полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 554, June 30, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 554, June 30, 1832

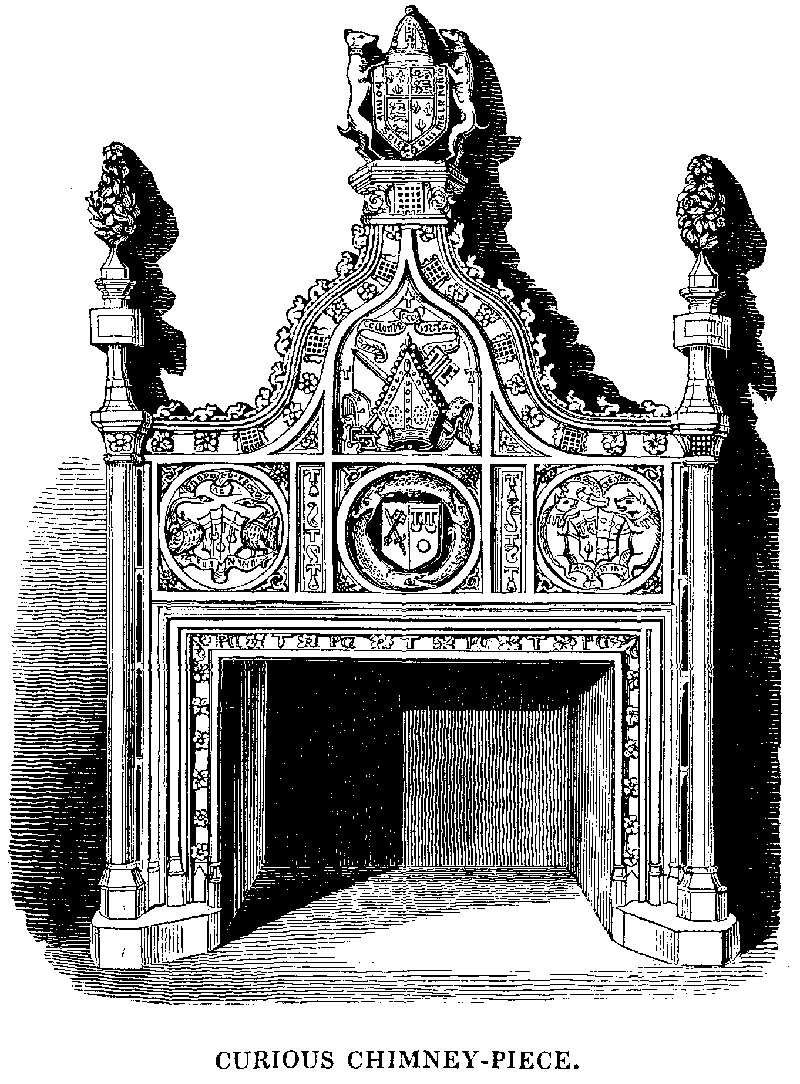

We select this Engraving as an illustration of the elaborate sculptural decoration employed in domestic architecture about three centuries since; but more particularly as a specimen of the embellishment of the ecclesiastical residences of that period. It represents a chimney-piece erected in the Bishop's palace at Exeter, by Peter Courtenay, who was consecrated Bishop of Exeter, A.D. 1477, and translated to Winchester, A.D. 1486. He had formerly been master of St. Antony's Hospital, in London.

The bishop was third son of Sir Philip Courtenay of Powderham, knight, (fifth son of Hugh Courtenay, second Earl of Devonshire), who died 1463.

He was educated at Exeter College, Oxford; made archdeacon of Exeter 1453; dean of the same church, 1477.

