полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 38, July 20, 1850

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 38, July 20, 1850

NOTES

WHAT IS THE MEANING OF "DELIGHTED," AS SOMETIMES USED BY SHAKSPEARE

I wish to call attention to the peculiar use of a word, or rather to a peculiar word, in Shakspeare, which I do not recollect to have met with in any other writer. I say a "peculiar word," because, although the verb To delight is well known, and of general use, the word, the same in form, to which I refer, is not only of different meaning, but, as I conceive, of distinct derivation the non-recognition of which has led to a misconception of the meaning of one of the finest passages in Shakspeare. The first passage in which it occurs, that I shall quote, is the well known one from Measure for Measure:

"Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;To lie in cold obstruction, and to rot,This sensible warm motion to becomeA kneaded clod; and the delighted spiritTo bathe in fiery floods, or to resideIn thrilling regions of thick-ribbed ice;To be imprison'd in the viewless windsAnd blown with restless violence round aboutThe pendant world." Act iii. Sc. 1.Now, if we examine the construction of this passage, we shall find that it appears to have been the object of the writer to separate, and place in juxtaposition with each other, the conditions of the body and the spirit, each being imagined under circumstances to excite repulsion or terror in a sentient being. The mind sees the former lying in "cold obstruction," rotting, changed from a "sensible warm motion" to a "kneaded clod," every circumstance leaving the impression of dull, dead weight, deprived of force and motion. The spirit, on the other hand, is imagined under circumstances that give the most vivid picture conceivable of utter powerlessness:

"Imprison'd in the viewless winds,And blown with restless violence round aboutThe pendant world."To call the spirit here "delighted," in our sense of the term, would be absurd; and no explanation of the passage in this sense, however ingenious, is intelligible. That it is intended to represent the spirit simply as lightened, made light, relieved from the weight of matter, I am convinced, and this is my view of the meaning of the word in the present instance.

Delight is naturally formed by the participle de and light, to make light, in the same way as "debase," to make base, "defile," to make foul. The analogy is not quite so perfect in such words as "define," "defile" (file), "deliver," "depart," &c.; yet they all may be considered of the same class. The last of these is used with us only in the sense of to go away; in Shakspeare's time (and Shakspeare so uses it) it meant also to part, or part with. A correspondent of Mr. Knight's suggests for the word delight in this passage, also, a new derivation; using de as a negation, and light (lux), delighted, removed from the regions of light. This is impossible; if we look at the context we shall see that it not only contemplated no such thing, but that it is distinctly opposed to it.

I am less inclined to entertain any doubt of the view I have taken being correct, from the confirmation it receives in another passage of Shakspeare, which runs as follows:

"If virtue no delighted beauty lack,Your son-in-law shows far more fair than black."Othello, Act i. Sc. 3.

Passing by the cool impertinence of one editor, who asserts that Shakspeare frequently used the past for the present participle, and the almost equally cool correction of another, who places the explanatory note "*delightful" at the bottom of the page, I will merely remark that the two latest editors of Shakspeare, having apparently nothing to say on the subject, have very wisely said nothing. Yet, as we understand the term "delighted," the passage surely needs explanation. We cannot suppose that Shakspeare used epithets so weakening as "delighting" or "delightful." The meaning of the passage would appear to be this: If virtue be not wanting in beauty—such beauty as can belong to virtue, not physical, but of a higher kind, and freed from all material elements—then your son-in-law, black though he is, shows far more fair than black, possessing, in fact, this abstract kind of beauty to that degree that his colour is forgotten. In short, "delighted" here seems to mean, lightened of all that is gross or unessential.

There is yet another instance in Cymbeline, which seems to bear a similar construction:

"Whom best I love, I cross: to make my giftsThe more delay'd, delighted."Act v. Sc. 4.

That is, "the more delighted;" the longer held back, the better worth having; lightened of whatever might detract from their value, that is, refined or purified. In making the remark here, that "delighted" refers not to the recipient nor to the giver, but to the gifts, I pass by the nonsense that the greatest master of the English language did not heed the distinction between the past and the present participles, as not worth a second thought.

