полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 541, April 7, 1832

The lights of Love among the Roses are vivid and beautiful: the whole composition will be recollected as of a charming character.

By the way, persons unpractised in the art of painting on glass, or in transparent enamel, have but a slender idea of its difficulties. Crown-glass is preferred for its greater purity. The artist has not only to paint the picture, but to fire it in a kiln, with the most scrupulous attention to produce the requisite effects, and the uncertainty of this branch of the art is frequently a sad trial of patience. Hence, the firing or vitrification of the colours is of paramount importance, and the art thus becomes a two-fold trial of skill. Its cost is, however, only consistent with its brilliant effect.

NOTES OF A READER

TEA

What can we do with this pamphlet?—British Relations with the Chinese Empire—Comparative Statement of the English and American Trade with India and Canton. What a book for a tea-drinking old lady, or Dr. Johnson, of tea-loving notoriety, with his thirteen cups to the dozen.

"The writer has passed the last eleven years of his life in visiting every quarter of the globe, and the colonial possessions of Great Britain, in order to acquire an intimate knowledge of her commercial affairs, for political purposes." The reader will, perhaps, say this pamphlet is purely political, and what have you to do with it? But it is not so: there are facts in these pages which interest every one and come home to every man's mouth: the political purpose is to us like chaff; and these facts like grains of wheat, so we will even pick a few. Meanwhile, the whole pamphlet must be important to all, as to ourselves parts are interesting: it represents the literature of the tea trade, and, best of all, the profitable literature of L.s.d. It is written in a patriotic spirit; witness this extract from the preface: "To a commercial union of wealth, and a co-operation of talent and patriotism, a small island in the Western Atlantic is indebted for the acquisition of one of the most splendid empires that ever was subjected to the dominion of man, and also for the rise and progress of an extraordinary commerce with a people inhabiting a distant hemisphere, and heretofore shut out from all intercourse with the majority of the human race;—a commerce equal in extent to 10,000,000l. annually, and involving property to the amount of ten times that sum."

Our facts must stand isolated, since to weave them into an argument would be altogether foreign to our purpose.

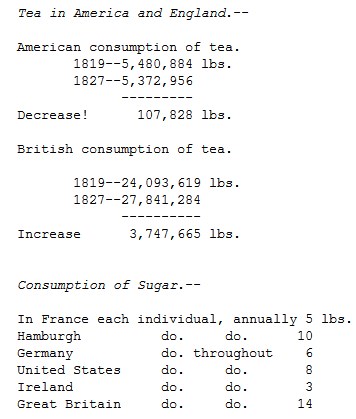

East India Company.—Although the East India Company can alone import tea, they cannot choose their own time of sale; they are compelled to put up the tea at an advance of one penny (they do at one farthing) per lb.; they are obliged to have twelve months' stock in hand; and while the tea in America has increased in price and diminished in consumption, the very reverse has taken place in England, as official returns prove!

China presents the very remarkable spectacle of a civilization entirely political, whose principal aim has constantly been to draw closer the bonds which unite the society it formed, and to merge, by its laws, the interest of the individual in that of the public; an empire possessing an active, skilful, and contented population of 155,000,000 souls, who are spread over 1,372,450 square miles of the fairest and, probably, earliest inhabited region of the globe—that maintains a standing army of 1,182,000 men, and levies a revenue of only 11,649,912l. sterling—an empire that has preserved the records of its dominion and the integrity of its name from a period of three thousand years antecedent to our era, while the most powerful monarchies of remote or modern ages have dwindled into nothingness, or been borne towards the ocean of eternity, by the swiftly destructive gulf of time,—an empire whose people have materially contributed to advance the civilization of Europe and America, by the discovery of the most useful arts and sciences, such as writing, 3 astronomy, the mariner's compass, gunpowder, sugar, silk, porcelain, the smelting and combination of metals,—and, in fine, enjoying within its own territories all the necessaries and conveniencies, and most of the luxuries of life; standing, as it proudly asserts, in no need of intercourse with other countries, 4 which it is its studied policy to prohibit, 5 openly and arrogantly proclaims its total independence of every nation in the world!

