Полная версия

In the Darkroom

A wall of glass with French doors overlooked the front terrace, but they, too, were dark, the thick drapes closed. “Someone could look in and want to steal my electronic equipment,” she said. She had a lot of it to steal. A wall-mounted cabinet system in the living room was filled, floor to ceiling, with monitors, receivers, amplifiers, speakers, woofers, CD, DVD, VHS, and Betamax players, a turntable, even a reel-to-reel tape machine. The last served to play her old opera recordings, the same ones my father used to blast every weekend in our suburban living room in Yorktown Heights. A half dozen cabinets contained a thousand or more operas on CDs, tapes, videos, and record albums.

Bookshelves lined the opposite wall. On one end were all my father’s old manuals on rock climbing, ice climbing, sailboat building, canoeing, woodworking, shortwave-radio and model-airplane construction. The My-Life-as-a-Man collection, I thought. Not that there was a corresponding woman’s section. Other shelves were populated with works devoted to all things Magyar: Hungarian Ancient History, Hungarian Fine Song, Hungarian Dog Breeds, and thick biographies of various Hungarian luminaries, including a two-volume set of memoirs by Countess Ilona Edelsheim Gyulai, the daughter-in-law of Admiral Miklós Horthy, the Regent who ruled Hungary during all but the final months of World War II.

Another section of books belonged to a genre that was as lifelong a preoccupation of my father’s as opera: fairy tales. Even as a girl, I understood that the puppet theater and the toy-train landscapes my father constructed were only ostensibly for his children. They gratified his craving for storybook fantasy. And the more extravagant the fantasy, the better. Likewise with opera. He hated a production that wasn’t lavishly costumed and staged. The two obsessions were, in fact, conjoined. One of my father’s most treasured childhood memories is of the night when his parents first took him to the Hungarian Royal Opera House. He was nine, and the opera was Hansel and Gretel.

“I wish I still had that book,” my father said, gazing over my shoulder at her impressive assortment of fairy tales. She was referring to a children’s anthology that the first of several nannies had read to Pista in his infancy. The nursemaid was German, and her mother tongue would become her young charge’s first language. “Leather binding, thick pages, gorgeous illustrations,” my father reminisced. “A gem. Whenever I go to a bookstore, I look for it.” Over the years she’d amassed many similar volumes, most featuring the tales of her most beloved storyteller, Hans Christian Andersen. She owned editions of his works in Danish, German, English, and Hungarian. (And could read them all. Like so many educated Hungarians, my father was a polyglot, fluent in five languages, plus Switzerdeutsch.) In 1972, when we took a family vacation to Denmark, my father made repeated pilgrimages to the Little Mermaid statue in Copenhagen’s harbor. I remember him standing for a long time by the seawall, pondering the sculpture of the sea nymph who cut out her tongue and split her tail to become human. I had studied him as he studied the statue, a girl in bronze on a surf-swept rock, her pain-racked limbs tucked beneath a nubile body, her mournful eyes turned longingly toward shore. My father had taken many pictures.

In idle moments on my first visit to Hegyvidék, and on the visits to come, I would take down from the shelf the English version of Hans Christian Andersen’s collected stories and leaf through its pages, repelled and riveted by the stories of mutilation and metamorphosis, dismemberment and resurrection: The vain dancing girl who has her feet amputated to reclaim her virtue. The one-legged tin soldier who falls in love with a ballerina paper cutout and, hurled into a stove, melts into a tiny metal heart. The lonely Jewish servant girl who dreams her whole life of being a Christian—and gets her wish at the resurrection. And most famously, the despised runt of the litter who grows into a regal cygnet. “I shall fly over to them, those royal birds!” says the Ugly Duckling. “It does not matter that one has been born in the hen yard as long as one has lain in a swan’s egg.” And I’d wonder: if the duckling only becomes a swan because he is born one, if the Little Mermaid cleaves her tail only to return to the sea, what kind of transformation were these stories promising?