The word appears to have had a distinct value of its own, and is not to be explained by any other single word. If this be so, it could hardly have been coined by Shakspeare. Though, possibly, it may never have been much used, perhaps some of your correspondents may be able to furnish other instances from other writers.

SAMUEL HICKSON.St. John's Wood.

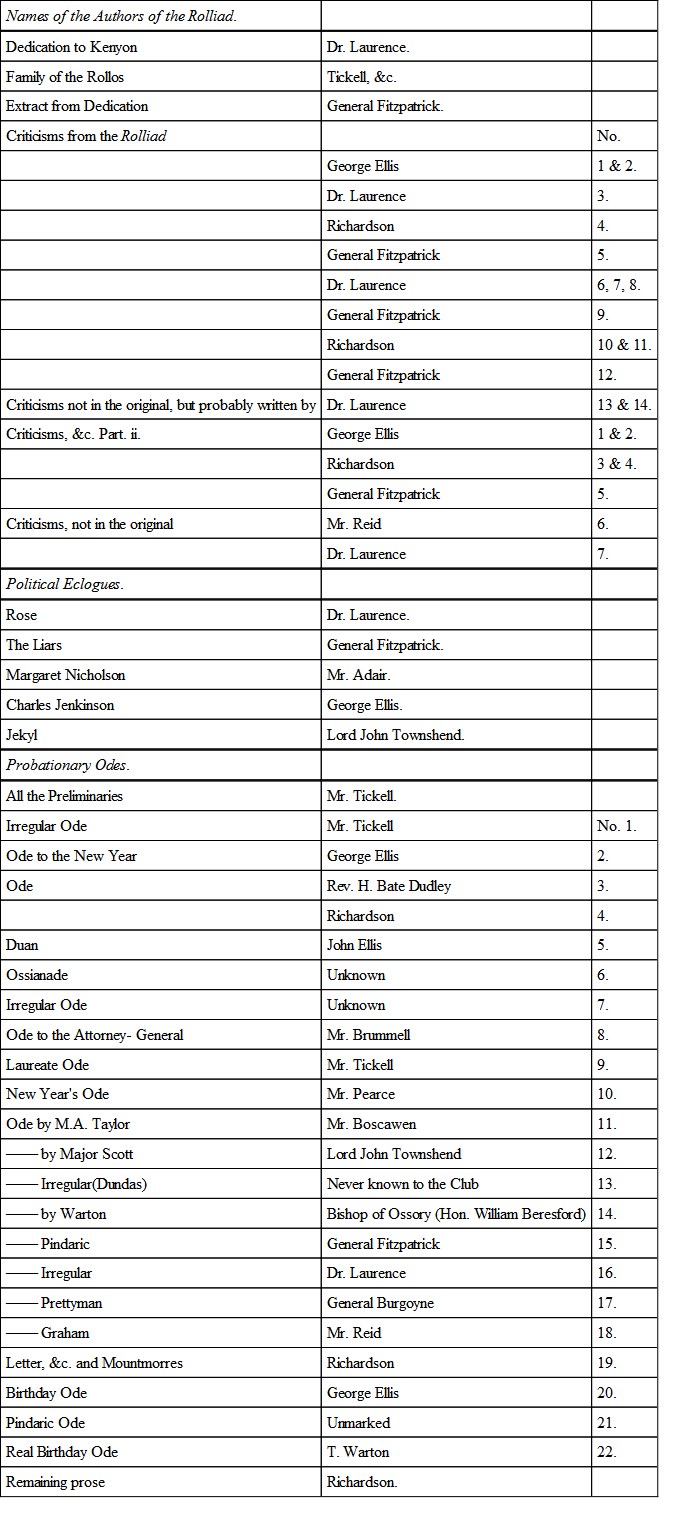

AUTHORS OF "THE ROLLIAD."

The subjoined list of the authors of The Rolliad, though less complete than I could have wished, is, I believe, substantially correct, and may, therefore, be acceptable to your readers. The names were transcribed by me from a copy of the ninth edition of The Rolliad (1791), still in the library at Sunninghill Park, in which they had been recorded on the first page of the respective papers.

