полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 290, December 29, 1827

At this period the principal object of attention in the manufacture of gas was its purification. Mr. D. Wilson, of Dublin, took out a patent for purifying coal gas by means of the chemical action of ammoniacal gas. Another plan was devised by Mr. Reuben Phillips, of Exeter, who obtained a patent for the purification of coal gas by the use of dry lime. Mr. G. Holworthy, in 1818, took out a patent for a method of purifying it by causing the gas, in a highly-condensed state, to pass through iron retorts heated to a dark red. For this object and several others, having in view improvements upon the ordinary method, many other patents were procured.

OIL gas now appeared in the field as a rival of COAL gas. In 1815, Mr. John Taylor had obtained a patent for an apparatus for the decomposition of oil and other animal substances; but the circumstance which more particularly attracted the public attention to be directed to oil gas was the erection of the patent apparatus at Apothecary's Hall, by Messrs. Taylors and Martineau; and the way was prepared for an application to parliament for the establishment of an Oil Gas Company by sundry papers in journals, and by the recommendations of Sir William Congreve, who had been employed by the Secretary of State to inspect the state of the gas manufactories in the metropolis. This application, made in the year 1825, proved unfortunate.

In Sir William's Reports is the following account, beginning with the London Gas-Light and Coke Company:—

At the Peter-street station the whole number of the retorts which they had fixed was 300; the greatest number working at any time daring the last year, 22l; the least 87. Fifteen gasometers, varying in dimensions, the contents computed on an average at 20,626 cubic feet each, amounting to 309,385 cubic feet altogether; but never quite filled; the working contents estimated at 18,626 cubic feet each—in the whole at 279,390 cubic feet. The extent of mains belonging to this station is about fifty-seven miles, there being two separate mains in some of the streets; the produce of gas from 10,000 to 12,000 cubic feet from a chaldron of coals. The weekly consumption of coal is reckoned at 42 bushels for each retort, amounting to about 602 chaldrons; and taking the average number of retorts worked at this station at about 153, would give an annual consumption of coals of upwards of 9,282 chaldrons, producing 111,384,000 cubic feet of gas.

The average number of lights during the year 1822 was 10,660 private, 2,248 street lamps, theatres, 3,894.

At the Brick-lane works, the number of retorts which were fixed was 371, the greatest number worked 217, and the least 60. The number of gasometers 12, each averaging 18,427 cubic feet, amounting in the whole to 221,131 cubic feet; and their average working contents 197,124 cubic feet. The average number of retorts worked was 133; the coals consumed 8,060 chaldrons; the quantity of gas produced 96,720.000 cubic feet; the number of lamps 1,978 public, 7,366 private, through 40 miles of mains.

At the Curtain-road establishment the whole number of retorts was 240; the greatest number worked in the last year 80; the lowest 21. The number of gasometers 6, average contents of each 15,077 cubic feet; the contents of the whole 90,467; another gasometer containing 16,655 cubic feet; the average number of retorts worked 55; the coals consumed 3,336 chaldrons; quantity of gas produced 40,040,000 cubic feet; the number of lamps supplied 3,860 private, and 629 public, through 25 miles of mains.

The whole annual consumption of coals by the three different stations was 20,678; the quantity of gas produced 248,000,000 cubic feet: the whole number of lamps lighted by this company 30,735, through 122 miles of mains.

The City of London Gas-Light Company, Dorset-street:—The number of retorts fixed 230; the number of gasometers 6; the largest 39,270 cubic feet, the smallest 5,428 cubic feet; two large additional gasometers nearly completed, contents of each 27,030 cubic feet, making in the whole 181,282 cubic feet. The number of lamps lighted 5,423 private, and 2,413 public, through 50 miles of mains. The greatest number of retorts worked at a time (in 1811) 130, the least 110, average 170. The quantity of coals carbonized amounted to 8,840 chaldrons; produced 106,080,000 cubic feet of gas.

The South London Gas-Light and Coke Company, at Bankside:—The number of retorts was 140; gasometers 3; the contents of the whole 41,110 cubic feet; and their mains from 30 to 40 miles in length. At their other station in Wellington-street, they had then no retorts in action; but three large gasometers were erected, containing together 73,565 cubic feet, which were supplied from Bankside till the retorts were ready to work.

The Imperial Gas-Light and Coke Company were erecting at their Hackney station two gasometers of 10,000 cubic feet each, and about to erect four more of the same size. At their Pancras station they had marked out ground for six gasometers of 10,000 cubic feet each.

