полная версия

полная версияBehind the Line: A Story of College Life and Football

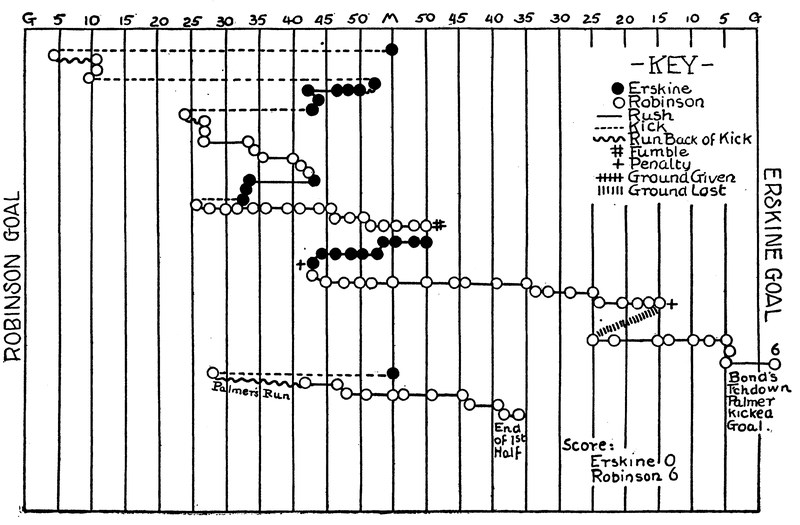

Robinson now had the ball near her thirty-five yards and returned to the tackle-tandem. In two plays she gained two yards, the result of faster playing. Then another try outside of right tackle brought her five yards. Tackle-tandem again, one yard; again, two yards; a try outside of tackle, one yard; Erskine's ball on Robinson's forty-three yards. The pigskin went to Gillam, who got safely away outside Robinson's right end and reeled off ten yards before he was caught. Again he was given the ball for a plunge through right tackle and barely gained a yard. Mason found another yard between left-guard and tackle and Foster kicked. It was poorly done, and the leather went into touch at the twenty-five yards, and once more Robinson set her feet toward the Erskine goal.

So far the playing had all been done in her territory and her coaches were looking anxious. Erskine's defense was totally unlooked for, both as regarded style and effectiveness, and the problem that confronted them was serious. Their team had been perfected in the tackle-tandem play to the neglecting of almost all else. Their backs were heavy and consequently slow when compared with their opponents. To be sure, thus far runs outside of tackle and end had been successful, but the coaches well knew that as soon as Erskine found that such plays were to be expected she would promptly spoil them. Kicking was not a strong point with Robinson this year; at that game her enemy could undoubtedly beat her. Therefore, if the tackle-back play didn't work what was to be done? There was only one answer: Make it! There was no time or opportunity now to teach new tricks; Robinson must stand or fall by tackle-tandem. And while the coaches were arriving at this conclusion, White, their captain and quarter-back, had already reached it.

He placed the head of the tandem nearer the line, put the tackle at the head of it, and hammered away again. Mills, seeing the move, silently applauded. It was the one way to strengthen the tandem play, for by starting nearer the line the tandem could possibly reach it before the charging opponents got into the play. Momentum was sacrificed and an instant of time gained, and, as it proved, that instant of time meant a difference of fully a yard on each play. Had the two Erskine warriors whose duty it was to hurl themselves against the tandem been of heavier weight it is doubtful if the change made would have greatly benefited their opponents; but, as it was, the two forces met about on Robinson's line, and after the first recoil the Brown was able to gain, sometimes a bare eighteen inches, sometimes a yard, once or twice three or four.

And now Robinson took up her march steadily toward the Purple's goal. The backs plowed through for short distances; Gillam and Paul bore the brunt of the terrific assaults heroically; the Erskine line fell back foot by foot, yard by yard; and presently Robinson crossed the fifty-five-yard line and emerged into Erskine territory. Here there was a momentary pause in her conquering invasion. A fumble by the full-back allowed Devoe to get through and fall on the ball.

Erskine now knifed the Brown's line here and there and shot Gillam and Paul through for short gains and made her distance. Then, with the pigskin back in Robinson territory, Erskine was caught holding and Robinson once more took up her advance. Carey at right tackle weakened and the Brown piled her backs through him. On Erskine's thirty-two yards he gave place to Jewell and the tandem moved its attack to the other side of the line. Paul and Gillam, both pretty well punished, still held out stubbornly. Yard by yard the remaining distance was covered. On her fifteen yards, almost under the shadow of her goal-posts, Erskine was given ten yards for off-side play, and the waning hopes of the breathless watchers on the north stand revived.

