Полная версия

Byzantium: The Enduring Legacy and Hidden Secrets of the Great Empire

Viktor Nikitin

Byzantium: The Enduring Legacy and Hidden Secrets of the Great Empire

For over a thousand years, it was a cultural and strategic bridge between continents, a living continuation of Rome and a shield for Europe.

The Byzantine Empire’s unparalleled longevity, spanning more than a millennium, stands as a testament to its extraordinary ability to endure, adapt, and influence the course of world history. It was neither a mere relic of the ancient Roman world nor a stagnant civilization locked in the past. Instead, Byzantium emerged as a dynamic and resilient political and cultural entity, embodying the complex interplay of continuity and change, synthesis and innovation.

Foundation and Geopolitical Significance

Founded as Constantinople in 330 AD by Emperor Constantine the Great, the city was deliberately positioned on the strategic Bosporus strait, controlling the gateway between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. This choice was not accidental; it reflected a vision to establish a "New Rome" that would command trade routes, secure military advantage, and assert Christian imperial authority. Constantinople’s natural harbor, formidable walls, and access to key resources made it an impregnable fortress city and a vibrant center of commerce and culture.

Byzantium sat astride the boundary between Europe and Asia, functioning as a bridge—not only geographically but also culturally, religiously, and economically. It connected the Latin West with the Greek East, the Christian world with the Muslim caliphates, and the ancient world with the emerging medieval order. Merchants from Venice, Alexandria, Baghdad, and beyond brought goods, ideas, and religions to its bustling markets, turning the city into one of the most cosmopolitan urban centers of its time.

Cultural Synthesis and Intellectual Vitality

The Byzantine Empire was the crucible where Greco-Roman heritage merged with Christian theology and Near Eastern traditions, producing a civilization unique in its depth and complexity. Byzantine education fostered the study of classical texts—philosophy, rhetoric, medicine, and history—while simultaneously promoting Christian learning. This synthesis gave rise to remarkable scholars such as John of Damascus, whose theological works bridged classical philosophy and Christian doctrine.

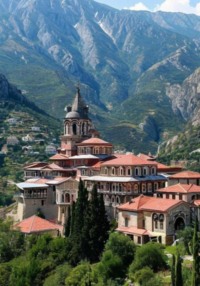

The empire's artistic achievements reflect this cultural amalgamation. The mosaics of Ravenna, the icon paintings of Mount Athos, and the architectural innovations of Hagia Sophia exemplify a spiritual and aesthetic worldview that sought to express divine mystery through grandeur and symbolism. These works inspired both Orthodox Christianity and Western art, leaving a lasting impression on the Christian world.

Legal and Administrative Legacy

One of Byzantium’s most enduring contributions to civilization was its legal codification under Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century. The Corpus Juris Civilis systematically compiled and harmonized centuries of Roman law, ensuring its preservation and transmission to later European legal systems. Its principles underpin modern civil law traditions across much of Europe, influencing concepts of property, contract, and justice.

Administratively, Byzantium’s complex bureaucracy managed an empire that stretched from the Balkans to Egypt and from Anatolia to the Levant. The imperial court in Constantinople was a center of political power and ceremonial grandeur, where the emperor wielded authority not only as a secular ruler but also as a divine representative on earth. This fusion of spiritual and temporal power underpinned Byzantine governance and diplomacy.

Religious Centrality and Spiritual Identity

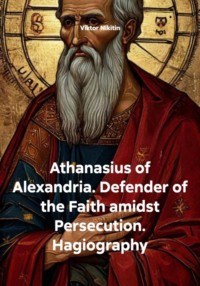

The Byzantine Empire’s identity was inseparable from its role as the defender and promoter of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. The conversion of Emperor Constantine and the subsequent adoption of Christianity as the state religion transformed the empire’s character. The emperor was viewed as the protector of the faith, tasked with preserving doctrinal purity and enforcing religious unity.

This religious mission was embodied in the architecture of Constantinople, especially in the Hagia Sophia, whose soaring dome symbolized the heavens and divine order. Byzantine liturgy, music, and iconography deeply influenced Orthodox spirituality, shaping religious practice for centuries in Eastern Europe and the Near East.

Military and Strategic Prowess

From its inception, Byzantium was a military state, engaged in near-constant conflict to defend its borders against a succession of threats—Goths, Huns, Slavs, Arabs, and Turks. The empire developed sophisticated military institutions, combining standing armies, elite guard units like the Varangians, and an extensive network of fortifications, including the legendary Theodosian Walls that protected Constantinople for over a thousand years.

Technological innovations such as Greek fire—a mysterious incendiary weapon—gave Byzantium an edge in naval warfare, deterring enemies and protecting its capital from seaborne assaults.

Economic Dynamism and Global Influence

Economically, Byzantium was a powerhouse controlling vital trade routes that connected East and West. Constantinople's bazaars and ports were vibrant centers of commerce, attracting traders from across the ancient world. The empire's industries, including silk production—once a closely guarded secret—glassmaking, and luxury crafts, fueled economic prosperity and cultural expression.

Byzantium’s influence extended far beyond its borders. It shaped the development of Slavic cultures, influenced Islamic art and architecture, and served as a model of imperial governance. Even after its fall, the legacy of Byzantium endured in the laws, religion, art, and diplomacy of Europe and the Near East.

An impostor empire?

The common misconception that the Byzantine Empire was somehow an "impostor" or a diminished remnant of the Roman Empire largely stems from later Western European attitudes, particularly during the Renaissance and after, when the Latin West sought to assert its primacy over the Eastern Orthodox world. Yet, this view distorts the reality of Byzantine self-identity and political legitimacy, which was rooted deeply in the continuity of the Roman tradition.

The Roman Legacy in the East

When Emperor Theodosius I divided the Roman Empire in 395 AD between his two sons, the Western Roman Empire inherited Rome, Italy, Gaul, Hispania, and parts of North Africa, while the Eastern Roman Empire included Greece, Asia Minor, the Levant, Egypt, and the Balkans. Despite this administrative split, there was no question in the minds of the empire’s inhabitants that the Eastern Roman Empire was the direct and legitimate continuation of Rome.

Its citizens called themselves "Romans" (Rhomaioi) and their empire "Romania"—not in the geographical sense but as the "land of the Romans." This identity was not merely a nostalgic claim; it was the very foundation of their political and religious legitimacy. Byzantine emperors continued to use Roman law, minted coins with Latin inscriptions well into the 7th century, and upheld Roman administrative structures even as the Greek language gradually replaced Latin in everyday use.

The Shift from Latin to Greek

The gradual linguistic transition from Latin to Greek in the eastern provinces reflected the demographics and culture of the region rather than a break with Rome. Greek had long been the lingua franca of the Eastern Mediterranean, and over time, Byzantine elites increasingly used Greek for administration, literature, and theology. This transition sometimes gave outsiders the impression of a new or distinct culture emerging, but Byzantines themselves considered this evolution within the Roman tradition.

The survival of the Eastern Empire after the collapse of the West in 476 AD was no accident; it was the result of deliberate and often brilliant governance, military resilience, and religious cohesion. While the Western Empire fragmented under pressure from barbarian invasions, the Eastern Empire adapted, reorganized, and absorbed new populations, maintaining the Roman imperial ideal.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «Литрес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на Литрес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.