полная версия

полная версияBehind the Line: A Story of College Life and Football

The problem of finding a man for the position of left half in place of Neil had finally been solved by moving Paul over there from the other side and giving his place to Gillam, a last year substitute. Paul's style of play was very similar to Neil's. He was sure on his feet, a hard, fast runner, and his line-plunging was often brilliant and effective. The chief fault with him was that he was erratic. One day he played finely, the next so listlessly as to cause the coaches to shake their heads. His goal-kicking left something to be desired, but as yet he was as good in that line as any save Neil. Gillam, although light, was a hard line-bucker and a hurdler that was afraid of nothing. In fact he gave every indication of excelling Paul by the time the Robinson game arrived.

One cause of Paul's uneven playing was the fact that he was worried about his studies. He was taking only the required courses, seven in all, making necessary an attendance of sixteen hours each week; but Greek and mathematics were stumbling-blocks, and he was in daily fear lest he find himself forbidden to play football. He knew well enough where the trouble lay; he simply didn't give enough time to study. But, somehow, what with the all-absorbing subject of making the varsity and the hundred and one things that took up his time, the hours remaining for "grinding" were all too few. He wondered how Neil, who seemed quite as busy as himself, managed to give so much time to books.

In one of his weekly evening talks to the football men Mills had strongly counseled attention to study. There was no excuse, he had asserted, for any of the candidates shirking lessons.

"On the contrary, the fact that you are in training, that you are living with proper regard for sleep, good food, fresh air, and plenty of hard physical work, should and does make you able to study better. In my experience, I am glad to say, I have known not one football captain who did not stand among the first few in his class; and that same experience has proved to me that, almost without exception, students who go in for athletics are the best scholars. Healthful exercise and sensible living go hand in hand with scholarly attainment. I don't mean to say that every successful student has been an athlete, but I do say that almost every athlete has been a successful student. And now that we understand each other in this matter, none of you need feel any surprise if, should you get into difficulties with the faculty over your studies, I refuse, as I shall, to intercede in your behalf. I want men to deal with who are honest, hard-working athletes, and honest, hard-working students. My own experience and that of other coachers with whom I have talked, proves that the brilliant football player or crew man who sacrifices class standing for his athletic work may do for a while, but in the end is a losing investment."

And on top of that warning Paul had received one afternoon a printed postal card, filled in here and there with the pen, which was as follows:

"Erskine College, November 4, 1901.

"Mr. Paul Gale.

"Dear Sir: You are requested to call on the Dean, Tuesday, November 5th, during the regular office hours.

"Yours respectfully,

"Ephraim Levett, Dean."

Paul obeyed the mandate with sinking heart. When he left the office it was with a sensation of intense relief and with a resolve to apply himself so well to his studies as to keep himself and the Dean thereafter on the merest bowing acquaintance. And he was, thus far, living up to his resolution; but as less than a week had gone by, perhaps his self-gratulation was a trifle early. It may be that Cowan also was forced to confer with the Dean at about that time, for he too showed an unusual application to text-books, and as a result he and Paul saw each other less frequently.

On November 6th, one week after Neil's accident and just two weeks prior to the Robinson game, Erskine played Arrowden, and defeated her 11-0. Neil, however, did not witness that contest, for, at the invitation of and in company with Devoe, he journeyed to Collegetown and watched Robinson play Artmouth. Devoe had rather a bad knee, and was nursing it against the game with Yale at New Haven the following Saturday. Two of the coaches were also of the party, and all were eager to get an inkling of the plays that Robinson was going to spring on Erskine. But Robinson was reticent. Perhaps her coaches discovered the presence of the Erskine emissaries. However that may have been, her team used ordinary formations instead of tackle-back, and displayed none of the tricks which rumor credited her with having up her sleeve. But the Erskine party saw enough, nevertheless, to persuade them one and all that the Purple need only expect defeat, unless some way of breaking up the tackle-back play was speedily discovered. Robinson's line was heavy, and composed almost altogether of last year material. Artmouth found it well-nigh impregnable, and Artmouth's backs were reckoned good men.

"If we had three more men in our line as heavy and steady as Browning, Cowan, and Carey," said Devoe, "we might hope to get our backs through; but, as it is, they'll get the jump on us, I fear, and tear up our offense before it gets agoing."

