полная версия

полная версияПолная версия

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 557, July 14, 1832

It was an autumnal evening;—the sky looked wild and stormy, though the air was densely still, and save when a momentary breeze swept by, as the night was setting in, a general hush prevailed. A general character of intense loneliness pervaded the district they were traversing. Now and then a mountain stream would flash along the bosom of a valley and relieve the mind of the traveller; but rocks and mountains, heaths and dreary wilds succeeded with unwearying sameness. Time was creeping on. After passing over this wild, irregular district they at last entered into a dark valley, which seemed of some extent. The Lieutenant thought that he had been certainly led a very different route to his friend's house, from that which his guide was now leading him, and as the gloom was increasing, he seriously expostulated with the man on the subject. He replied that five miles were saved by cutting across the moors, on which they would enter after clearing the valley. A shade of suspicion now crossed over the Lieutenant's mind. There was something remarkable in the man's silence, and he resolved when they entered on the moors to put spurs to his horse and leave the rest to fate. The road which had been on the ascent for some time, now became exceedingly bad, and indeed almost impassable. Large masses of rock were scattered over the path, and deep hollow chasms, the effect of the violent storms which descend in these wilds, were continually endangering both horse and man. At length they began to descend. The moors lay at the foot of the hill. On this side, however, the road became worse and worse, and the night darker, so that although Dart had hitherto avoided danger with the remarkable sagacity which horses possess in such cases, his rider was obliged to descend, and lead the way himself. The Lieutenant had not gone far before he was suddenly felled to the ground by a blow aimed from behind. The violence of the shock fell principally on his shoulders, though there was no doubt his assailant had intended it for his head. He was a powerful and active young man, and a desperate struggle commenced between them. They continued for several minutes in this death-wrestle, during which time they had imperceptibly drawn close to the edge of tremendous precipice which bounded the road. Smyth already heard just below them the wild screaming of some ravens, who had been disturbed by the encounter; when he made a desperate effort on the very brink of the precipice—tore from his assailant's murderous grasp—and in another instant there was a void before him; a wild shriek of despair arose in the night blast, as the wretch bounded from crag to crag—and then there was a death-like stillness.

Smyth paused not to reflect. Dart was no where visible. He, therefore, descended as fast as possible, and after one or two falls occasioned by his impatience and the darkness of the night, at last entered on what appeared to be a vast moor. In a short time the moon rose. Two immense parallel masses of dense clouds stretched across the entire horizon; the upper limb of the planet, of a deep crimson, was alone visible betwixt them, and shed a sombre light over the waste. He thought he had seldom seen any thing so impressive; combined with the low moaning of the night-breeze, which rose and sank at intervals, with a wild and wailing murmur. The light was so indistinct that he could discover nothing of his horse, and in the lawless state of the country no time was to be lost in getting to a place of safety. But, the direction?

After wandering on for several miles, he at last struck on a path, and following it a short way, his attention was attracted to a glow of light, which rose just before him, on what appeared to be the surface of the moor. He cautiously advanced several steps, and perceived that the light rose near the edge of a declivity, and the noise of human voices was now distinctly apparent. Little doubt could exist that it was a haunt either of smugglers or insurgents, with the description of some of which the situation accurately corresponded. It would have been more prudent to have instantly retreated; but the organ of inquisitiveness was, we presume, very fully developed in Smyth; he stepped forward a little to have a better survey of the locale, when the ground or rather turf roof of a sort of outhouse, suddenly gave way under him, and he gently descended among some hay, with which the place was nearly filled. It may be supposed his curiosity received a sudden check by this adventure. An imperfectly constructed partition divided him from the party whose voices he had heard aloft. You might have heard his heart beat for two or three minutes, as it was very probable that the noise of his fall would have disturbed the inmates—but the conversation went on in the same monotonous tone.

"Och, Brine Morrice, avic, sure an that thief o' the worl', Will Guire, hasn't been after letten' the soger-officer com' over him?"

"Bad luck to him, Misthress Burke, agra, in troth I was jist awond'ring what keeps Tom Daly and the b'ys out—and them were to have had the red-coat these three hours agone!"

"Hisht jewel, I heard a noise—och, musha, its the b'ys sure enough—and the – Saxon with 'em, I'll be bail!"

At this moment several men arrived in front of the edifice, and, to the horror of Smyth proceeded first to the outhouse: the door was banged open, and after muttering something, a heavy substance was thrown in and the door again pulled to. Presently they entered the kitchen, and Smyth's heart beat high when his own name was mentioned. In the confusion of voices, he could not make out much of their brogue, but it appeared that the messenger sent by Colonel – had been waylaid, and the fellow that attempted his life was sent in his stead: this party had arranged to meet him at a certain place, on his return, but after waiting three hours, apprehending treachery, they came away. He could make out little else, except a volley of outlandish oaths at their unsuccessful trip. It appeared evident from this that the temptation of plunder had induced the guide to make the attack beforehand.

Every moment, however, that Smyth lingered in this den lessened his chance of escape. Immediately above him hung a piece of rope, and after a violent effort, he succeeded in getting his head once more into the fresh air; but just as he clambered out upon the turf, the noise aroused the dogs in the kitchen, and their furious barking, accompanied by a great stir amongst the men, gave wings to Smyth's feet, and he plunged forward at random again into the waste. At that moment the moon fell full upon his path, though dense masses of clouds were sailing across the sky. He soon found they had struck on his track, and already the yelling of dogs and men boomed distinctly on his ears. By that instinct with which men are often gifted in such cases, the footsteps of his pursuers already trod, as it were, upon his heart. The voices of the bloodhounds which were considerably in advance of the men, had an awful effect in the stillness of the night. His strength now began to give way—his heart beat thicker—he almost grew desperate, and more than once resolved to make a stand, and sell his life dearly. From the rapidity of the chase, a considerable distance had been traversed, and the sky which had long been threatening, now began to exhibit warnings of a storm. The moon was obscured by a vast gathering of clouds, and the deep stillness which had prevailed in the earlier part of the evening was succeeded by violent gusts of wind and large pattering drops. It was a dreary moment. The dogs were fast drawing on their victim, and nothing but despair and death stared him in the face. The ground now began to get irregular and varied, and a hope arose in his heart that he was getting on the verge of the moors. Still he was entirely ignorant as to the direction. The clouds then burst with a violence which their threatening aspect had long foretold, and in an instant Smyth was drenched to the skin; the ground became slippery, and the footing was precarious. Still he burst wildly onwards; he fancied he heard the noise of running water—he redoubled his now slackening speed, and in another instant came to the banks of what appeared a small river. He dashed into the rapid stream, and instead of crossing ran up the opposite side in the shallow part, knowing that the dogs would thus be thrown off the scent. He had not advanced far before they arrived at the brink he had left, and by their increased yelling, showed that they were at fault. He sustained many a severe and dangerous fall amongst the slippery stones in the river; but hope had sprung up in his heart, and it was not without a fervent prayer that he heard the shouts and yells of his pursuers wax fainter and fainter. In about half an hour he reached a small lake or tarn, as it is called in the north, which appeared to be the source of the stream. Here he had breathing time; but he was chilled with wet, and altogether in a dismal condition. He more than once thought he heard the voices of men and dogs in the blast; but their search was in vain, for about daybreak he reached a place of safety more dead than alive.

Here the loud snoring of Lieutenant –, put an end to the narration.

VYVYAN.

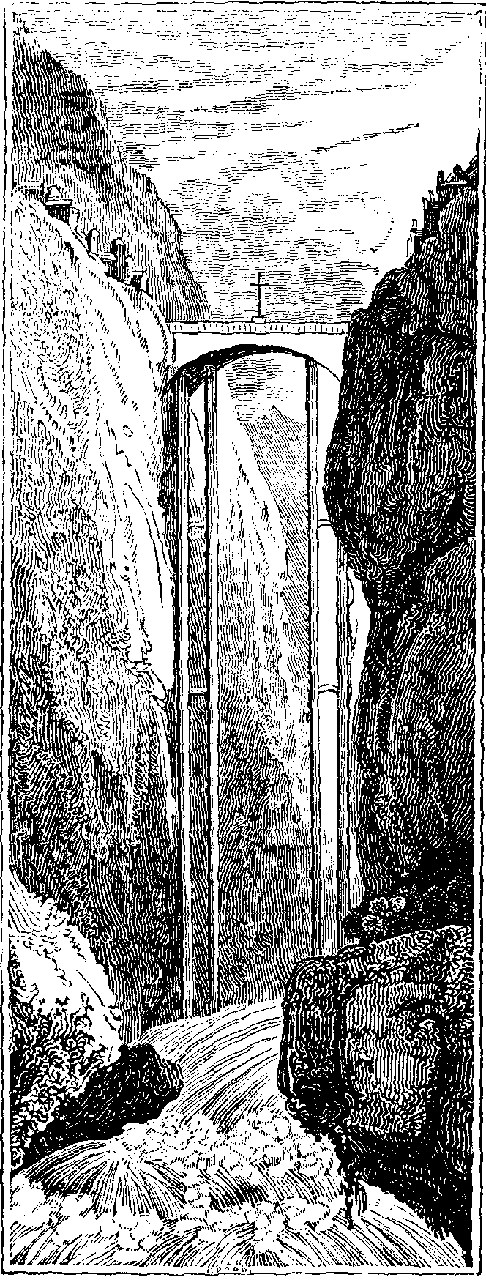

STUPENDOUS BRIDGE IN SPAIN

Bridges are amongst the noblest, if not the most ancient, triumphs of human art. Many of the specimens of former ages are admired for their massive solidity, as well as for the beauty of their architectural decoration. The present bridge, a fabric of the last century, has neither of these attractions, though it is constructed upon the best principle of modern bridge-building—that of having one single arch. Péronnet and De Chezi, two celebrated engineers, who are regarded as the founders of a new school of bridge architecture in France, made it their study to render the piers as light, and the arches as extended and lofty as possible; and the above bridge is a handsome structure of this class. It has been objected that the modern French bridges have not that character of strength and solidity which the ancient bridges possessed, and that in the latter, the eye is generally less astonished, but the mind more satisfied, than in the former. To these objections the Spanish bridge is by no means liable, as we shall proceed to show from its details.

The present bridge extends across the river, Guadiaro, in the South of Spain, and connects the romantic city of Ronda with its suburbs. The situation of the city, encircled by Guadiaro, is described by Mr. Jacob, 5 as follows:—

"It is placed on a rock, with cliffs, either perpendicular and abrupt towards the river, or with broken craggs, whose jutting prominences, having a little soil, have been planted with orange and fig trees. A fissure in this rock, of great depth, surrounds the city on three sides, and at the bottom of the fissure the river rushes along with impetuous rapidity. Two bridges are constructed over the fissure; the first is a single arch, resting on the rocks on the two sides, the height of which from the water is one hundred and twenty feet. The river descends from this to the second bridge, whilst the rocks on each side as rapidly increase in height; so that from this second bridge to the water, there is the astonishing height of two hundred and eighty feet. The highest tower in Spain, the Giralda, in Seville, or the Monument, near London Bridge, if they were placed on the water, might stand under this stupendous arch, without their tops reaching to it."

"The mode of constructing this bridge is no less surprising than the situation in which it is placed, and its extraordinary elevation; it is a single arch of one hundred and ten feet in diameter; it is supported by solid pillars of masonry, built from the bottom of the river, about fifteen feet in thickness, which are fixed into the solid rock on both sides, and on which the ends of the arch rest; other pillars are built to support these principal ones, which are connected with them by other small arches. But as it is difficult to describe such an edifice, I must refer to the sketch I have made of it." (See the Cut.)

"A bridge was built on this spot in 1735, but the key-stone not having been properly secured, it fell down in 1741, by which fifty persons were killed. The present bridge was finished in 1774, by Don Joseph Martin Aldeheula, a celebrated architect of Malaga; and appears so well constructed as to bid defiance almost to time itself."

"It is impossible to convey an adequate idea of it: from below it appears suspended in the air; and when upon the bridge, the river beneath appears no longer a mighty torrent, but resembles a rippling brook. When standing on the bridge, the optical delusion is very singular: the torrent of water appears to run up a hill towards the bridge, and the same phenomenon takes place when viewed in either direction."

"One of the streets of the city is built almost close to the edge of the precipice, and stairs are hewn out of the solid rock, which lead to nooks in the lower precipices, in which, though there is very little soil, gardens have been formed, where fig and orange trees grow with considerable luxuriance, and greatly contribute to the beauty of the scenery. From the situation of Ronda on the top of a rock, water is scarce, and stairs are constructed down to the river, by which means the inhabitants are supplied. We descended by one flight of three hundred and fifty steps, and at the bottom found a fine spring, in a large cave, which, after turning a mill at its source, contributes to increase the waters of the Guadiaro. From this spot, our view of the lofty bridge was most striking and impressive, and the houses and churches of the city, impending over our heads on both banks, had a most sublime effect. Beyond the bridge, the river takes a turn to the right, and passes under the Alameyda, from which, the precipice of five hundred feet is very bold and abrupt, though interspersed with jutting prominences, covered with shrubs and trees".

FINE ARTS

STATUE OF MR. CANNING

This colossal bronze statue to the memory of George Canning, has lately been placed in Old Palace Yard, Westminster; the cost being defrayed by public subscription. The artist is Mr. Westmacott. The figure is to be admired for its simplicity, though, altogether, it has more stateliness than natural ease. The likeness is strikingly accurate, and bears all the intellectual grandeur of the orator. Some objection may be taken to the disposal of the robes, and the arrangement of the toga is in somewhat too theatrical a style. We should, at the same time recollect, that the representation of a British senator in the costume of a Roman is almost equally objectionable. It would surely be more consistent that statues should be in the costume of the period and of the country in which the person lived. We know this will be opposed on the score of classic taste, which, in this instance, it seems difficult to reconcile with common sense.

The statue is placed on a granite pedestal, and stands within a railed enclosure, planted with trees and shrubs, and adjoining the footway of Palace Yard. The bronze appears to have been tinted with the view of obtaining the green rust which is so desirable on statues. The effect is not, however, so good as could be wished: the green colour being too light, and at some distance not sufficiently perceptible from the foliage of the trees which rise around the figure.

The situation of the statue has been judiciously chosen, being but a short distance from the senate wherein Canning built up his earthly fame. The association is unavoidable; and scores of patriotic men who pass by this national tribute to splendid talent may feel its inspiring influence. Still, rather than speculate upon Mr. Canning's political career, we quote Lord Byron's manly eulogium on the illustrious dead: "Canning," said Byron, in his usual energetic manner, "is a genius, almost an universal one, an orator, a wit, a poet, and a statesman." Again,

Yet something may remain, perchance, to chimeWith reason, and what's stranger still, with rhyme;Even this thy genius, CANNING! may permit,Who, bred a statesman, still was born a wit,And never, even in that dull house, could'st tameTo unleaven'd prose thine own poetic flame;Our last, our best, our only Orator,Ev'n I can praise thee.It may be interesting to observe that the colour so much admired on bronze statues is fine dark green from the oxide formed upon the metal, which, being placed without doors, is more liable to be corroded by water holding in solution the principles of the atmosphere; "and the rust and corrosion, which are made poetically, qualities of time, depend upon the oxydating powers of water, which, by supplying oxygen in a dissolved or condensed state enable the metal to form new combinations."—Sir H. Davy.

THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

RHYMING RUMINATIONS ON OLD LONDON BRIDGE

Oh! ancient London Bridge,And art thou done for?To walk across thee were a privilegeThat some unborn enthusiasts would run for.I have crossed o'er thee many and many a time,And hold my head the higher for having done it;Considering it a primeAnd rare adventure—worthy of a sonnetOr little flight in rhyme,A monody, an elegy, or ode,Or whatsoever name may be bestowedOn this wild rhapsody of lawless chime—When I have done it.How many busy hands, and heads, and hearts—What quantities of great and little peopleAs thick as shot;Some of considerable pride and parts,And high in their own eyes as any steeple,Though now forgot!How many dogs, and sheep, and pigs, and cattle,How many trays of hot-cross buns and tarts,How many soldiers ready armed for battle,How many cabs, and coaches, drags, and carts,Bearing the produce of a thousand marts,How many monarchs poor, and beggars proud,Bishops too humble to be contumacious;How many a patriot—many a watchman loud—Lawyers too honest, ay, and thieves too gracious:In short, how great a numberOf busy men—As well as thousand loads of human lumberHave past, old fabric, o'er thee!How can I thenBut heartily deplore thee!Milton himself thy path has walked along,That noble, bold, and glorious politician,That mighty prince of everlasting song!That bard of heaven, earth, chaos, and perdition!Poor hapless Spenser, too, that sweet musicianOf faery land,Has crossed thee, mourning o'er his sad condition,And leaning upon sorrow's outstretched hand.Oft, haply, has great Newton o'er thee stalkedSo much entranced,He knew not haply if he ran or walked,Hopped, waddled, leaped, or danced.Along thee, too, Johnson has sideways staggered,With the old wolf inside of him unfed;And Savage roamed, with visage lean and haggard,Longing for bread.And next in note,Dear worthy Goldsmith with his gaudy coat,Unheeded by the undiscerning folks;There Garrick too has sped,And, light of heart, he cracked his playful jokes—Yet though he walked, on Foote he cracked them not;And Steele, and Fielding, Butler, Swift, and Pope—Who filled the world with laughter, joy, and hope;And thousands, that throw sunshine on our lot,And, though they die, can never be forgot.These comets of their dayHave passed away,Their dust is now to kindred dust consigned;Down at death's knees e'en they were forced to bow,Yet each has left an honour'd name behind—And so, old bridge, hast thou;Thou hast outlasted many a generation;And well nigh to the last looked well and hearty;Thou hast seen much of civil perturbation,And hast supported many a different party.Yet think not I deride:Many great characters of modern days,(The worthy vicars of convenient Brays)Have thought it no disgrace to change their side.And yet now many a luckless boat,How many a thoughtless, many a jovial crew,How many a young apprentice of no note;How many a maiden fair and lover true—Have passed down thy Charybdis of a throat,And gone, Oh! dreadful Davy Jones, to you!The coroner for Southwark, or the City,Calling a jury with due form and fuss,To find a verdict, amidst signs of pity,In phrase poetic—thus:—"FoundDrown'd!"Monthly Magazine.

TRUE STORIES OF MAGIC IN THE EAST

By Charles Macfarlane, EsqWhen that enterprising, intelligent, and inquisitive traveller, Mr. R– was travelling in Egypt some few years ago, his curiosity was excited by the extraordinary stories current about magic and magicians, and by degrees, despite of a proper Christian education, he became enamoured of the secret sciences. He even made some advances in them, under proper masters, and would have made more, had he not met an Italian who was supposed to be a proficient in the learning of Egypt. But this worthy bade him look at his worn body, his haggard, harrowed countenance, and awfully warned him, as he valued quiet days, and slumbering nights, to shun the dangerous pursuits in which he had engaged. Mr. R– took his advice, and thought little more of the matter, until some time after when he was staying with his friend Mr. S– at the – consulate at Alexandria. Mr. S– almost as intelligent a gentleman as Mr. R–, had lost some silver spoons, and it was determined perhaps to frighten the servants of the house into confession, or perhaps, (and what is just as likely,) for a frolic and the indulgence of Mr. R–'s well known curiosity, to summon a conjuror, or wise man. There happened to be a famous magician, lately arrived from distant parts of Africa, then at hand, and he came at their call. This man asked for nothing but an innocent boy under ten years of age, a virgin, or a woman quick with child. The first of the three was the easiest to be procured, and a boy was brought in from a neighbouring house, who knew nothing at all of the robbery; in case his age should not be guarantee sufficient, a sort of charm was wrought, which proved to the professor's satisfaction that he was free from sin. The magician then recited divers incantations, drew a circle on the floor, and placed the boy, who was rather frightened, in the middle of the circle. Other incantations were then muttered. The next thing the magician did, was to pour a dark liquid, like ink, into the hollow of the boy's hand; he then burned something which produced a smoke like incense, but bluer and thicker, and then he desired the boy to look into the palm of his hand, and to tell him what he saw. The boy did as he was bid, but said he saw nothing. The magician bade him look again; this second time the boy started back in terror, and said he saw in the palm of his hand a man with a bundle. "Look again," said the magician, "and tell me what there is in the bundle."

"I cannot see," said the boy, renewing the investigation, "but stop," he added after a moment, "there's a hole in the handkerchief, and I see the ends of some silver spoons peeping out!"

"Look again—look again, and tell me what you see."

"He is running away between my fingers!" replied the boy.

"Before he goes describe his dress, person, and countenance."

The boy looked again into his hand.

"Ay, tell us how he is dressed," cried Mr. S–, who had become more than half serious, and anxious to know who had purloined his spoons.

The boy turned his head immediately and said,

"He is gone!"

"To be sure he is," said the necromancer angrily, "the Christian gentleman has destroyed the spell; tell us how he was dressed?"

"The man with a bundle had on a Frank coat and a Frank hat," said the boy unhesitatingly—and here his revelations ended.

Though much mollified at the interruption of which he had been the cause, Mr. S– had the satisfaction to learn that his plate had not been stolen by an unbelieving Egyptian or Arab, but by a Christian and a Frank, and, with his friend Mr. R– to enjoy the conviction, that in the singular scene they had witnessed there could be no collusion, as the innocent boy (they were certain) had never seen the necromancer until summoned to the – consulate to make a looking-glass of his hand.

Some recent French publication has trumped up a story about Bonaparte and the magicians, when that extraordinary man was in Egypt, and separated from the fair Josephine, who was then, though his wife, supposed to be the object of his amorous affections; and they make the conqueror—the victor of the battle of the Pyramids, turn pale, and then yellow with jealousy, at the revelations which were made to him by the wise men of Egypt. But besides the characters of Napoleon and of Josephine, I have other grounds (not necessary to explain here) for believing that the whole of this incident, is but a parody of the following well known story.