полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 534, February 18, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 534, February 18, 1832

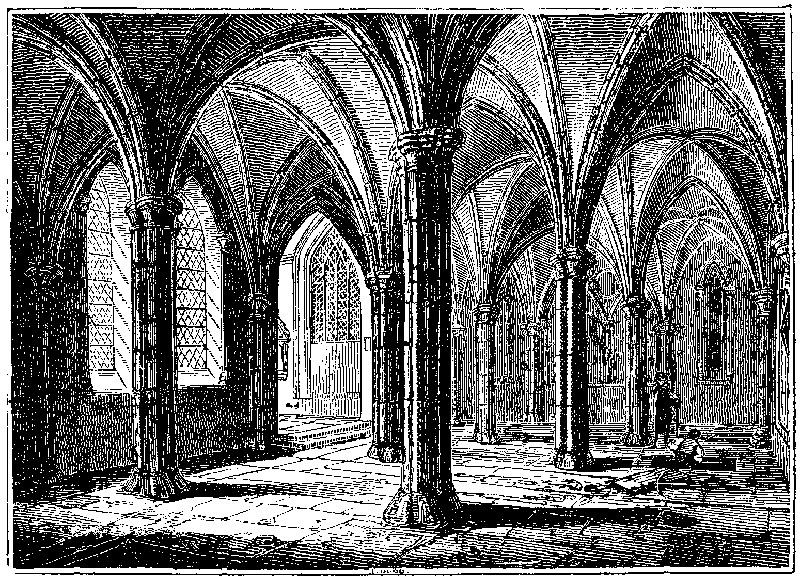

OUR LADY'S CHAPEL,

ST. SAVIOUR, SOUTHWARK

The Engraving represents the interior of the Virgin Mary's Chapel, commonly called the Lady Chapel, and appended to the ancient collegiate church of St. Saviour, Southwark. The exterior view of the Chapel will be found in No. 456 of The Mirror. About eighteen months since part of the western side of the High-street was removed for the approach to the New London Bridge, when this Chapel was opened to view; but its dilapidated appearance was rather calculated to interest antiquarian than public curiosity. The London Bridge Committee recommended the parishioners of St. Saviour to cause the Chapel to be pulled down, and their selfish suggestion would have been complied with, had not some enlightened and public-spirited individuals stepped forth to frustrate the levellers. The parishioners now became two parties. One contended for the restoration of the Chapel, as "one of the most chaste and elegant specimens of early pointed architecture of the thirteenth century of which this country can boast." The levellers, whose muckworm minds, and love of the arts is only shown in that of money-getting—maintained that the demolition of the Chapel would be "a pecuniary saving;" but theirs was a penny-wise and pound-foolish spirit; for, by removing the Chapel, a greater expense would be incurred than in its restoration. The folks could not understand plain figures, and so resolved to take the sense and nonsense of the parish, and the subject has been decided by a majority of 240 in favour of repairing the Chapel. The funds for this purpose, it should be understood, were in course of provision by public subscription, so that the blindness of party zeal threatened to reject a special advantage—the public would find the money if they would allow the Chapel to remain—whereas, had the demolition taken place, the parishioners must themselves have defrayed the consequent expenses. Historians loudly condemn the royal and noble thieves who plundered the Coliseum and the Pantheon to build palaces, yet there are men in our times, who would, if they could, take Dr. Johnson's hint to pound St. Paul's Church into atoms, and with it macadamize their roads; or fetch it away by piecemeal to build bridges with its stones, and saw up its marble monuments into chimneypieces.

The church of St. Saviour is built in the form of a cathedral, with a nave, side aisles, transepts, a choir, with its side aisles; and the chapel of St. John, which now forms the vestry, and the chapel of the Virgin Mary, or Our Lady. To the east end of the latter there has since been added a small chapel, called the Bishop's Chapel. Another chapel, (of St. Mary Magdalen,) was also connected with the south aisle of the church. The parishioners seem to have hitherto neglected the Lady Chapel, and to have shown their cupidity in ages long past. Through the influence of Dr. Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, they were allowed to purchase the church of that wholesale sin-salesman, Henry VIII.; but after the parish had obtained the grant of the church, they let the Lady Chapel to one Wyat, a baker, who converted it into a bake-house. He stopped up the two doors which communicated with the aisles of the church, and the two which opened into the chancel, and which, though visible, still remain masoned up. 1 In 1607, Mr. Henry Wilson, tenant of the Chapel of the Holy Virgin, found himself inconvenienced by a tomb "of a certain cade," and applied to the vestry for its removal, which was very "friendly" consented to, "making the place up again in any reasonable sort." 2 In this state it continued till the year 1624, when the vestry restored it to its original condition, at an expense of two hundred pounds. "More than that sum," observes the Rev. Mr. Nightingale, "I should conceive would now be required to repair this venerable part of St. Saviour's Church in such a manner as is absolutely necessary. The pillars have in a great degree lost their perpendicular position: the mouldings and mullions of the windows are distorted in the most shameful manner; the walls are rapidly hastening to their final decay; and the whole place appears to be destined to become once more the resort of hogs and vermin of every description. That this should be the case is a great disgrace to the parish, and an insult to the diocese, in which St. Saviour's Church holds so conspicuous a character." 3