"The only course," answered one of the coaches, "is to get to work and put starch into the line as well as we can, and to perfect the backs at kicking and running. Luckily that close-formation has the merit of concealing the point of attack until it's under way, and it's just possible that we'll manage to fool them."

And so Jones and Mills went to work with renewed vigor the next day. But the second team, playing tackle-back after the style of Robinson's warriors, was too much for any defense that the varsity could put up, and got its distance time after time. The coaches evolved and tried several plays designed to stop it, but none proved really successful.

Neil returned to practise that afternoon, his right shoulder protected by a wonderful leather contrivance which was the cause of much good-natured fun. He didn't get near the line-up, however, but was allowed to take part in signal practise, and was then set to kicking goals from placement. If the reader will button his right arm inside his coat and try to kick a ball with accuracy he will gain some slight idea of the difficulty which embarrassed Neil. When work was over he felt as though he had been trying, he declared, to kick left-handed. But he met with enough success to demonstrate that, given opportunity for practise, one may eventually learn to kick goals minus anything except feet.

That happened to be one of Paul's "off days," and the way he played exasperated the coaches and alarmed him. He could not hide from himself the evident fact that Gillam was outplaying him five days a week. With the return of Neil, Paul expected to be ousted from the position of left half, and the question that worried him was whether he would in turn displace Gillam or be sent back to the second eleven. He was safe, however, for several days more, for Simson still laughed at Neil's demand to be put into the line-up, and he was determined that before the Yale game he would prove himself superior to Gillam.

