полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 477, February 19, 1831

BURNS

This extraordinary man, before he produced any of the pieces on which his fame is built, had educated himself abundantly; and when he died, at the age of thirty-seven, knew more of books, as well as of men, than fifty out of a hundred in any of the learned professions in any country of the world are ever likely to do.—Ibid.

THE ETTRICK SHEPHERD

When the Ettrick Shepherd was first heard of, he had indeed but just learned to write, by copying the letters of a printed ballad, as he lay watching his flock on the mountains; but thirty years or more have passed since then, and his acquirements are now such, that the Royal Society of Literature, in patronizing him, might be justly said to honour a laborious and successful student, as well as a masculine and fertile genius. We may take the liberty of adding, in this place, what perhaps may not be known to the excellent managers of that excellent institution, that a more worthy, modest, sober, and loyal man does not exist in his majesty's dominions than this distinguished poet, whom some of his waggish friends have taken up the absurd fancy of exhibiting in print as a sort of boozing buffoon; and who is now, instead of revelling in the license of tavern-suppers and party politics, bearing up, as he may, against severe and unmerited misfortunes, in as dreary a solitude as ever nursed the melancholy of a poetical temperament.—Ibid.

MR. ALLAN CUNNINGHAM

Needs no testimony either to his intellectual accomplishments or his moral worth; nor, thanks to his own virtuous diligence, does he need any patronage. He has been fortunate enough to secure a respectable establishment in the studio of a great artist, who is not less good than great, and would thus be sufficiently in the eye of the world, even were his literary talents less industriously exercised than they have hitherto been. His recent Lives of the British Painters and Sculptors form one of the most agreeable books in the language; and it will always remain one of the most remarkable and delightful facts in the history of letters, that such a work—one conveying so much valuable knowledge in a style so unaffectedly attractive—so imbued throughout, not only with lively sensibility, amiable feelings, honesty and candour, but mature and liberal taste, was produced by a man who, some twenty years before, earned his daily bread as a common stone-mason in the wilds of Nithsdale. Examples like these will plead the cause of struggling genius, wherever it may be found, more powerfully than all the arguments in the world.—Ibid.

DUELLING

Is the only crime into which an upright man, wanting in moral firmness, can be impelled by the law of honour. Surely there could be no difficulty in putting an end to this absurd and abominable practice by wholesome laws. Appoint six months' imprisonment for the offence of sending a challenge, or of accepting it; two years if the parties meet; and if one falls, transport the other for life. Appoint the same punishment in all cases for the seconds; and from the day in which such a law should be enacted, not a pair of duelling pistols would ever again be manufactured in this country, even for the Dublin market.—Ibid.

CARDINAL MAZARIN

The pecuniary wealth, the valuables and pictures of Mazarin, were immense. He was fond of hoarding,—a passion that seized him when he first found himself banished and destitute. His love of pictures was as strong as his love of power—stronger, since it survived. A fatal malady had seized on the cardinal, whilst engaged in the conferences of the treaty, and worn by mental fatigue. He brought it home with him to the Louvre. He consulted Guenaud, the great physician, who told him that he had two months to live. Some days after receiving this dread mandate, Brienne perceived the cardinal in night-cap and dressing gown tottering along his gallery, pointing to his pictures, and exclaiming, "Must I quit all these?" He saw Brienne, and seized him: "Look," exclaimed he, "look at that Correggio! this Venus of Titian! that incomparable Deluge of Caracci! Ah! my friend, I must quit all these. Farewell, dear pictures, that I loved so dearly, and that cost me so much!" His friend surprised him slumbering in his chair at another time, and murmuring, "Gueriaud has said it! Guenaud has said it!" A few days before his death, he caused himself to be dressed, shaved, rouged and painted, "so that he never looked so fresh and vermilion," in his life. In this state he was carried in his chair to the promenade, where the envious courtiers cruelly rallied, and paid him ironical compliments on his appearance. Cards were the amusement of his death-bed, his hand being held by others; and they were only interrupted by the visit of the Papal Nuncio, who came to give the cardinal that plenary indulgence to which the prelates of the sacred college are officially entitled. Mazarin expired on the 9th of March, 1661.