He died 1491, and was probably buried in the chancel at Powderham, where is an effigy of a bishop inlaid in brass. He built the north tower of Exeter cathedral, and placed in it a great bell, called after him Peter's bell, with a clock and dial: he built also the tower and good part of the church at Honiton (which before was only a chapel, now the chancel). In the windows of the tower are the arms of his parents, now lost; but his paternal arms are on the pillars of the chancel. 1

The heraldic embellishments of the chimney-piece are as follow:—

"The arms of Courtenay impaled by those of the see of Exeter are in the centre compartment. In that on the left hand is the former coat single, supported by two swans collared and chained. Motto Arma Petri Exon epi. And on the right hand it impales Hungerford, supported by two boars with the Courtenay label round their necks. Motto Arma Patris et Matris.

"Above the centre compartment is the mitre, with the arms of the see, and a label inscribed Colompne ecclesie veritatis p'conie; 2 and here the T is thrice repeated.

"The moulding of the arch is charged with the portcullis and foliage alternately; and on the point are the royal arms in a garter, and supported by two greyhounds.

"The T with the bell appendant occurs on the sides of the centre coat; also the T single and labels, and over the top of the chimney the T and P C for Peter Courtenay.

"The three Sickles and the Sheaf in the angles of the three compartments are the badges of the barons of Hungerford."

Further explanation is necessary, as well as interesting for its connexion with two popular origins—St. Antony's fire, and St. Antony, or "Tantony's Pig."

"The monks of the order of St. Antony wore a black habit with the letter T of a blue colour on the breast. This may sufficiently account for the appearance of that figure among the ornaments of Bishop Courtenay's arms. The following extract from Stow's Survey of London may serve to explain the appendant Bell.

"The Proctors of this hospital were to collect the benevolence of charitable persons towards the building and supporting thereof. And among other things observed in my youth I remember that the officers charged with the oversight of the markets in this city did divers times take from the market people pigs starved, or otherwise unwholesome for men's sustenance: these they did slit in the ear. One of the Proctors of St. Antony tied a bell about the neck, and let it feed among the dunghills, and no man would hurt it, or take it up; but if any gave them bread, or other feeding, such they would know, watch for, and daily follow, whining till they had something given them; whereupon was raised a proverb, 'such a one will follow such a one and whine as it were an Antony pig;' but if such a pig grew to be fat, and came to good liking, as oft times they did, then the Proctor would take him up to the use of the hospital."

"These monks, with their importunate begging were so troublesome, that if men gave them nothing, they would presently threaten them with St. Antony's fire, so that many simple people, out of fear or blind zeal, every year used to bestow on them a fat pig or porker (which they ordinarily painted on their pictures of the saint), whereby they might procure their good will, prayers, and be secure from their menaces.

"The knights of this order (of St. Antony) wore a collar of gold, with an hermit's girdle, to which hung a crutch and a little bell. 3 See in the Gentleman's Magazine for the year 1750, the plate of the orders of knighthood, where T, whether a letter or crutch, is given to the order of St. Antony of Ethiopia.

"The saint is always represented with this appendage in Missals, and on monuments, the T hanging from his girdle, and the bell from the neck of the pig at his feet."

We are indebted for this subject to the Vetusta Monumenta of the Antiquarian Society.

The form of the arch will be recognised as strictly of the ecclesiastical architectural character; and, with reference to this style, we may observe that "the ecclesiastical residence, the dwelling of the mitred abbot with his train of shaven devotees, or of the princely bishop and humbler priest, naturally was designed to correspond with the consecrated edifice round which these buildings were usually grouped; and hence the architecture of the abbey or priory is essentially of a piece with that of the cathedral." Reverting to the chimney-piece, it should be added that formerly both on the continent, as well as in England, fire-places and chimneys were decorated with architectural ornaments, as columns, entablatures, statues, &c., like the entrance to a small temple; now they are mostly made of marble, and more for the office of sculptural decoration than for the orders of architecture.