Origin of the Tea Trade of the East India Company.—In 1668, the East India Company ordered "one hundred pounds weight of goode tey" to be sent home on speculation. A taste for the Chinese herb was created and carefully fostered; the invoice was increased from year to year, until it now amounts to 30,000,000 pounds weight (notwithstanding the excessive duty of 100 per cent, and the onerous restrictions of the commutation act, since 1784), yielding an annual revenue to government, on a luxury of life, of about 3,300,000l. sterling, with scarcely any trouble or expense in the collecting;—employing 35,000 tons of the finest shipping,—requiring annually nearly 1,000,000l. sterling worth of cotton, woollen, and iron manufactures, and affording employment to a numerous class of society, for the wholesale and retail dealing in a leaf collected on the mountains of a distant continent!

To enable them the better to prosecute this valuable commerce, the East India Company sought and obtained permission to build a factory at Canton, where their agents were permitted to reside six months in the year—a favour specifically accorded as a matter of compassion to foreigners, who are carefully debarred all intercourse with the interior of the country; a dread being entertained that the introduction of Europeans to settle in China, would lead (according also to ancient prophecy) to the total subversion of the empire.

Other brunches of trade were subsequently added to that of tea. In 1773, the East India Company made a small adventure of opium 6 from Bengal to Canton; and the consumption of opium increased as rapidly among the Chinese as tea did among the English, until it now yields (although a contraband trade) 14,000,000 Spanish dollars annually, 7 and pays a revenue to the Indian Government of 1,800,000l. sterling. Raw cotton forms another extensive article of export to China; it is in general a less profitable remittance than bills of exchange, but the exportation is encouraged for the benefit of the Indian territories.

Character of the Chinese.—The Chinese are a haughty and independent race of people, whose commercial policy it is to prohibit, as much as possible, every species of manufactures 8 and bullion; and encourage the importation of food, and raw produce; holding themselves aloof from Europeans, and particularly jealous of Great Britain, on account of the proximity of her Indian empire; exacting upwards of 1,000l. in fees and port dues 9 on each foreign vessel that enters Canton, the only harbour to which they are admitted, 10 imposing severe sea and inland customs and regulations regarding woollen and other manufactures, entirely interdicting some branches of trade, and permitting all by sufferance, or as a matter of favour rather than from necessity, or by right.

Tea in Ireland.—In Ireland, the consumption of tea in the year 1828, was 1,300,000 lbs. less than in 1827; and although the population of Ireland has rapidly increased, indeed, nearly doubled itself, since the commencement of the present century, yet the quantity of tea imported into that country is 400,000 lbs. less in 1828, than it was in 1800!

Fourteen pounds of sugar per annum, will afford but little more than half an ounce a day to each individual; a quantity, which it is well known the youngest child will consume, and yet a large portion of the sugar entered for home consumption, is used in breweries, and distilleries, so that it is even doubtful, whether the personal direct consumption of tea or sugar be the greatest; notwithstanding the latter may be had in such great abundance and in every country within the tropics.

Price of Tea in China.—Bohea, which cannot be purchased in China at less than eight-pence half-penny, may be obtained at Antwerp for 7-3/4d.; in France for 6-1/2d.; and at Hamburg for 5d.! Congou, of which the Canton price is from 11d. to 1s. per lb., may be bought in France at 10-1/2d., and at Hamburg from 8-1/4d. to 10-1/4d.! Canton price for Hyson, 1s. 9-3/4d.; French price 1s. 8-1/2d. Young Hyson costs in Canton about 1s. 8-1/2d. per lb., and only one half that sum at Hamburg!! The Chinese cannot afford to sell Twankay at less than 11d. per lb.; but the American speculators enable the good people of Hamburg to drink it at seven-pence farthing! Souchong, a good quality tea, sells at Hamburg for five-pence per lb., which is the same price as the vilest Bohea costs in the Hamburg market, and is only one-half the price of Bohea in Canton.