But from the twenty-five-yard line the steady rushes went on again, back over the lost ground, and soon, with the half almost gone, Robinson placed the ball on Erskine's five yards. Twice the tandem was met desperately and hurled back, but on the third down, with her whole back-field behind the ball, Robinson literally mowed her way through, sweeping Paul and Mason, and Gillam and Foster before her, and threw Bond over between the posts with the ball close snuggled beneath him.

The south stand leaped to its feet, blue flags and streamers fluttered and waved, and cheers for Robinson rent the air until long after the Brown's left half had kicked a goal. Then the two teams faced each other again and the Robinson left end got the kick-off and ran it back fifteen yards. Again the battering of the tackle-tandem began, and Paul and Gillam, nearly spent, were unable to withstand it after the first half dozen plays. Mason went into the van of the defense in place of Gillam, but the Brown's advance continued; one yard, two yards, three yards were left behind.

Mills, watching, glanced almost impatiently at the timekeeper, who, with his watch in hand, followed the battle along the side-line. The time was almost up, but Robinson was back on Erskine's thirty-five yards. But now the timekeeper walked on to the gridiron, his eyes fixed intently on the dial, and ere the ball went again into play he had called time. The lines broke up and the two teams trotted away.

The score-board proclaimed:

Erskine 0, Opponents 6.

CHAPTER XXII

BETWEEN THE HALVES

Neil trotted along at the tail-end of the procession of substitutes, so deep in thought that he passed through the gate without knowing it, and only came to himself when he stumbled up the locker-house steps. He barked his shins and reached a conclusion at the same instant.

At the door of the dressing-room a strong odor of witch-hazel and liniment met him. He squeezed his way past a group of coaches and looked about him. Confusion reigned supreme. Rubbers and trainer were hard at work. Simson's voice, commanding, threatening, was raised above all others, a shrill, imperious note in a rising and falling babel of sound. Veterans of the first half and substitutes chaffed each other mercilessly. Browning, with an upper lip for all the world like a piece of raw beef, mumbled good-natured retorts to the charges brought against him by Reardon, the substitute quarter-back.

Erskine vs. Robinson–The First Half.

"Yes, you really ought to be careful," the latter was saying with apparent concern. "If you let those chaps throw you around like that you may get bruised or broken. I'll speak to Price and ask him to be more easy with you."

"Mmbuble blubble mummum," observed Browning.

"Oh, don't say that," Reardon entreated.

Neil was looking for Paul, and presently he discovered him. He was lying on his back while a rubber was pommeling his neck and shoulders violently and apparently trying to drown him in witch-hazel. He caught sight of Neil and winked one highly discolored eye. Neil examined him gravely; Paul grinned.

"There's a square inch just under your left ear, Paul, that doesn't appear to have been hit. How does that happen?"

Paul grinned more generously, although the effort evidently pained him.

"It's very careless of them, I must say," Neil went on sternly. "See that it is attended to in the next half."

"Don't worry," answered Paul, "it will be." Neil smiled.

"How are you feeling?" he asked.

"Fine," Paul replied. "I'm just getting limbered up."

"You look it," said Neil dryly. "I suppose by the time your silly neck is broken you'll be in pretty good shape to play ball, eh?" Simson hurried up, closely followed by Mills.

"How's the neck?" he asked.

"It's all right now," answered Paul. "It felt as though it had been driven into my body for about a yard."

"Do you think you can start the next half?" asked Mills anxiously.

"Sure; I can play it through; I'm all right now," replied Paul gaily. Mills's face cleared.

"Good boy!" he muttered, and turned away. Neil sped after him.

"Mr. Mills," he called. The head coach turned, annoyed by the interruption.

"Well, Fletcher; what is it?"

"Can't I get in for a while, sir?" asked Neil earnestly. "I'm feeling fine. Gillam can't last the game, nor Paul. I wish you'd let–"

"See Devoe about it," answered Mills shortly. He hurried away, leaving Neil with open mouth and reddening cheeks.

"Well, that's what I get for disappointing folks," he told himself. "Only he needn't have been quite so short. What's the good of asking Devoe? He won't let me on. And–but I'll try, just the same. Paul's had his chance and there's no harm now in looking after Neil Fletcher."

He found Devoe with Foster and one of the coaches. The latter was lecturing them forcibly in lowered tones, and Neil hesitated to interrupt; but while he stood by undecided Devoe glanced up, his face a pucker of anxiety. Neil strode forward.

