полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 335, October 11, 1828

ENCOMIUM MORIÆ, OR THE PRAISE OF FOLLY

If from our purse all coin we spurnBut gold, we may from mart return.Nor purchase what we’re seeking;And if in parties we must talkNothing but sterling wit, we balkAll interchange of speaking.Small talk is like small change; it flowsA thousand different ways, and throwsThoughts into circulation,Of trivial value each, but whichCombin’d, make social converse richIn cheerful animation.As bows unbent recruit their force.Our minds by frivolous discourseWe strengthen and embellish,“Let us be wise,” said Plato once,When talking nonsense—“yonder dunceFor folly has no relish.”The solemn bore, who holds that speechWas given us to prose and preach,And not for lighter usance,Straight should be sent to Coventry;Or omnium concensu, beIndicted as a nuisance.Though dull the joke, ‘tis wise to laugh,Parch’d be the tongue that cannot quaffSave from a golden chalice;Let jesters seek no other plea,Than that their merriment be freeFrom bitterness and malice.Silence at once the ribald clown.And check with an indignant frownThe scurrilous backbiter;But speed good-humour as it runs,Be even tolerant of puns,And every mirth-exciter.The wag who even fails may claimIndulgence for his cheerful aim;We should applaud, not hiss him;This is a pardon which we grant,(The Latin gives the rhime I want,)“Et petimus vicissim.”Ibid.Your love is like the gnats, John,That hum at close of day:That sting, and leave a scar behind,Then sing and fly away.Weekly Review.VILLANOVA MILL

The Portuguese mills have a very extraordinary appearance, owing chiefly to the shape of their arms or sails, the construction of which differs from that of all other mills in Europe.

Villanova de Milfontès is a little town, situated at the mouth of a little river which flows from the Sierra de Monchique. Formerly there was a port here, formed by a little bay, and defended by a castle, which might have been of some importance at a period when the Moors made such frequent incursions upon the coasts of the kingdom of the Algarves; at present a dangerous bar and banks of quicksands hinder any vessels larger than small fishing-boats from entering the port.

Fig trees from 20 to 30 feet high overshadow the moat of the castle, and aloes plants as luxuriant as those of Andalusia, shoot up their stems crowned with flowers along the shores of the bay, and by the sides of the roads, whose windings are lost amongst the gardens that surround Milfontès.

We have seen Mr. HAYDON’S PICTURE of the Chairing of the Members; but must defer our description till the next number of the MIRROR. In the meantime we recommend our readers to visit the exhibition, so that they may compare notes with us. “The Chairing” is even superior to the “Election.”

NOTES OF A READER

STORY OF RIENZI

(The original of Miss Mitford’s New Tragedy.)In the year 1437, an obscure man, Nicola di Rienzi, conceived the project of restoring Rome, then in degradation and wretchedness, not only to good order, but even to her ancient greatness. He had received an education beyond his birth, and nourished his mind with the study of the best writers. After many harangues to the people, which the nobility, blinded by their self-confidence, did not attempt to repress, Rienzi suddenly excited an insurrection, and obtained complete success. He was placed at the head of a new government, with the title of Tribune, and with almost unlimited power. The first effects of this revolution were wonderful. All the nobles submitted, though with great reluctance; the roads were cleared of robbers; tranquillity was restored at home; some severe examples of justice intimidated offenders; and the tribune was regarded by all the people as the destined restorer of Rome and Italy. Most of the Italian republics, and some of the princes, sent embassadors, and seemed to recognise pretensions which were tolerably ostentatious. The King of Hungary and Queen of Naples submitted their quarrel to the arbitration of Rienzi, who did not, however, undertake to decide it. But this sudden exaltation intoxicated his understanding, and exhibited feelings entirely incompatible with his elevated condition. If Rienzi had lived in our own age, his talents, which were really great, would have found their proper orbit, for his character was one not unusual among literary politicians; a combination of knowledge, eloquence, and enthusiasm for ideal excellence, with vanity, inexperience of mankind, unsteadiness, and physical timidity. As these latter qualities became conspicuous, they eclipsed his virtues, and caused his benefits to be forgotten: he was compelled to abdicate his government, and retire into exile. After several years, some of which he passed in the prison of Avignon, Rienzi was brought back to Rome, with the title of senator, and under the command of the legate. It was supposed that the Romans, who had returned to their habits of insubordination, would gladly submit to their favourite tribune. And this proved the case for a few months; but after that time they ceased altogether to respect a man who so little respected himself in accepting a station where he could no longer be free, and Rienzi was killed in a sedition.