SONG WRITTEN IN IMITATION OF COWLEY'S MISTRESS

(For the Mirror.)Oh, where didst borrow that last sigh,And that relenting groan;Ladies that sigh and not for love,Usurp what's not their own.Love's arrows sooner armour pierceThan that soft snowy skin;Thine eyes can only teach us love,They cannot take it in.J.H.L.H. 4

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

THE GROANING TREE OF BADDESLEY, HAMPSHIRE

(For the Mirror.)Gilpin, in his "Remarks on Forest Scenery," says, A cottager, who lived near the centre of the village, heard frequently a strange noise behind his house, like that of a person in extreme agony. Soon after, it caught the attention of his wife who was then confined to her bed. She was a timorous woman, and being greatly alarmed, her husband endeavoured to persuade her that the noise she heard was only the bellowing of the stags in the forest. By degrees, however, the neighbours on all sides heard it, and the circumstance began to be much talked of. It was by this time plainly discovered that the groaning noise proceeded from an Elm, which grew at the bottom of the garden. It was a young, vigorous tree, and, to all appearance, perfectly sound. In a few weeks the fame of the groaning tree was spread far and wide; and people from all parts flocked to hear it. Among others it attracted the curiosity of the late Prince and Princess of Wales, who resided at that time, for the advantage of a sea-bath, at Pilewell, within a quarter of a mile of the groaning tree.

Though the country people assigned many superstitious causes for this strange phenomenon, the naturalist could assign no physical one, that was in any degree satisfactory. Some thought it was owing to the twisting and friction of the roots: others thought that it proceeded from water, which had collected in the body of the tree; or, perhaps, from pent air: but the cause that was alleged appeared unequal to the effect. In the mean time, the tree did not always groan; sometimes disappointing its visitants; yet no cause could be assigned for its temporary cessations, either from seasons, or weather. If any difference was observed, it was thought to groan least when the weather was wet, and most when it was clear and frosty; but the sound at all times seemed to come from the roots.

Thus the groaning tree continued an object of astonishment, during the space of eighteen or twenty months, to all the country around; and for the information of distant parts, a pamphlet was drawn up, containing a particular account of it. A gentleman of the name of Forbes, making too rash an experiment to discover the cause, bored a hole in its trunk. After this it never groaned. It was then rooted up, with a further view to make a discovery; but still nothing appeared which led to any investigation of the cause. It was universally, however, believed, that there was no trick in the affair; but that some natural cause really existed, though never understood.—(Vol. I. p. 163.)

P.T.W.

CURIOUS PARTICULARS RELATING TO HURLEY, IN BERKSHIRE

(For the Mirror.)Mr. Ireland, in his "Picturesque views on the river Thames," observes that "the fascinating scenery of this neighbourhood has peculiarly attracted the notice of the clergy of former periods."

Hurley Place was originally a monastery. In the Domesday Book, it is said to have lately belonged to Edgar; but was then the property of Geoffrey de Mandeville, who received it from William the Conqueror, as a reward for his gallant conduct in the battle of Hastings; and in the year 1086 founded a monastery here for Benedictines, and annexed it as a cell to Westminster Abbey, where the original charter is still preserved.

On the dissolution of the monasteries, Hurley became the property of a family named Chamberlain, of whom it was purchased, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, by Richard Lovelace, a soldier of fortune, who went on an expedition against the Spaniards with Sir Francis Drake, and erected the present mansion on the ruins of the ancient building, with the property he acquired in that enterprise. The remains of the monastery may be traced in the numerous apartments which occupy the west end of the house; and in a vault beneath the hall some bodies in monkish habits have been found buried. Part of the chapel, or refectory, also, may be seen in the stables, the windows of which are of chalk; and though made in the Conqueror's time, appear as fresh as if they were of modern workmanship. The Hall is extremely spacious, occupying nearly half the extent of the house. The grand saloon is decorated in a singular style, the panels being painted with upright landscapes, the leafings of which are executed with a kind of silver lacker. The views seem to be Italian, and are reputed to have been the work of Salvator Rosa, purposely executed to embellish this apartment. The receipt of the painter is said to be in the possession of Mr. Wilcox, the late resident.

During the reigns of Charles II., and James, his successor, the principal nobility held frequent meetings in a subterraneous vault beneath this house, for the purpose of ascertaining the measures necessary to be pursued for reestablishing the liberties of the kingdom, which the insidious hypocrisy of one monarch, and the more avowed despotism of the other, had completely undermined and destroyed. It is reported also, that the principal papers which produced the revolution of 1688, were signed in the dark recess at the end of the vault. These circumstances have been recorded by Mr. Wilcox, in an inscription written at the extremity of the vault, which, on account of the above circumstances, was visited by the Prince of Orange after he had obtained the crown; by General Paoli in the year 1780; and by George III. on the 14th of November, 1785.

The Lovelace family was ennobled by Charles I., who in the third year of his reign, created Richard Lovelace, Baron Hurley, which title became extinct in 1736. The most valuable part of the estate was about that time sold to the Greave family and afterwards to the Duke of Marlborough: the other part, consisting of the mansion house and woodlands, to Mrs. Williams, sister to Dr. Wilcox, who was bishop of Rochester about the middle of the last century. This lady was enabled to make the purchase by a very remarkable instance of good fortune. She had bought two tickets in one lottery, both of which became prizes: the one of 500l., the other of 20,000l. From the daughter of Mrs. Williams it descended to Mr. Wilcox in the year 1771.—Beauties of England and Wales.

P.T.W.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

CLAVERING'S AUTO-BIOGRAPHY

Containing opinions, characters, &c. of his CotemporariesShelley had some excellent qualities: I attribute his eccentricities to a spice of insanity. He often wrote unintelligibly;—sometimes in short lyrics, beautifully. The ashes of him and Keats sleep together in the Protestant chapel at Rome. I am resolved once more to visit Lirici, where the funeral pile of his relics were lighted. I am never so happy as when I am travelling on the Continent; the mere change of air, and locomotion, gives me vigour. I saw old Sir William Wraxall at Dover, a few days before he died, and meant to have accompanied him to Paris. He was still full of anecdote, to which it was necessary to listen with caution; but his information was often curious and valuable. He was one of our oldest litterateurs.

Some years ago I met Sismondi: I could not agree with his ULTRA-LIBERAL politics! He has married an English lady, but does not seem to love the English. He himself once suffered from excessive revolutionism, and was condemned to death by it when young, about 1794, in the reign of terror, when Monsieur Raville and others were shot at Geneva. One would have thought that this would have made a convert of him in favour of legitimate governments. But I forget: he does not call them legitimate! He is a thick man, of middle height, with strong features, sallow, with weak eyes, rapid and rather indistinct in his articulation, with a character of great generosity and kindness; but not very tolerant to others in political thinking.

About 1802, strange lawyers perched upon the judgment-seat. Law, Pepper, Arden, and John Mitford! The little Pepper once took it into his head to review a cavalry regiment of fencibles, when he was Master of the Rolls. An unruly horse of one of the officers got head in a charge, and nearly ran over the affrighted judge. I was on the field, saw it all; and heard the small, staring man's terrible shriek! He swore that nothing should ever make him go soldiering again! He could not recollect his law-cases for a fortnight to come! He had some fun about him, and was always crying out, "Ne sutor ultra crepidam, ne sutor ultra crepidam." and indeed he looked like a shoemaker. A bowel-complaint carried him off. Perhaps it was the fright!

A certain learned theological bishop of that fraternity, a warm controversialist, long since dead, was of an amorous disposition. One day, being left alone with a pretty young lady, he began to be rude to her; she knocked off his prelated wig, and stamped it under her foot. At that time the footman entered, and all was confusion! The girl was in tears; the bishop's pate was bald. The footman was left to wonder! Some squibs appeared in the papers of the day, which few understood. I wrote a piquant epigram, which I will not revive. Old Thurlow, who was the prelate's friend and patron, laughed outright, and clapped me on the back when I dined with him a few days afterwards.

I have been more than once in company with Washington Irving, a most amiable man and great genius, but not lively in conversation. The engraved portraits I have seen of him are not very like him. He frequented the reading-room of Galignani at Paris, and seemed to have some literary connexions with him. There I saw Captain Medwin, the author of the book called Lord Byron's Conversations, which I believe to have been accurately reported. He was with his friend Grattan, the author of High-ways and Bye-ways. I was not personally acquainted with either of them. Grattan's flat nose is somewhat concealed in the print given of him in Colburn's Magazine, where this author, of course, makes a distinguished figure.

The late Professor Pictet, of Geneva, who had spent some of his early days in England, and was very fond of it, told me some curious anecdotes of his countryman De Lolme, whose book on the English constitution is much more commended than it deserves. He once endeavoured to set up a rival Journal to Old Swinton's Courrier de l'Europe, but his absurd denial of Rodney's victory ruined the project. De Vergennes, the French minister, patronized it. Brissot was connected with Swinton in the above-named Journal. One of Swinton's sons holds a high situation in the British Government in India:—another commanded a ship in the Company's service. Old Swinton was a Scotch jacobite, and forfeited.

Horace Walpole, who died Earl of Orford, was a little old man with small features—very lively and amusing,—who talked just as he wrote: but a little too fond of baubles and curiosities. He had a witty mind, but not a great one:—yet he was a man of genius. His family was ancient, but his vanity made him always endeavour to represent it of much more consequence than it was. They had a great deal of the Norfolk squierarchy about them. He could not bear his uncle Horace, the diplomatist, whose son, the grandfather of the present earl, with his little tie-wig, looked like an old-fashioned glover.

I have mentioned Mrs. Macauley, the historian. She had a dog latterly, of which she made a great pet, and on being asked why she bestowed so much care on it, she answered—"Why! are you aware whence it came? It is a true republican, and has been stroked by the hand of Washington!" The event of the French Revolution maddened her with joy; but when the news came of Louis the Sixteenth's escape, and before she heard he had been brought back, she took to her bed, wrote to her friends that she should die of the disappointment—and did die. She complained that Dr. Graham had given her a love-potion! Her young husband used her ill.

Tom Warton, the poet, was a good-natured man, but addicted to low company. He was fond of

"Smoking his pipe upon an alehouse bench;"He was tutor to Colonel North, the son of the minister, who thought he neglected him. This connexion, perhaps, led him to write the Life of Sir Thomas Pope, or rather that this family were founders of Warton's college. He also wrote the life of the President Bathurst, who was elder brother of Sir Benjamin Bathurst, a commercial man, father to the first Lord Bathurst, the friend of Pope the poet, and who lived to the age of ninety, in possession of his faculties,—always calling his son, the Chancellor, "the old man!" He was one of Queen Anne's twelve peers—but so rapid has been the extinction and change, that the Bathursts are now considered old nobility. He sprung from one of the Grey Coat families in the weald of Kent, the clothiers.

Old Dr. Farmer, the head of Emanuel College, Cambridge, Prebendary of Canterbury, and afterwards of St. Paul's, or Westminster, used to frequent a club in London, to which I belonged. He was at first reserved and silent: but his forte was humour and drollery. At Cambridge he neglected forms and ceremonies in his college too much: and was in all his glory when in dishabille in his study, with his cat by his side, and his Shakspeare tracts about him. He found no literature at Canterbury, and was disgusted with his brother members of the cathedral: quaint Dean Horne, and chattering romancing Dr. Berkeley, and his rhodomontading wife, were not suited to him, and as little her son Monke Berkeley, of whom she gave such an absurd and mendacious memoir, and who had none of his celebrated grandfather Bishop Berkeley's genius. Farmer had some cleverness, but no leading talent. He collected an immense quantity of rare and forgotten old English books—especially poetry and the drama—at a trifling price. Todd, the learned editor of Milton, Spencer, &c., was then a member of that cathedral; but as his literary superiority was not pleasant to those above him in that establishment, he was got rid of by promotion, elsewhere, out of their patronage. He wrote the lives of the Deans of that Church, which does not rise to more than local interest. It is a dull book.