Lardner's Cyclopaedia, vol. xv."GOD SAVE THE KING" IN ITALY

On the 26th of December last, the King and Queen of Sardinia went in state to the Carlo Felice Theatre at Genoa, and presented to the public, says an Italian correspondent, his niece, the betrothed bride of the heir-apparent of the house of Austria. At seven the court arrived, the curtain rose, and displayed the whole corps dramatique, who sang Dio Salve il Re; or an Italian version of the words and music of our "God save the King," in which Madame Caradori took the principal part. Thus our national anthem is getting naturalized in Italy, the parent of song, and once the manufacturer of it for all Europe. It is already adopted in Russia, I am told, and is well known in France, though not likely to supplant the fine national air, "Vive Henri Quatre."—Harmonicon, Feb. 1.

ILLUSTRATIONS OF SHAKSPEARE

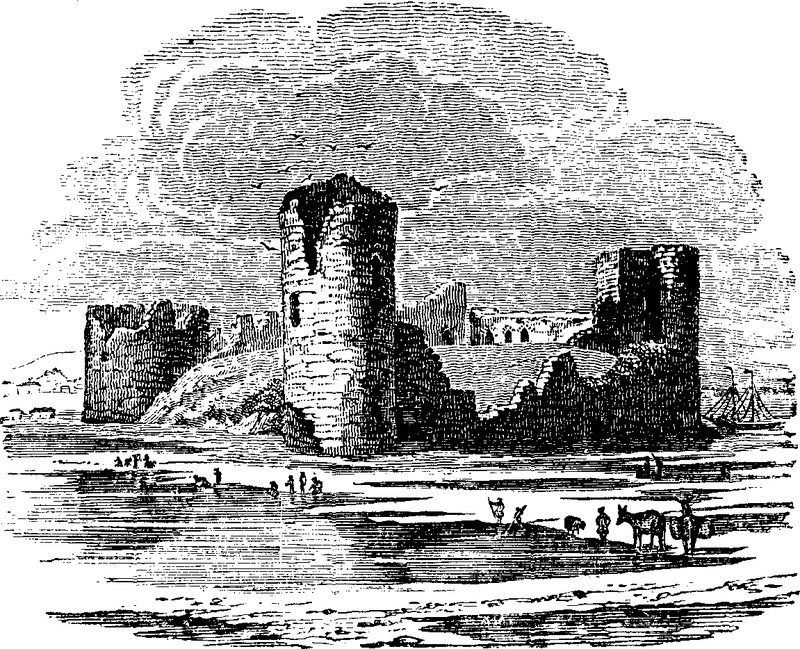

FLINT CASTLE.

This Castle is, or rather was, situated on an insulated rock, in a marsh on the river Dee, which still, at high tides, washes its walls. It is a site of considerable historical interest, being the place where the unhappy King Richard II was delivered into the hands of his rival, Bolingbroke. The unfortunate monarch, it appears, finding himself deserted, had withdrawn to North Wales, with a design to escape to France. He was, however, decoyed to agree to a conference with Bolingbroke, and on the road was seized by an armed force, conveyed to Flint Castle, and thence led by his successful rival to the metropolis.

Shakspeare has perpetuated Flint Castle by its frequent mention in his "Life and Death of King Richard the Second." He has indeed invested it with high poetical interest. Thus, in Scene 2 of Act iii. where occurs that touching lament of unkingship—

——Of comfort, no man speak:Let's talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs, &c.Again, where the moody monarch says—

——What comfort have we now?By heaven! I'll hate him everlastingly,That bids me be of comfort any more.Go, to Flint Castle, there I'll pine away;A king, woe's slave, shall kingly woe obey.Then, the investiture of the Castle—"Scene 3.—Wales—Before Flint Castle;" "Enter, with drums and colours, BOLINGBROKE and Forces." "A parle sounded, and answered.—Flourish.—Enter on the walls KING RICHARD, &c." Shakspeare makes the capture in the castle. Thus, Northumberland (from Bolingbroke before the castle) parleys with the King—

My lord, in the base court he doth attendTo speak with you, may't please you to come down?KING RICHARDDown, down I come; like glistering Phaeton,Wanting the management of unruly jades.(North retires to Boling.)In the base court? Base court, where kings grow base,To come at traitors' calls, and do them grace.In the base court? Come Down? Down Court, Down King!For night-owls shriek where mounting larks should sing.(Exeunt from above.)Richard has been described as a prince of surpassing beauty; but his mental powers did not correspond with his personal form, and his character was both weak and treacherous. He, however, had some redeeming points. His ordering some trees to be cut down at Sheen, because they too forcibly reminded him of his deceased wife Anne, in whose company he used to walk under them, affords a favourable testimony of his susceptibility of the social affections. Of this sensitiveness, there is also an interesting trait recorded by Froissart. From Flint Castle, Richard was conveyed to London, and immured within the Tower cells. While he was here one day conversing with Bolingbroke, his favourite greyhound, Math, having been loosed by his keeper, instead of running to the King, as usual, fawned upon the Duke. The latter inquiring the cause of this unusual circumstance, was answered—"This greyhound fondles and pays his court to you this day as King of England, which you will surely be, and I shall be deposed."