“The doors of the capitol,” says Gibbon, “were destroyed with axes and with fire; and while the senator attempted to escape in a plebeian garb, he was dragged to the platform of his palace, the fatal scene of his judgments and executions;” and after enduring the protracted tortures of suspense and insult, he was pierced with a thousand daggers, amidst the execrations of the people.

At Rome is still shown a curious old brick dwelling, distinguished by the appellation of “The House of Pilate,” but known to be the house of Rienzi. It is exactly such as would please the known taste of the Roman tribune, being composed of heterogeneous scraps of ancient marble, patched up with barbarous brick pilasters of his own age; affording an apt exemplification of his own character, in which piecemeal fragments of Roman virtue, and attachment to feudal state—abstract love of liberty, and practice of tyranny—formed as incongruous a compound.

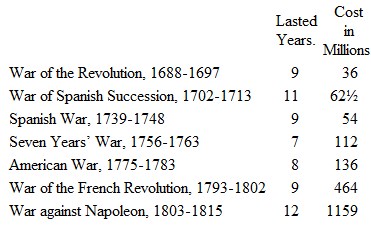

ENGLISH WARS

A pamphlet, entitled, A Call upon the People of Great Britain and Ireland, has lately reached us; but as its contents are purely political, we must content ourselves with a few historical data. Thus, of the 127 years from the Revolution to 1815, 65 have passed in war, during which “high trials of right,” 2,023½ millions have been expended in seven wars. Of these we give a synopsis:

Of this expenditure we borrowed 834½ millions, and raised by taxes 1,189 millions. During the 127 years, the annual poor-rates rose from ¾ of a million to 5½ millions, and the price of wheat from 44s. to 92s. 8d. per quarter.

But it is time to clear the table, for it “strikes us more dead than a great reckoning in a little room.”

CHAIN OF BEING

Our thanks are due to Mr. Dillon for a copy of the second edition of his Popular Premises Examined, which we have read with considerable interest. The “opinions” are as popularly examined as is consistent with philosophical inquiry; but they are still not just calculated for the majority of the readers of the MIRROR. We, nevertheless, make one short extract, which will be acceptable to every well-regulated mind; and characteristic of the tone of good-feeling throughout Mr. Dillon’s important little treatise.

“The spheres which we behold may each have their variety of intelligent ‘being,’ as links in nature’s beautiful chain, connecting the smallest insect with the incomprehensible and immutable God. The beautiful variety we see in his works portrays His will, and we are justified in following this variety up to His throne. His attributes of love and joy beam forth from the heavens, and are reflected from every species of sensitive being. All have different capacities for enjoyment, all have pleasure and delight, from the lark warbling above her nest, to man walking in the resplendent gardens of heaven, and enjoying, under the smiling approbation of Providence, the flowers and fruits that surround him.”

No man without the support and encouragement of friends, and having proper opportunities thrown in his way, is able to rise at once from obscurity, by the force of his own unassisted genius.—Pliny’s Letters.

RABBIS

Constitute a sort of nobility of the Jews, and it is the first object of each parent that his sons shall, if possible, attain it. When, therefore, a boy displays a peculiarly acute mind and studious habits, he is placed before the twelve folio volumes of the Talmud, and its legion of commentaries and epitomes, which he is made to pore over with an intenseness which engrosses his faculties entirely, and often leaves him in mind, and occasionally in body, fit for nothing else; and so vigilant and jealous a discipline is exercised so to fence him round as to secure his being exclusively Talmudical, and destitute of every other learning and knowledge whatever, that one individual has lately met with three young men, educated as rabbis, who were born and lived to manhood in the middle of Poland, and yet knew not one word of its language. To speak Polish on the Sabbath is to profane it—so say the orthodox Polish Jews. If at the age of fourteen or fifteen years, or still earlier, (for the Jew ceases to be a minor when thirteen years old,) this Talmudical student realizes the hopes of his childhood, he becomes an object of research among the wealthy Jews, who are anxious that their daughters shall attain the honour of becoming the brides of these embryo santons; and often, when he is thus young, and his bride still younger, the marriage is completed.

