полная версия

полная версияThe Bay State Monthly. Volume 1, No. 5, May, 1884

Our New England town-house, therefore, is a symbol of institutions, partly original with our fathers, partly a priceless inheritance from Old England the land of our fathers, and nearly in the whole, if not quite, a regermination and new growth of old race instincts and practices on a new soil.

The New England town is not an institution of all the States, but its principle has invaded the majority. To the West and Northwest it has been carried by the New Englander himself, and is being carried by him both directly and indirectly into the South and Southwest, and will show there in no great length of time its prevailing and vitalizing power.

It was Jefferson, himself a Virginian, reared in the midst of another system, aristocratical and central in its character, who said: "These wards, called townships in New England, are the vital principle of their governments, and have proved themselves the wisest invention ever devised by the wit of man for the perfect exercise of self-government and for its preservation."

The New England town-house, therefore, is significant of more than its predecessor in England or Germany. While with them it means freedom in the management of local affairs, beyond them it means a relation to the State and the National government which they did not. It means not merely a broad basis for the general government in the people, that the people are the reason and remote source of governing power, but that they are themselves the governors. Every man who enters a New England town-house and casts his vote knows that that expression of his will is a force which reaches, or may reach, the Legislature of his State, the governor in his chair, the National Congress, and the President in the White House at Washington. He feels an interest therefore, and a responsibility which the voter in no other land in the world feels, and the town-house is an education to him in the art of self-government which no other country affords, and because of it the town is an institution teaching how to maintain government, local, state, and general, and so bases that government in self-interest and beneficial experience, that it is a pledge of security and perpetuity as regards socialism, communism, and as it would seem every other revolutionary influence from within. It is in strong contrast with the commune of France. France is divided for the purposes of local government into departments; departments into arrondissements; and arrondissements into communes, the commune being the administrative unit. The department is governed by a préfet and a conseil-général, the préfet being appointed by the central government and directly under its control, and the conseil-général an elective body. The arrondissement is presided over by a sous-préfet and an elective council. The commune is governed by a maire and a conseil-municipal.

The conseil-municipal is an elective body, but its duties "consist in assisting and to some extent controlling the maire, and in the management of the communal affairs," but the maire is appointed by the central government and is liable to suspension by the préfet.

The relation of the citizen to the general government in France is therefore totally different from that of the citizen of the United States to his general government, and the town organization is a school of free citizenship which the commune is not, and so far republican institutions in America have a guaranty which in France they have not.

BUNKER HILL

[(a) The occupation of Charlestown Heights on the night of June 16, 1775, was of strategic value, however transient, equalizing the relations of the parties opposed, and projecting its force and fire into the entire struggle for American Independence. (Pages 290-302.)

(b)The Siege of Boston, which followed, gave to the freshly organized Continental army that discipline, that instruction in military engineering, and that contact with a well-trained enemy which prepared it for immediate operations at New York and in New Jersey. (Pages 37-44.)

(c) The occupation and defence of New York and Brooklyn, so promptly made, was also an immediate strategic necessity, fully warranted by the existing conditions, although alike temporary. (Pages 34-161.)]

An exhaustless theme may be so outlined that fairly stated data will suggest the possibilities beyond.

Waterloo is incidentally related to the crowning laurels of Wellington; but, primarily, to the downfall of Napoleon, while rarely to the assured growth of genuine popular liberty.

No battle during the American Rebellion of 1861-65 was so really decisive as was the first battle of Bull's Run. As that Federal failure enforced the issue which freed four millions of people from slavery, and had its sequence and culmination, through great struggle, in a perpetuated Union, so did the battle of Bunker Hill open wide the breach between Great Britain and the Colonies, and render American Independence inevitable.

The repulse of Howe at Breed's Hill practically ejected him from Boston, enforced his halt before Brooklyn, delayed him at White Plains, explained his hesitation at Bound Brook, near Somerset Court-House, in 1777, as well as his sluggishness after the battle of Brandywine, and equally induced his inaction at Philadelphia, in 1778.