To return to Flint Castle. After the civil wars under Charles I. it was ordered to be dismantled; but, among other rights, it was restored to Sir Roger Mostyn, after the Restoration, in whose family it is still vested, though the mayor of the borough acts as its constable.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

WEBER AND DER FREISCHUTZ

In 1821, the newly-erected Royal Opera at Berlin was opened with "Der Freyschütz." The effect produced by the first representation of this romantic opera, which we shall never cease to regard as one of the proudest achievements of genius, was almost unprecedented. It was received with general acclamations, and raised his name at once to the first eminence in operatic composition. In January it was played in Dresden, in February at Vienna, and everywhere with the same success.—Weber alone seemed calm and undisturbed amid the general enthusiasm. He pursued his studies quietly, and was already deeply engaged in the composition of a comic opera, "The Three Pintos," never completed, and had accepted a commission for another of a romantic cast for the Vienna stage. The text was at first to have been furnished by Rellstab, but was ultimately written by Madame de Chezy, and written in so imperfect and impracticable a style, that, with all Rellstab's alterations never had a musician more to contend with than poor Weber had to do with this old French story. As it is, however, he has caught the spirit of the tale.

"Dance and Provençal song, and vintage mirth"breathe in his melodies; and although a perplexed plot and want of interest in the scene greatly impaired its theatrical effect, the approbation with which it was notwithstanding received by all judges of music on its first representation in Vienna (10th Oct. 1823) sufficiently attested the triumph of the composer over his difficulties. He was repeatedly called for and received with the loudest acclamations. From Vienna, where he was conducting his Euryanthe, he was summoned to Prague, to superintend the fiftieth representation of his "Freyschütz." His tour resembled a triumphal procession; for, on his return to Dresden, he was greeted with a formal public reception in the theatre.

But while increasing in celebrity, and rising still higher, if that were possible, in the estimation of the public, his health was rapidly waning, amidst his anxious and multiplied duties. "Would to God," says he in a letter written shortly afterwards—"Would to God that I were a tailor, for then I should have a Sunday's holiday!" Meantime a cough, the herald of consumption, tormented him, and "the slow minings of the hectic fire" within began to manifest themselves more visibly in days and nights of feverish excitement. It was in the midst of this that he accepted the task of composing an opera for Covent Garden Theatre. His fame, which had gradually made its way through the North of Germany (where his Freyschütz was played in 1823) to England, induced the managers to offer him liberal terms for an opera on the subject of Oberon, the well-known fairy tale on which Wieland has reared his fantastic, but beautiful and touching comic Epos. He received the first act of Planché's manuscript in December, 1824, and forthwith began his labours, though he seems to have thought that the worthy managers, in the short time they were disposed to allow him, were expecting impossibilities, particularly as the first step towards its composition, on Weber's part, was the study of the English language itself, the right understanding of which, Weber justly considered as preliminary to any attempt to marry Mr. Planché's ephemeral verses to his own immortal music. These exertions increased his weakness so much, that he found it necessary to resort to a watering-place in the summer of 1825. In December he returned to Berlin, to bring out his Euryanthe there in person. It was received, as might have been anticipated, with great applause, though less enthusiastically than the Freyschütz, the wild and characteristic music of which, came home with more intensity to the national mind. After being present at two representations, he returned to his labours at Oberon.

The work, finally, having been completed, Weber determined himself to be present at the representation of this his last production. He hoped, by his visit to London, to realize something for his wife and family; for hitherto, on the whole, poverty had been his companion. Want had, indeed, by unceasing exertion, been kept aloof, but still hovering near him, and threatening with the decline of his health, and his consequent inability to discharge his duties, a nearer and a nearer approach. Already he felt the conviction that his death was not far off, and that his wife and children would soon be deprived of that support which his efforts had hitherto afforded them. His intention was to return from London by Paris, where he expected to form a definitive arrangement relative to an opera which the Parisians had long requested from him.