On still more shelves on the living-room wall kitty-corner to the electronic equipment, stacks of photo albums contained snapshots from my father’s multiple trips to Odense, Andersen’s birthplace. “I took Ilonka there once,” my father said. “I think she was a little bored.” Flipping through them, I was startled to find a familiar townscape: the distinctive step-gabled roof of Vor Frue Kirke (the Church of Our Lady), a GASA produce shop (a Danish market cooperative), and the half-timbered inn of Den Gamle Kro (there’s an inn by that name a block from the Hans Christian Andersen Museum). Had my father reproduced the city of Odense in the train set he’d installed in our playroom? Later, when I inspected the two photos I still had of our childhood model railroad, I admired all the more the particularity of my father’s verisimilitude. The maroon snout of the toy locomotive bore the winged insignia and royal crown of the Danish State Railway.

Above the Odense photo albums, on two upper shelves, a set of figurines paraded: characters from The Wizard of Oz. My father had found them in a store in Manhattan, after my parents divorced and he’d moved back to the city. They were ornately accessorized. Dorothy sported ruby-red shoes and a woven basket, with a detachable Toto peeking out from under a red-and-white-checked cloth. The Tin Man wore a red heart on a chain and clutched a tiny oil can. The Scarecrow spewed tufts of straw, and the Lion displayed a silver-plated medal that read COURAGE. My father had strung wires to the head and limbs of the green-faced Wicked Witch of the West, turning her into a marionette. I paused before the dangling form and gave it a furtive push. The witch bobbled unsteadily on her broom.

My father pulled the drapes aside a few inches so we could slip through a glass door onto the terrace. I’d asked to see the view. The deck ran the length of the house and was lined with concrete flower boxes. Nothing was growing in them, except weeds. “You have to plant geraniums in May,” my father said, by way of explanation. In May, she had been lying in a hospital room in Thailand.

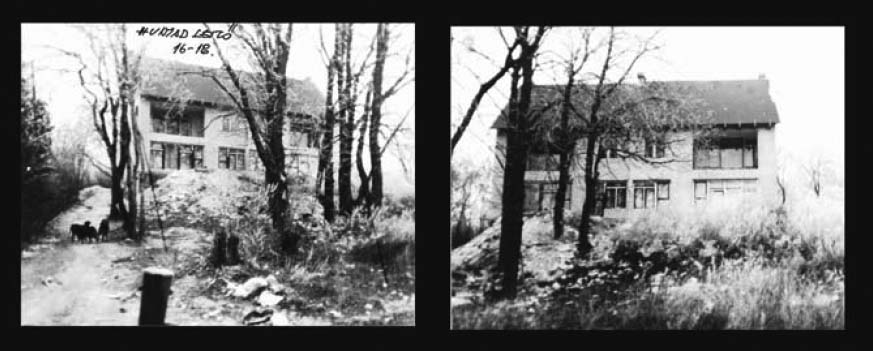

The lawn sloped steeply to the street. Down the center, a path of paving stones was shaded by huge and gnarled chestnut trees, an arboreal specter that put me in mind of Oz’s Haunted Forest (“I’d Turn Back If I Were You …”). Smashed shells and shriveled bits of nut meat littered the steps. From our aerie, you could see down a series of hills to a thickly wooded valley. To the right of the deck was a small orchard my father had planted when she first moved in. She enumerated the varieties: sour cherry, peach, apricot, apple, walnut. “Strange, though,” she said, “this year they bore no fruit.” Her horticultural inventory reminded her of the long-ago resident gardener who had tended the grounds of the Friedman villa in the Buda Hills, the villa where my father had spent every summer as a boy. “The gardener’s family lived in the cottage on our property,” she recalled.

She leaned over the far edge of the deck and pointed to a bungalow a half block below us, the only small structure on the street. “He lives there,” my father said.

“Who?”

“Bader.”

“Bader?”