There seems to be no doubt that they were originally communicated by Mr. George Ellis, who has always been considered as one of the most talented contributors to The Rolliad. He also resided for many years at Sunninghill, and was in habits of intimacy with the owners of the Park. Your correspondent C. (Vol. ii., p. 43.) may remark that Lord John Townshend's name occurs only twice in my list; but his Lordship may have written some of the papers which are not in the Sunninghill volume, as they appeared only in the editions of the work printed subsequently to 1791, and are designated as Political Miscellanies.

I am not certain whether Mr. Adair, to whom "Margaret Nicholson," one of the happiest of the Political Eclogues, is attributed, is the present Sir Robert Adair. If so, as the only survivor amongst his literary colleagues, he might furnish some interesting particulars respecting the remarkable work to which I have called your attention.

BRAYBROOKE.Audley End, July, 1850.

NOTES ON MILTON

(Continued from Vol. ii., p. 53.)Il Penseroso.

On l. 8 (G.):—

"Fantastic swarms of dreams there hover'd,Green, red, and yellow, tawney, black, and blue;They make no noise, but right resemble mayTh' unnumber'd moats that in the sun-beams play."Sylvester's Du Bartas.

Cælia, in Beaumont and Fletcher's Humorous Lieutenant, says,—

"My maidenhead to a mote in the sun, he's jealous."Act iv. Sc. 8.

On l. 35. (G.) Mr. Warton might have found a happier illustration of his argument in Ben Jonson's Every Man in his Humour, Act i. Sc. 3.:—

"Too conceal such real ornaments as these, and shadowtheir glory, as a milliner's wife does her wroughtstomacher, with a smoaky lawn, or a black cyprus."—Whalley's edit. vol. i. p. 33.

On l. 39. (G.) The origin of this uncommon use of the word "commerce" is from Donne:—

"If this commerce 'twixt heaven and earth were notembarred."—Poems, p. 249. Ed. 4to. 1633.

On l. 43. (G.):—

"That sallow-faced, sad, stooping nymph, whose eyeStill on the ground is fixed steadfastly."Sylvester's Du Bartas

On l. 52. (G.):—

"Mounted aloft on Contemplation's wings."G. Wither, P. 1. vol. i. Ed. 1633.

Drummond has given "golden wings" to Fame.

On l. 88. (G.):—

Hermes Trismegistus.On l. 100. (G.):—

"Tyrants' bloody gestsOf Thebes, Mycenæ, or proud Ilion."Sylvester's Du Bartas.

Arcades.

On l. 23. (G.):—

"And without respect of odds,Vye renown with Demy-gods."Wither's Mistresse of Philarete, Sig. E. 5. Ed. 1633.

On l. 27. (G.):—

"But yet, whate'er he do or can devise,Disguised glory shineth in his eyes."Sylvester's Du Bartas.

On l. 46. (G.):—

"An eastern wind commix'd with noisome airs,Shall blast the plants and the young sapplings."Span. Trag. Old Plays, vol. iii. p. 222.

On l. 65. (G.) Compare Drunmond—speech of Endymion before Charles:—

"To tell by me, their herald, coming things,And what each Fate to her stern distaff sings," &c.On l. 84. (M.):—

"And with his beams enamel'd every greene."Fairfax's Tasso, b. i. st. 35.

On l. 97. (G.):—

"Those brooks with lilies bravely deck't."Drayton, 1447.

On l. 106. (G.):—

"Pan entertains, this coming night,His paramour, the Syrinx bright."Fletcher's Faithful Shepherdess, Act i.

J.F.M.DERIVATION OF EASTER

Southey, in his Book of the Church, derives our word Easter from a Saxon source:—

"The worship," he says, "of the goddess Eostre or Eastre, which may probably be traced to the Astarte of the Phoenicians, is retained among us in the word Easter; her annual festival having been superseded by that sacred day."