In the year 1814, there was only one gasometer in Peter-street, of 14,000 cubic feet, belonging to the Chartered Gas-Light Company, then the only company established in London. At present there are four great companies, having altogether 47 gasometers at work, capable of containing in the whole 917,940 cubic feet of gas, supplied by 1,315 retorts, and these consuming 33,000 chaldron of coals in the year, and producing 41,000 chaldron of coke. The whole quantity of gas generated annually being upwards of 397,000,000 cubic feet, by which 61,203 private, and 7,268 public or street lamps are lighted in the metropolis. In addition to these great companies, there are several private companies, whose operations are not included in the foregoing statements.—Abridged from Matthews's History of Gas-Lighting, and the London Magazine, Dec. 1827.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

LONDON LYRICS

MAGOG'S PROPHECYPastor cum traheret per freta navibus.HOR. lib. i. od. 15.As late, of civic glory vain,The Lord Mayor drove down Mincing-lane,The progress of the baimer'd trainTo lengthen, not to shorten:Gigantic Magog, vex'd with heat,Thus to be made the rabble's treat,Check'd the long march in Tower-street,To tell his Lordship's fortune."Go, man thy barge for Whitehall Stair;Salute th' Exchequer Barons there,Then summon round thy civic chairTo dinner Whigs and Tories—Bid Dukes and Earls thy hustings climb;But mark my work, Matthias Prime,Ere the tenth hour the scythe of TimeShall amputate, thy glories."Alas! what loads of food I see,What Turbots from the Zuyder Zee,What Calipash, what Calipee,What Salad and what Mustard:Heads of the Church and limbs of Law,Vendors of Calico and Straw,Extend one sympathetic jawTo swallow Cake and Custard."Thine armour'd Knights their steeds discard'To quaff thy wine 'through helmet barr'd,'While K.C.B.'s, with bosoms starr'd,Within their circle wedge thee.Even now I see thee standing up,Raise to thy lip 'the loving cup,'Intent its ruby tide to sup,And bid thy hearers pledge thee."But, ah! how fleeting thy renown!Thus treading on the heel of Brown;How vain thy spangled suit, thy gownIntended for three waiters:Ere Lansdowne's speech is at an end,I see a board of lamps descend,Whose orbs in bright confusion blend,And strew the floor with splinters."Their smooth contents spread far and near,And in one tide impetuous smearKnight, Waiter, Liveryman, and Peer:Nay, even his Royal HighnessThe falling board no longer props,Owns, with amaze, the unwelcome dropsAnd, premature anointment, swapsFor oozy wet his dryness."Fear shrieks in many a varied tone,Pale Beauty mourns her spotted zone,And heads and bleeding knuckles ownThe glittering prostration.Behold! thou wip'st thy crimson chin,And all is discord, all is din;While scalded waiters swear thee inWith many an execration."Yet, Lucas, smile in Fortune's spite;Dark mornings often change to bright;Ne'er shall this omen harm a wightSo active and so clever.How buoyant, how elastic thou!With a lamp halo round thy brow,Prophetic Magog dubs thee nowA Lighter man—than ever."New Monthly MagazineROYAL APPETITES

Charles XII. was brave, noble, generous, and disinterested,—a complete hero, in fact, and a regular fire-eater. Yet, in spite of these qualifications and the eulogiums of his biographer, it is pretty evident to those who impartially consider the career of this potentate, that he was by no means of a sane mind. In short, to speak plainly, he was mad, and deserved a strait-waistcoat as richly as any straw-crowned monarch in Bedlam. A single instance, in my opinion, fully substantiates this. I allude to his absurd freak at Frederickshall, when, in order to discover how long he could exist without nourishment, he abstained from all kinds of food for more than seventy hours! Now, would any man in his senses have done this? Would Louis XVIII., for instance, that wise and ever-to-be-lamented monarch? Had it been the reverse indeed—had Charles, instead of practising starvation, adopted the opposite expedient, and endeavoured to ascertain the greatest possible quantity of meat, fruit, bread, wine, vegetables, Sec. &c. he could have disposed of in any given time—why then it might have been something! But to fast for three days! if this be not madness—! Indeed, there is but one reason I could ever conceive for a person not eating; and that is, when, like poor Count Ugolino and his family, he can get nothing to eat!

Charles, now, and Louis—what a contrast! The first despised the pleasures of the table, abjured wine, and would, I dare say, just as soon have been without "a distinguishing taste" as with it. Your Bourbon, on the contrary, a five-mealed man, quaffing right Falernian night and day; and wisely esteeming the gratification of his palate of such importance, as absolutely to send from Lisle to Paris—distance of I know not how many score leagues—at a crisis, too, of peculiar difficulty—for a single pâte! "Go," cried the illustrious exile to his messenger; "dispatch, mon enfant! Mount the tricolor! Shout Vive le Diable! Any thing! But be sure you clutch the precious compound! Napoleon has driven me from my throne; but he cannot deprive me of my appetite!" Here was courage! I challenge the most enthusiastic admirer of Charles to produce a similar instance of indifference to danger!

There is another trait in the character of Louis which equally demands our admiration, and proves that the indomitable firmness may be sometimes associated with the most sensitive and—I had almost said—infantine sensibility. Of course, it will be perceived that I allude to the peculiar tenderness by which that amiable prince was often betrayed, even into tears, upon occasions when ordinary minds would have manifested comparative nonchalance. I have been assured that Louis absolutely wept once at Hartwell, merely because oysters were out of season!—a testaceous production, to which he was remarkably attached, (whence his cognomen of Des Huîtres, by corruption Dix-huit;) so much so, indeed, as to be literally ready to eat them, whenever they were brought into his presence. It is said that this worthy descendant of the Good Henrí used to put a barrel of Colchester oysters daily hors de combat, merely to give him an appetite.

Monthly MagazinePORSON AND SHERIDAIT

The worst effect of "the scholar's melancholy," is when it leads a man, from a distrust of himself, to seek for low company, or to forget it by matching below himself. Porson, from not liking the restraints, or not possessing the exterior recommendations of good society, addicted himself to the lowest indulgences, spent his days and nights in cider-cellars and pot-houses, cared not with whom or where he was, so that he had somebody to talk to and something to drink, "from humble porter to imperial tokay," (a liquid, according to his own pun,) and fell a martyr, in all likelihood, to what in the first instance was pure mauvaise honte. Nothing could overcome this propensity to low society and sotting, but the having something to do, which required his whole attention and faculties; and then he shut himself up for weeks together in his chambers, or at the university, to collate old manuscripts, or edite a Greek tragedy, or expose a grave pedant, without seeing a single boon companion, or touching a glass of wine. I saw him once at the London Institution with a large patch of coarse brown paper on his nose, the skirts of his rusty black coat hung with cob-webs, and talking in a tone of suavity approaching to condescension to one of the managers. It is a pity that men should so lose themselves from a certain awkwardness and rusticity at the outset. But did not Sheridan make the same melancholy ending, and run the same fatal career, though in a higher and more brilliant circle? He did; and though not from exactly the same cause, (for no one could accuse Sheridan's purple nose and flashing eye of a bashfulness—"modest as morning when she coldly eyes the youthful Phoebus!") yet it was perhaps from one nearly allied to it, namely, the want of that noble independence and confidence in its own resources which should distinguish genius, and the dangerous ambition to get sponsors and vouchers for it in persons of rank and fashion. The affectation of the society of lords is as mean and low-minded as the love of that of cobblers and tapsters. It is that cobblers and tapsters may admire, that we wish to be seen in the company of their betters.

New Monthly MagazineTHE "STAY-AT-HOME."

I'll never dwell among the Caffres;I'll never willing cross the Line,Where Neptune, 'mid the tarry laughers,Dips broiling landsmen in the brine.I'll never go to New South Wales,Nor hunt for glory at the Pole—To feed the sharks, or catch the whales,Or tempt a Lapland lady's soul.I'll never willing stir an ellBeyond old England's chalky border,To steal or smuggle, buy or sell,To drink cheap wine, or beg an Order.Let those do so who long for claret,Let those, who'd kiss a Frenchman's—toes;I'll not drink vinegar, nor Star it,For any he that wears a nose.I'll not go lounge out life in Calais,To dine at half a franc a head;To hut like rats in lanes and alleys—To eat an exile's gritty bread.To flirt with shoeless Seraphinas,To shrink at every ruffian's shako;Without a pair of shirts between us,Morn, noon, and night to smell tobacco;To live my days in Gallic hovels,Untouched by water since the flood;To wade through streets, where famine grovelsIn hunger, frippery, and mud.Monthly MagazineTHE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

ART OF DRINKING WINE

The order of taking wine at dinner has not been sufficiently observed in this country. "There is," as the immortal bard beautifully expresses it, "a reason in roasting eggs;" and if there is a rationale of eating, why should there not be a system of drinking? The red wines should always precede the white, except in the case of a French dinner, when the oysters should have a libation of Chablis, or Sauterne. I do not approve of white Hermitage with oysters. The Burgundies should follow—the purple Chambertin or odorous Romanee. A single glass of Champagne or Hock, or any other white wine, may then intervene between the Cote Rotie and Hermitage; and last, not least in our dear love, should come the cool and sweet-scented Claret. With the creams and the ices should come the Malaga, Rivesaltes, or Grenache; nor with these will Sherry or Madeira harmonize ill. Last of all, should Champagne boil up in argent foam, and be sanctified by an offering of Tokay, poured from a glass so small, that you might fancy it formed of diamond.

Literary Pocket-BookSTRATFORD-ON-AVON

I was detained at Stratford nearly two hours, and endeavoured to see whatever I could, in so short a time, relative to Shakspeare. The clean, quiet, uncommercial appearance of the town pleased me; but I was interested beyond expression on seeing the great poet's house. When I entered the untenanted room where he first drew the breath of this world, I took off my hat with, I hope, an unaffected sentiment of homage. The walls and ceiling of this chamber are covered with names and votive inscriptions, among which I saw the signatures of Sir Walter Scott, Mr. Lockhaft, Washington Irving, and many others familiar to me, foreigners as well as English. I did not sign my name, for I felt that it had no right in such a place; but I brought away a minute relic, in the shape of a bit of rotten wood, pinched from the beam that supports the chimney.

From the birth-place of the illustrious man, I found my way to his corpse-place; and never had I beheld so beautiful and venerable a church, or so tranquil and lovely a spot. The approach to the edifice, which is situated at some distance from the town, upon the banks of the fresh and murmuring Avon, is through an avenue of lime-trees, the branches of which are interlaced archwise, as Lord Bacon would say, so as to form a green canopy of some length. The scenery is not what is called romantic, but soft and quiet, and calculated, above all things, to surround the tomb of the genial poet of human nature.

I was determined to get into the church, though it was so early; and, accordingly, after a little trouble, I found out the sexton, a fine old fellow, with a Saxon name, who was munching his breakfast in a large old-fashioned room with latticed casements, half kitchen and half parlour. But he was too busy with his meal to be disturbed; and accordingly he sent his wife with me to open the church, and I believe our footsteps were the first which had that morning disturbed the holy silence of the place. The building is very fine, and even stately; but the interest connected with Shakspeare absorbs all other feelings, and monopolizes one's admiration. I stood under his monument, on the very stone of his grave. * * *

IbidTHE GATHERER

"I am but a Gatherer and disposer of other men's stuff."—Wotton.LORD RUSSEL

When my Lord Russel was on the scaffold, and preparing to be beheaded, he took his watch out of his pocket and gave it to Dr. Burnet, who assisted his devotions, with this observation: "My time-piece may be of service to you: I have no further occasion for it. My thoughts are fixed on eternity."

EPITAPH ON A SCOLD

Here lies my wife; and heaven knows,Not less for mine than her repose!ON A MAN WHOSE NAME WAS PENNY

Reader, if in cash thou art in want of any,Dig four feet deep and thou shalt find A PENNY.DRAMATIC SKETCH OF A THIN MAN

A long lean man, with all his limbs rambling—no way to reduce him to compass, unless you could double him like a pocket rule—with his arms spread, he'd lie on the bed of Ware like a cross on a Good Friday bun—standing still, he is a pilaster without a base—he appears rolled out or run up against a wall—so thin that his front face is but the moiety of a profile—if he stands cross-legged, he looks like a Caduceus, and put him in a fencing attitude, you would take him for a piece of chevaux-de-frise—to make any use of him, it must be as a spontoon or a fishing-rod—when his wife's by, he follows like a note of admiration—see them together, one's a mast and the other all hulk—she's a dome, and he's built together like a glass-house—when they part, you wonder to see the steeple separate from the chancel, and were they to embrace, he must hang round her neck like a skein of thread on a lace-maker's bolster—to sing her praise, you should choose a rondeau; and to celebrate him, you must write all Alexandrines.—Sheridan's MSS. in Moore's Life of him.

A man of words and not of deeds,Is like a garden full of seeds.STOLEN GOODS

A Negro in Jamaica was tried for theft, and ordered to be flogged. He begged to be heard, which being granted, he asked—"If white man buy tolen goods why he be no flogged too?" "Well," said the judge, "so he would." "Dere, den," replied Mungo, "is my Massa, he buy tolen goods, he knew me tolen, and yet he buy me."—Elgin Courier.

