, whether these groups really exist in Nature or are merely the expression of individual theories and opinions, it is worth while to study the works of the early naturalists, in order to trace the natural process by which scientific classification has been reached; for in this, as in other departments of learning, practice has always preceded theory. We do the thing before we understand why we do it: speech precedes grammar, reason precedes logic; and so a division of animals into groups, upon an instinctive perception of their differences, has preceded all our scientific creeds and doctrines. Let us, therefore, proceed to examine the meaning of these names as adopted by naturalists.

When Cuvier proposed his four primary divisions of the animal kingdom, he added his argument for their adoption,—because, he said, they are constructed on four different plans. All the progress in our science since his time confirms this result; and I shall attempt to show that there are really four, and only four, such structural ideas at the foundation of the animal kingdom, and that all animals are included under one or another of them. But it does not follow, that, because we have arrived at a sound principle, we are therefore unerring in our practice. From ignorance we may misplace animals, and include them under the wrong division. This is a mistake, however, which a better insight into their organization rectifies; and experience constantly proves, that, whenever the structure of an animal is perfectly understood, there is no hesitation as to the head under which it belongs. We may consequently test the merits of these four primary groups on the evidence furnished by investigation. It has already been seen that these plans may be presented in the most abstract manner without any reference to special animals. Radiation expresses in one word the idea on which the lowest of these types is based. In Radiates we have no prominent bilateral symmetry, as in all other animals, but an all-sided symmetry, in which there is no right and left, no anterior and posterior extremity, no above and below. They are spheroidal bodies; yet, though many of them remind us of a sphere, they are by no means to be compared to a mathematical sphere, but rather to an organic sphere, so loaded with life, as it were, as to produce an infinite variety of radiate symmetry. The whole organization is arranged around a centre toward which all the parts converge, or, in a reverse sense, from which all the parts radiate. In Mollusks there is a longitudinal axis and a bilateral symmetry; but the longitudinal axis in these soft concentrated bodies is not very prominent; and though the two ends of this axis are distinct from each other, the difference is not so marked that we can say at once, for all of them, which is the anterior and which the posterior extremity. In this type, right and left have the preponderance over the other diameters of the body. The sides are the prominent parts,—they are charged with the important organs, loaded with those peculiarities of the structure that give it character. The Oyster is a good instance of this, with its double valve, so swollen on one side, so flat on the other. There is an unconscious recognition of this in the arrangement of all collections of Mollusks; for, though the collectors do not put up their specimens with any intention of illustrating this peculiarity, they instinctively give them the position best calculated to display their distinctive characteristics, and to accomplish this they necessarily place them in such a manner as to show the sides. In Articulates there is also a longitudinal axis of the body and a bilateral symmetry in the arrangement of parts; the head and tail are marked, and the right and left sides are distinct. But the prominent tendency in this type is the development of the dorsal and ventral region; here above and below prevail over right and left. It is the back and the lower side that have the preponderance over any other part of the structure in Articulates. The body is divided from end to end by a succession of transverse constrictions, forming movable rings; but the character of the animal, its striking features, are always above or below, and especially developed on the back. Any collection of Insects or Crustacea is an evidence of this; being always instinctively arranged in such a manner as to show the predominant features, they uniformly exhibit the back of the animal. The profile view of an Articulate has no significance; whereas in a Mollusk, on the contrary, the profile view is the most illustrative of the structural character. In the highest division, the Vertebrates, so characteristically called by Baer the Doubly Symmetrical type, a solid column runs through the body with an arch above and an arch below, thus forming a double internal cavity. In this type, the head is the prominent feature; it is, as it were, the loaded end of the longitudinal axis, so charged with vitality as to form an intelligent brain, and rising in man to such predominance as to command and control the whole organism. The structure is arranged above and below this axis, the upper cavity containing all the sensitive organs, and the lower cavity containing all those by which life is maintained.