Just as a similar resistance by Totleben at Sevastapol during the Crimean War prolonged that struggle for twelve months, so did the hastily constructed earthworks on Breed's Hill forewarn the assailants that every ridge might serve as a fortress, and every sand-hill become a cover, for a persistent and earnest foe.

Historical research and military criticism suggest few cases where so much has been realized by the efforts of a few men, in a few hours, during the shelter of one night, and by the light of one day.

The simple narrative has been the subject of much discussion. Its details have been shaped and colored, with supreme regard for the special claims of preferred candidates for distinction, until a plain consideration of the issue then made, from a purely military point of view, as introductory to a detail of the battle itself, cannot be barren of interest to the readers of a Magazine which treats largely of the local history of Massachusetts.

The city of Boston was girdled by rapidly increasing earthworks. These were wholly defensive, to resist assault from the British garrison, and not, at first, as cover for a regular siege approach against the Island Post. They soon became a direct agency to force the garrison to look to the sea alone for supplies or retreat.

Open war against Great Britain began with this environment of Boston. The partially organized militia responded promptly to call.

The vivifying force of the struggle through Concord, Lexington, and West Cambridge (Arlington now), had so quickened the rapidly augmenting body of patriots, that they demanded offensive action and grew impatient for results. Having dropped fear of British troops, as such, they held a strong purpose to achieve that complete deliverance which their earnest resistance foreshadowed.

Lexington and Concord were, therefore, the exponents of that daring which made the occupation and resistance of Breed's Hill possible. The fancied invincibility of British discipline went down before the rifles of farmers; but the quickening sentiment, which gave nerve to the arm, steadiness to the heart, and force to the blow, was one of those historic expressions of human will and faith, which, under deep sense of wrong incurred and rights imperilled, overmasters discipline, and has the method of an inspired madness. The moral force of the energizing passion became overwhelming and supreme. No troops in the world, under similar conditions, could have resisted the movement.

The opposing forces did not alike estimate the issue, or the relations of the parties in interest. The troops sent forth to collect or destroy arms, rightfully in the hands of their countrymen, and not to engage an enemy, were under an involuntary restraint, which stripped them of real fitness to meet armed men, who were already on fire with the conviction that the representatives of national force were employed to destroy national life.

The ostensible theory of the Crown was to reconcile the Colonies. The actual policy, and its physical demonstrations, repelled, and did not conciliate. Military acts, easily done by the force in hand, were needlessly done. Military acts which would be wise upon the basis of anticipated resistance were not done.

Threats and blows toward those not deemed capable of resistance were freely expended. Operations of war, as against an organized and skilful enemy, were ignored. But the legacies of English law and the inheritance of English liberty had vested in the Colonies. Their eradication and their withdrawal were alike impossible. The time had passed for compromise or limitation of their enjoyment. The filial relation toward England was lost when it became that of a slave toward master, to be asserted by force. This the Americans understood when they environed Boston. This the British did not understand, until after the battle of Bunker Hill. The British worked as against a mob of rebels. The Americans made common cause, "liberty or death," against usurpation and tyranny.

THE OUTLOOK

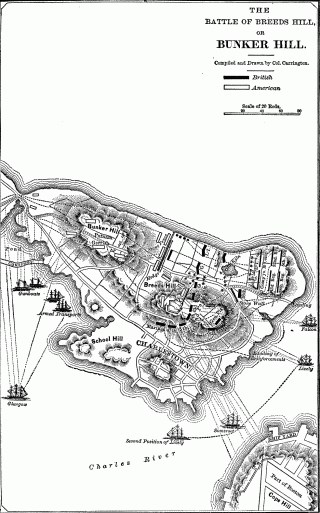

Reference to map, "Boston and vicinity," already used in the January number of this Magazine to illustrate the siege of Boston, will give a clear impression of the local surroundings, at the time of the American occupation of Charlestown Heights. The value of that position was to be tested. The Americans had previously burned the lighthouses of the harbor. The islands of the bay were already miniature fields of conflict; and every effort of the garrison to use boats, and thereby secure the needed supplies of beef, flour, or fuel, only developed a counter system of boat operations, which neutralized the former and gradually limited the garrison to the range of its guns. This close grasp of the land approaches to Boston, so persistently maintained, stimulated the Americans to catch a tighter hold, and force the garrison to escape by sea. The capture of that garrison would have placed unwieldy prisoners in their hands and have made outside operations impossible, as well as any practical disposition of the prisoners themselves, in treatment with Great Britain. Expulsion was the purpose of the rallying people.