The roof of the Chapel is divided into nine groined arches, supported by six octangular pillars in two rows, having small circular columns at the four points. At the back of the altar-screen of the church 4 are some tracery compartments, probably, according to Mr. Bray, once affording through them a view of this chapel. In the east end, on the north side, are three lancet-shaped windows, forming one great window, divided by slender pillars, and having mouldings, with zig-zag ornaments. The tracery windows on the south side are masoned up, but much of the original tracery remains. At the north-east corner are remains of sharp-pointed arches; here also is an enclosure with table, desk, and elevated seat. This part is, properly speaking, the Bishop's Court; but this name is common to the whole chapel, in which the Bishop of Winchester holds his Court; and in which are held the visitations for the Deanery of Southwark.

The annexed view was taken from the north-west entrance, and shows the character of the groined roof, the supporting pillars, and the entrance to the Bishop's Chapel adjoining, by an ascent of two steps; this Chapel being named from the Tomb of Bishop Andrews, formerly standing in the centre of it. We recommend the reader to a clever paper in the Gentleman's Megazine for the present month, in which the writer proves that Our Lady's Chapel, so far from being an excrescence, as has been idly stated, "bears the same relation to the church an the head does to the body."

NIGHT-MARE

(For the Mirror.)Sleeping in night-mare's thunderstorm-wove lap,On sunless mountain high above the pole;With ice for sheets, and lightning for a cap,And tons of loadstones weighing on his soul;And eye out-stretched upon some vasty mapOf uncouth worlds, which ever onward rollTo infinite—like Revelation's scroll.Now falling headlong from his mountain bedDown sulph'rous space, o'er dismal lakes;Now held by hand of air—on wings of leadHe tries to rise—gasping—the hands' hold breaks,And downward he reels through shadows of the dead,Who cannot die though stalking in hell's flakes,Falling, he catches his heart-string on some hook, and—wakes.E.H. 5LACONICS

There is nothing to be said in favour of fashion, and yet how many are contented implicitly to obey its commands: its rules are not even dictated by the standard of taste, for it is constantly running into extremes and condemns one day what it approves the next.

There are some people so incorrigibly stupid and prosing, that wherever they are anxious of securing respect, silence would be their best policy.

As we advance in age, it is singular what a revolution takes place in our feelings. When we arrive at maturity an unkind word is more cutting and distresses us more than any bodily suffering; in our youth it was the reverse.

There is nothing so ravishing to the proud and the great (with all their resources for enjoyment) as to be thought happy by their inferiors.

Such are the casualties of life, that the presentiment of fear is far wiser than that of hope; and it would seem at all times more prudent to be providing against accident, than laying out schemes of future happiness.

The character of any particular people may be looked for with best success in their national works of talent.

There is no absurdity in approving as well as condemning the same individual; for as few people are always in the right, so on the other hand it is improbable they should be always in the wrong.

The most elegant flattery is at second hand; viz., to repeat over again the praises bestowed by others.

Ignorance, simple, helpless ignorance, is not to be imputed as a fault; but very often men are wilfully ignorant.

We have fewer enemies than we imagine: many are too indolent to care at all about us, and if the stream of censure is running against us, the world is too careless to oppose it. If we could hear what is said of us in our absence we should torment ourselves without real cause, for we should seldom hear the real sentiments of the speaker; many things are said in mere wantonness, and many more from the desire of being brilliant.

The man who feels he is in the right is seldom dogmatical, for truth is always calm and requires not violence to enforce her arguments: we should desist from the contest the moment we feel anxious about victory, because that anxiety must make us less particular about the truth.