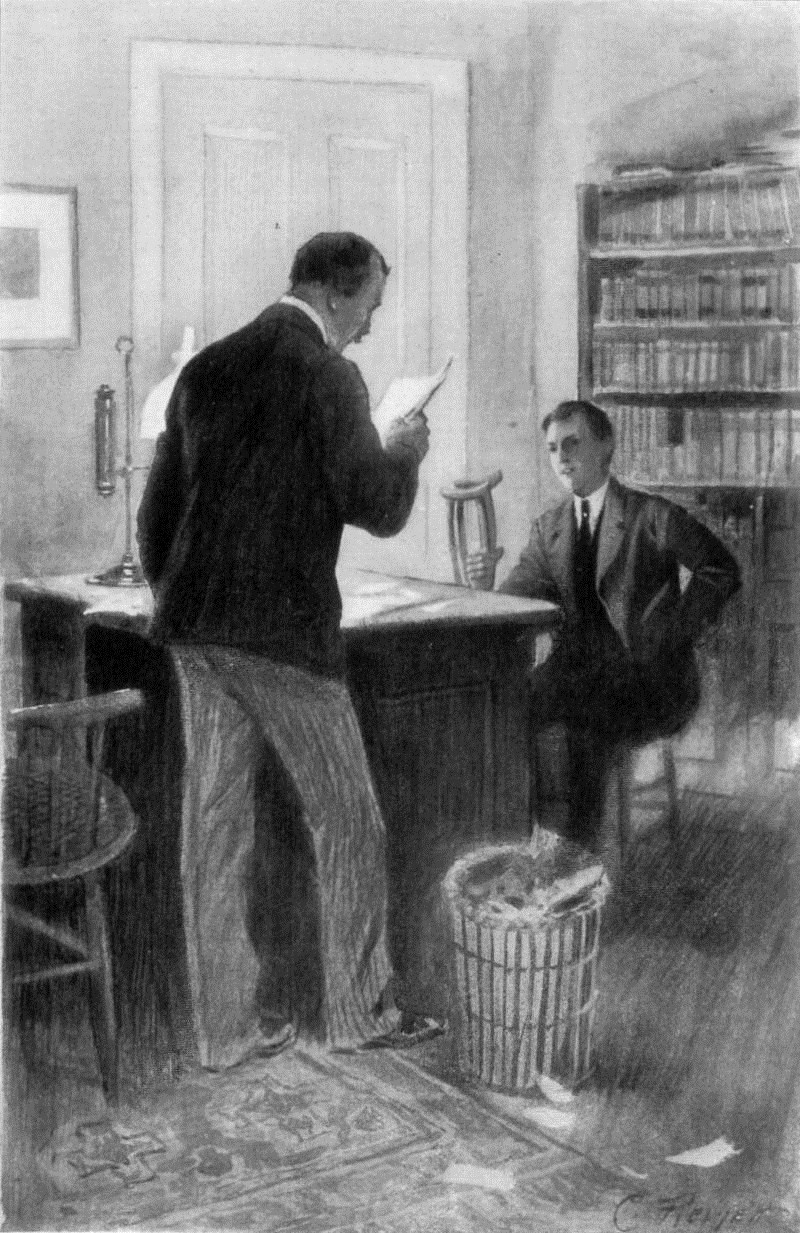

The following morning, Friday, Mills was seated at the desk in his room making out a list of players who were to participate in the Robinson game. According to the agreement between the rival colleges such lists were required to be exchanged not later than two weeks prior to the contest. The players had been decided upon the evening before by all the coaches in assembly, and his task this morning was merely to recopy the list before him. He had almost completed the work when he heard strange sounds outside his door. Then followed a knock, and, in obedience to his request, Sydney Burr pushed open the door and swung himself in on his crutches.

The boy's face was alight with eagerness, and his eyes sparkled with excitement; there was even a dash of color in his usually pale cheeks. Mills jumped up and wheeled forward an easy-chair. But Sydney paid no heed to it.

"Mr. Mills," he cried exultantly, "I think I've got it!"

"Got what?" asked the coach.

"The play we want," answered Sydney, "the play that'll stop Robinson!"

CHAPTER XV

AND TELLS OF A DREAM

Mills's face lighted up, and he stretched forth an eager hand.

"Good for you, Burr! Let's see it. Hold on, though; sit down here first and give me those sticks. There we are. Now fire ahead."

"If you don't mind, I'd like to tell you all about it first, before I show you the diagram," said Sydney, his eyes dancing.

"All right; let's hear it," replied the head coach smiling.

"Well," began Sydney, "it's been a puzzler. After I'd seen the second playing tackle-back I about gave up hopes of ever finding a–an antidote."

"'Antidote's' good," commented Mills laughingly.

"I tried all sorts of notions," continued Sydney, "and spoiled whole reams of paper drawing diagrams. But it was all nonsense. I had the right idea, though, all the time; I realized that if that tandem was going to be stopped it would have to be stopped before it hit our line."

Mills nodded.

"I had the idea, as I say, but I couldn't apply it. And that's the way things stood last night when I went to bed. I had sat up until after eleven and had used up all the paper I had, and so when I got into bed I saw diagrams all over the place and had an awful time to get to sleep. But at last I did. And then I dreamed.

"And in the dream I was playing football. That's the first time I ever played it, and I guess it'll be the last. I was all done up in sweaters and things until I couldn't do much more than move my arms and head. It seemed that we were in 9 Grace Hall, only there was grass instead of floor, and it was all marked out like a gridiron. And everybody was there, I guess; the President and the Dean, and you and Mr. Jones, and Mr. Preston and–and my mother. It was awfully funny about my mother. She kept sewing more sweaters on to me all the time, because, as she said, the more I had on the less likely I was to get hurt. And Devoe was there, and he was saying that it wasn't fair; that the football rules distinctly said that players should wear only one sweater. But nobody paid any attention to him. And after a bit, when I was so covered with sweaters that I was round, like a big ball, the Dean whistled and we got into line–that is," said Sydney doubtfully, "it was sort of like a line. There was the President and Neil Fletcher and I on one side, and all the others, at least thirty of them, on the other. It didn't seem quite fair, but I didn't like to object for fear they'd say I was afraid."

"Well, you did have the nightmare," said Mills. "Then what?"

"The other side got into a bunch, and I knew they were playing tackle-back, although of course they weren't really; they just all stood together. And I didn't see any ball, either. Then some one yelled 'Smash 'em up!' and they started for us. At that Neil–at least I think it was Neil–and Prexy–I mean the President–took hold of me, lifted me up like a bag of potatoes, and hurled me right at the other crowd. I went flying through the air, turning round and round and round, till I thought I'd never stop. Then there was an awful bump, I yelled 'Down!' at the top of my lungs–and woke up. I was on the floor."