DECREASE OF LUNACY IN LONDON

According to the Parliamentary Returns in May, 1819, the total number of lunatics comprised in the circle of London and different private asylums, amounted to 2,005, which Dr. Burrows calculates as proving an increase of only five on an average in twenty years, notwithstanding the increase of our population. The late Dr. Heberden and Dr. Willan both concurred in this statement. The large district of Mary-la-bonne, which some years ago comprehended the greatest proportion of inhabitants in the metropolis, not less than 80,000,—from 1814 to the year 1819 received only 180 female lunatics, and 118 males.

INGREDIENTS OF MODERN LOVE

Twenty glances, twenty tears,Twenty hopes, and twenty fears,Twenty times assail your door,And if denied, come twenty more,Twenty letters perfumed sweet,Twenty nods in every street,Twenty oaths, and twenty lies,Twenty smiles, and twenty sighs,Twenty times in jealous rage,Twenty beauties to engage,Twenty tales to whisper low,Twenty billet-doux to show,Twenty times a day to pass,Before a flattering looking-glass,Twenty times to stop your coach,With twenty words of fond reproach,Twenty days of keen vexation,Twenty opera assignations,Twenty nights behind the scenes,To dangle after mimic queens,Twenty such lovers may be found,Sighing for twenty thousand pounds,But take my word, ye girls of sense,You'll find them not worth twenty-pence.GREAT AND SMALL

A shopkeeper at Poncaster had, for his virtues, obtained the name of the little rascal. A stranger asked him why this application was given him? "To distinguish me from the rest of my trade," quoth he, "who are all great rascals."

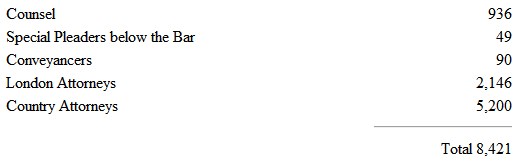

C.F.ETHE LAW, PROFESSORS OF, IN ENGLAND:—

EPIGRAM FROM THE SPANISH OF REBOLLEDO

(For the Mirror.)Fair Phillis has fifty times registered vows,That of Christian or Turk, she would ne'er be the spouse,For wedlock so much she disdain'd,And neither of these she has married, 'tis true,For now she's the wife of a wealthy old Jew;And thus she her vow has maintain'd!E.L.JTHE LAWYER AND HIS CLIENT

Two lawyers, when a knotty cause was o'er,Shook hands and were as good friends as before,"Zounds!" says the losing client, "how come yawTo be such friends, who were such foes just naw?""Thou fool," says one, "we lawyers tho' so keen,Like shears, ne'er cut ourselves, but what's between."LIMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE

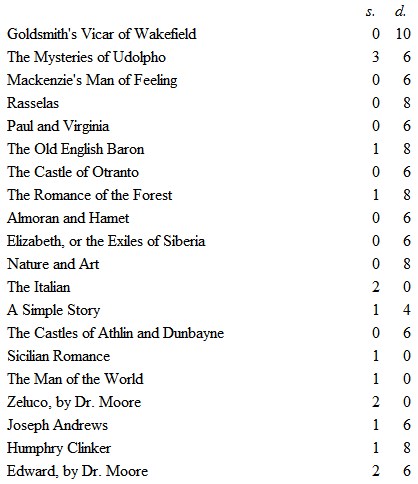

BRITISH NOVELIST, Publishing in Monthly Parts, price 6d. each.—Each Novel will be complete in itself, and may be purchased separately.

The following Novels are already Published:

1

"Ancient Wilts,"–Sir R.C. Hoare, speaking of Stonehenge, expresses his opinion that "our earliest inhabitants were Celts, who naturally introduced with them their own buildings customs, rites, and religions ceremonies, and to them I attribute the erection of Stonehenge, and the greater part of the sepulchral memorials that still continue to render its environs so truly interesting to the antiquary and historian." Abury, or Avebury, is a village amidst the remains of an immense temple, which for magnificence and extent is supposed to have exceeded the more celebrated fabric of Stonehenge; Some enthusiastic inquirers have however, carried their supposition beyond probability, and in their zeal have even supposed them to be antediluvian labours! Many of the barrows in the vicinity of Sarum have been opened, and in them several antiquarian relics have been discovered. In short, the whole county is one of high antiquarian interest, and its history has been illustrated with due fidelity and research.