Quickness of intellect is no proof of solidity: the deepest rivers flow on the smoothest.

The reason why there are so few instances of heroism in modern times is the total decay of political virtue: we are broken up into small parties and associate only with our families, thus forgetting the public, in our regard for private interest: the ancients were taught rather to live for the benefit of the whole community.

An over-refined philosophy begets sensitiveness, and is as little to be coveted as a moderate share of it is beneficial.

It seems to be the business of life to lay by fresh cause for anxiety and discontent by increasing our estate; whereas we should rather know how to lose it all, and yet be contented.

There are some people, who though very amiable in the main, and obliging in their offices to others, have yet that most unhappy propensity of being gloomy over every thing.

It is one of the wisest provisions of Fortune that the same vices which ruin our estates, take away also the means of enjoying them by depriving us of health.

There is more virtue in obscurity than is commonly supposed; and perhaps there have been nobler specimens of magnanimity in low life, than even the page of history can boast.

Knowledge of the world must be combined with study, for this, as well as better reasons: the possession of learning is always invidious, and it requires considerable tact to inform without a display of superiority, and to ensure esteem, as well as call forth admiration.

Deceit has the effect of impoverishing, as well as enriching, men: the prodigal becomes poor by pretending to be richer than he really is, while seeming poverty is the very making of a miser.

F.

STANZAS TO THE SPIRIT OF MORNING

(For the Mirror.)Angel of morn! whose beauteous homeIn light's unfading fountain lies;Whose smiles dispel night's sable gloom,And fill with splendour earth and skies,While o'er the horizon pure and pale,Thy beams are dawning, thee I hail.The star that watches, pure and lone,In yon clear heaven so silently,Looks trembling from its azure throneUpon thy beaming glories nigh;And yields to thee first-born of day,Reluctantly its heavenly sway.Sweet spirit, with that early ray,Which steals so softly through the gloom,Trembling and brightening in its way,What beauties o'er creation come;Ere thy unclouded smiles ariseIn all their splendour through the skies.The rosy cloud—the azure sky,Earth—ocean, with its heaving breast,Where thy bright hues reflected lie,And there in varying beauty rest,Rejoice in thee; and from the grove,To hail thee, bursts the voice of love.Eternal beauty round thee dwells,And joy thine early steps attends,While music wildly breathing swells,And with thy gales of perfume blends:Pure, beautiful you smile above,Like youth's fond dreams of hope and love.Thy skies of blue, thy beaming light,Thy gales so balmy, wild, and free,Thy lustre on the mountain's height,Have charms beyond all else for me;Whilst my glad spirit fain would riseTo hail and meet thee in the skies.SYLVA.NOTES OF A READER

BRITAIN'S HISTORICAL DRAMA

We understand Mr. Pennie's design, in this volume, to be the chronological arrangement of certain incidents of each king's reign in a series of National Tragedies. There are four such tragedies in the present portion, commencing with Arixina in which figure Julius Caesar, Cassfelyn, and Cymbaline, and extending to Edwin and Elgiva: the titles of the intervening pieces are the Imperial Pirate and the Dragon King. There is much wild and beautiful romance in the diction, but we take the most attractive portion to be the lyrical portion, as the Chants, Dirges, and Choruses. We recommend them as models for the play-wrights who do such things for the acting drama, and if the poetship to a patent theatre be worth acceptance, we beg to commend Mr. Pennie to the notice of managers. The poet of the King's Theatre figures in the bills of the day, and yet he is but a translator.

It is difficult to select an entire scene for quotation, so that we take a specimen from Arixina:

CHORUS OF BARDS

DIRGESEMI CHORUSMightiest of the mighty thou!Regal pearl-wreaths decked thy brow;On thy shield the lion shone,Glowing like the setting sun!And thy leopard helmet's frown,In the day of thy renown,O'er thy foemen terror spread,Grimly flashing on thy head.Master of the fiery steed,And the chariot in its speed,—As its scythe-wedged wheels of bloodThrough the battle's crimson flood,Onward rushing, put to flightE'en the stoutest men of might,—Age to age shall tell thy fame;Thine shall be a deathless name!Bards shall raise the song for theeIn the halls of Chivalry.GRAND CHORUSHis shall he a noble pyre!Robes of gold shall feed the fire;Amber, gums, and richest pearlOn his bed of glory hurl:Trophies of his conquering might,Skulls of foes, and banners bright,Shields, and splendid armour, wonWhen the combat-day was done,On his blazing death-pile heap,Where the brave in glory sleep!And the Romans' vaunted pride,Their eagle-god, in blood streams dyed,Which, amid the battle's roar,From their king of ships he tore;Hurl it, hurl it in the flame,And o'er it raise the loud acclaim!Let the captive and the steedOn his death-pile nobly bleed;Let his hawks and war-dogs shareHis glory, as they claimed his care.SEMI-CHORUSSilent is his hall of shieldsIn Rath-col's dim and woody fields,Night-winds round his lone hearth singThe fall of Prythian's warlike king!—Now his home of happy restIs in the bright isles of the west;There, in stately halls of gold,He with the mighty chiefs of old,Quaffs the horn of hydromelTo the harp's melodious swell;And on hills of living green,With airy bow of lightning sheen,Hunts the shadowy deer-herd fleetIn their dim-embowered retreat.He is free to roam at willO'er sea and sky, o'er heath and hill,When our fathers' spirits rushOn the blast and crimson gushOf the cloud-fire, through the storms,Like the meteor's brilliant forms,He shall come to the heroes' shoutIn the battle's gory rout;He shall stand by the stone of death,When the captive yields his breath;And in halls of revelryHis dim spirit oft shall be.GRAND CHORUSShout, and fill the hirlass horn,Round the dirge-feast quaff till morn;Songs and joy sound o'er the heath,For he died the warrior's death!Garlands fling upon the fire,His shall be a noble pyre!And his tomb befit a king,Encircled with a regal ringWhich shall to latest time declare,That a princely chief lies there,Who died to set his country free,Who fell for British liberty;His renown the harp shall singTo mail clad chief and battle-king,And fire the mighty warrior's soulLong as eternal ages roll!The Notes to each Tragedy are very abundant. Indeed, they are of the most laborious research. We quote an extract relative to "grinning skulls" as terrifically interesting:

"The British warriors preserved the bones of their enemies whom they slew; and Strabo says of the Gauls (who were, as he informs us, far less uncivilized than the Britons, but still nearly resembled them in their manners and customs,) that when they return from the field of battle they bring with them the heads of their enemies fastened to the necks of their horses, and afterwards place them before the gates of their cities. Many of them, after being anointed with pitch or turpentine, they preserve in baskets or chests, and ostentatiously show them to strangers, as a proof of their valour; not suffering them to be redeemed, even though offered for them their weight in gold. This account is also confirmed by Diodorus. Strabo says that Posidonius declared he saw several of their heads near the gates of some of their towns,—a horrid barbarism, continued at Temple-bar almost down to the present period."

Lastly, Speaking and Moving Stones:

"Girald Cambrensis gives an account of a speaking-stone at St. David's in Pembrokeshire. 'The next I shall notice is a very singular kind of a monument, which I believe has never been taken notice of by any antiquarian. I think I may call it an oracular stone: it rests upon a bed of rock, where a road plainly appears to have been made, leading to the hole, which at the entrance is three feet wide, six feet deep, and about three feet six inches high. Within this aperture, on the right hand, is a hole two feet diameter, perforated quite through the rock sixteen feet, and running from north to south. In the abovementioned aperture a man might lie concealed, and predict future events to those that came to consult the oracle, and be heard distinctly on the north side of the rock, where the hole is not visible. This might make the credulous Britons think the predictions proceeded solely from the rock-deity. The voice on the outside was distinctly conveyed to the person in the aperture, as was several times tried.'—Arch. Soc. Ant. Lond. vol. viii.

"The moving stones, or Logans, were known to the Phoenicians as well us the Britons. Sanconiatho, in his Phoenician History, says, that Uranus devised the Boetylia, Gr.; Botal or Bothal, Irish; Bethel, Heb., or stones that moved as having life.—Damascius, an author in the reign of Justinian, says he had seen many of these Boetylia, of which wonderful things were reported, in Mount Libanus, and about Heliopolis, in Syria."