Should he not rather have given a British origin to the name of our Christian holy day? Southey acknowledges that the "heathenism which the Saxons introduced, bears no [very little?] affinity either to that of the Britons or the Romans;" yet it is certain that the Britons worshipped Baal and Ashtaroth, a relic of whose worship appears to be still retained in Cornwall to this day. The Druids, as Southey tells us, "made the people pass through the fire in honour of Baal." But the festival in honour of Baal appears to have been in the autumn: for

"They made the people," he informs us, "at the beginning of winter, extinguish all their fires on one day and kindle them again from the sacred fire of the Druids, which would make the house fortunate for the ensuing year; and, if any man came who had not paid his yearly dues, [Easter offerings, &c., date back as far as this!] they refused to give him a spark, neither durst any of his neighbours relieve him, nor might he himself procure fire by any other means, so that he and his family were deprived of it till he had discharged the uttermost of his debt."

The Druidical fires kindled in the spring of the year, on the other hand, would appear to be those in honour of Ashtaroth, or Astarte, from whom the British Christians may naturally enough have derived the name of Easter for their corresponding season. We might go even further than this, and say that the young ladies who are reported still to take the chief part in keeping up the Druidical festivities in Cornwall, very happily represent the ancient Estal (or Vestal) virgins.

"In times of Paganism," says O'Halloran, "we find in Ireland females devoted to celibacy. There was in Tara a royal foundation of this kind, wherein none were admitted but virgins of the noblest blood. It was called Cluain-Feart, or the place of retirement till death," &c … "The duty of these virgins was to keep up the fires of Bel, or the sun, and of Sambain, or the moon, which customs they borrowed from their Phoenician ancestors. They both [i.e. the Irish and the Phoenicians] adored Bel, or the sun, the moon, and the stars. The 'house of Rimmon' which the Phoenicians worshipped in, like our temples of Fleachta in Meath, was sacred to the moon. The word 'Rimmon' has by no means been understood by the different commentators; and yet, by recurring to the Irish (a branch of the Phoenician) it becomes very intelligible; for 'Re' is Irish for the moon, and 'Muadh' signifies an image, and the compound word 'Reamhan,' signifies prognosticating by the appearance of the moon. It appears by the life of our great S. Columba, that the Druid temples were here decorated with figures of the sun, the moon, and stars. The Phoenicians, under the name of Bel-Samen, adored the Supreme; and it is pretty remarkable, that to this very day, to wish a friend every happiness this life can afford, we say in Irish, 'The blessings of Samen and Bel be with you!' that is, of the seasons; Bel signifying the sun, and Samhain the moon."

—(See O'Halloran's Hist. of Ireland, vol. i. P. 47.)

J. SANSOM.FOLK LORE

Presages of Death.—The Note by Mr. C. FORBES (Vol. ii., p. 84.) on "High Spirits considered a Presage of impending Calamity or Death," reminded me of a collection of authorities I once made, for academical purposes, of a somewhat analogous bearing,—I mean the ancient belief in the existence of a power of prophecy at that period which immediately precedes dissolution.

The most ancient, as well as the most striking instance, is recorded in the forty-ninth chapter of Genesis:—

"And Jacob called his sons and said, Gather yourselves together that I may tell you that which shall befall you in the last days.... And when Jacob had made an end of commanding his sons, he gathered up his feet into his bed, and yielded up the ghost, and was gathered unto his people."

Homer affords two instances of a similar kind: thus, Patroclus prophesies the death of Hector (Il. [Greek: p] 852.)1:—

[Greek: "Ou thaen oud autos daeron beae alla toi aedaeAgchi parestaeke Thanatos kai Moira krataiae,Chersi dament Achilaeos amnmonos Aiakidao."]2Again, Hector in his turn prophesies the death of Achilles by the hand of Paris (Il. [Greek: ch.] 358.):—

[Greek: "Phrazeo nun, mae toi ti theon maenima genomaiAemati to ote ken se Pharis kai phoibus Apollon,Esthlon eont, olesosin eni Skaiaesi pulaesin."]3This was not merely a poetical fancy, or a superstitious faith of the ignorant, for we find it laid down as a great physical truth by the greatest of the Greek philosophers, the divine Socrates:—

[Greek: "To de dae meta touto epithumo humin chraesmodaesai, o katapsaephisamenoi mou kai gar eimi aedae entautha en o malist anthropoi chraesmodousin hotan mellosin apothaneisthai."]4

In Xenophon, also, the same idea is expressed, and, if possible, in language still more definite and precise:—

[Greek: "Hae de tou anthropou psuchae tote daepou theiotatae kataphainetai, kai tote ti ton mellonton proora."]5