“Baaader,” my father enunciated, correcting both my pronunciation and my failure to recognize the name. “Laci Baaader.” Laci, diminutive for László. “The gardener’s son.”

“You were playmates?”

“Haaardly. I was one of those.” Jews, she meant.

“That’s weird,” I said.

“What?”

“The coincidence. His living on your street now.”

My father didn’t think so. “He lives in his father’s house.” The gardener’s cottage that sat on my grandfather’s property. She pointed to one of the residential McMansions a stone’s throw from the Bader cottage. I could just see over the high concrete wall that moated it. It was, she said, the old Friedman villa. “There!”

The news rattled me. I had suspected that my father had purchased Buda Hills real estate as a way of recovering all that the Friedmans had lost. I hadn’t understood that my father had bought a house directly overlooking the scene of the crime.

“Waaall, it waaas there,” she amended. “They remodeled it, into that atrocity.” Nonetheless, some weeks after my father had arrived in Budapest on an exploratory visit in 1989, he’d tried to buy the atrocity. “It wasn’t for sale.” When a house nearby came on the market that fall, he’d paid the asking price at once, $131,250, in cash.

The house proved to be a disaster zone of shoddy and half-finished construction. My father summoned Laci Bader. “He took one look and he said, ‘This is no good!’” The roof was a sieve, the pipes broken, the insulation missing, the aluminum wiring a crazy-quilt death trap. “If you drilled into the wall, you’d get electrocuted.” It took most of a year, and tens of thousands of dollars more, to make the place habitable.

The house still needed significant maintenance, for which my father often enlisted Bader. “Now that I’m a lady, Bader fixes everything,” she said. “Men have to help me. I don’t lift a finger.” My father gave me a pointed look. “It’s one of the great advantages of being a woman,” she said. “You write about the disadvantages of being a woman, but I’ve only found advantages!” I wondered at the way my father’s new identity was in a dance with the old, her break from the past enlisted in an ongoing renegotiation with his history. She hadn’t regained the family property, but by her change in gender, she’d brought the Friedmans’ former gardener’s son back into service.

We went back inside, my father pulling the drapes shut again. She said she’d show me to my quarters. I followed her up the dark stairwell to the second floor, and into one of the three bedrooms.

“I sleep here sometimes, but I’m giving it to you because it’s got the view,” she said. She gestured toward the far wall of windows, which was shrouded in thick blackout liners covered by lace curtains. I inched the layers aside to see what lay behind them: closed casement windows that looked out over a concrete balcony, covered in dead leaves. A fraying hammock hung from rusted hooks. The walls were painted a pale pink and the room was blandly, impersonally furnished: a double bed in a white-painted wood frame, a white wooden wardrobe, a straight-back chair (an extra from the dining-room set downstairs), and an old television on a metal stand on wheels. A generic oil painting of a flower bouquet seemed to belong, like the rest of the decor, to a ’60s Howard Johnson’s.

“I had Ilonka sew this,” my father said, gesturing toward the matching fuschia duvet cover and pillowcases. “I built the bed frame. And the wardrobe.”

“You’re still doing carpentry?”

She said her workbench was in the basement. “Like in Yorktown.” She rapped her knuckles on the side of the wardrobe to demonstrate its solid craftsmanship. “You can hang your things in here,” she said.

I opened the wardrobe doors. My father followed my gaze into its shadowy innards and grimaced. Stuffed inside her hand-built armoire was a full armament of male clothing: three-piece business suits, double-breasted blazers, pin-striped shirts, khaki trousers, ski sweaters, rock-climbing knickers, plaid flannel jackets, hiking boots, oxfords, loafers, boat shoes, silk ties, wool socks, undershirts, BVDs, and the tuxedo my father wore to a family wedding.

“I need to get rid of all of this,” she said. “Someone will want these.”

“Who?”

“Talk to your husband.”

“He’s not my—” My boyfriend and I wouldn’t get married for a few more years. I could hear an old anxious hesitancy rising in my voice, which had suddenly lofted into helium registers. “He’s not your size,” I said, willing my voice to a lower pitch.