The volume, a handsome octavo of more than 500 pages, has been, we perceive, published by subscription: the list contains about 400 names, with the King at the head. This is sterling patronage, yet not greater, if so great, as Mr. Pennie deserves. The Preface, we think, somewhat unnecessarily long: it needed but few words to commend the drama of our early history to the lovers of literature, among whom we do not reckon him who is insensible to the charms of such plays as Cymbeline, Julius Caesar, the Winter's Tale, or Macbeth. Mr. Pennie mentions the popularity of Pizarro, "which faintly attempts to delineate the customs of the Peruvians" as a reason for "the hope that is in him" respecting the fate of his own tragedies. To our minds, Pizarro is one of the most essentially dramatic or stage-plays of all our stock pieces. It is of German origin, though Sheridan is said to have written it over sandwiches and claret in Drury Lane Theatre. The country, the scenery, and costume have much to do with this stage effect, and even aid the strong excitement of conflicting passions which pervades every act. Its representation is a scene-shifting, fidgeting business, but its charms tempt us almost invariably to sit it out.

Returning to Mr. Pennie's Tragedies, we must add that a more delightful collection of notes was never appended to any poem. Would that all commentators had so assiduously illustrated their text. Here is none of the literary indolence by which nine out of ten works are disfigured, nor the fiddle-faddle notes which some folks must have written in their dreams.

SNATCHES FROM EUGENE ARAM

A Landlord's Benevolence.—No sooner did he behold the money, than a sudden placidity stole over his ruffled spirit:—nay, a certain benevolent commiseration for the fatigue and wants of the traveller replaced at once, and as by a spell, the angry feelings that had previously roused him.

A "Rich" Man.—One who "does not live so as not to have money to lay by."

An old Soldier.—Set me a talking, and let out nothing himself;—old soldier every inch of him.

A Scholar.—A man not much inclined to reproduce the learning he had acquired:—what he wrote was in very small proportion to what he read.

Study of Mankind.—There seems something intuitive in the science which teaches us the knowledge of our race. Some men emerge from their seclusion, and find, all at once, a power to dart into the minds and drag forth the motives of those they see; it is a sort of second sight, born with them, not acquired.

Happiness.—No man can judge of the happiness of another. As the moon plays upon the waves, and seems to our eyes to favour with a peculiar beam one long track amidst the waters, leaving the rest in comparative obscurity; yet all the while she is no niggard in her lustre—for the rays that meet not our eyes seem to us as though they were not, yet she, with an equal and unfavouring loveliness, mirrors herself on every wave: even so, perhaps, Happiness falls with the same brightness and power over the whole expanse of life, though to our limited eyes she seems only to rest on those billows from which the ray is reflected back upon our sight.

Influence of Cities.—When men have once plunged into the great sea of human toil and passion, they soon wash away all love and zest for innocent enjoyments. What was once a soft retirement, will become the most intolerable monotony; the gaming of social existence—the feverish and desperate chances of honour and wealth, upon which the men of cities set their hearts, render all pursuits less exciting, utterly dull and insipid.

Love.—There is a mysterious influence in nature, which renders us, in her loveliest scenes, the most susceptible to love. * * In all times, how dangerous the connexion, when of different sexes, between the scholar and the teacher! Under how many pretences, in that connexion, the heart finds the opportunity to speak out.

Passion—The doubt and the fear—the caprice and the change, which agitate the surface, swell also the tides of passion.

Poverty—makes some humble but more malignant.

Want.—How many noble natures—how many glorious hopes—how much of the seraph's intellect, have been crushed info the mire, or blasted into guilt, by the mere force of physical want?

Benevolence.—How poor, even in this beautiful world, with the warm sun and fresh air about us, that alone are sufficient to make us glad, would be life, if we could not make the happiness of others.

Eloquence.—The magic of the tongue is the most dangerous of all spells.

Genius.—There is a certain charm about great superiority of intellect, that winds into deep affections which a much more constant and even amiability of manners in lesser men, often fails to reach. Genius makes many enemies, but it makes sure friends—friends who forgive much, who endure long, who exact little; they partake of the character of disciples as well as friends.

Experience.—'Tis a pity that the more one sees, the more suspicious one grows. One does not have gumption till one has been properly cheated—one must be made a fool very often in order not to be fooled at last!

Cat-kindness.—Paw to-day, and claw to-morrow.

London at Night.—One of the greatest pleasures in the world is to walk alone, and at night, (while they are yet crowded) through the long lamp-lit streets of this huge metropolis. There, even more than in the silence of woods and fields, seems to me the source of endless, various meditation.

How easy it is to forget!—The summer passes over the furrow, and the corn springs up; the sod forgets the flower of the past year; and the battlefield forgets the blood that has been spilt upon its turf; the sky forgets the storm; and the water the noon-day sun that slept upon its bosom. All Nature preaches forgetfulness. Its very order is the progress of oblivion.