Полная версия

The Spark of Time. How Meaning Transmutes Worlds

The Spark of Time

How Meaning Transmutes Worlds

Sergey Antonovich Kravchenko

Dedicated to A. P. Levich

© Sergey Antonovich Kravchenko, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0067-9014-8

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

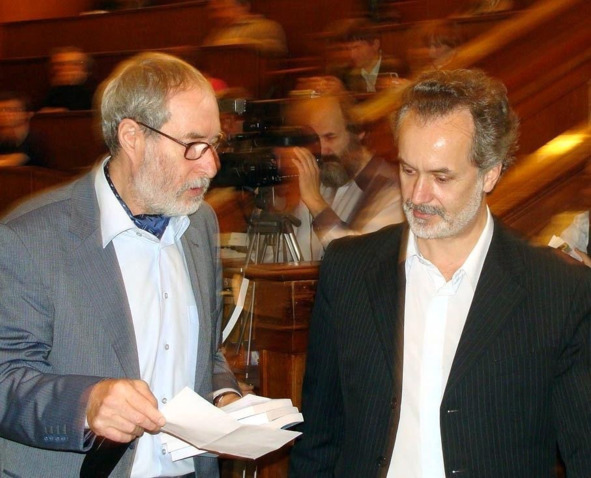

Alexander Petrovich Levich and Sergey Antonovich Kravchenko. Photo by Yuri Alexandrovich Lebedev, 2010

About the Book

Annotations

1. Brief (for cover/catalog)

The Spark of Time is a book about how meaning shapes destiny. At the crossroads of science, philosophy, and personal experience, the author explores the nature of time, foresight, and altered states of consciousness.

2. Popular (for a broad readership)

The Spark of Time is a small luminous point in the history of our consciousness. This book tells how meaning and images become events, how altered states of consciousness (ASCs) open doors to other dimensions of time, and why foresight may be not a miracle, but a practical capacity.

3. Scientific-popular (for those interested in the future of science and culture)

What will change if we understand time more deeply? The Spark of Time shows that knowledge of the nature of time can transform science, culture, and human existence itself. Precognition, ASCs, quantum hypotheses, and new scientific methods converge here in a project of the future, where humanity learns not only to measure time but also to interact with it.

4. Academic (for specialists)

The author offers an interdisciplinary analysis of the phenomena of time, foresight, and altered states of consciousness. In dialogue with philosophy (Plato, Bergson, Jung), cognitive science, and psychotherapy, he formulates the concept of the «conversion point» and the working hypothesis of the «temporal crystallization condensate» (TCC) – a special informational-neurophysiological phase where structures of meaning obtain a statistical connection with future events. Methods (autogenic training, mask therapy), verification protocols, and proposals for experiments are presented.

5. Methodological (on new scientific methods)

The Spark of Time also raises the question of new methods of inquiry. How do we study unique cases – foresight, dreams, the destinies of individuals and societies – if classical science demands repeatability? The author proposes the foundations of a «new science of time,» where preregistration, living registries, and cognitive protocols matter. The book opens a path toward a philosophy of science oriented toward the unique and the future.

6. Literary-philosophical (on the meaning of the book as a text)

This book is not only a study but also a confession of a seeker. The Spark of Time is a path between reason and imagination, where meaning becomes the breath of the world and time reveals itself as the mirror of the soul. At the crossing of science and myth, philosophy and personal experience, a new understanding is born: time is a companion, a guide to eternity.

7. Personal (from author to reader)

This book was born out of my encounters with time – in dreams, in dialogues with patients, in scientific debates, and in the silence of autogenic training. I wrote it both as a researcher and as a man for whom time is a living reality, full of pain and hope, loss and revelation. These pages contain my experience, my questions, and my sparks of hope. I invite you to enter the conversation: about the future, about meaning, about our human destiny.