Diodorus Siculus, again, has produced great authorities on this subject:—

[Greek: "Puthagoras ho Samios, kai tines heteroi ton palaion phusikon, apephaenanto tas psuchas ton anthropon uparchein athanatous, akolouthos de to dogmati touto kai progignoskein autas ta mellonta, kath hon an kairon en tae teleutae ton apo tou somatos chorismon poiontai."]6

From the ancient writers I yet wish to add one more authority; and I do so especially, because the doctrine of the Stagirite is therein recorded. Sextus Empiricus writes,—

[Greek: "Hae psuchae, phaesin Aristotelaes, promanteuetai kai proagoreuei ta mellonta—en to kata thanaton chorizesthai ton somaton."]7

Without encroaching further upon the space of this periodical by multiplying evidence corroborative of the same fact, I will content myself by drawing the attention of the reader to our own great poet and philosopher, Shakspeare, whose subtle genius and intuitive knowledge of human nature render his opinions on all such subjects of peculiar value. Thus in Richard II., Act ii. sc. 1., the dying Gaunt, alluding to his nephew, the young and self-willed king, exclaims,—

"Methinks I am a prophet new inspired;And thus, expiring, do foretel of him."Again, in Henry IV., Part I., Act v. sc. 4., the brave Percy, when in the agonies of death, conveys the same idea in the following words:—

"O, I could prophesy,But that the earthy and cold hand of deathLies on my tongue."Reckoning, therefore, from the time of Jacob, this belief, whether with or without foundation, has been maintained upwards of 3500 years. It was grounded on the assumed fact, that the soul became divine in the same ratio as its connection with the body was loosened or destroyed. In sleep, the unity is weakened but not ended: hence, in sleep, the material being dead, the immaterial, or divine principle, wanders unguided, like a gentle breeze over the unconscious strings of an Æolian harp; and according to the health or disease of the body are pleasing visions or horrid phantoms (ægri somnia, as Horace) present to the mind of the sleeper. Before death, the soul, or immaterial principle, is, as it were, on the confines of two worlds, and may possess at the same moment a power which is both prospective and retrospective. At that time its connection with the body being merely nominal, it partakes of that perfectly pure, ethereal, and exalted nature (quod multo magis faciet post mortem quum omnino corpore excesserit) which is designed for it hereafter.

As the question is an interesting one, I conclude by asking, through the medium of the "NOTES AND QUERIES," if a belief in this power of prophesy before death be known to exist at the present day?

AUGUSTUS GUEST.London, July 8.

Divination at Marriages.—The following practices are very prevalent at marriages in these districts; and as I do not find them noticed by Brand in the last edition of his Popular Antiquities, they may perhaps be thought worthy a place in the "NOTES AND QUERIES."

1. Put a wedding ring into the posset, and after serving it out, the unmarried person whose cup contains the ring will be the first of the company to be married.

2. Make a common flat cake of flour, water, currants, &c., and put therein a wedding ring and a sixpence. When the company is about to retire on the wedding-day, the cake must be broken and distributed amongst the unmarried females. She who gets the ring in her portion of the cake will shortly be married, and the one who gets the sixpence will die an old maid.

T.T.W.Burnley, July 9. 1850.

FRANCIS LENTON THE POET

In a MS. obituary of the seventeenth century, preserved at Staunton Hall, Leicestershire, I found the following:—

"May 12. 1642. This day died Francis Lenton, of Lincoln's Inn, Gent."

This entry undoubtedly relates to the author of three very rare poetical tracts: 1. The Young Gallant's Whirligigg, 1629; 2. The Innes of Court, 1634; 3. Great Brittain's Beauties, 1638. In the dedication to Sir Julius Cæsar, prefixed to the first-named work, the writer speaks of having "once belonged to the Innes of Court," and says he was "no usuall poetizer, but, to barre idlenesse, imployed that little talent the Muses conferr'd upon him in this little tract." Sir Egerton Brydges supposed the copy of The Young Gallant's Whirligigg preserved in the library of Sion College to be unique; but this is not the case, as the writer knows of two others,—one at Staunton Hall, and another at Tixall Priory in Staffordshire. It has been reprinted by Mr. Halliwell at the end of a volume containing The Marriage of Wit and Wisdom, published by the Shakspeare Society. In his prefatory remarks that gentleman says,

"Besides his printed works, Lenton wrote the Poetical History of Queene Hester, with the translation of the 83rd Psalm, reflecting upon the present times. MS. dated 1649."