General Gage fortified Boston Neck as early as 1774, and the First Continental Congress had promptly assured Massachusetts of its sympathy with her solemn protest against that act. It was also the intention of General Gage to fortify Dorchester Heights. Early in April, a British council of war, in which Clinton, Burgoyne, and Percy took part, unanimously advised the immediate occupation of Dorchester, as both indispensable to the protection of the shipping, and as assurance of access to the country for indispensable supplies.

General Howe already appreciated the mistake of General Gage, in his expedition to Concord, but still cherished such hope of an accommodation of the issue with the Colonies that he postponed action until a peaceable occupation of Dorchester Heights became impossible, and the growing earthworks of the besiegers already commanded Boston Neck.

General Gage had also advised, and wisely, the occupation of Charlestown Heights, as both necessary and feasible, without risk to Boston itself. He went so far as to announce that, in case of overt acts of hostility to such occupation, by the citizens of Charlestown, he would burn the town.

It was clearly sound military policy for the British to occupy both Dorchester and Charlestown Heights, at the first attempt of the Americans to invest the city.

As early as the middle of May, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, as well as the council, had resolved "to occupy Bunker Hill as soon as artillery and powder could be adequately furnished for the purpose," and a committee was appointed to examine and report respecting the merits of Dorchester Heights, as a strategic restraint upon the garrison of Boston.

On the fifteenth of June, upon reliable information that the British had definitely resolved to seize both Heights, and had designated the eighteenth of June for the occupation of Charlestown, the same Committee of Safety voted "to take immediate possession of Bunker Bill."

Mr. Bancroft states that "the decision was so sudden that no fit preparation could be made," Under the existing conditions, it was indeed a desperate daring, expressive of grand faith and self-devotion, worthy of the cause in peril, and only limited in its immediate and assured triumph by the simple lack of powder.

Prescott, who was eager to lead the enterprise and was entrusted with its execution, and Putman, who gave it his most ardent support, were most urgent that the council should act promptly; while Warren, who long hesitated to concur, did at last concur, and gave his life as the test of his devotion. General Ward realized fully that the hesitation of the British to emerge from Boston and attack the Americans was an index of the security of the American defences, and, therefore, deprecated the contingency of a general engagement, until ample supplies of powder could be secured.

The British garrison, which had been reinforced to a nominal strength of ten thousand men, had become reduced, through inadequate supplies, especially of fresh meat, to eight thousand effectives, but these men were well officered and well disciplined.

THE POSITION

Bunker Hill had an easy slope to the isthmus, but was quite steep on either side, having, in fact, control of the isthmus, as well as commanding a full view of Boston and the surrounding country. Morton's Hill, at Moulton's Point, where the British landed, was but thirty-five feet above sea level, while Breed's Pasture (as then known) and Bunker Hill were, respectively, seventy-five and one hundred and ten feet high. The Charles and Mystic Rivers, which flanked Charlestown, were navigable, and were under the control of the British ships-of-war.

AMERICAN POLICY

To so occupy Charlestown, in advance, as to prevent a successful British landing, required the use of the nearest available position that would make the light artillery of the Americans effective. To occupy Bunker Hill, alone, would leave to the British the cover of Breed's Hill, under which to gain effective fire and a good base for approach, as well as Charlestown for quarters, without prejudice to themselves.

When, therefore, Breed's Hill was fortified as an advanced position, it was done with the assurance that reinforcements would soon occupy the retired summit, and the course adopted was the best to prevent an effective British lodgment. The previous reluctance of the garrison to make any effective demonstration against the thin lines of environment strengthened the belief of the Americans that a well-selected hold upon Charlestown Heights would securely tighten the grasp upon the city itself.

BRITISH POLICY

As a fact, the British contempt for the Americans might have urged them as rashly against Bunker Hill as it did against the redoubt which they gained, at last, only through failure of the ammunition of its defenders; but, in view of the few hours at disposal of the Americans to prepare against a landing so soon to be attempted, it is certain that the defences were well placed, both to cover the town and force an immediate issue before the British could increase their own force.

It is equally certain that the British utterly failed to appreciate the fact that, with the control of the Mystic and Charles Rivers, they could, within twenty-four hours, so isolate Charlestown as to secure the same results as by storming the American position, and without appreciable loss. This was the advice of General Clinton, but he was overruled. They did, ultimately, thereby check reinforcements, but suffered so severely in the battle itself that fully two thirds of the Americans retired safely to the main land.

The delay of the British to advance as soon as the landing was effected was bad tactics. One half of the force could have followed the Mystic and turned the American left wing, long before Colonel Stark's command came upon the field. The British dined as leisurely as if they had only to move any time and seize the threatening position, and thereby lost their chief opportunity.

One single sign of the recognition of any possible risk-to themselves was the opening of fire from Boston Neck and such other positions as faced the American lines, as if to warn them not to attempt the city, or endanger their own lives by sending reinforcements to Charlestown.

THE MOVEMENT

It is not the purpose of this article to elaborate the details of preparation, which have been so fully discussed by many writers, but to illustrate the value of the action in the light of the relations and conduct of the opposing forces.

Colonel William Prescott, of Pepperell, Massachusetts, Colonel James Frye, of Andover, and Colonel Ebenezer Bridge, of Billerica, whose regiments formed most of the original detail, were members of the council of war which had been organized on the twentieth of April, when General Ward assumed command of the army. Colonel Thomas Knowlton, of Putnam's regiment, was to lead a detachment from the Connecticut troops. Colonel Richard Gridley, chief engineer, with a company of artillery, was also assigned to the moving columns.

To ensure a force of one thousand men, the field order covered nearly fourteen hundred, and Mr. Frothingham shows clearly that the actual force as organized, with artificers and drivers of carts, was not less than twelve hundred men.

Cambridge Common was the place of rendezvous, where, at early twilight of June 16, the Reverend Samuel Langdon, president of Harvard College, invoked the blessing of Almighty God upon the solemn undertaking.

This silent body of earnest men crossed Charlestown Neck, and halted for a clear definition of the impending duty. Major Brooks, of Colonel Dodge's regiment, joined here, as well as a company of artillery. Captain Nutting, with a detachment of Connecticut men, was promptly sent, by the quickest route, to patrol Charlestown, at the summit of Bunker Hill. Captain Maxwell's company, of Prescott's regiment, was next detailed to patrol the shore in silence and keenly note any activity on board the British men-of-war.

The six vessels lying in the stream were the Somerset, sixty-eight, Captain Edward Le Cross; Cerberus, thirty-six, Captain Chads; Glasgow, thirty-four, Captain William Maltby; Lively, twenty, Captain Thomas Bishop; Falcon, twenty, Captain Linzee, and the Symmetry, transport, with eighteen guns.

While one thousand men worked upon the redoubt which had been located under counsel of Gridley, Prescott, Knowlton, and other officers, the dull thud of the pickaxe and the grating of shovels were the only sounds that disturbed the pervading silence, except as the sentries' "All's well!" from Copp's Hill and from the warships, relieved anxiety and stimulated work. Prescott and Putnam alike, and more than once, visited the beach, to be assured that the seeming security was real; and at daybreak the redoubt, nearly eight rods square and six feet high, was nearly complete.

Scarcely had objects become distinct, when the battery on Copp's Hill and the guns of the Lively opened fire, and startled the garrison of Boston from sleep, to a certainty that the Colonists had taken the offensive.