Unlocking the Dimensions of Time: A Journey into Temporal Psychology and Consciousness Forecasting

Editorial Introduction by Sergey Kravchenko (assisted by AI)

In this groundbreaking work, psychologist and consciousness researcher Sergey Kravchenko invites readers to explore the intricate interplay between past, present, future, and the eternal. Drawing on decades of practice in altered states of consciousness (ASC) and temporal psychology, Kravchenko presents a methodical yet deeply intuitive approach to understanding how the human mind perceives and anticipates time.

This book is not just a study of psychic phenomena or theoretical frameworks – it is a practical guide to registering, analyzing, and interpreting precognitive signals, bridging science, philosophy, and lived experience. Through meticulously documented case studies, including rare and non-replicable events, readers will gain insight into the rigorous methodology that transforms seemingly elusive foresight into verifiable, meaningful knowledge.

For anyone intrigued by the frontiers of consciousness, the science of time, and the art of anticipation, this book offers a unique lens to understand how our minds navigate the continuum of existence – and how we can learn to engage with the future before it unfolds.

Introduction

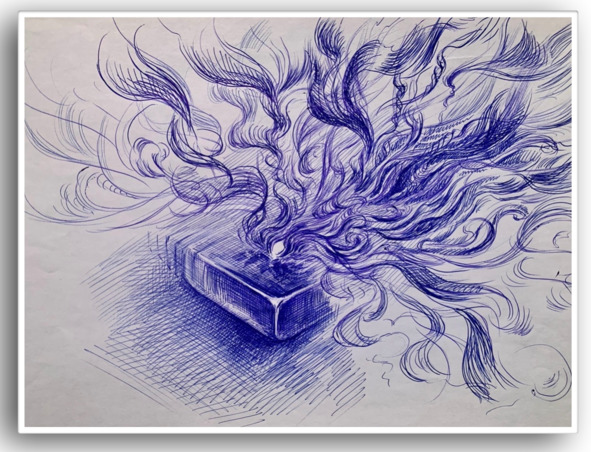

All my life, time has been for me not only a theoretical question – it has come as an experience. More than twenty years ago, in a half-dream, I received a vision that has since become the axis of my reflections and practices. I saw not a line of clocks and calendars, but a fold of space where two worlds coexisted: the material world – with things, events, bodies – and the world of images – ideal, Platonic, composed of meaning and archetypes. Between them glimmered a small spark, like the light of a candle. This was not merely a symbol: within it an exchange occurred – ideas were transmuted into material entities, and matter, as in a forge, generated images and concepts. This process was continuous, akin to metabolism in a living organism; every movement of meaning resonated in the world of events, and every event bore within itself the seed of an image.

Two worlds: the material world and the world of images, consisting of meaning and archetypes. Between them, a small flame glowed, like from a candle.

Later, again in a half-dream, another simple yet important distinction opened to me: in our experience, there are two senses of time – the measurable (what clocks and instruments register) and the immeasurable (what we live as duration, meaning, kairos). They coexist within each of us and at times come into conflict: one gives us planning, agreement, and order; the other – depth, intuition, and the possibility of seeing the world not only as a sequence of events but as a fabric of meanings. On the border of these modes, special states emerge – thresholds where the sense of time alters its nature.

In my clinical practice, and in working with people who came to me for help, I encountered yet a third form – timelessness. This is the experience when the usual supports of past and future vanish; not Platonic eternity, not an ordered «forever,» but a state in which meanings blur and the personality temporarily loses its foothold. Patients described such experiences as «falling out» of time, and for some it became traumatic – they lost orientation, shielded themselves with rituals, or enclosed themselves within dogmas. Understanding timelessness, its nature, and safe ways of leading people out of it became an important part of my therapy: from this arose methods of support and integration – including mask therapy, which helps restore the boundaries of the «I» during intense ASC experiences.

My years of practice – autogenic training since the age of twenty, long psychotherapeutic work, seminars and clinical cases – went hand in hand with scientific and organizational efforts. I collaborated with the Institute for the Study of the Nature of Time under the direction of Alexander Petrovich Levich and was the initiator of the International «Center for Anticipation» (2008—2018). There we built databases, discussed methods for testing foresight, and sought a balance between empiricism and cautious interpretation. All of this – diaries, ASC records, collective discussions – became material for this book.