It has been my fate to be Acquainted with Irish Secretaries. I saw much of little Charles Abbot—afterwards Speaker—and at last Lord Colchester. He was a pompous dwarf; yet of an analytical head. Nothing could be more amusing than to see him strut up the House of Commons to take the chair; nor was the amusement less to listen to him, when he delivered his edicts, or the thanks of the House from the chair. His sonorous voice issuing from a diminutive person, and the epigrammatic points of empty sentences, formed with great artifice, were in very bad taste—though much admired by a House which consisted of so few men of a classical education. His rise was extraordinary, because his talents little exceeded mediocrity. But he was a courtier, and an intriguant. He was the son of a schoolmaster at Colchester.

Swift, though of English extraction, was born in Ireland. From some memoranda of my grandfather's, I learn, that he did not speak of his residence with Sir William Temple at Moore Park, in Surrey, without spleen. He seemed to retain a sort of unwilling awe of Sir William; but not to have loved him. Sir William was a ceremonious courtier: Swift's early habits were somewhat rude and slovenly. Swift had genius, as Gulliver's travels prove; but there is no genius in his poetry. He was both proud and vain. His ancestor was the rector of a small living in Kent; his father an attorney. When I was quartered at Canterbury, I saw the monument for one of his ancestors, preserved out of the old church at St. Andrew's and replaced in the new one. The arms sculptured on it are totally different from what Swift erroneously supposes the family to have borne: this ancestor was minister of that parish—not a prebendary, as Swift represents. Miss Vanhomrigg was cousin of my grandfather, who considered that Swift had used her very cruelly.

I often met the late Monsieur Etienne Dumont, of Geneva, the friend and commentator of old Jeremy Bentham, at Romilly's house in London, in 1789. He was a man of astonishing talents, sagacity, acuteness, and clearness of head. What part he had in the brilliant effusions of Mirabeau, and in the French Revolution, may be seen by his posthumous work, just published at Paris, entitled Souvenirs de Mirabeau. He was a short, thick man, of coarse features, blear eyed, and slovenly in his dress; but of mild manners, hospitable, an excellent story-teller, and much beloved. I think he had been at one time librarian to old Lord Lansdowne. He died at Milan, in 1829, aged about 70. The French cannot contain their rage at the exposure that he was the spirit who moved their brilliant Mirabeau.

I was once talking to Anna Maria Porter about him, when she expressed her astonishment at the admiration I bestowed on him! She said, "I thought you was a Whig, and an aristocrat! how can you commend a revolutionary radical?" I answered, "You mistake his character, he is not a radical in the sense you mean! he considers Tom Paine's Rights of Man to be mischievous nonsense!" I could not convince her: but I made my peace with her by praising, with the utmost sincerity, her beautiful novel, The Recluse of Norway. I found her full of good sense, and with much command of language. She will forgive me for saying she had not the personal beauty of her gentle sister Jane. She paid many compliments to the imaginative vivants of the green island; for she perceived by my tones that I was an Irishman, though I am not sure, that she knew even my name; for the company was numerous, and of all countries. It was an evening assembly, in which the rooms were so full, that one could hardly move. Tommy Moore was there, and though he is a very little man, he was the great lion of the evening: all the young ladies were dying to see the bard whose verses they had chanted so often with thrilling bosoms, and tears running down their cheeks. They were not quite satisfied when they saw a diminutive man, not reaching five feet, with a curly natural brown scratch, handing about an ugly old dowager or two, who fondly leaned upon his arms, even though they discovered them to be ladies of high titles.