"Say, Bob, get me on this half, can't you? Mills told me to see you," he begged. "Give me a chance, Bob!"

Devoe frowned impatiently and shook his head.

"Can't be done, Neil. Mills has no business sending you to me. He's looking after the fellows himself. I've got troubles enough of my own."

"But if I tell him you're willing?" asked Neil eagerly.

"I'm not willing," said Devoe. "If he wants you he'll put you on. Don't bother me, Neil, for heaven's sake. Talk to Mills."

Neil turned away in disappointment. It was no use. He knew he could play the game of his life if only they'd take him on. But they didn't know; they only knew that he had been tried and found wanting. There was no time now to test doubtful men. Mills and Devoe and Simson were not to be blamed; Neil recognized that fact, but it didn't make him happy. He found a seat on a bench near the door and dismally looked on. Suddenly a conversation near at hand engaged his attention.

Mills, Jones, Sydney Burr, and two other assistant coaches were gathered together, and Mills was talking.

"The 'antidote's' all right," he was saying decidedly. "If we had a team that equaled theirs in weight we could stop them short; but they're ten pounds heavier in the line and seven pounds heavier behind it. What can you expect? Without the 'antidote' they'd have had us snowed under now; they'd have scored five or six times on us."

"Easy," said Jones. "The 'antidote's' all right, Burr. What we need are men to make it go. That's why I say take Gillam out. He's played a star game, but he's done up now. Let Pearse take his place, play Gale as long as he'll last, and then put in Smith. How about Fletcher?"

"No good," answered Mills. "At least–" He stopped and narrowed his eyes, as was his way when thinking hard.

"I think he'd be all right, Mr. Mills," said Sydney. "I–I know him pretty well, and I know he's the sort of fellow that will fight hardest when the game's going wrong."

"I thought so, too," answered Mills; "but–well, we'll see. Maybe we'll give him a try. Time's up now.–O Devoe!"

"Yes, coming!"

"Here's your list. Better get your men out."

There was a hurried donning of clothing, a renewed uproar.

"All ready, fellows," shouted the captain. "Answer to your names: Kendall, Tucker, Browning, Stowell, Witter, Jewell, Devoe, Gale, Pearse, Mason, Foster."

"There's not much use in talk," said Mills, as the babel partly died away. "I've got no fault to find with the work of any of you in the last half; but we've got to do better in this half; you can see that for yourselves. You were a little bit weak on team-play; see if you can't get together. We're going to tie the score; maybe we're going to beat. Anyhow, let's work like thunder, fellows, and, if we can't do any more, tear that confounded tackle-tandem up and send it home in pieces. We've got thirty-five minutes left in which to show that we're as good if not better than Robinson. Any fellow that thinks he's not as good as the man he's going to line up against had better stay out. I know that every one of you is willing, but some of you appeared in the last half to be laboring under the impression that you were up against better men. Get rid of that idea. Those Robinson fellows are just the same as you–two legs, two arms, two eyes, a nose, and a mouth. Go at it right and you can put them out of the play. Remember before you give up that the other man's just as tuckered as you are, maybe more so. Your captain says we can win out. I think he knows more about it than we fellows on the side-line do. Now go ahead, get together, put all you've got into it, and see whether your captain knows what he's talking about. Let's have a cheer for Erskine!"

Neil stood up on the bench and got into that cheer in great shape. He was feeling better. Mills had half promised to put him in, and while that might mean much or nothing it was ground for hope. He trotted on to the field and over to the benches almost happily.

The spectators were settling back in their seats, and the cheering had begun once more. The north stand had regained its spirit. After all, the game wasn't lost until the last whistle blew, and there was no telling what might happen before that. So the student section cheered and sang, the band heroically strove to make itself heard, and the purple flags tossed and fluttered. The sun was almost behind the west corner of the stand, and overcoat collars and fur neck-pieces were being snuggled into place. From the west tiers of seats came the steady tramp-tramp of chilled feet, hinting their owners' impatience.

The players took their places, silence fell, and the referee's whistle blew. Robinson kicked off, and the last half of the battle began.

CHAPTER XXIII

NEIL GOES IN

But what a dismal beginning it was!