This date must be incorrect, if our entry in the Staunton obituary relates to the same person; and there is every reason to suppose that it does. The autograph MS. of Lenton occurred in Heber's sale (Part xi. No. 724.), and is thus described:

Hadassiah, or the History of Queen Hester, sung in a sacred and serious poeme, and divided into ten chapters, by F. Lenton, the Queen's Majesties Poet, 1638.

This is undoubtedly the correct date, as it is in the handwriting of the author. Query. What is the meaning of Lenton's title, "the Queen's Majesties Poet"?

Edward F. Rimbault.Minor Notes

Lilburn or Prynne?—I am anxious to suggest in "Notes and Queries" whether a character in the Second Canto of Part iii. of Hudibras (line 421), beginning,

"To match this saint, there was another,As busy and perverse a brother,An haberdasher of small wares,In politics and state affairs,"Has not been wrongly given by Dr. Grey to Lilburn, and whether Prynne is not rather the person described. Dr. Grey admits in his note that the application of the passage to Lilburn involves an anachronism, Lilburn having died in 1657, and this passage being a description of one among

"The quacks of government who sate"to consult for the Restoration, when they saw ruin impending.

CH.Peep of Day.—Jacob Grimm, in his Deutsche Mythologie, p. 428., ed. 1., remarks that the ideas of light and sound are sometimes confounded; and in support of his observation he quotes passages of Danish and German poets in which the sun and moon are said to pipe (pfeifen). In further illustration of this usage, he also cites the words "the sun began to peep," from a Scotch ballad in Scott's Border Minstrelsy, vol. ii. p. 430. In p. 431. he explains the words "par son l'aube," which occur in old French poets, by "per sonitum auroræ;" and compares the English expression, "the peep of day."

The Latin pipio or pipo, whence the Italian pipare, and the French pépier, is the ultimate origin of the verb to peep; which, in old English, bore the sense of chirping, and is so used in the authorised version of Isaiah, viii. 19., x. 14. Halliwell, in his Archaic Dictionary, explains "peep" as "a flock of chickens," but cites no example. To peep, however, in the sense of taking a rapid look at anything through a small aperture, is an old use of the word, as is proved by the expression Peeping Tom of Coventry. As so used, it corresponds with the German gucken. Mr. Richardson remarks that this meaning was probably suggested by the young chick looking out of the half-broken shell. It is quite certain that the "peep of day" has nothing to do with sound; but expresses the first appearance of the sun, as he just looks over the eastern hills.

L.Martinet.—Will the following passage throw any light on the origin of the word Martinet?

Une discipline, devenue encore plus exacte, avait mis dans l'armée un nouvel ordre. Il n'y avait point encore d'inspecteurs de cavalerie et d'infanterie, comme nous en avons vu depuis, mais deux hommes uniques chacun dans leur genre en fesaient les fonctions. Martinet mettait alors l'infanterie sur le pied de discipline où elle est aujourd'hui. Le Chevalier de Fourilles fesait la même change dans la cavalerie. Il y avait un an que Martinet avait mis la baionnette en usage dans quelque régimens, &c.—Voltaire, Siècle de Louis XIV. c. 10.

C. Forbes.July 2.

Guy's Porridge Pot.—In the porter's lodge at Warwick Castle are preserved some enormous pieces of armour, which, according to tradition, were worn by the famous champion "Guy, Earl of Warwick;" and in addition (with other marvellous curiosities) is also exhibited Guy's porridge pot, of bell metal, said to weigh 300 lbs., and to contain 120 gallons. There is also a flesh-fork to ring it.

Mr. Nichols, in his History of Leicestershire, Part ii. vol. iii., remarks,

"A turnpike road from Ashby to Whitwick, passes through Talbot Lane. Of this lane and the famous large pot at Warwick Castle, we have an old traditionary couplet: