Полная версия

As long as I remember you

As long as I remember you

Madina Fedosova

© Madina Fedosova, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0068-1772-2

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

Author’s Preface

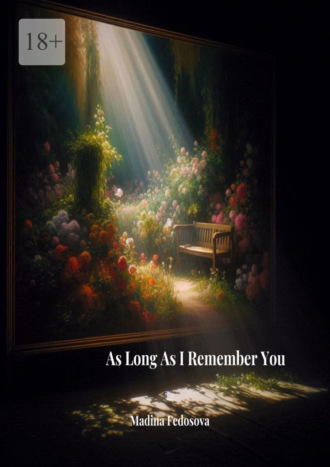

This book was born from darkness.

When I was nineteen, the world I knew collapsed. It didn’t shatter in an instant – it began to slowly, inexorably dissolve, losing its color and sound, slipping through my fingers along with my memory. At first, there were only warning signs: dizzy spells I blamed on fatigue, headaches that seemed like mere nuisances on the path of everyday life.

But soon, the nuisance became a wall. The wall turned into a labyrinth from which I believed there was no escape. Navigating it was terrifying. Vague diagnoses were replaced by one that was clear and cold as a blade. My world shrank to the size of a hospital room, to the circle of light I could still make out, while everything else drowned in darkness. I began to lose my sight, my hearing, my strength. I forgot what happened yesterday. My future, once so bright and promising, narrowed to the next IV drip, the next pill, the next injection.

The words of doctors and acquaintances – «many people die from this,» «it’s rare at your age, but it happens» – hung in the air like a heavy, suffocating bell. Thoughts of impending death were not abstract philosophy – they were concrete and physically palpable. They were the chilling terror at three in the morning, when you feel utterly alone facing an infinite, silent void.

I prayed. I wept. I despaired. And I hoped. Cycles of flare-ups and remissions stretched over two long years. Life turned to shifting sand: today you can almost walk, tomorrow you can’t lift your head from the pillow.

But this story is not about illness. And it is certainly not about defeat.

This story is about the light we find in the deepest darkness. About the beauty we can see even when our eyes are failing. About the love that becomes our anchor, our voice, our memory, and our hands when our own betray us.

Amelia is not me. Her story and her path are different. But the darkness she walks through is chillingly familiar to me. The despair that whispers for her to give up – I have heard its whisper. And the strength that compels her to pick up a brush and leave her mark – that is the very strength that made me fight.

I wrote this book as a reminder. To myself and to anyone who might find themselves in their own labyrinth.

A reminder that even the most difficult struggle is itself a victory. That every painful day is still a day of life. That our worth is measured not by our achievements, but by the depth of our feelings, the sincerity of our love, and the courage with which we face our dawn, even knowing sunset will follow.

I found my way out. I am healthy now, and every new day is a priceless gift. And I believe that a fragment of the strength that helped me lives on these pages.

If this book finds someone who is struggling, who is afraid, who feels alone in their fight – then it has fulfilled its purpose.

You are not alone. And as long as you are breathing, you are writing your story. May it be filled with the light you can find even within yourself.

With faith in your strength,

Madina Fedosova

Part One

The Garden’s Dawn

Chapter 1

Endless Summer

The sun in Kent in July is not just a celestial body; it is the undisputed master of the world. It floods everything with a generous, thick, almost tangible light, transforming the most mundane things into something magical. Long shadows from old, sprawling oaks lay crisp silhouettes on the ground, and the air shimmers with heat, filled with the chorus of cicadas, their monotonous chirring the soundtrack to this perfect day.

Amelia was running along the edge of a lavender field, and she felt as if she were flying. The warm, sun-cracked earth sprang softly beneath her bare feet, and countless purple blossoms brushed against her palms, leaving an intoxicating, spicy scent on her skin. It was everywhere – in the air she breathed deeply, on her lips, in the strands of hair escaping her loose bun. She was twenty-seven, and her whole life lay before her, like this endless, purple sea stretching to the horizon. She felt every muscle of her strong, young body, every breath, every jubilant beat of her heart – fast as the flutter of a hummingbird’s wings.

She slowed her pace, threw her head back, and spun in place, arms outstretched, letting the sun flood her face with liquid gold and the world turn into a dazzling, fragrant kaleidoscope of blue sky, emerald green, and lilac waves.

«You look like that girl from The Sound of Music,» came a beloved, slightly mocking voice from behind, pulling her from the heavens back to earth. «Only instead of the Alps, it’s a farm in Kent, and instead of a meadow, it’s lavender!»

She stopped, breathless, her wind-tousled hair the color of ripe wheat, and turned. Luca was standing at the edge of the field, leaning against an old, time-weathered wooden gate. He was swinging her delicate summer sandals, which she’d kicked off by the car the moment she saw this purple splendor. He looked at her with that smile that made his stern, Eastern European features – high cheekbones, a straight nose, a serious brow – incredibly soft and young.

«And what, isn’t this better?» she laughed, running up to him, feeling the earth’s energy surge beneath her soles. «It smells a million times more interesting! The Alps smell of snow and altitude, but here… here it smells of happiness. Real, simple, earthly happiness. Of sun, honey, dust, and lavender. I can smell it, and one day, maybe I can even paint it. Transfer the very scent onto a canvas.»

«Smells like tourists and expensive lavender soap from souvenir shops,» he retorted, but his laughing eyes betrayed his deep enjoyment of the moment.

«Ugh, you’re such a cynic and a snob!» She playfully shoved his shoulder, took her sandals from him, but didn’t put them on. «You, a man of letters, should understand! It’s all about metaphors and sensations. You just don’t know how to feel the moment, to dissolve in it. Right here, right now, Luca. Close your eyes.»

He obediently squeezed his eyes shut, lifting his face to the sun, and for a moment she admired him: so solid and so vulnerable at once.

«And what am I supposed to feel? Besides my eyelids turning transparent and everything being red?»

«Everything!» She took a deep breath, closing her own eyes to guide him. «Do you hear? The bees are buzzing. There are thousands of them, each busy with its important work. A hawk is crying somewhere far beyond the hill. And the wind… it’s whispering something of its own, murmuring to every flower, every stalk. And the sun… it’s not just shining. It’s warm, heavy, like slow, thick syrup. You can almost touch it. I want to remember this. Every last grain of sand, every last speck of dust in the air. So that one day… I can paint it. Not a picture. But the very feeling of this day. This field. Us being here. So that anyone who looks at it will feel this… this aching, piercing happiness – just to be alive and to be here.»

She opened her eyes and saw he was no longer looking at her with mockery, but with that deep, attentive expression he usually had when reading a truly brilliant manuscript. The look of a man who had seen a whole universe in a single dewdrop.

«You will,» he said simply and firmly, without a trace of doubt. «You’ll be able to transfer even the wind and the scent onto a canvas. I haven’t a single doubt. That is your gift, Amelia. You don’t just see the world, you feel it. And you make others feel it, too.»

They found a secluded spot under a sprawling, solitary apple tree at the edge of the field, from which the first, still green but juice-swollen apples were beginning to fall. They sat on the ground, leaning their backs against the rough, sun-warmed bark. Amelia ran her fingers through the thick, cool grass, feeling its resilience and vitality. An unseen bird chirped in the branches above.

«You know what I’m thinking about right now?» she asked quietly, watching the shadows from the leaves dance on his sun-tanned knees.

«About how to convince me to buy you the entire assortment from that soap shop, so our whole apartment will smell of this field for months?» he suggested, stretching his stiff leg.

«No,» she smiled and leaned her shoulder against his. «I’m thinking about the future. Ours. One just like this… only more, fuller, deeper.»

She paused, gathering her thoughts, trying to put into words the vast, warm, almost overwhelming feeling that filled her.

«I imagine a house. Not in central London, with the hum of cars and streetlights at night. Somewhere here, in the countryside, or in Suffolk, or in Cornwall by the ocean. With big, floor-to-ceiling windows where lilac bushes peek in, and a real garden. Not just flowerbeds, but a proper, large garden where you could get lost. And our children running in that garden. Two. A boy and a girl.»

She spoke, and the picture came alive before her, so vivid and real it made her heart clench with tenderness and a light, tickling fear.

«The girl is just like me, stubborn, with a face forever smudged with paint or dirt, perpetually tangled hair, and a paintbrush in her hand instead of a pacifier. And the boy is your copy, serious, in glasses, with a book under his arm by the age of five. He’ll always be running after her, lecturing her.»

She fell silent to listen to the cicadas and feel his hand cover hers.

«And you and I will sit just like this, on the porch, drinking evening tea with mint from our garden, watching them race across the lawn as the sun sets and bathes everything in that same golden light. You’ll read me something new, something brilliant and unknown you’ve dug up from a pile of manuscripts. And I’ll be sketching. Not for an exhibition, not for sale. Just to capture that moment. That perfect, ordinary, most important moment of our lives. Isn’t it beautiful? Isn’t it worth living for?»