On the 2nd of March he left Paris for England, which he reached on the 4th amidst a heavy shower of rain—a gloomy opening to his visit. The first incident, however, that happened after his arrival, showed how highly his character and talents were appreciated. Instead of requiring to present himself as an alien at the Passport Office, he was immediately waited upon by the officer with the necessary papers, and requested to think of nothing but his own health, as everything would be managed for him. On the 6th he writes to his wife from London:

"God be thanked! here I sit, well and hearty, already quite at home, and perfectly happy in the receipt of your dear letter, which assures me that you and the children are well; what more or what better could I wish for? After sleeping well and paying well at Dover, we set out yesterday morning in the Express coach, a noble carriage, drawn by four English horses, such as no prince need be ashamed of. With four persons within, four in front, and four behind, we dashed on with the rapidity of lightning, through this inexpressibly beautiful country: meadows of the loveliest green, gardens blooming with flowers, and every building displaying a neatness and elegance which form a striking contrast to the dirt of France. The majestic river, covered with ships of all sizes (among others, the largest ship of the line, of 148 guns), the graceful country houses, altogether made the journey perfectly unique."

He took up his residence with Sir George Smart, where everything that could add to his comfort, or soothe his illness, had been provided by anticipation. He found his table covered with cards from visiters who had called before his arrival, and a splendid pianoforte in his room from one of the first makers, with a request that he would make use of it during his stay.

"The whole day," he writes to his wife, "is mine till five—then dinner, the theatre, or society. My solitude in England is not painful to me. The English way of living suits mine exactly; and my little stock of English, in which I make tolerable progress, is of incalculable use to me.

"Give yourself no uneasiness about the opera (Oberon), I shall have leisure and repose here, for they respect my time. Besides, the Oberon is not fixed for Easter Monday, but some time later; I shall tell you afterwards when. The people are really too kind to me. No king ever had more done for him out of love; I may almost say they carry me in their arms. I take great care of myself, and you may be quite at ease on my account. My cough is really a very odd one; for eight days it disappeared entirely; then, upon the 3rd (of March) a vile spasmodic attack returned before I reached Calais. Since that time it is quiet again. I cannot, with all the consideration I have given it, understand it at all. I sometimes deny myself every indulgence, and yet it comes. I eat and drink every thing, and it does not come. But be it as God will.

"At seven o'clock in the evening we went to Covent Garden, where Rob Roy, an opera after Sir Walter Scott's novel, was played. The house is handsomely decorated, and not too large. When I came forward to the front of the stage-box, that I might have a better look of it, some one called out, Weber! Weber is here!—and although I drew back immediately, there followed a clamour of applause which I thought would never have ended. Then the overture to the Freyschütz was called for, and every time I showed myself the storm broke loose again. Fortunately, soon after the overture, Rob Roy began, and gradually things became quiet.—Could a man wish for more enthusiasm, or more love? I must confess that I was completely overpowered by it, though I am of a calm nature, and somewhat accustomed to such scenes. I know not what I would have given to have had you by my side, that you might have seen me in my foreign garb of honour. And now, my dear love, I can assure you that you may be quite at ease, both as to the singers and the orchestra. Miss Paton is a singer of the first rank, and will play Reiza divinely; Braham not less so, though in a totally different style. There are also several good tenors; and I really cannot see why the English singing should be so much abused. The singers have a perfectly good Italian education, fine voices, and expression. The orchestra is not remarkable, but still very good, and the choruses particularly so. In short, I feel quite at ease as to the fate of Oberon."

The final production of the drama, however, was attended with more difficulty than he had anticipated. He had the usual prejudices to overcome, particular singers to conciliate, alterations to make, and repeated rehearsals to superintend, before he could inspire the performers with the proper spirit of the piece.

"Braham," says he, "in another of his confidential letters to his wife," (29th March, 1826) "begs for a grand scena instead of his first air, which, in fact, was not written for him, and is rather high. The thought of it was at first quite horrible; I could not hear of it. At last I promised, when the opera was completed, if I had time enough, it should be done; and now this grand scena, a confounded battle piece and what not, is lying before me, and I am about to set to work, yet with the greatest reluctance. What can I do? Braham knows his public, and is idolized by them. But for Germany I shall keep the opera as it is. I hate the air I am going to compose (to-day I hope) by anticipation. Adieu, and now for the battle. * * * * So, the battle is over, that is to say, half the scene. To-morrow shall the Turks roar, the French shout for joy, the warriors cry out victory!"

The battle was, indeed, nearly over with Weber. The tired forces of life, though they bore up gallantly against the enemy, had long been wavering at their post, and now in fact only one brilliant movement remained to be executed before they finally retreated from the field of existence. This was the representation of Oberon, which for a time rewarded him for all his toils and vexations. He records his triumph with a mixture of humility, gratitude, affection, and piety.

"12th April, 1826.

"My best beloved Caroline! Through God's grace and assistance, I have this evening met with the most complete success. The brilliancy and affecting nature of the triumph is indescribable. God alone be thanked for it! When I entered the orchestra, the whole of the house, which was filled to overflowing, rose up, and I was saluted with huzzas, waving of hats and handkerchiefs, which I thought would never have done. They insisted on encoring the overture. Every air was interrupted twice or thrice by bursts of applause. * * * So much for this night, dear life. From your heartily tired husband, who, however, could not sleep in peace until he had communicated to you this new blessing of heaven. Good-night."

But his joy was interrupted by the gradual decline of his health. The climate of London brought back all those symptoms which his travelling had for a time alleviated or dissipated. After directing twelve performances of his Oberon in crowded houses, he felt himself completely exhausted and dispirited.—His melancholy was not abated by the ill success of his concert, which, from causes which we cannot pretend to explain, was no benefit to the poor invalid. His next letters are in a desponding tone.

"17th April, 1826.

"To-day is enough to be the death of any one. A thick, dark, yellow fog overhangs the sky, so that one can hardly see in the house without candles. The sun stands powerless, like a ruddy point, in the clouds. No: there is no living in this climate. The longing I feel for Hosterwitz, and the clear air, is indescribable. But patience,—patience,—one day rolls on after another; two months are already over. I have formed an acquaintance with Dr. Kind, a nephew of our own Kind. He is determined to make me well. God help me, that will never happen to me in this life. I have lost all hope in physicians and their art. Repose is my best doctor, and henceforth it shall be my sole

"To-morrow is the first representation of my (so called) rival's opera, 'Aladdin.' I am very curious to see it. Bishop is a man of talent, though of no peculiar invention. I wish him every success. There is room enough for all of us in the world."

"30th May.

"Dearest Lina, excuse the shortness and hurry of this. I have so many things on hand, writing is painful to me—my hands tremble so. Already too impatience begins to awaken in me. You will not receive many more letters from me. Address your answer not to London, but to Frankfort—poste restante. You are surprised? Yes, I don't go by Paris. What should I do there—I cannot move—I cannot speak–all business I must give up for years. Then better, better, the straight way to my home—by Calais, Brussels, Cologne, and Coblentz, up the Rhine to Frankfort—a delightful journey. Though I must travel slowly, rest sometimes half a day, I think in a fortnight, by the end of June, I shall be in your arms.

"If God will, we shall leave this on 12th June, if heaven will vouchsafe me a little strength. Well, all will go better if we are once on the way—once out of this wretched climate. I embrace you from my heart, my dear ones—ever your loving father Charles."

This letter, the last but one he ever wrote, shows the rapid decline of his strength, though he endeavours to keep up the spirits of his family by a gleam of cheerfulness. His longing for home now began to increase till it became a pang. On the 6th of June he was to be present at the Freyschütz, which was to be performed for his benefit, and then to leave London for ever. His last letter, the thirty-third he had written from England, was dated the second of June. Even here, though he could scarcely guide the pen, anxious to keep up the drooping spirits of his wife, he endeavours to speak cheerfully, and to inspire a hope of his return.

"As this letter will need no answer, it will be short enough. Need no answer! Think of that! Furstenau has given up the idea of his concert, so perhaps we shall be with you in two days sooner—huzza! God bless you all and keep you well! O were I only among you! I kiss you in thought, dear mother. Love me also, and think always of your Charles, who loves you above all."

On Friday the 3rd of June, he felt so ill, that the idea of his attending at the representation of "Der Freyschütz" was abandoned, and he was obliged to keep his room. On Sunday evening, the 5th, he was left at eleven o'clock in good spirits, and at seven next morning was found dead upon his pillow, his head resting upon his hand, as though he had passed from life without a struggle. The peaceful slumber of the preceding evening seemed to have gradually deepened into the sleep of death.