Полная версия

Zinka

Zinka

Tatiana Koroleva

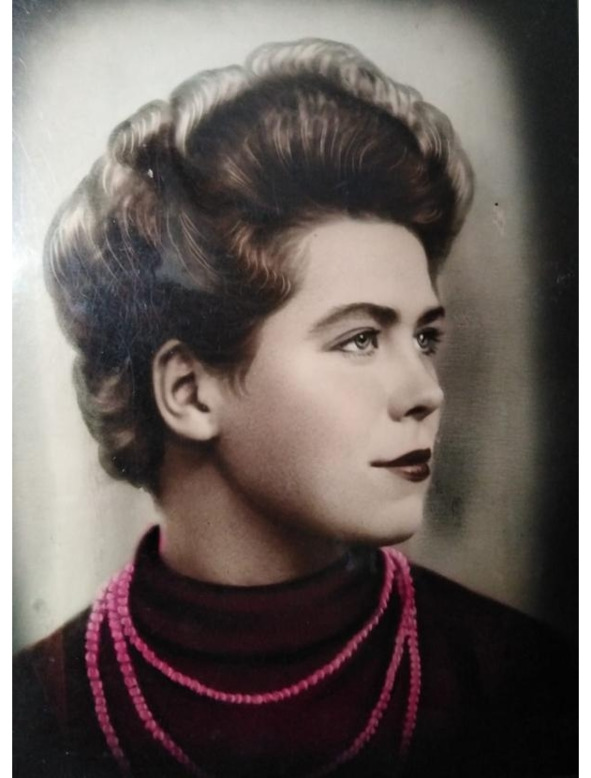

Devoted to my mother Zinaida

© Tatiana Koroleva, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0067-9232-6

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

Part 1

What Was It Like

Chapter 1. The Bell Tower

The July heat made it difficult to breathe deeply. It was so hot that the water scoop, which had been hanging on a rusty barrel in the corner of the garden since Adam was a boy, burned the hands of anyone who passed by and scooped up the pitiful remains of rainwater that had run off the roof since the last rain at the end of June. You scooped up some water, splashed it on your face, and it seemed easier to breathe.

Vera had a lot to do that day. When did she ever not? From morning till night, she was busy as a bee, either around the house or in the garden. The garden was large and well-tended. It was time to hill the potatoes again, but you couldn’t get Grisha to do it. From morning till night, he was at the village council. Look at that! He was appointed the chairman of the collective farm. Oh well… There would be plenty of cucumbers, but in winter they’d all be swept away by the potatoes. She sighed heavily, looked up at the sky, and adjusted her kerchief, which had slipped down onto her forehead. If only there were a cloud…

The sky was high, the air was thick, like hot soup from the oven. It was time for Zinka to wake up; she had been sleeping for two hours after lunch. The village was quiet; the children had run around in the heat and dust. They were fast asleep after a plate of soup made from last year’s sauerkraut. They also drank a mug of milk with a crust of yesterday’s bread. They were full, and that was fine. Let them sleep. While they slept, Verka would do some chores and prepare something for dinner. She had to water the greens, but it was still too hot, so she couldn’t. In the evening, the neighbour’s boys would fetch water, and she would water the greens. Let them sleep… What could you do, there hadn’t been a war for a year then, thank God. They had to be patient, everything would work out, she was sure…

A pleasant coolness met Vera in the mudroom. Zinka’s old doll, which Vera had sewn from Grisha’s old trousers herself, fell at her feet. It was strange, Zinka always carried it with her. And she always slept with it in her arms. How strange it seemed. It was lying right in front of the doorstep in the mudroom. What was wrong with her? Maybe she was growing up? She was growing like grass. She would be three soon. How quickly time flew.

“Verka!!!! Verka!!!! Oh, my goodness!!!!! Oh, my God!!! Verka! Damn you! Where are you????

Vera’s heart sank. Zinka… She rushed into the house, pulled back the curtain – the boy was sleeping sweetly, sprawled on the floor on an old quilted blanket. Zinka was not in bed, as if she had vanished into thin air. Oh… She rushed to her neighbour’s piercing scream, her heart pounding loudly in her throat, her ears ringing.

Ninka rushed into the porch, kicked Zinka’s doll with her foot and, grabbing Vera by the sleeve, dragged her onto the porch.

“Oh, Verka, let’s run! She’s in the bell tower, the fool! She’s climbed up, but she’s afraid to climb down, she’s crying like a fool. And there’s no one to get her down – all the men are in the fields. What should we do?”