BARBER-SURGEONS

Jacob de Castro was one of the first members of the Corporation of Surgeons, after their separation from the barbers in the year 1745. On which occasion Bonnel Thornton suggested “Tollite Barberum” for their motto.

The barber-surgeons had a by-law, by which they levied ten pounds on any person who should dissect a body out of their hall without leave. The separation did away this and other impediments to the improvement of surgery in England, which previously had been chiefly cultivated in France. The barber-surgeon in those days was known by his pole, the reason of which is sought for by a querist in “The British Apollo,” fol. Lond. 1708, No. 3:—

“I’de know why he that selleth aleHangs out a chequer’d part per pale;And why a barber at port-holePuts forth a party-colour’d pole?”ANSWER“In ancient Rome, when men lov’d fighting,And wounds and scars took much delight in,Man-menders then had noble pay,Which we call surgeons to this day.‘Twas order’d that a huge long pole,With basen deck’d, should grace the hole.To guide the wounded, who unloptCould walk, on stumps the others hopt;But, when they ended all their wars,And men grew out of love with scars,Their trade decaying, to keep swimming,They join’d the other trade of trimming;And to their poles, to publish either,Thus twisted both their trades together.”From Brand’s “History of Newcastle,” we find that there was a branch of the fraternity in that place; as at a meeting, 1742, of the barber-chirurgeons, it was ordered, that they should not shave on a Sunday, and “that no brother shave John Robinson, till he pay what he owes to Robert Shafto.” Speaking of the “grosse ignorance of the barbers,” a facetious author says, “This puts me in minde of a barber who, after he had cupped me, (as the physitian had prescribed,) to turn a catarrhe, asked me if I would be sacrificed. Scarified? said I; did the physitian tell you any such thing? No, (quoth he,) but I have sacrificed many, who have been the better for it. Then musing a little with myselfe, I told him, Surely, sir, you mistake yourself—you meane scarified. O, sir, by your favour, (quoth he,) I have ever heard it called sacrificing; and as for scarifying, I never heard of it before. In a word, I could by no means perswade him but that it was the barber’s office to sacrifice men. Since which time I never saw any man in a barber’s hands, but that sacrificing barber came to my mind.”—Wadd’s Nugæ.

Sir Theodore Mayerne may be considered one of the earliest reformers of the practice of physic. He left some papers written in elegant Latin, in the Ashmolean Collection, which contain many curious particulars relative to the first invention of several medicines, and the state of physic at that period. Petitot, the celebrated enameller, owed his success in colouring to some chemical secrets communicated to him by Sir Theodore.

He was a voluminous writer, and, among others, wrote a book of receipts in cookery. Many were the good and savoury things invented by Sir Theodore; his maxims, and those of Sir John Hill, under the cloak of Mrs. Glasse, might have directed our stew-pans to this hour, but for the more scientific instructions of the renowned Mrs. Rundall, or of the still more scientific Dr. Kitchiner, who has verified the old adage, that the “Kitchen is the handmaid to Physic;” and if it be true that we are to regard a “good cook as in the nature of a good physician,” then is Dr. Kitchiner the best physician that ever condescended to treat “de re culinaria.”

Sir Theodore may, in a degree, be said to have fallen a victim to bad cookery; for he is reported to have died of the effects of bad wine, which he drank at a tavern in the Strand. He foretold it would be fatal, and died, as it were, out of compliment to his own prediction.—Ibid.

THE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

THE COFFEE-DRINKER’S MANUAL

We would say of coffee-making in England, as Hamlet did of acting, “Oh, reform it altogether.” Accordingly, the publication of a pleasant trifle, under the above name, is not ill-timed. Like all our modern farces, it is from the French, and as the translator informs us, the editor of the original is “of the Café de Foi, at Paris.”

It opens with the History of Coffee, from its discovery by a monk in the 17th century, to the establishment of cafés in Paris, of which we have a brief notice, with additions by the translator.