Mills laughed, and Sydney took breath.

"At first I didn't know what had happened. Then I remembered the dream, and all on a sudden, like a flash of lightning, it occurred to me that that was the way to stop tackle-back!"

"That? What?" asked Mills, looking puzzled.

"Why, the bag of potatoes act," laughed Sydney. "I jumped up, lighted the gas, got pencil and paper and went back to bed and worked it out. And here it is."

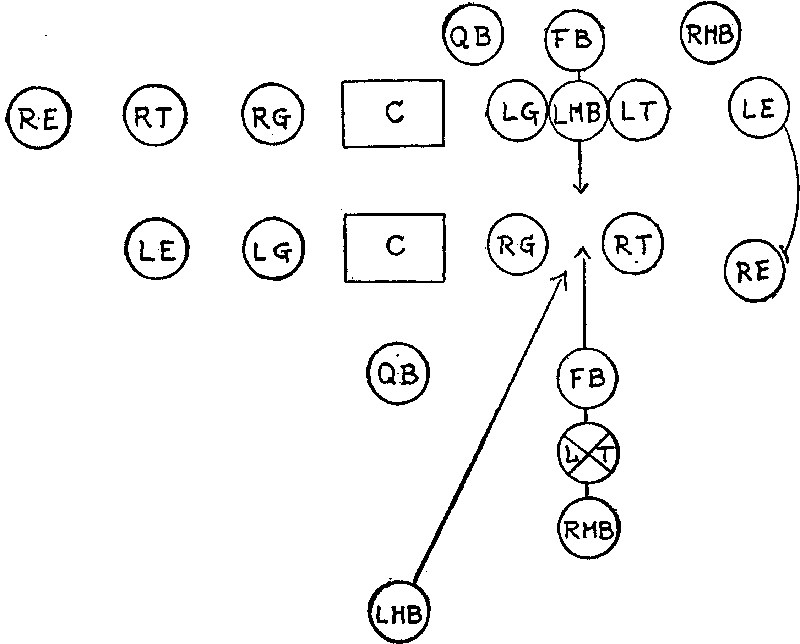

He drew a carefully folded slip of paper from his pocket and handed it across to Mills. The diagram, just as the head coach received it, is reproduced here.

Mills studied it for a minute in silence; once he grunted; once he looked wonderingly up at Sydney. In the end he laid it beside him on the desk.

"I think you've got it, Burr," he said quietly, "I think you've got it, my boy. If this works out the way it should, your nightmare will be the luckiest thing that's happened at Erskine for several years. Draw your chair up here–I beg your pardon; I forgot. I'll do the moving myself." He placed his own chair beside Sydney's and handed the diagram to him. "Now just go over this, will you; tell me just what your idea is."

Mills studied the diagram in silence.

Sydney, still excited over the night's happenings, drew a ready pencil from his pocket, and began rather breathlessly:

"I've placed the Robinson players in the positions that our second team occupies for the tackle-tandem. Full-back, left tackle, and right half, one behind the other, back of their guard-tackle hole. Now, as the ball goes into play their tandem starts. Quarter passes the ball to tackle, or maybe right half, and they plunge through our line. That's what they would do if we couldn't stop them, isn't it?"

"They would, indeed," answered Mills grimly. "About ten yards through our line!"

"Well, now we place our left half in our line between our guard and tackle, and put our full-back behind him, making a tandem of our own. Quarter stands almost back of guard, and the other half over here. When the ball is put in play our tandem starts at a jump and hits the opposing tandem just at the moment their quarter passes the ball to their runner. In other words, we get through on to them before they can get under way. Our quarter and right half follow up, and, unless I'm away off on my calculations, that tackle-tandem is going to stop on its own side of the line."

Sydney paused and awaited Mills's opinion. The latter was silent a moment. Then–

"Of course," he said, "you've thought of what's going to happen to that left half?"

"Yes," answered Sydney, "I have. He's going to get most horribly banged up. But he's going to stop the play."

"Yes, I think he is–if he lives," said Mills with a grim smile. "The only objection that occurs to me this moment is this: Have we the right to place any player in a position like this where the punishment is certain to be terrific, if not absolutely dangerous?"