The old church gleamed white at the end of the village. It didn’t seem far away. But Vera’s legs wouldn’t carry her, she couldn’t run. Tears streamed down her face; her heart pounded in her throat. Lord, help me…

And a man was found. And Zinka was taken down. What a mess! She’d get it from her father…

Chapter 2. To School

“I’m not going! You go yourselves!” Zinka was crying in the evening, smearing tears across her dusty face. She had been running around all day with the village children and was soaked to her underwear.

“She’s not going! Who will go to school for you? Your father? Or maybe the shepherd Mikitka? Now get undressed quickly and run into the washtub, I’ll pour water over you, there’s still warm water left in the bucket.”

Vera pulled the dress off her daughter and pushed her towards the washtub. Her hair was wet, her head sweaty from running. Zinka resisted, pushing and getting stubborn.

“I’ll do it myself, leave me alone!”

Vera washed her daughter, who was already half asleep. She put her in a nightgown – her head barely fit through the neck. The girl was growing up; in the morning she would go to school.

The school was in another village, five kilometres away. Every morning, the children walked in a group along a short path through the field and the distant forest. In winter, the path was smooth and well-trodden, so they walked along it. In the morning, they walked one after another, half asleep. And after school, they laughed loudly, joked, imitated their teacher, and played snowballs. Or they just fooled around and rolled in the snow. The whole way to school took about forty minutes, but when the whole gang was fooling around, it took a good hour.

In the March thaw, children had to go around a ravine with meltwater for a whole mile. The water in the river also rose, flooding the old bridge, over which the children jumped from log to log, laughing and swearing.

Zinka did not like winter. It was dark in the morning, and the road through the woods was scary. The only thing that saved her was the children nearby. One would grab her, then another would lend a hand. And so, they walked. And the days were short. In the morning, it was dark when she left, and when she returned from school, it was dusk again.

The school in that village was small, with only one class. Their teacher, Zoya Vasilievna, met the children on the school porch wearing a shawl thrown over her shoulders and holding a broom in her hand. They used this broom to sweep the snow off their boots. The older children did it themselves, but Zoya Vasilievna always helped the little ones.

“Stop, don’t fidget! Look how much snow you’ve brought onto the porch!”

Zinka quickly and efficiently put her kirza boots under the teacher’s broom, sniffing. The girl was sent to first grade in kirza boots. Warm socks in winter. Grandmother Agafya knitted them. It was okay, the main thing was that they didn’t get wet, and that was fine… It was 1950. The country was rising from the ruins.

“Well, children! Who will tell us a fable, who is our hero?”

Zinka almost jumped out of her trousers, bouncing on the bench behind the crooked desk with her hand raised. She shook her hand and hissed like a kettle on the stove.

“Not ready again? Zinochka, come to the blackboard and tell us!”

Zinka rushed cheerfully to the blackboard with seven-league strides, tripping over her classmates’ bags and getting a couple of pokes in the back from them. And, before reaching the blackboard, she turned sharply towards the class, raised her hand in a theatrical gesture and shouted:

“Cock-a-doodle-doo!”

Zoya Vasilievna turned her head towards Zinka in amazement. The class burst out laughing.

All the way home, the children were running in front of Zinka, backing away and laughing, repeating in different voices:

“Cock-a-doodle-doo! Cock-a-doodle-doo!” And Zinka was so upset that they were laughing at her. Well, never mind! She would show them…

Chapter 3. The Older Brother

Grisha, Zina’s father, did not go to that war – they did not take him. He had been shot up in Finland war, and the military commissariat decided not to draft him, to leave him, so to speak, on the front line in the rear as the chairman of the collective farm – to command the women.

At the very beginning of the war, Vera and Grigory had a baby boy. He was chubby-cheeked, plump, and creamy. He had a good appetite. Nickolay, Kolka, son. Vera could barely cope, torn between the collective farm and home. Grisha was a poor helper, being the chairman. He had plenty of his own worries. He spent whole days at the village council, or he would go to the city to report to his superiors.

Food was very scarce in the 1940s. Everyone survived on their own farm. Grigory had a small apiary, inherited from his father. A cow, a piglet and a dozen chicken. They exchanged food in the village. You give me a couple of eggs for pancakes, and I’ll give you a jug of milk. They didn’t see any meat for months. Honey helped a lot. If it weren’t for the apiary, they would have been in real trouble. They survived thanks to honey.