Pearse, who had taken Gillam's place at right half-back, misjudged the long, low kick, just managed to tip the ball with one outstretched hand as it went over his head, and so had to turn and chase it back to the goal-line. But Mason had seen the danger and was before him. Seizing the bouncing pigskin, he was able to reach the ten-yard line ere the Robinson right end bore him to earth. A moment later the ball went to the other side as a penalty for holding, and it was Robinson's first down on Erskine's twelve yards. Neil, watching intently from the bench, groaned loudly. Stone, beside him, kicked angrily into the turf.

"That settles it," he muttered glumly. "Idiots!"

Pearse it was who met that first fierce onslaught of the Brown's tandem, and he was new to the play; but Mason was behind him, and he was sent crashing into the leader like a ball from the mouth of a cannon. The tandem stopped; a sudden bedlam of voices from the stands broke forth; there were cries of "Ball! Ball!" and Witter flung himself through, rolled over a few times, and on the twenty-yard line, with half the Erskine team striving to pull him on and all the Robinson team trying to pull him back, groaned a faint "Down!" Robinson's tackle had fumbled the pass, and for the moment Erskine's goal was out of danger.

"Line up!" shouted Ted Foster. "Signal!"

The men scurried to their places.

"49–35–23!"

Back went the ball and Pearse was circling out toward his own left end, Paul interfering. The north stand leaped to its feet, for it looked for a moment as though the runner was safely away. But Seider, the Brown's right half, got him about the knees, and though Pearse struggled and was dragged fully five yards farther, finally brought him down. Fifteen yards was netted, and the Erskine supporters found cause for loud acclaim.

"Bully tackle, that," said Neil. Stone nodded.

"Seems to me we can get around those ends," he muttered; "especially the left. I don't think Bloch is much of a wonder. There goes Pearse."

The ends were again worked by the two half-backs and the distance thrice won. The purple banners waved ecstatically and the cheers for Erskine thundered out. Neil was slapping Stone wildly on the knee.

"Hold on," protested the left end, "try the other. That one's a bit lame."

"Isn't Pearse a peach?" said Neil. "Oh, but I wish I was out there!"

"You may get a whack at it yet," answered Stone. "There goes a jab at the line."

"I may," sighed Neil. He paused and watched Mason get a yard through the Brown's left tackle. "Only, if I don't, I suppose I won't get my E."

"Oh, yes, you will. The Artmouth game counts, you know."

"I wasn't in it."

"That's so, you weren't; I'd forgotten. But I think you'll get it, just the–Good work, Gale!" Paul had made four yards outside of tackle, and it was again Erskine's first down on the fifty-five-yard line. The cheers from the north stand were continuous; Neil and Stone were obliged to put their heads together to hear what each other said.

For five minutes longer Erskine's wonderful good fortune continued, and the ball was at length on Robinson's twenty-eight yards near the north side-line. Foster was waving his hand entreatingly toward the seats, begging for a chance to make his signals heard. From across the field, in the sudden comparative stillness of the north stand, thundered the confident slogan of Robinson. The brown-stockinged captain and quarter-back was shouting incessantly:

"Steady now, fellows! Break through! Break through! Smash 'em up!" He ran from one end to the other, thumping each encouragingly on the back, whispering threats and entreaties into their ears. "Now, then, Robinson, let's stop 'em right here!"

Foster, red-faced and hoarse, leaned forward, patted Stowell on the thigh, caught the ball, passed it quickly to Mason as that youth plunged for the line, and then threw himself into the breach, pushing, heaving, fighting for every inch that gave under his torn and scuffled shoes.

"Second down; four to gain!"

Robinson was awake now to her danger. Foster saw the futility of further attempts at the line for the present and called for a run around left end. The ball went to Pearse, but Bloch for once was ready for him, and, getting by Kendall, nailed the runner prettily four yards back of the line to the triumphant pæans of the south stand.

When the teams had again lined up Foster dropped back as though to try a kick for goal, a somewhat difficult feat considering the angle. The Robinson captain was alarmed; he was ready to believe that a team who had already sprung one surprise on him was capable of securing goals from any angle whatever; his voice arose in hoarse entreaty:

"Get through and block this kick, fellows! Get through! Get through!"

"Signal!" cried Foster. "44–18–23!"

The ball flew back from Stowell and Foster caught it breast-high. The Erskine line held for a moment, then the blue-clad warriors came plunging through desperately, and had Foster attempted a kick the ball would never have gone ten feet; but Foster, who knew his limitations in the kicking line as well as any one else, had entertained no such idea. The pigskin, fast clutched to Paul's breast, was already circling the Brown's left end. Devoe had put his opponent out of the play, thereby revenging himself for like treatment in the first half, and Pearse, a veritable whirlwind, had bowled over the Robinson left half. There is, perhaps, no prettier play than a fake kick, when it succeeds, and the friends of Erskine recognized the fact and showed their appreciation in a way that threatened to shake the stand from its foundations.

Paul and Pearse were circling well out in the middle of the field toward the Robinson goal, now some thirty yards distant measured by white lines, but far more than that by the course they were taking. Behind them streamed a handful of desperate runners; before them, rapidly getting between them and the goal, sped White, the Robinson captain and quarter. To the spectators a touch-down looked certain, for it was one man against two; the pursuit was not dangerous. But to Paul it seemed at each plunge a more forlorn attempt. So far he had borne more than his share of the punishment sustained by the tackle-tandem defense; he had worked hard on offense since the present half began, and now, wearied and aching in every bone and muscle, he found himself scarce able to keep pace with his interference.

He would have yielded the ball to Pearse had he been able to tell the other to take it; but his breath was too far gone for speech. So he plunged onward, each step slower than that before, his eyes fixed on the farthest white streak. From three sides of the great field poured forth the resonance of twelve thousand voices, triumphant, despairing, appealing, inciting, the very acme of sound.

Yet Paul vows that he heard nothing save the beat of Pearse's footsteps and the awful pounding of his own heart.

On the fifteen-yard line, just to the left of the goal, the critical moment came. White, with clutching, outstretched hands, strove to evade Pearse's shoulder, and did so. But the effort cost him what he gained, for, dodging Pearse and striving to make a sudden turn toward Paul, his foot slipped and he measured his length on the turf; and ere he had regained his feet the pursuit passed over him. Pearse met the first runner squarely and both went down. At the same instant Paul threw up one hand blindly and fell across the last line.

On the north stand hats and flags sailed through the air. The south stand was silent.

Paul lay unmoving where he had fallen. Simson was at his side in a moment. Neil, his heart thumping with joy, watched anxiously from the bench. Presently the group dissolved and Paul emerged between Simson and Browning, white of face and stumbling weakly on his legs, but grinning like a jovial satyr. Mills turned to the bench and Neil's heart jumped into his throat; but it was Smith and not he who struggled feverishly out of his sweater, donned a head-harness, and sped on to the field. Neil sighed and sank back.

"Next time," said Stone sympathetically. But Neil shook his head.

"I guess there isn't going to be any 'next time,'" he said dolefully. "Time's nearly up."

"Not a bit of it; the last ten minutes is longer than all the rest of the game," answered Stone. "I wonder who'll try the goal."

"We've got to have it," said Neil. "Surely Devoe can kick an easy one like that! Why, it's dead in the center!" Stone shook his head.

"I know, but Bob's got a bad way of getting nervous times like this. He knows that if he misses we've lost the game, unless we can manage to score again, which isn't likely; and it's dollars to doughnuts he doesn't come anywhere near it!"

Paul staggered up to the bench, Simson carefully wrapping a blanket about him, and the fellows made room for him a little way from where Neil sat. He stretched his long legs out gingerly because of the aches, sighed contentedly, and looked about him. His eyes fell on Neil.

"Hello, chum!" he said weakly. "Haven't you gone in yet?"

"Not yet," answered Neil cheerfully. "How are you feeling?"

"Oh, I'm–ouch!–I'm all right; a bit sore here and there."

"Devoe's going to kick," said Stone uneasily.

The ball had been brought out, and now Foster was holding it directly in front of the center of the cross-bar. The south stand was cheering and singing wildly in a desperate attempt to rattle the Erskine captain. The latter looked around once, and the Robinson supporters, taking that as a sign of nervousness, redoubled their noise.

"Muckers!" groaned Neil. Stone grinned.

"Everything goes with them," he said.

The referee's hand went down, Devoe stepped forward, the blue-clad line leaped into the field, and the ball sped upward. As it fell Neil turned to Stone and the two stared at each other in doubt. From both stands arose a confused roar. Then their eyes sought the score-board at the west end of the field and they groaned in unison.

"NO GOAL."

"What beastly luck!" muttered Stone.

Neil was silent. Mills and Jones were standing near by and looking toward the bench and Neil imagined they were discussing him. He watched breathlessly, then his heart gave a suffocating leap and he was racing toward the two coaches.

"Warm up, Fletcher."

That was all, but it was all Neil asked for. In a twinkling he was trotting along the line, stretching his cramped legs and arms. As he passed the bench he tried to look unconcerned, but the row of kindly, grinning faces told him that his delight was common property. Paul silently applauded.