"I've thought of that, too," answered Sydney readily. "And I don't believe we–er–you have."

"Well, then I think our play's dished at the start."

"Why, not a bit, sir. Call the players up, explain the thing to them, and tell them you want a man for that position."

"Ah, ask for volunteers, eh?"

"Yes, sir. And you'll have just as many, I'll bet, as there are men!"

Mills smiled.

"Well, it's a desperate remedy, but I believe it's the only one, and we'll see what can be done. By the way, I observe that you've taken left half for the victim?"

"Yes, sir; that's Neil Fletcher. He's the fellow for it, I think."

"But I thought he was a friend of yours," laughed Mills.

"So he is; that's why I want him to get it; he won't ask anything better. And he's got the weight and the speed. The fellow that undertakes it has got to be mighty quick, and he's got to have weight and plenty of grit. And that's Neil."

"Yes, I think so too. But I don't want him to get used up and not be able to kick, for we'll need a field-goal before the game is over, if I'm not greatly mistaken. However, we can find a man for that place, I've no doubt. For that matter, we must find two at least, for one will never last the game through."

"I suppose not. I–I wish I had a chance at it," said Sydney longingly.

"I wish you had," said Mills. "I think you'd stand all the punishment Robinson would give you. But don't feel badly that you can't play; as long as you can teach the rest of us the game you've got honor enough."

Sydney flushed with pleasure, and Mills took up the diagram again.

"Guard and tackle will have their work cut out for them," he said. "And I'm not sure that left end can't be brought into it, too. There's one good feature about Robinson's formation, and that is we can imagine where it's coming as long as it's a tandem. If we stop them they'll have to try the ends, and I don't think they'll make much there. Well, we'll give this a try to-morrow, and see how it works. By the way, Burr," he went on, "you can get about pretty well on your crutches, can't you?"

"Yes," Sydney answered.

"Good. Then what's to prevent you from coming out to the field in the afternoons and giving us a hand with this? Do you think you could afford the time?"

Sydney's eyes dropped; he didn't want Mills to see how near the tears were to his eyes.

"I can afford the time all right," he answered in a voice that, despite his efforts, was not quite steady, "if you really think I can be of any use."

Perhaps Mills guessed the other's pleasure, for he smiled gently as he answered:

"I don't think; I'm certain. You know this play better than I do; it's yours; you know how you want it to go. You come out and look after the play; we'll attend to the players. And then, if we find a weak place in it, we can all get together and remedy it. But you oughtn't to try and wheel yourself out there and back every day. You tell me what time you can be ready each afternoon and I'll see that there's a buggy waiting for you."

"Oh, no, really!" Sydney protested. "I'd rather not! I can get to the field and back easily, without getting at all tired; in fact, I need the exercise."

"Well, if you're certain of that," answered the coach. "But any time you change your mind, or the weather's bad, let me know. If you can, I'd like you to come around here again this evening. I'll have Devoe and the coaches here, and we'll talk this–this 'antidote' over again. Well, good-by."

Sydney swung himself to the door, followed by Mills, and got into his tricycle.

"About eight this evening, if you can make it, Burr," said Mills. "Good-by." He stood at the door and watched the other as he trundled slowly down the street.

"Poor chap!" he muttered. And then: "Still, I'm not so sure that he's an object of pity. If he hasn't any legs worth mentioning, the Almighty made it up to him by giving him a whole lot of brains. If he can't get about like the rest of us he's a great deal more contented, I believe, and if he can't play football he can show others how to. And," he added, as he returned to his desk, "unless I'm mistaken, he's done it to-day. Now to mail this list and then for the 'antidote'!"

That night in Mills's room the assembled coaches and captain talked over Sydney's play, discussed it from start to finish, objected, explained, argued, tore it to pieces and put it together again, and in the end indorsed it. And Sydney, silent save when called on for an explanation of some feature of his discovery, sat with his crutches beside his chair and listened to many complimentary remarks; and at ten o'clock went back to Walton and bed, only to lie awake until long after the town-clock had struck midnight, excited and happy.

Had you been at Erskine at any time during the following two weeks and had managed to get behind the fence, you would have witnessed a very busy scene. Day after day the varsity and the second fought like the bitterest enemies; day after day the little army of coaches shouted and fumed, pleaded and scolded; and day after day a youth on crutches followed the struggling, panting lines, instructing and criticizing, and happier than he had been at any time in his memory.