Zinaida was born a couple of years after her brother Kolka, in 1943. A child of war. Her brother loved Zinka. That summer, when she climbed the bell tower, he was already five. Kolka hung out with older boys, running around the village all day long. Zinka often cried. She asked to go with Kolka.

“Take her, Nikolai, you can look after her at the same time. Mum needs to work in the field,” Vera asked her eldest son. Of course, he would look after her, who else would!

He would take his father’s sheepskin coat and turn it inside out. He would put it on, get down on all fours and growl, walking towards Zinka as if he were a bear in the forest. Zinka would burst into tears, squeal and smear snot across her cheeks. Vera would hit Kolka on the back with a towel so that he wouldn’t scare his sister to death!

Or Kolka liked to tease Zinka. He would get the boys to join in, and they would all shout together:

“They bought Rubber Zina in the shop! They brought Rubber Zina in a basket!”

“I’m not rubber!!!! They haven’t brought me in a basket!” Poor Zinka ran after them, crying her eyes out, smearing tears across her face. That was how brother Kolka and sister Zinka grew up. Sometimes hugging each other, sometimes in different corners of the house.

It was April, and the last snow remained as spring frost only in the ravine through which the children walked in their usual crowd to school. Kolka secretly took an old axe from his father’s barn and on the way to school stuck it into a birch tree on the edge of the village. He placed a jug under the wound to catch the birch sap. When they went back, the sap would have already started flowing. On the way home from school, Zinka remembered the birch tree and ran to it faster than anyone else. She ran up, threw herself against the trunk with her hands, and the axe fell out. The blade cut right through her leg. It cut her boot and left a deep wound. And there was blood, like from that piglet they had slaughtered the other day. The children were terrified. Oh, Kolka would get some from his father for taking the axe without permission, for not looking after his younger sister. He was always to blame in their eyes. Because he was the older brother. What could you do?

Chapter 4. A New Life

Grigory had been saying more and more often lately that life in the city was better, simpler.

“It’s time for us to go to the city, Vera. They’ve started giving passports to collective farm workers, so there’s no reason not to go.”

“Grisha, just leave everything behind? What about the house? The garden? The children are at school. And me? What will I do there, in your city? I’m used to the land, to the village.”

“We’ll move the house, log by log. I’ve already found a place and made an agreement with the men from the cooperative; they’ll do it for a reasonable price. We need to decide, Vera. It will be easier for us there. You’ll have your garden, and the school will be nearby. Is it good that the children have to walk five kilometres to school?”

Grisha had those conversations with his wife more and more often. And finally, he persuaded her. Oh, how frightening it was for Vera to start a new life. She wanted to consult with someone. But who could she ask for advice? The village women at the well would immediately wave their hands, get alarmed, and start trying to dissuade Vera. What did they know about a new, city life? Had they ever tried it? Grisha had. Sometimes he would stay late at the office with his bosses and spend the night at their place. There was running water and a warm toilet. He envied how city people lived.

Grigory forbade Vera to share her doubts and seek advice from anybody. He forbade it completely. Not a word! And who would like it if the chairman of the collective farm ran away from his post? But he had decided everything long ago and discussed it. They found him a job in the city and helped him move. The world is not without good people. Besides, Grigory knew how to form bridges and think everything through in advance. Life had taught him wisdom.

They packed their things quietly, on the sly. It was 1953, and winter was coming to an end. The cold and snowstorms were receding, giving way more and more to the sunny days of late February and the drizzle of early March. Kolka had no idea why the whole house was full of bundles and sacks. He came home from school, threw down his bag and ran outside to play with the village boys. He barely had time to eat. But Zinka was attentive and curious from childhood. She would ask a hundred questions and wouldn’t let up until she got a clear answer. A real pain in the neck! She turned ten. A wonderful and smart girl was growing up.

“Mum, why are you putting everything in bags? You took all our clothes out of the chests. Are you giving them away? Or why? Huh?”

“Your father and I are renovating, Zinochka. Renovating!” We’re going to whitewash the stove, and there’s a lot of painting to do. Everything will get dirty. That’s why I’m putting it away. Go on, Zinka, go and play. Don’t bother your mother! Don’t get underfoot!”

The day before the move, Zinka and Nikolai’s parents sent them to spend the night at Grandma Agafia’s. The men from the cooperative arrived and quietly dismantled their small house log by log in one night. They all pitched in, and the house was gone. Only the stove in the middle glowed white in the night. The moon was bright, providing light for their work. The village slept. Zinka and Nikolai slept on the stove at Grandmother Agafia’s house. A new life awaited them. A city life.