General Putnam reached headquarters at a very early hour, and secured the detail of a portion of Colonel Stark's regiment, to reinforce the first detail which had already occupied the Hill.

At nine o'clock, a council of war was held at Breed's Hill. Major John Brooks was sent to ask for more men and more rations. Richard Devens, of the Committee of Safety, then in session, was influential in persuading General Ward to furnish prompt reinforcements. By eleven o'clock, the whole of Stark's and Reed's New Hampshire regiments were on their march, and in time to meet the first shock of battle. Portions of other regiments hastened to the aid of those already waiting for the fight to begin.

The details of men were not exactly defined, in all cases, when the urgent call for reinforcements reached headquarters. Little's regiment of Essex men; Brewer's, of Worcester and Middlesex, with their Lieutenant-Colonel Buckminster; Nixon's, led by Nixon himself; Moore's, from Worcester; Whitcomb's, of Lancaster, and others, promptly accepted the opportunity to take part in the offensive, and challenge the British garrison to a contest-at-arms, and well they bore their part in the struggle.

THE AMERICAN POSITION

The completion of the redoubt only made more distinct the necessity for additional defences. A line of breastworks, a few rods in length, was carried to the left, and then to the rear, in order to connect with a stone fence which was accepted as a part of the line, since the fence ran perpendicularly to the Mystic; and the intention was to throw some protection across the entire peninsula to the river. A small pond and some spongy ground were left open, as non-essential, considering the value of every moment; and every exertion was made for the protection of the immediate front. The stone fence, like those still common in New England, was two or three feet high, with set posts and two rails; in all, about five feet high, the top rail giving a rest for a rifle. A zigzag "stake and rider fence" was put in front, the meadow division-fences being stripped for the purpose. The fresh-mown hay filled the interval between the fences. This line was nearly two hundred yards in rear of the face of the redoubt, and near the foot of Bunker Hill. Captain Knowlton, with two pieces of artillery and Connecticut troops, was assigned, by Colonel Prescott, to the right of this position, adjoining the open gap already mentioned. Between the fence and the river, more conspicuous at low tide, was a long gap, which was promptly filled by Stark as soon as he reached the ground, thus, as far as possible, to anticipate the very flanking movement which the British afterward attempted.

Putnam was everywhere active, and, after the fences were as well secured as time would allow, he ordered the tools taken to Bunker Hill for the establishment of a second line on higher ground, in case the first could not be maintained. His importunity with General Ward had secured the detail of the whole of Reed's, as well as the balance of Stark's, regiment, so that the entire left was protected by New Hampshire troops. With all their energy they were able to gather from the shore only stone enough for partial cover, while they lay down, or kneeled, to fire.

The whole force thus spread out to meet the British army was less than sixteen hundred men. Six pieces of artillery were in use at different times, but with little effect. The cannon cartridges were at last distributed for the rifles, and five of the guns were left on the field when retreat became inevitable.

Reference to the map will indicate the position thus outlined. It was evident that the landing could not be prevented. Successive barges landed the well-equipped troops, and they took their positions, and their dinner, under the blaze of the hot sun, as if nothing but ordinary duty was awaiting their leisure.

THE BRITISH ADVANCE

It was nearly three o'clock in the afternoon when the British army formed for the advance. General Howe was expected to break and envelop the American left wing, take the redoubt in the rear, and cut off retreat to Bunker Hill and the mainland. The light infantry moved closely along the Mystic. The grenadiers advanced upon the stone fence, while the British left demonstrated toward the unprotected gap which was between the fence and the short breastwork next the redoubt. General Pigot with the extreme left wing moved directly upon the redoubt. The British artillery had been supplied with twelve-pound shot for six-pounder guns, and, thus disabled, were ordered to use only grape. The guns were, therefore, advanced to the edge of an old brick-kiln, as the spongy ground and heavy grass did not permit ready handling of guns at the foot of the hill slope, or even just at its left. This secured a more effective range of fire upon the skeleton defences of the American centre, and an eligible position for a direct fire upon the exposed portion of the American front, and both breastwork and redoubt.