Luca put his arm around her shoulders and pulled her close. She pressed her cheek to his chest, listening to the steady, calm beat of his heart beneath the thin cotton of his shirt.

«It’s perfect,» his voice was quiet and deep, as if coming from his very core. «As if you read my most secret thoughts. Only in my version, the boy will still play football and get his glasses dirty, not just read books. And the girl… let her be exactly like you. Invincible, beautiful, and made entirely of colors and wind.»

They sat in silence, listening to the rustle of leaves overhead, the tireless buzzing of bees in the lavender, the distant lowing of acow from the other side of the hill. The world hung suspended in a golden-purple haze of noon, frozen in its perfection.

«All of life really is ahead of us,» Amelia whispered, closing her eyes and feeling the warmth of his body merge with the warmth of the sun. «It feels like we can do absolutely everything. Fame, recognition, that porch, the sound of children’s laughter in the garden… There’s so much of it, and it all feels so possible. So close. Within reach. You just have to be brave enough to reach out and take it.»

«We will,» Luca said confidently, kissing the top of her head, her hair most golden from the sun. «We’re only at the beginning of the path, sunshine. This is our endless summer, Amelia. It’s only just begun.»

She believed him. As unquestioningly as she believed the sun would rise tomorrow morning. She smiled, peering into the distance where the purple field merged with the blurred line of the horizon. She saw her future there – bright, sharp, detailed like her best paintings, infinitely long and happy.

She couldn’t know that this very «endless summer» had already come to an end, even as it was just beginning. She didn’t feel how, deep inside, in the most hidden, invisible corners of her brain, the seed of that quiet, merciless winter had already sprouted and sent out its first, relentless roots. And that this perfect, meticulously rendered day would become her greatest treasure and her cruelest memory. The very picture she would try to paint again and again, no longer smelling the lavender or seeing the color purple, when the world around her began to slowly, irreversibly, and inexorably fade.

We think we are losing memories, but in truth, we are losing ourselves. Piece by piece. Until only silence remains – this thought, alien and bitter, flickered somewhere in the back of her mind and then evaporated, washed away by the triumphant voice of the cicadas and the warmth of her beloved’s hand.

Chapter 2The First CrackReturning to London after two days in their Kentish paradise was like plunging into cool, murky water after the bright sun. The contrast was felt in every cell. Instead of the deafening silence, filled only with the buzzing of bees and the whisper of the wind, there was the intrusive, low-frequency hum of the metropolis, composed of the honks of black cabs, the distant rumble of the underground, ambulance sirens somewhere on the Victoria Embankment, and the perpetual sound of tires on rain-damp asphalt. Instead of the intoxicating scent of lavender and sun-warmed pine, there was the complex, layered bouquet of London: the smell of wet stone from old buildings, the sweetish smoke from chimneys in wealthy quarters, the bitter aroma of aged wood from pubs, the scent of freshly cut flowers from a stall at the tube entrance, and the ever-present smell, especially in the mornings, of fresh pastries and fried bacon.

Amelia stood by the large window of her third-floor studio, watching people scurry along the street below like colorful brushstrokes on a gray canvas. In her hand, she clutched a tube of paint as if it were an amulet connecting her to that bygone happiness. The images from the lavender field were still bright, almost tangible: the warmth of Luca’s back under the apple tree, the taste of the strawberries they bought from a roadside stall, the feeling of utter, complete peace.

With a greed born of fear that the memory would fade like an old photograph, she seized her brushes. She didn’t start on a large canvas right away – first, she needed to capture the mood, make quick, impulsive sketches, fix the movement, the play of light, that very «sensation.»

She decided to start with color. With that specific, complex, living purple that she saw not as a pure pigment but as a mixture of a thousand shades: the hazy blue on the horizon, the golden highlights on the buds, the deep shadow under the leaves. She took a heavy wooden palette, placed it in its usual spot by her elbow, squeezed out a drop of ultramarine, added some thick, jam-like alizarin crimson, a pinch of white…

And then it happened.

The fingers of her right hand, which had just been firmly holding the palette knife, suddenly went strangely weak. It wasn’t just numbness – it felt as if her hand had suddenly fallen asleep, but only the skin, the very top layer. Her fingertips became cottony, alien, unable to feel the texture of the wooden handle. The tool slipped from her weakened grip, fell onto the palette with a dull thud, smearing the freshly mixed paint, and then clattered to the floor.

«Damn it!» she exclaimed, more in annoyance than fear. She began vigorously rubbing her fingers, pinching them. The numbness gradually receded, replaced by an unpleasant, prickling sensation, as if her hand had been pinned. «Circulation,» she told herself sternly. «I need to stretch more. I’ve been working in the same position for too long.»

She bent down to pick up the palette knife, and her gaze fell on a freshly squeezed, untouched drop of cobalt blue. Bright, perfectly round, thick.

And then the world tilted.

The color moved. No, it wasn’t like a fleeting illusion in the field. This was something physical, frightening. The blue drop suddenly began to pulsate, like a living, trembling heart. Its edges blurred and contracted, but with each beat it grew brighter, more intense, turning into a tiny, blinding blue sun ready to burn her retina. Waves radiated from it, distorting space – the wood of the palette swam, her own fingers seemed distant and alien, the labels on the paint tubes blurred into unreadable smudges. A sharp pain lanced behind her eyes, a dull, throbbing ache pounded in her temples.

Amelia squeezed her eyes shut, pushing herself away from the table so forcefully she nearly knocked over the easel with its unfinished sketch. She stood with her back against the cold wall, breathing in quick, shallow gasps, as if after a sprint. Her heart hammered wildly in her throat. A wave of pure, animal fear washed over her, constricting her throat, then slowly receded, leaving behind an icy emptiness and utter, deafening bewilderment.

When she opened her eyes again, afraid to see the nightmare continue, everything was in its place. The palette. The paints. The palette knife on the floor. No pulsation. Only the drop of cobalt stared back at her with its usual, clear, and calm color.

«Overwork,» she whispered, and her voice sounded hoarse and unconvincing even to her own ears. «Nerves. I need to distract myself. I absolutely must distract myself.»

She poured herself a large mug of strong Earl Grey tea – a drink she always associated with comfort and safety – trying not to look at the palette, and went out onto the small balcony crowded with geranium pots. London lived its irrepressible life. A bright red double-decker bus hissed past on the cobblestones below, its wheel-spray glittering in the suddenly emerged sun. Pedestrians hurried about their business, turning up their coat collars against the sharp, gusty wind from the Thames. A woman in an elegant trench coat was holding the hand of a little girl in bright yellow rubber boots. Everything was normal. Mundane. Real.

But something inside her had fractured. That unconditional, childlike faith in the world’s infinity and reliability had developed its first, ominous crack.

That evening, familiar footsteps sounded on the stairs – firm, quick, confident. Luca was home. She heard him fumbling with the keys in the lock, taking off his coat, hanging it up. His arrival always brought a particular, chaos-ordering soundscape into the space.

«I’m home!» his voice came from the hallway. «And I bring sensational news and possibly the best wine from the corner shop!»

She was standing by the stove, making Bolognese sauce – his favorite. The smell of garlic fried in olive oil mingled with the aroma of basil and tomatoes. She was trying to cling to these familiar, domestic smells like an anchor.

He walked into the kitchen, energetic, a little excited from a successful day. He was wearing that gray cardigan she loved so much.

«So, sunshine? Did you manage to catch that Kentish rabbit by the tail and put it on a canvas?» he asked, embracing her from behind and kissing that spot on her neck where her blood pulsed.

His touch was so familiar, so dear, that treacherous tears welled in her eyes. She pulled away under the pretext of needing to stir the sauce, and her hand betrayed her again with a tremor as she reached for the jar of oregano. The glass jar slipped from her fingers and clattered against the edge of the sink, fortunately not breaking.

«Careful!» he caught the jar. «Lost in creative agony? Or just starving beyond reason?»

«Yes… just sketching,» she replied, turning away too quickly to the pot of boiling pasta water. Her voice sounded unnaturally high. «Not going well. I can’t capture the right light. It feels like it’s slipping away.»

He sensed something. His perceptiveness, which she usually adored, was now unbearable. He leaned against the kitchen table, watching her.

«Don’t rush. You’re the one who taught me that art is a marathon, not a sprint. It can’t be hurried. Let it settle. Remember how you painted that still life with the pear – you did sketches for it for almost a month.»

«I know, it’s just…» she fell silent, not knowing what to say.

At dinner, he was animated, talking about his day. About securing a good contract for a young writer from Edinburgh, whose novel about a lonely watchmaker he considered a future bestseller. About a funny incident on the tube, when a woman tried to bring a huge bust of Nefertiti into the carriage. He talked, and she nodded, smiled, but caught herself studying his face with a new, greedy, almost painful intensity. Every laugh line around his eyes, every strand of hair at his temple, the play of light and shadow on his cheekbones. She was trying to imprint it in her memory, to make a mental sketch, as if afraid that one day this image would fade, would blur.

«…and he said it wasn’t a metaphor, he actually collects irons!» Luca finished his story and looked at her. His smile gradually faded. «Are you sure you’re alright, Amelia? You seem… absent. As if you’re not really here. Tired?»

He’d noticed. A chill ran down her spine.

«Yes, just a bit dizzy,» she took a sip of water to hide the trembling in her hands. «Must be the fumes from the paint and turpentine. And my fingers… they keep going a bit numb from work. Probably a pinched nerve. Or I just need a break. Spending too much time in the studio.»

He looked at her carefully, and a shadow of the worry she feared to see flickered in his eyes. But, as always, he tried to channel it into a rational, safe direction. He caught himself and smiled, reaching across the table to place his hand over hers.

«Of course, it’s time. Our weekend in Kent wasn’t a rest, just a change of one activity for another. So tomorrow – sabotage. No paintbrushes. What do you say? We’ll go to the National Gallery? Then we can stop by that old bookshop on Charing Cross Road you love. Or just walk in Hyde Park, watch the ducks.»

«The Gallery,» she agreed quickly, squeezing his fingers with such force that he raised an eyebrow in surprise. Going to the gallery meant being in a world of colors, lines, light, and shadow. Her world. To check if it was still intact. To see if the blue robes in Tintoretto’s paintings or the red cloaks in van Dyck’s would suddenly start to pulsate.

«Then it’s settled,» he smiled, stroking her hand. «The Gallery, books, and maybe a giant portion of ice cream. Like proper tourists.»

That night, she woke from a strange, unpleasant sensation. The bedroom was plunged into a deep, almost velvety darkness, broken only by the faint glow of streetlights on the ceiling and Luca’s steady, calm breathing beside her. But her right hand, the one that held the brush, felt alien. Dead, heavy, stiff, insensate. She struggled to wiggle her fingers in the dark, and again, those nasty, prickling pins and needles ran through them, stronger and more persistent this time. A cold terror, quiet and clammy, crept up her spine. This no longer felt like fatigue. It felt like the beginning of something irreversible.

Carefully, trying not to wake Luca, she slipped out of bed. Her bare feet sank into the soft pile of the carpet. She went to the large window overlooking the narrow street and drew back the heavy linen curtains. Night-time London shone with thousands of lights. Somewhere far away, on the roof of a modern building, a neon sign flickered, and its aggressively red light, reflected in puddles on the roof of the neighboring Victorian house, suddenly seemed unnaturally bright, poisonous, almost bloody. It hurt her eyes.

She pressed her forehead against the cold, almost icy glass, trying to quell the fine tremor that had suddenly run through her whole body. Beyond the glass was her city. Her life. Her love was sleeping a few steps away. But between her and all of it, an invisible, glass wall had suddenly risen.

Memory is not a storage room, it is a garden, she tried to summon that bright, hopeful thought from the lavender field.

But now it seemed to her that this garden, her inner, infinitely precious garden, was being stalked by a stranger – invisible and merciless – with the cold, appraising gaze of a gardener, pausing by the most beautiful, most heart-treasured flowers, ready to rip them out by the roots. And the first petal had already fallen onto the dark earth.

Chapter 3

A Whisper from the White Room

The idea of a Sunday trip to the National Gallery, intended to distract and comfort, failed with a resounding, albeit quiet, crash. They made it to the majestic neoclassical building with its monumental columns, even bought tickets from an impassive cashier in a strict uniform, and managed to stand for about ten minutes in the semi-darkness of the hall before Titian’s «Venus with a Mirror.» Amelia stared at the thick, velvety shadows on the canvas, the complex, pearlescent color of the goddess’s skin, the saturated, deep ultramarine of the draperies in the background, trying to find solace in this time-tested harmony, in the genius backed by a steady hand and a clear gaze. But it was futile. Her own vision treacherously swam. And when they moved to the hall of Flemish painting, and her eyes fell on a portrait by van Dyck where a courtly dandy was clad in a cloak of scarlet paint, it suddenly flared with an alarming, unnatural, almost neon light, forcing her to look away sharply, as if from a camera flash. When they approached the Turner room, where the air in the paintings seemed permeated with golden light, mist, and endless movement, she grew so dizzy she had to grab Luca’s solid forearm to keep from losing her balance.