Chapter 5. At Grandma Agafia’s

An annoying fly prevented Vera from cleaning the pot with sand outdoors until it shone, as she liked to do. She waved the fly away with her wet hand, but the fly kept coming back, buzzing and buzzing. It kept trying to get into her eyes or crawl along her sweaty cheeks. The pest was persistent! Vera straightened up, groaning. Her back had been hurting for two months, ever since she moved. She rinsed the pot thoroughly from the barrel and hung it upside down on the fence. The pot was shiny and looked new. Sand was a good cleaning agent, a pleasant chore. A ray of sunlight reflected off the pot and into Vera’s eyes. Vera was pleased.

She looked back at the house. Wow, it was standing there as if they never left. Grigory had the men dig the foundation to the right size ahead of time. He chose a good place for the house. It was like a city, but not quite. It was on the very outskirts. There was a piece of land for a vegetable garden and a water tap nearby in the street. Wow! You turned the handle, and water flew into an old rusty bucket. It was time to buy a new bucket; it was already embarrassing.

Yes, Grisha was right. City dwellers lived comfortably, and easier. The school was a ten-minute walk away. It was big, bright, three stories high. And the teachers were so cultured, reserved, smiling at Zinka and her mother. Grisha was right, Vera was wrong to argue and doubt. She worried for nothing. Everything would work out little by little. There was no war, and that was fine…

Zinka liked her new life. The house was the same, familiar to her, the school was nearby. She didn’t have to get up at dawn and trudge through the ravine and the distant forest to get to class. The teacher was also good and kind. Zinka made friends, one of whom, Katya, came from the same village as Zinka. They lived in different streets there, but here, in the city, they lived right across from each other. So, they walked to and from school together.

When the friends got older, in fifth grade, after school they sometimes walked together to the village, seven kilometres away, across a distant field and a small forest.

“Katya, shall we go to Grandma Agafia’s after school today? It’s Friday, she’s cooking sour cabbage soup and has put the dough on.”

“Let’s go! My parents have gone to Moscow today to buy sunflower oil and sugar. They’ll be back late. I’ll have lunch there,” Katya was glad that she wouldn’t have to stay alone at home that day, bored and waiting for her parents to return from Moscow.

Grandma Agafia’s cabbage soup was special. No one else could cook sour cabbage soup so deliciously. It simmered on the stove for a long time on the cooling embers of birch wood. The embers sometimes shot up and landed in the cast-iron pot. And that made the soup even tastier and more filling.

So, the two girls would run through the forest to their grandmother’s village after school. They weren’t afraid of anything. And their parents didn’t scold them; they used to it. And Grandma Agafia was happy too – she was delighted with her granddaughter.

“Hey! Make some pancakes with holes in them, okay? Sour ones! And with sour cream!”

“What do you mean, with holes? On a leaven? Do you like your grandmother’s pancakes? Your mother won’t make you any like that.”

“Why wouldn’t she make them? She bakes delicious pancakes. But for some reason, everything you make is the most delicious, Granny, both the cabbage soup and the pancakes. And I’m always hungry by the time I get to you.”

In the summer, Vera would send Zinka to stay with her grandmother Agafia. Nikolai also spent the summer vacation with his sister at his grandmother’s, but reluctantly. He was already a teenager. They had fun at their grandmother’s in the summer. They walked from dawn to dusk and were hooligans. Zinka loved especially running barefoot through puddles after a summer thunderstorm, squealing with delight. The ground was warm and soft. There were no worries in her head.

“Oh, Zinka, what’s that moving in your hair?”

“Mummy, Kolka. What is it? Don’t scare me!” Zinka jumped and squealed, feeling something crawling and buzzing in her hair.

“Stop, don’t move, you fool! Wait, I’ll swat it!” Nikolai took a stick the size of a club, swung it and hit Zinka on the head. Of course, he hit the hornet, but at the same time, Zinka fell silent. On the grass. With her eyes rolled back.

“Oh my God, you killed her, you fool! Holy Mother of God! Zinka, Zinka!” Kolka’s friend yelled. “Hey, Zinka, get up, what’s wrong? I was just kidding… Zinka!” Frightened Kolka shook his sister’s shoulder.

Zina opened her eyes and, looking around, raised her hand to the place where it hurt badly. She felt a huge bump. And she quietly whimpered in pain.

“I’ll tell Dad everything, you idiot!” Zinka shouted and cried even harder. The boys around her breathed a sigh of relief. Zinka was alive!