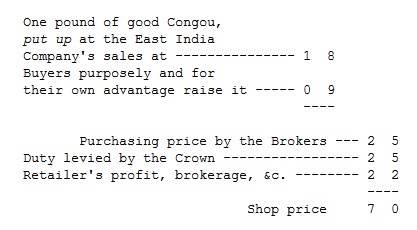

Cost of a pound of Seven Shilling Tea.—Take a pound of Congou for instance, according to the evidence of Mr. Mills, a tea broker, before the House of Lords:

Thus it will be seen, the tea that the Company offers for sale to the consumer at 1s. 8d., or at the utmost say 2s., is enhanced to 7s. before it finds its way to the drinker's breakfast table.

Coffee-Shops.—There are 3,000 coffee shops in London, in which are daily consumed 2,000 lbs. of tea and 15,000 lbs. of coffee. The consumption of coffee in these establishments has increased as follows:—In 1829, 1,978,600 lbs. In 1830, 2,251,300 lbs. In 1831, 2,899,870. Of tea the increase has only been, during the same periods, 239,700 lbs.—249,400 lbs.—263,000 lbs.

FOX-HUNTING

The following are the items of expenses, laid down by Colonel Cooke, in his "Observations on Fox-hunting," published a few years since. The calculation supposes a four-times-a-week country; but it is generally below the mark; we should say, at least one-half:—

Of course, countries vary much in expense from local circumstance; such as the necessity for change of kennels, hounds sleeping out, &c.&c. In those which are called hollow countries, consequently abounding in earths, the expense of earth-stopping often amounts to 200l. per annum, and Northamptonshire is of this class. In others, a great part of the foxes are what is termed stub-bred (bred above ground), which circumstance reduces the amount of this item.—Quarterly Review.

THE GATHERER

Curious Epitaph.—In Nichols's History of Leicestershire, is inserted the following epitaph, to the memory of Theophilus Cave, who was buried in the chancel of the church of Barrow on Soar:

"Here in this Grave there lies a Cave;We call a Cave a Grave;If Cave be Grave, and Grave be Cave,Then reader, judge, I crave,Whether doth Cave here lye in Grave,Or Grave here lye in Cave:If Grave in Cave here bury'd lye,Then Grave, where is thy victory?Goe, reader, and report here lyes a CaveWho conquers death, and buryes his own Cave."P.T.W.

Equality.—All men would necessarily have been equal, had they been without wants; it is the misery attached to our species, which places one man in subjection to another: Inequality is not the real grievance, but dependence. It is of little consequence for one man to be called his highness, and another his holiness; but it is hard for one to be the servant of another.—Voltaire.

The famous Duke of Cumberland showed more cleverness as a boy, than he ever did as a general. Having displeased his mother one day, she sent him to his chamber, and when he appeared again, she asked him what he had been doing. "Reading," replied the boy.—"Reading what?"—"The Scriptures."—"What part of the Scriptures?"—"That part where it is written, 'Woman! what hast thou to do with me?'" After the loss of a battle, an English prisoner observing to a French officer, that they might have taken the duke himself prisoner; "Yes," replied the Frenchman, "but we took care not to do that—he is of far more use to us at the head of your army."—Georgian Era.

The letter Y.—Pythagoras used the Y as a symbol of human life. "Remember (says he) that the paths of virtue and of vice resemble the letter Y. The foot representing infancy, and the forked top the two paths of vice and virtue, one or the other of which people are to enter upon, after attaining to the age of discretion."

P.T.W.

Royal Combat.—Near the city of Gloucester, on the Severn, the river dividing, forms a small island called Alney, which is famous for a royal combat fought on it, between Edmund Ironside and Canute the Dane, to decide the fate of the kingdom, in sight of both their armies. Canute was wounded, when he proposed an amicable division, and accordingly he obtained the northern part; the southern falling to Edmund.

E.F.

Effect of Music.—A Scotch bag-piper traversing the mountains of Ulster, in Ireland, was one evening encountered by a starved Irish wolf. In his distress the poor man could think of nothing better than to open his wallet, and try the effects of his hospitality; he did so, and the savage swallowed all that was thrown to him, with so improving a voracity as if his appetite was but just returning to him. The whole stock of provision was, of course, soon spent, and now his only recourse was to the virtues of his bagpipe; which the monster no sooner heard, than he took to the mountains with the same precipitation he had left them. The poor piper could not so perfectly enjoy his deliverance, but that, with an angry look, at parting, he shook his head, saying, "Ay, are these your tricks? Had I known your humour, you should have had your music before supper."—Bowyer's Anecdotes.