While Cuvier and his followers traced these four distinct plans, as shown in the adult animal, Baer opened to us a new field of investigation in the embryology of the four types, showing that for each there was a special mode of growth in the egg. Looking at them from this point of view, we shall see that these four types, with their four modes of growth, seem to fill out completely the plan or outline of the animal kingdom, and leave no reason to expect any further development or any other plan of animal life within these limits. The eggs of all animals are spheres, such as I have described them; but in the Radiate the whole periphery is transformed into the germ, so that it becomes, by the liquefying of the yolk, a hollow sphere. In the Mollusks, the germ lies above the yolk, absorbing its whole substance through the under side, thus forming a massive close body instead of a hollow one. In the Articulate, the germ is turned in a position exactly opposite to that of the Mollusk, and absorbs the yolk upon the back. In the Vertebrate, the germ divides in two folds, one turning upward, the other turning downward, above and below the central backbone. These four modes of development seem to exhaust the possibilities of the primitive sphere, which is the foundation of all animal life, and therefore I believe that Cuvier and Baer were right in saying that the whole animal kingdom is included under these four structural ideas.

Leuckart proposed to subdivide the Radiates into two groups: the Coelenterata, including Polyps and Acalephs or Jelly-Fishes,—and Echinoderms, including Star-Fishes, Sea-Urchins, and Holothurians. His reason for this distinction is the fact that in the latter the organs are inclosed within walls of their own, distinct from the body-wall; whereas in the former the organs are formed by internal folds of the outer wall of the body, as in the Polyps, or are hollowed out of the substance of the body, as in Jelly-Fishes. This implies no difference in the plan, but merely a difference in the execution of the plan. Both are equally radiate in their structure; and when Leuckart separated them as distinct primary types, he mistook a difference in the material expression of the plan for a difference in the plan itself. So some naturalists have distinguished Worms from the other Articulates as a separate division. But the structural plan of this type is a body divided by transverse constrictions or joints; and whether those joints are uniformly arranged from one end of the body to the other, as in the Worms, or whether the front joints are soldered together so as to form two regions of the body, as in Crustacea, or divided so as to form three regions of the body, as in winged Insects, does not in the least affect the typical character of the structure, which remains the same in all. Branches or types, then, are natural groups of the animal kingdom, founded on plans of structure or structural ideas.

What now are classes? Are they lesser divisions, differing only in extent, or are they founded on special characters? I believe the latter view to be the true one, and that class characters have a significance quite different from that of their mere range or extent. These divisions are founded on certain categories of structure; and were there but one animal of a class in the world, if it had those characters on which a class is founded, it would be as distinct from all other animals as if its kind were counted by thousands. Baer approached the idea of the classes when he discriminated between plan of structure or type and the degree of perfection in the structure. But while he understands the distinction between a plan and its execution, his ideas respecting the different features of structure are not quite so precise. He does not, for instance, distinguish between the complication of a given structure and the mode of execution of a plan, both of which are combined in what he calls degrees of perfection. And yet, without this distinction, the difference between classes and orders cannot be understood; for classes and orders rest upon a just appreciation of these two categories, which are quite distinct from each other, and have by no means the same significance. Again, quite distinct from both of these is the character of form, not to be confounded either with complication of structure, on which orders are based, or with the execution of the plan, on which classes rest. An example will show that form is no guide for the determination of classes or orders. Take, for instance, a Beche-de-Mer, a member of the highest class of Radiates, and compare it with a Worm. They are both long cylindrical bodies; but one has parallel divisions along the length of the body, the other has the body divided by transverse rings. Though in external form they resemble each other, the one is a worm-like Radiate, the other is a worm-like Articulate, each having the structure of its own type; so that they do not even belong to the same great division of the animal kingdom, much less to the same class. We have a similar instance in the Whales and Fishes,—the Whales having been for a long time considered as Fishes, on account of their form, while their structural complication shows them to be a low order of the class of Mammalia, to which we ourselves belong, that class being founded upon a particular mode of execution of the plan characteristic of the Vertebrates, while the order to which the Whales belong depends upon their complication of structure, as compared with other members of the same class. We may therefore say that neither form nor complication of structure distinguishes classes, but simply the mode of execution of a plan. In Vertebrates, for instance, how do we distinguish the class of Mammalia from the other classes of the type? By the peculiar development of the brain, by their breathing through lungs, by their double circulation, by their bringing forth living young and nursing them with milk. In this class the beasts of prey form a distinct order, superior to the Whales or the herbivorous animals, on account of the higher complication of their structure; and for the same reason we place the Monkeys above them all. But among the beasts of prey we distinguish the Bears, as a family, from the family of Dogs, Wolves, and Cats, on account of their different form, which does not imply a difference either in the complication of their structure or in the mode of execution of their plan.