In the village where the children used to go to school, there was a small club. Every weekend, they would bring a film to this club. Residents from neighbouring villages would flock to the cinema. Kolka and his friends also went to that club. Zinaida often asked to go with him.

“Kolya, are you going to the cinema today? Kolya, can I come too? I don’t want to sit with my grandmother all evening. It’s boring. All my friends are going, so take me too. Please take me!”

“You’re so annoying! Let your older brother go out! Why are you always following me around? Grow up already!” Kolka complained every time, but he took Zinka with him anyway.

“Kolya, do you want me to teach her quickly not to tag along with us?” Nikolai’s friend suggested it once.

“Yeah, you don’t know her very well! She has a temper! She takes after her father – everyone says so. She’s as stubborn as a bull!”

The club was on the edge of the village, and you had to walk past the cemetery to get there. They went there in the summer when it was still light, but they had to return when it was already dark. They walked in a large crowd, discussing the film, laughing, and eating the seeds left in their pockets after the film. And no one even thought to be afraid of the cemetery. But on that day, Nikolai’s friend ran a little ahead, threw an old sheet over his head, and jumped out at Zinka. The whole crowd screamed and scattered in different directions. The whole crowd. Everyone except Zinka. She stood rooted to the spot, clenched her fists, and froze.

“Yeah, you think I’m scared? Not a bit! You fool! You’re stupid – consider yourself crippled! I’ll tell my father – he’ll deal with you quickly! It was my Kolka who put you up to this. I heard you in the hallway. You don’t want me to go to the club with you. Big deal… I’ll ask some adults to take me with them; I don’t need you very much!” Zinka declared proudly, her voice trembling with indignation.

Chapter 6. The Goddess

Years passed, and life went on as usual for Vera and Grigory’s family. Zinka and Nikolai grew up, their parents worked tirelessly, raising their children and managing the household. They no longer moved the apiary from that village, leaving the beehives with their relatives. Vera’s vegetable garden was smaller and more modest, with four garden-beds and a small potato plantation, more for her own care than for winter supplies.

Zinka was a good student. She was especially good at maths. She enjoyed going to school, and she was always sociable, cheerful, but a little noisy. She loved justice very much. If Zinka saw someone hurting someone else, she would immediately intervene. Otherwise, she might even slap them. Zinka had a heavy hand.

The children would walk down the street after school. They would come home from school, throw their schoolbags in the far corner and go for a walk. In winter, they would go to the ravine, where the local men would build a hill for the children on the slope when the first frosts came. Zina and her friends spent all their time there. And in the warm season, they would play Cossacks and Robbers, Stand-Stop, Hali-Halo, and Bouncers. What games they played in their childhood! The children would run around with a ball until they were exhausted, then they would all go to Zinka’s bench by the gate. The bench was large and wide. It was comfortable, with a backrest, the centre of the universe. The children would gather around it and play quiet games to rest a little and catch their breath. Sometimes they played ring-around-the-rosy, sometimes they played tag, sometimes they played edible-inedible. And who knows what else. The days were long in summer, it got dark late, and there was no need to get up early in the morning. Why not play?

And so, several years flew by. Zinochka finished eighth grade and, together with her friends, went to a professional college for a large factory in the city. She studied during the day and met friends in the evenings, and they all went out for walks together. And among those friends and neighbours there was one boy, tall, blue-eyed, with a dimple on his chin. Very handsome. He kept glancing at our Zinochka. And why not? Zina had become such a beauty by the age of fifteen. She was tall, with long, thick hair and dimples on her cheeks. When she looked up, her eyes were like lakes… In a word, she was a goddess! Our Anatoly fell madly in love with Zinaida…

“Hello, goddess! Would you like to go for a walk today?” Anatoly decided to ask her out on a date. Her cheeks flushed, and sweat appeared on her forehead.

“Of course, I’ll go! Who else is coming?”

“Who else do you need?”

“Just the two of us? Why not all together? Katerina is already back from school, and many others are already at home.”

“Zin, do you really not understand, or are you pretending?” Anatoly plucked up his courage and blurted out. His heart was pounding like a bell in his chest, and his palms were wet. “I’ve loved you for a long time, but I was afraid to say so.”

Zinka listened, embarrassed, her head bowed, rolling a pebble back and forth in the sand with her shoe. “Let’s go!” she said, raising her head proudly and shaking her hair dashingly.

From that day on, it became a habit – Zinka would rush home from college after classes, and Tolya would meet her. In any weather, he would run to meet her with pleasure and joy.