Epitaph on Mr. Nightingale, Architect.

As the birds were the first of the architect kind,And are still better builders than men,What wonders may spring from a Nightingale's mind,When St. Paul's was produced by a Wren.Poets.

The Pyramids.—The Egyptians, according to Herodotus, hated the memory of the kings who built the pyramids. The great pyramid occupied a hundred thousand men for twenty years in its erection, without counting the workmen who were employed in hewing the stones and conveying them to the spot where the pyramid was built. Herodotus speaks of this work as a torment to the people, and doubtless, the labour engaged in raising huge masses of stone, that was extensive enough to employ a hundred thousand men for twenty years, equal to two millions of men for one year, must have been fearfully tormenting. It has been calculated that the steam engines of England worked by thirty-six thousand men, would raise the same quantity of stones from the quarry, and elevate them to the same height as the great pyramid, in the short space of eighteen hours. It was recorded on the pyramid, that the onions, radishes, and garlic, which the labourers consumed, cost sixteen hundred talents of silver, which is equivalent to several million pounds.

SWAINE.

The generality of mankind will not bear to be viewed too closely, or too often: they lose their value on a nearer approach; which made the honest countrymen say to his friend, who was boasting of a legacy bestowed upon him by a person, into whose company he had accidentally fallen only once in his life, "Ah, Jonathan, if he had seen thee twice, he would not have left thee a farthing."

Friendship.—Friendship is of so delicate and so nice a texture, so defenceless against evil impressions, and so apt to wither at the least blast of jealousy, that we may say with Horace,

Felices ter et amplius,Quos irrupta tenet copula; nec malisDivulsus querimoniis,Suprema citius solvet amor die. Ode 13, lib. i."Happy, thrice happy they, whose friendships proveOne constant scene of unmolested love,Whose hearts right temper'd feel no various turns,No coolness chills them, and no madness burns.But free from anger, doubts, and jealous fear,Die as they liv'd, united and sincere."The love between friends is certainly most harmonious when wound up to the highest pitch; but at that very time, is in greatest danger of breaking: and upon the whole, the strongest friendships may be compared to the strongest towns, which are too well fortified to be taken by open attacks; but are always liable to be undermined by treachery or surprise.

A.J.

In the ancient German empire, such persons as endeavoured to sow sedition, and disturb the public tranquillity, were condemned to become objects of public notoriety and derision, by carrying a dog upon their shoulders, from one great town to another. The Emperors, Otho I. and Frederick Barbarossa, inflicted this punishment on noblemen of the highest rank.

1

Recently formed.

2

Quoted in Cunningham's Life of Harlow.

3

A celebrated Hungarian, named Cosmös de Körös, has lately discovered in a Thibetian monastery, where he has been engaged translating an Encyclopaedia, that lithography and movable wooden types were known to the Chinese many centuries ago.

4

A Chinese who leaves his country is considered as a traitor, and is punished with death if he ever return to it.

5

The grand maxim of Confucius is, "to despise foreign commodities."

6

The Chinese use this stimulant as we do wine and spirits, and with perhaps, less deleterious consequences to their health, and less evil results to their morals.

7

About 7,000,000 of which, or bars or moulds of silver to that amount, are sent to India, the Chinese being unable to make sufficient return in merchandise. This remittance is of material assistance in helping to provide funds on the spot for the purchase of tea.

8

A late No. of the Canton Register, mentions a fact, which is one instance out of many, of the desire to be independent of foreigners; it is as follows:—"Prussian blue, an article which was formerly brought in considerable quantities from England, is now totally shut out from the list of imports, in consequence of its mode of manufacture being acquired by a Chinaman in London; and from timely improvement it has been brought to that perfection which renders the consumers independent of foreign supply!"

9

The port dues on a vessel of 1,000 or of 100 tons are alike!

10

The Chinese will not admit a foreign nation to trade at two places; for instance, the Russians are excluded from Canton because they enjoy an overland trade at Kiachia, which is 4,311 miles from St. Petersburgh, and 1,014 miles distant from Pekin.