In the present work I attempt to summarize many years of experience and knowledge and to move further: together with the tools of artificial intelligence I formulate a working hypothesis that I call the temporal crystallization condensate (TCC). TCC is both an image and an experimental idea: a local phase of ordering, when structures of meaning and neurophysiological coherence create conditions in which an image may acquire a connection with a probable future. I do not claim a final formula; I propose a hypothesis, describe a methodology for testing it – recording protocols, verification criteria, neurophysiological metrics – and invite colleagues in science and practice to collaborate.

In this book I weave together several layers: personal experience and the observations of a therapist; philosophical reflections on time (from Plato to contemporary thinkers); scientific data on the perception of time, brain rhythms, and altered states of consciousness; and methodology – how to record, how to test, how to work ethically with information about the future. I address both the general reader and the specialist: the one who wishes to understand what is happening within him in a state of inspiration or anxiety, and the one who studies time in the laboratory, writes papers in cognitive science, or develops technologies related to quantum systems and AI.

Let me briefly outline the key concepts and themes that will frequently appear in this book:

– Measurable time – metric, instrumentally defined;

– Immeasurable time – duration, meaning, subjective flow;

– Conversion point – threshold/platform where meaning becomes a potential signal of an event;

– Temporal crystallization condensate (TCC) – a working hypothesis of a local phase of meaning-ordering and neurophysiological coordination;

– Altered states of consciousness (ASCs) – practices and states granting access to the immeasurable;

– Timelessness – a state of falling out of habitual temporal supports;

– Mask therapy and integrative practices – clinical methods for safe entry into and exit from ASCs.

Where and how is this applicable? On the personal level – in therapeutic work: understanding temporal modes helps restore grounding, distinguish anxiety from insight, and carefully integrate experience. In social and collective life – in decision-making, strategic planning, crisis management: if foresight becomes a disciplined instrument, it may strengthen the resilience of communities; at the same time, it requires ethics and regulation. In science and philosophy – TCC offers a bridge between the phenomenology of meaning and formal models of time; in technology – ideas of temporal phases and informational coherence may provide new approaches to data analysis and interaction with AI.

I write directly and honestly: in this field there are many delicate boundaries. I pose questions, but I also preserve the sense of experience – that which cannot be reduced to graphs and formulas, but which manifests in lived reality. My request to you, reader: approach this material with curiosity and with criticism at once. Record your dreams and note your moments, apply the proposed protocols with care, and help us together to turn the spark of time into a clear instrument of understanding – not for dominion over the future, but for a more truthful and careful relationship with it.

S. A. Kravchenko

August 2025

Part I. Time in Human Experience

Chapter 1. Time in Myths, Religions, and Philosophy – from Plato to Heidegger

«Time is the moving image of eternity.»

– Plato

The history of humanity is, to a great extent, the history of our attempts to understand time. With the first calendars and sacrifices, people sought not merely to mark the rhythms of nature, but to rationalize and gain power over what slips away: the waking and falling asleep of the day, the change of seasons, that which leads all living things to their end. From these attempts were born myths, rituals, and philosophical teachings – different answers to the same question: What is time, and how should we live with it?

Myths and Religions: Personifications and Rhythms

In mythical imagination, time often takes a face. Among the ancient Greeks, two striking figures stand out. On one side is Chronos, the cruel ruler who devours his children, symbolizing relentless, destructive flow. On the other side is Kairos, the «moment,» the opportune chance, qualitative time of action: not what clocks measure, but what the soul feels. This pair – chronos and kairos – remains one of the key tools for distinguishing two modes of time, to which we constantly return in both practice and theory.

In Egyptian myths, time has a cyclical character: each morning the god Ra rises, overcoming darkness, and this ritual is an act of restoring cosmic order. In the Indian tradition, Kala (time) simultaneously destroys and creates; in the Bhagavad Gita, time appears as a force of destruction and transformation – devouring forms so that the new may be born. In my own observations, it is precisely this duality – destruction and creation – that often emerges in altered states of consciousness: the «past» dissolves, making space for the «new.»