“These are quality clothes!” The hangers rattled as she slammed the closet door.

She left me to unpack. Ten minutes later, a summons from the adjoining bedroom. “Susaaan, come here!”

She was standing before a dressing table with a mirror framed in vanity lights. I recognized it: the makeup table for fashion models that used to sit in my father’s photo studio in Manhattan. She held an outfit in each hand, a yellow sundress with flounces and a navy-blue frock with a sailor-suit collar. “Which should I wear?”

I said I didn’t know. And thought, petulantly: change your clothes all you want, you’re still the same person.

“It’s hot out—I’ll wear the sundress.” She started peeling off her top. I backed toward the door.

“Where are you going?”

“To unpack.”

“Oh, come now,” she said, half in, half out of her blouse. “We’re all women here.”

She pulled the top over her head and gestured toward the closet. “Help me pick out the shoes to go with the dress.”

I stood in the threshold, one foot in, one foot out.

My father gave me a familiar half-grin. “Come closer, I won’t bite!”

5

The Person You Were Meant to Be

One evening in the early winter of 1976, an event occurred that would mark my childhood and forever after stand as a hinge moment in my life. The episode lay bare to my seventeen-year-old mind the threat undergirding the “traditional” arrangement of the sexes. Not just in principle and theory, but in brutal fact.

I was in my room, nodding over a book, when I was jolted awake by a loud crash. Someone was breaking into the house, and then pounding up the stairs with blood-curdling howls. It was my father, violating a restraining order. Six months earlier he had been barred from the premises. I heard wood splintering, a door giving way before a baseball bat. Then screams, a thudding noise. “Call the police,” my mother cried as she fled past my room. When I dialed 911, the dispatcher told me a squad car was on its way.

“Already?”

Yes, the dispatcher said. Some minutes earlier, an anonymous caller had reported “an intruder” at the same address.

The police arrived and an ambulance. The paramedics carried out on a stretcher the man my mother had recently begun seeing. He had been visiting that evening. His shirt was soaked in blood, and he had gone into shock. My father had attacked him with the baseball bat, then with the Swiss Army knife he always carried in his pocket. The stabbings, in the stomach, were multiple. It took the Peekskill Hospital’s ER doctors the better part of the night to stanch the bleeding. Getting the blood out of the house took longer. It was everywhere: on floors, walls, the landing, the stairs, the kitchen, the front hall. The living room looked like a scene out of Carrie, which, as it happened, had just come out that fall. When the house went on the market a year later, my mother and I were still trying to scrub stains from the carpet.

The night of his break-in, my father was treated for a superficial cut on the forehead and delivered to the county jail. He was released before morning. The next afternoon, he rang the bell of our next-door neighbor, wearing a slightly soiled head bandage, trussed up, as my mother put it later, “like the Spirit of ’76.” He was intent on purveying his side of the story: he’d entered the house to “save” his family from a trespasser. My father’s side prevailed, at least in the public forum. Two local newspapers (including one that my mother had begun writing for) ran items characterizing the night’s drama as a husband’s attempt to expel an intruder. The court reduced the charges to a misdemeanor and levied a small fine.

In the subsequent divorce trial, my father claimed to be the “wronged” husband. The judge acceded to my father’s request to pay no alimony and a mere $50 a week for the support of two children. My father also succeeded in having a paragraph inserted into the divorce decree that presented him as the injured party: by withdrawing her affections in the last months of their marriage, my mother had “endangered the defendant’s physical well being” and “caused the defendant to receive medical treatment and become ill.”

“I have had enough of impersonating a macho aggressive man that I have never been inside,” my father had written me. As I confronted, nearly three decades and nine time zones away, my father’s new self, it was hard for me to purge that image of the violent man from her new persona. Was I supposed to believe the one had been erased by the other, as handily as the divorce decree recast my father as the “endangered” victim? Could a new identity not only redeem but expunge its predecessor?

As I came of age in postwar America, the search for identity was assuming Holy Grail status, particularly for middle-class Americans seeking purchase in the new suburban sprawl. By the ’70s, “finding yourself” was the vaunted magic key, the portal to psychic well-being. In my own suburban town in Westchester County, it sometimes felt as if everyone I knew, myself included, was seeking guidance from books with titles like Quest for Identity, Self-Actualization, Be the Person You Were Meant to Be. Our teen center sponsored “encounter groups” where high schoolers could uncover their inner selfhood; local counseling services offered therapy sessions to “get in touch” with “the real you”; mothers in our neighborhood held consciousness-raising meetings to locate the “true” woman trapped inside the housedress. Liberating the repressed self was the ne plus ultra of the newly hatched women’s movement, as it was the clarion call for so many identity movements to follow. To fail in that quest was to suffer an “identity crisis,” the term of art minted by the reigning psychologist of the era, Erik Erikson.

But who is the person you “were meant to be”? Is who you are what you make of yourself, the self you fashion into being, or is it determined by your inheritance and all its fateful forces, genetic, familial, ethnic, religious, cultural, historical? In other words: is identity what you choose, or what you can’t escape?

If someone were to ask me to declare my identity, I’d say that, along with such ordinaries as nationality and profession, I am a woman and I am a Jew. Yet when I look deeper into either of these labels, I begin to doubt the grounds on which I can make the claim. I am a woman who has managed to bypass most of the rituals of traditional femininity. I didn’t have children. I didn’t yearn for maternity; my “biological clock” never alarmed me. I didn’t marry until well into middle age—and the wedding, to my boyfriend of twenty years, was a spur-of-the-moment affair at City Hall. I lack most domestic habits—I am an indifferent cook, rarely garden, never sew. I took up knitting for a while, though only after reading a feminist crafts book called Stitch ’n Bitch.

I am a Jew who knows next to nothing of Jewish law, ritual, prayers. At Passover seders, I mouth the first few words of the kiddush—with furtive peeks at the Haggadah’s phonetic rendition and only the dimmest sense of the meaning. I never attended Hebrew school; I wasn’t bat mitzvahed. We never belonged to the one synagogue in Yorktown Heights, which, anyway, was so loosey-goosey Reform it might as well have been Unitarian. I’m not, technically speaking, even Jewish. My mother is Jewish only on her father’s side, a lack of matrilineage that renders me gentile to all but the most liberal wing of the rabbinate.

So if my allegiance to these identities isn’t fused in observance and ritual, what is its source?

I am a Jew who grew up in a neighborhood populated with anti-Semites. I am a woman whose girlhood was steeped in the sexist stereotypes of early ’60s America. My sense of who I am, to the degree that I can locate its coordinates, seems to derive from a quality of resistance, a refusal to back down. If it’s threatened, I’ll assert it. My “identity” has quickened in those very places where it has been most under siege.

My neighborhood in Yorktown Heights was staunchly Catholic, mostly second-generation Irish and Italian, families who were one step out of the Bronx and eager to pull up the drawbridge against any other ethnicities or religions—in particular, blacks and Jews. In the mid-’60s, when a petition circulated to block a black family from buying a home on the street, my mother squared off against the petitioners. The family eventually bought the house; my mother remained the neighborhood pariah. Soon after we arrived, a boy down the street welcomed me by hurling rocks while yelling, “You’re a kike!” How he knew was a mystery: we’d shown no signs, and wouldn’t. My father made sure we aggressively celebrated Christmas and Easter and sent out holiday cards with Christian images (The Little Drummer Boy, Little Jesus in the Manger …). His eagerness to pass only reinforced my sense of grievance and, perversely, my commitment to an identity I barely understood. You could say that my Jewishness was bred by my father’s silence.

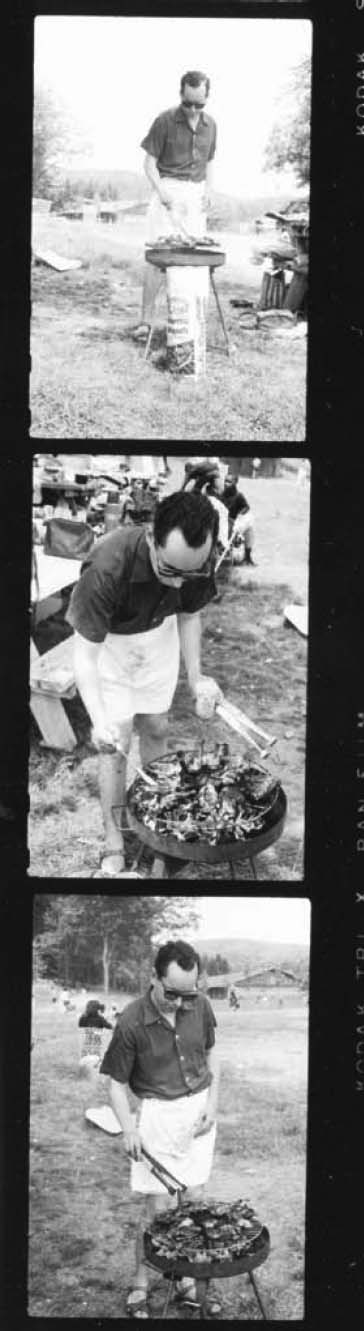

And my womanhood bred by my mother’s despair. When she gave up her job in the city (as an editor of a life-insurance periodical) and moved to the suburbs, my father awarded her the various accessories to go with her newly domesticated state: a dust mop, a housedress, hot rollers, a bouffant wig (with Styrofoam head stand, on which the hairpiece was left to languish), and a box of stationery printed with a new name that heralded the erasure of hers, “Mrs. Steven C. Faludi.” No doubt I learned some of my anti-nesting tendencies from my mother in this time. My father, for his part, was eager to present himself as a model of postwar American manhood, with wife and children as supporting cast, along with the convertible sports car (and before that, a Lincoln Continental), the saws and drills in the basement, the barbeque grill, the cigar boxes and pipe on the mantel, and the oversized armchair with a headrest in the living room that we all understood to be “his.” The chair was his throne, proof of his dominion and dominance over his quarter-acre crabgrass demesne. We were careful not to sit in it.

When I was in grade school, my father bought me a tabletop weaving loom. After a halfhearted effort that produced a couple of uneven fabric coasters and one miniature scarf, I took the loom off my desk and stashed it in the closet—to make room for my writing pads. Journalism was my calling from an early age. I perceived it, specifically, as something I did as a woman, an assertion of my female independence. I worked my way through stacks of library books on intrepid “girl reporters” and imagined myself in the role of various crusading female journalists, fictional and real, Harriet the Spy and His Girl Friday’s Hildy Johnson, Ida B. Wells and Ida Tarbell. In my schoolgirl fantasies, the incarnation of heroic womanhood was Nellie Bly exposing the horrors of Blackwell Island’s asylum for women, Martha Gellhorn infiltrating D-Day’s all-male press corps (and one-upping her war-correspondent husband, Ernest Hemingway). On the Little Red Riding Hood stage that my father had built, I turned the girl in the red cape into an investigative reporter uncovering the crimes of a wolf who was now the Big Bad Warmonger (it was the Nixon years). By fifth grade, I was championing my causes in my elementary school newspaper—for the Equal Rights Amendment and legal abortion—incurring the wrath of the John Birch Society, whose members denounced me before the school board as a propagator of loose morals and a “pinko Commie fascist.” The denunciations made me all the more a journalist, my sense of selfhood affirmed as that-in-my-makeup-that-someone-else-opposed. And all the more a defender of my gender. I asserted my fealty to women through my reportorial diatribes against the canon of womanly convention. I renounced the standards of femininity not to renounce my sex but to declare it. In short, I became a feminist.