Next is “the French method of making coffee, with the roasting, grinding, and infusion processes”; and an interesting chapter on “coffee in the East.” Under the “medicinal effects” we have the following, which is full of the gaiete de coeur of French writing:—

Influence of Coffee upon the Spirits. If coffee had been known among the Greeks and Romans, Homer would have taken his lyre to celebrate its virtues; Horace and Juvenal would have immortalized it in their verses; Diogenes would not have concealed his ill-humour in a tub, but would have drunk of this divine liquid, and have directly found the honest man he sought for; it would have made Heraclitus merry; and with what odes would it have inspired the muse of Anacreon!

In short, who can enumerate the wonderful effects of coffee!

Seest thou that morose figure, that pale complexion, those deadened eyes, and faded lips? It is a lamentable fit of spleen. The whole faculty have been sent for, but their art is unavailing. She is given over. Happily one of her friends counsels her against despair, prescribes a few cups of Moka, and the dying patient, being restored to health, concludes with anathematizing the faculty, who would thus have sacrificed her life.

The complexion of this young girl was, as the poets would say, of lilies and roses; never was there a form more celestial, or one more gifted with life and vigour.

Arrived at this stage, so fatal to the existence of females, the young girl sickened, lost her colour, and those cheeks, but yesterday so brilliant, were dull and heavy. “Travelling,” said one; “a husband,” said another; “coffee, coffee,” replied a doctor. Coffee flowed in abundance, and then the drooping flower revived, and flourished again.

O! all ye who have essayed at rhyme, say if you have not often derived your happiest thoughts from this inspiring beverage. Delille has some beautiful lines, and Berchoux, in his poem of Gastronomie, has a pompous eulogium on its virtues.

Coffee occupies a grand place in the life and pursuits of the gastronomer. Oft-times on leaving table his head aches and becomes heavy; he rises with pain; the savoury smells of viands, the flame of wax-lights, and the imperceptible gases which escape from innumerable wines and liqueurs, have produced around him a kind of mist or shade, equal to what the poet calls darkness visible. Coffee is quickly brought; our gastronomer inhales the aroma, sips drop by drop this ambrosian beverage, and his head already lightened, he walks with his accustomed vigour. What gaiety smiles in his countenance! the liveliest sallies of wit flow unnumbered from his lips; he is another being—a new man; but coffee alone has produced this regeneration. The late Doctor Gastaldi, who was an excellent table companion, used to say that he should have died ten times of indigestion if he had not accustomed himself to take coffee after dinner.

Would you then sleep tranquilly after your meal, and never fear those dreams which are so fatal to gourmands, quaff your coffee; it will fall like dew upon your lips, and sweetly temper with all those juices which oppress your exhausted stomach. If you can, drink your coffee without sugar, for then it preserves its natural flavour, and is much more efficacious than when mixed with other ingredients. Laugh at the doctors who tell you that hot coffee irritates the stomach and injures the nerves; tell them that Voltaire, Fontenelle, Stacey, and Fourcroy, who were great coffee-drinkers, lived to a good old age.

The brochure, for such it is, is wound up with “the natural history of coffee,” and an appendix of “English receipts,” &c.

PERILS OF THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE IN SOUTH AMERICA

A work of extraordinary and soul-stirring interest has lately appeared on the Revolutions of South America. It is entitled “Memoirs of General Miller, in the Service of the Republic of Peru,” and is compiled from private letters, journals, and recollections, by the brother of the general. From this portion of the work we gather that William Miller, the companion in arms of San Martin and Bolivar, was born in Kent, in 1795. He served with the British army in Spain and America, from 1811 till the peace of 1815. In 1816 and 1817, he devoted some attention to mercantile affairs; but being of an ardent spirit he finally resolved to engage as a candidate for military honour in the struggle in South America. Colombia was overrun with adventurers; and Miller directed his course to the river La Plata. He left England in August, 1817, when he was under twenty-two years of age, and landed at Buenos Ayres in the September following. In a month after, he received a captain’s commission in the army of the Andes. In the beginning of 1818, captain Miller set out for the army of San Martin, and crossed the Andes by the pass of Uspallata. He soon joined his companions in arms. His first military enterprise was unsuccessful, but a notice of it will give our readers a faint idea of the perils of a campaign in the mountainous regions of South America. Miller, it appears, was on his march towards the capital of Chile; the artillery consisted of ten six-pounders, to this branch of the service his attention was, of course, devoted. The incident occurred in crossing the Maypo, a torrent which rushes from a gorge of the Andes.