For the monotheistic traditions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), time is given a linear meaning: the world has a beginning and a direction, history moves toward an end. In Christianity, this is expressed in the ideas of salvific history and resurrection; Augustine formulated the paradox of human experience of time with striking clarity: «What then is time? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain to one who asks, I know not.» His thought emphasizes that time is both an immediate datum of experience and a problem of language.

Buddhism, by contrast, emphasizes impermanence (anitya) and points to the illusory fixation of the «self» in time: liberation is connected to the experience of the present, with stepping outside the circle of samsara. In mystical traditions (both Eastern and Western), the image of the «timeless present» often appears – a state in which time as succession disappears, leaving only pure presence.

The Philosophical Tradition: From the Image of Eternity to Existence

Philosophers deepened and complicated these notions. Plato, in the Timaeus, called time the «moving image of eternity»: the ideal exists beyond time, while the sensible world is its reflection, subject to change. Aristotle gave the well-known definition: «time is the number of motion with respect to before and after,» embedding in the concept a relation to change and measure.

In the modern era, a debate arose about the status of time: Newton conceived it as an absolute background, a uniformly flowing «substance,» independent of the world; Leibniz regarded time as nothing more than relations among events, derivative of the interrelations of things. This dialogue – whether time has its own «reality» or arises from relations – remains relevant today.

Kant proposed a radical idea: time (like space) is a form of our sensibility, an a priori structure in which we construct experience. This was a shift: time is no longer merely a property of the world, but a condition of our cognition. In the 20th century, Husserl deepened the phenomenology of inner time, analyzing the stream of experience – the «stretching» of consciousness that cannot be reduced to mechanical divisions. Henri Bergson opposed «duration» (la durée) to mechanical time: for him, the present is not a sum of instants but a fused flow of experience.

Martin Heidegger, in Being and Time, shifted attention to the existential dimension: time is not the backdrop of existence but the very mode of human being. He showed that human Dasein is always «oriented toward the future,» yet permeated by being-toward-death; the notion of Sein-zum-Tode (being-toward-death) places time at the center of existence. For Heidegger, temporality is the horizon through which the meaning of being is disclosed.

Contemporary Questions: Thermodynamics, Arrows, and Relativity

Classical physics conceived of time as a parameter measured uniformly; the 20th century overturned this conception. Einstein’s relativity bound space and time into a single fabric – space-time – where local clocks tick differently depending on velocity and gravity. Here, there is no single «external» flow: time is local. Another crucial context is thermodynamics: the notion of the «arrow of time» (the direction from order toward entropy) explains why we remember the past but not the future. Boltzmann and his followers linked our historical sense of time’s direction to probability and chaos.

These scientific discoveries impart two key lessons to contemporary thought: (1) time can be local and relative, and (2) its direction is connected to information and thermodynamics. For us, this is crucial because it opens the possibility of a more complex model – where time not only «runs» but also «takes form» in particular conditions.

Conclusion and Transition to Practice

Through myths, religions, and philosophy runs a constant theme: time is not a passive backdrop but an active co-author of human life. From these traditions, we inherit a set of key images and concepts that I use throughout this book: chronos and kairos, duration and measure, linearity and cyclicity, «timeless presence» and existential temporality.

But I want to go further – not limit myself to the history of ideas. My clinical and research experience (altered states of consciousness, mask therapy, the Center for Anticipation, collaboration with the Levich Institute) shows that in human experience, time reveals other qualities – thresholds, points of conversion, moments when meaning and event enter into dialogue. In the following chapters, we will move from the history of ideas to a description of those phenomena of time that can be observed and tested in practice, and to a working hypothesis – the condensate of temporal crystallization (CTC) – as an attempt to connect the phenomenology of meaning with neurophysiology and theoretical physics.

Chapter 2. The Psychology of Time: Subjective and Objective Dimensions

«The specious present is the short duration we are immediately and incessantly sensible of.»

– William James

Time is one of the most reliable and at the same time the most elusive categories of human experience. It seems so self-evident that we rarely stop to describe it; but once we try, the simple picture dissolves into layers of theory, phenomenology, and personal experience. I always find it useful to keep two axes at hand – the objective (that which clocks and equations measure) and the subjective (that which a person experiences). Yet their separation is conditional; and the attempt to bring them together yields more than a mere sum.

Objective Time – Not the Simplest of Realities

Traditional classical physics treated time as a uniform background scale, identical for everyone – this was the Newtonian image. The 20th century introduced corrections: Einstein’s theory of relativity showed that the «sameness» of time is an illusion; the ticking of clocks depends on speed and gravity – time becomes local and relative. For practice, this carries a simple implication: there is no single universal «arrow,» but local rhythms and connections.

Beyond that lies quantum physics and cosmology – domains where the familiar «before and after» sometimes blur: the order of micro-events may not be strictly determined, and interpretations such as Everett’s «many-worlds» suggest the branching of realities. In theoretical physics, time may be multidimensional and part of a more complex structure than the one we are accustomed to. For us, as practitioners, this set of ideas matters not for its abstraction, but because it opens space for a model in which «time» can be locally reconfigured – what I later called the working hypothesis of the QTC (Quantum-Temporal Configuration).

(Behind this paragraph stands a serious body of scientific literature on relativity and modern hypotheses: Einstein on space-time and contemporary reviews on temporal structures.)

Subjective Time – The World of Experience

Subjective time is what we feel: the stretch of a minute in anxiety, the «flight» of an hour in the flow of creativity, the weight of memories that make the past heavy. This realm is closely tied to memory, attention, and emotion – but even more deeply, to states of consciousness. Altered states (meditation, hypnosis, autogenic training, sensory deprivation, psychedelic sessions) change not only the content of experience but also the very metric of time by which the brain organizes events. Research shows: experienced meditators regularly report a «slowing down» of time and an increase in the density of present experience. This is not just poetic description – empirical studies record stable changes in subjective time among practitioners of mindfulness. (Frontiers, PubMed)

Neuroscientific data provide us with working tools: there are brain networks associated with self-reflection and «background» activity – above all, the Default Mode Network (DMN). Immersion in a task or in a meditative state reduces DMN activity; in psychedelic states its organization is reconfigured. This correlates with the loss of ordinary self-reflection and with altered time perception. Such observations link the phenomenology of experience with concrete neurophysiological markers. (PNAS, annualreviews.org)

Psychedelics represent a separate case, now re-emerging into scientific discourse. Under the influence of psilocybin and similar substances, people often experience distortions in the familiar time scale: the sense of «stretching» or «dissolving» time, the loss of self-boundaries, the intensification of sensory connectivity. Neuroimaging shows that during such states the brain’s functional connectivity reorganizes, and its repertoire of dynamic states expands – providing physiological grounding for the experienced «blurring» of time. (PubMed, PMC)

Extreme Experiences: Near-Death States and the «Eternal Present»

Reports from people who have survived clinical death or deep near-death experiences often contain vivid temporal phenomena: «a whole life in an instant,» or the presence of countless images and events within one «now.» The large prospective AWARE study recorded a wide spectrum of cognitive experiences in cardiac arrest survivors; some reports pointed to the persistence or return of consciousness under conditions traditionally considered anatomically incompatible with awareness. These data do not offer an unequivocal interpretation of «timelessness,» but they do show that in extreme states subjective time can diverge radically from the linear model. (PubMed)

Ancestral Memory and Unconscious Layers of Experience

Our sense of the past is not limited to personal autobiography. Modern biological research points to inheritance mechanisms that shape descendants’ reactions: classical experiments on the transmission of specific fear responses across generations indicate epigenetic traces of experience. This does not prove «ancestral memory» in the mystical sense, but it provides a scientific context for understanding why in collective and archetypal images the past can feel more alive than mere recollection. For the psychologist, this means that representations of the past may emerge from deep intergenerational layers of the psyche, not only from individual memory. (PubMed, PMC)

Attention, Intentionality, and «Where the Present Resides»