For the "antidote," as they had come to call it, had been tried and had vindicated its inventor's faith in it. Every afternoon the second team hammered the varsity line with the tackle-tandem, and almost every time the varsity stopped it and piled it up in confusion. The call for volunteers for the thankless position at the front of the little tandem of two had resulted just as Sydney had predicted. Every candidate for varsity honors had begged for it, and some half dozen or more had been tried. But in the end the choice had narrowed down to Neil, Paul, Gillam, and Mason, and these it was that day after day bore the brunt of the attack, emerging from each pile-up beaten, breathless, scarred, but happy and triumphant. Two weeks is short time in which to teach a new play, but Mills and the others went bravely and confidently to work, and it seemed that success was to justify the attempt; for three days before the Robinson game the varsity had at last attained perfection in the new play, and the coaches dared at last to hope for victory.

But meanwhile other things, pleasant and unpleasant, had happened, and we must return to the day which had witnessed the inception of Sydney Burr's "antidote."

CHAPTER XVI

ROBINSON SENDS A PROTEST

When Sydney left Mills that morning he trundled himself along Elm Street to Neil's lodgings in the hope of finding that youth and telling him of his good fortune. But the windows of the first floor front study were wide open, the curtains were hanging out over the sills, and from within came the sound of the broom and clouds of dust. Sydney turned his tricycle about in disappointment and retraced his path, through Elm Lane, by the court-house with its tall white pillars and green shutters, across Washington Street, the wheels of his vehicle rustling through the drifts of dead leaves that lined the sidewalks, and so back to Walton. He had a recitation at half-past ten, but there was still twenty minutes of leisure according to the dingy-faced clock on the tower of College Hall. So he left the tricycle by the steps, and putting his crutches under his arms, swung himself into the building and down the corridor to his study. The door was ajar and he thrust it open with his foot.

"Please be careful of the paint," expostulated a voice, and Sydney paused in surprise.

"Well," he said; "I've just been over to your room looking for you."

"Have you? Sorry I wasn't–Say, Syd, listen to this." Neil dragged a pillow into a more comfortable place and sat up. He had been stretched at full length on the big window-seat. "Here it is in a nutshell," he continued, waving the paper he was reading.

"'First a signal, then a thud, And your face is in the mud. Some one jumps upon your back, And your ribs begin to crack. Hear a whistle. "Down!" That's all. 'Tis the way to play football.'""Pretty good, eh? Hello, what's up? Your face looks as bright as though you'd polished it. How dare you allow your countenance to express joy when in another quarter of an hour I shall be struggling over my head in the history of Rome during the second Punic War? But there, go ahead; unbosom yourself. I can see you're bubbling over with delightful news. Have they decided to abolish the Latin language? Or has the faculty been kidnaped? Have they changed their minds and decided to take me with 'em to New Haven to-morrow? Come, little Bright Eyes, out with it!"

Sydney told his good news, not without numerous eager interruptions from Neil, and when he had ended the latter executed what he called a "Punic war-dance." It was rather a striking performance, quite stately and impressive, for when one's left shoulder is made immovable by much bandaging it is difficult, as Neil breathlessly explained, to display abandon--the latter spoken through the nose to give it the correct French pronunciation.

"And, if you're not good to me," laughed Sydney, "I'll get back at you in practise. And I'm to be treated with respect, also, Neil; in fact, I believe you had better remove your cap when you see me."

"All right, old man; cap–sweater–anything! You shall be treated with the utmost deference. But seriously, Syd, I'm awfully glad. Glad all around; glad you've made a hit with the play, and glad you've found something to beat Robinson with. Now tell me again about it; where do I come in on it?"

And so Sydney drew a chair up to the table and drew more diagrams of the new play, and Neil looked on with great interest until the bell struck the half-hour, and they hurried away to recitations.

The next day the varsity and substitutes went to New Haven. Neil wasn't taken along, and so when the result of the game reached the college–Yale 40, Erskine 0–he was enabled to tell Sydney that it was insanity for Mills and Devoe to expect to do anything without his (Neil's) services.