The only bridge over it is made of what may be called hide cables. It is about two hundred and fifty feet long, and just wide enough to admit a carriage. It is upon the principle of suspension, and constructed where the banks of the river are so bold as to furnish natural piers. The figure of the bridge is nearly that of an inverted arch. Formed of elastic materials, it rocks a good deal when passengers go over it. The infantry, however, passed upon the present occasion without the smallest difficulty. The cavalry also passed without any accident by going a few at a time, and each man leading his horse. When the artillery came up, doubts were entertained of the possibility of getting it over. The general had placed himself on an eminence, to see his army file to the opposite side of the river. A consultation was held upon the practicability of passing the guns. Captain Miller volunteered to conduct the first gun. The limber was taken off, and drag ropes were fastened to the washers, to prevent the gun from descending too rapidly. The trail, carried foremost, was held up by two gunners, but, notwithstanding every precaution, the bridge swung from side to side, and the carriage acquired so much velocity, that the gunners who held up the trail, assisted by captain Miller, lost their equilibrium, and the gun upset. The carriage, becoming entangled in the thong balustrade, was prevented from falling into the river, but the platform of the bridge acquired an inclination almost perpendicular, and all upon it were obliged to cling to whatever they could catch hold of to save themselves from being precipitated into the torrent, which rolled and foamed sixty feet below. For some little time none dared go to the relief of the party thus suspended, because it was supposed that the bridge would snap asunder, and it was expected that in a few moments all would drop into the abyss beneath. As nothing material gave way, the alarm on shore subsided, and two or three men ventured on the bridge to give assistance. The gun was dismounted with great difficulty, the carriage dismantled, and conveyed piecemeal to the opposite shore. The rest of the artillery then made a detour, and crossed at a ford four or five leagues lower down the river.

Miller soon became advanced to the rank of brevet-major: in November, 1818, he joined Lord Cochrane, who took the command of the naval forces of Chile, and was accompanied by major Miller, as commander of the marines, in nearly all his expeditions. Lord Cochrane failing in his first attack on Callao, resolved to fit out fire-ships, and a laboratory was accordingly formed under the superintendance of major Miller. Here our gallant adventurer was nearly destroyed by an accidental explosion; and in an attack shortly afterwards at Pisco, he was desperately wounded, so that his life was for seventeen days despaired of.

In the capture of Valdivia, one of the bravest exploits of modern warfare, Miller acted a distinguished part, and narrowly escaped destruction, a ball passing through his hat, and grazing the crown of his head. The narrative of this glorious scene is unfortunately too long for transference to our columns, and the omission of any of the details would interfere with its glowing interest.

Miller was again wounded in an unsuccessful attempt, under Lord Cochrane, to capture the Island of Chiloe. In June, 1820, he was made lieutenant-colonel of the eighth battalion of Buenos Ayres, and in the August following, he embarked for Valparaiso, with his battalion, forming a part of the liberating army of Peru. They made the passage to Pisco, a distance of 1,500 miles, in fifteen days; and from this point commenced that series of sanguinary conflicts which terminated, in five years, in the complete liberation of the country of the Incas. During the land operations was Lord Cochrane’s triumphant capture of the Spanish frigate, the Esmeralda, in the fort of Callao, which is briefly but vividly told.

Early in 1821, lieutenant-colonel Miller abandoned Pasco, and re-embarked for the fort of Arica; and after a hair-breadth escape, landed ten leagues north of that point. The colonel now advanced with his little army of 400 men into the country, where he routed the royalist troops, and in a fortnight killed or captured more than 600 Spaniards. In 1822, he was promoted to the rank of colonel, and the civil and military government of an extensive district in Peru; in which year also he was engaged in several important battles. In the beginning of 1823, with only a company of caçadores, he harassed the royalists for several months; and so alarmed the enemy by the rapidity of his movements, that he often passed the hostile division, of a thousand men, without their daring to attack him. Of the country in which these operations were carried on, the general gives a frightful picture.