Полная версия

Coach’s role in building athletes’ psychological resilience. Theoretical foundations and applied methods

Social factors are linked to the external environment in which an athlete develops. Support from the coach, family, team, and sports community plays a crucial role. Cooperation among team members, the proper coaching style, and a good microclimate are the stimuli for stress resilience and higher self-esteem. In contrast, too much pressure from the coach or assertive criticism can lead to heightened anxiety and emotional exhaustion. Social determinants also include the role of sports culture, club or federation custom, that influence an athlete’s preparedness to overcome a difficult situation and view stressful situations.

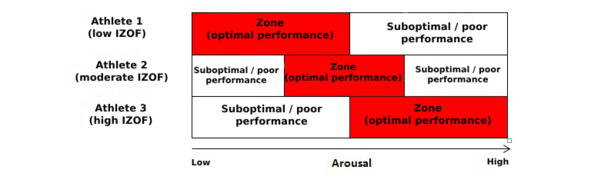

Modern research in the field of sports psychology also emphasizes the psychoregulation model proposed by Y. Hanin [11]. According to this model, each athlete has an Individual Zone of Optimal Functioning (IZOF), within which they demonstrate their best performance (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Individual zone of optimal functioning

This model suggests that each athlete has a unique level of arousal at which they perform at their best.

The horizontal axis represents the arousal level, ranging from low to high. The vertical axis categorizes athletes into three groups based on their IZOF:

• Athlete 1 (low IZOF) – athletes with a low optimal arousal level, who perform best at low activation levels. When their arousal level is high, their performance declines.

• Athlete 2 (moderate IZOF) – athletes with a moderate arousal level, who require a medium activation level to achieve optimal performance.

• Athlete 3 (high IZOF) – athletes for whom a high arousal level is optimal, while low activation leads to a decline in performance.

The red zones on the diagram represent the range of optimal functioning for each athlete. They indicate that the ideal arousal level for peak performance varies among athletes.

In this model, self-regulation of emotional states is the most significant feature. A player must be able to control the level of arousal so that he or she remains in their individual zone of best functioning. As illustration, low IZOF athletes would use relaxation and breathing capabilities to avoid being too highly aroused, and high IZOF athletes would respond positively to stimuli that arouse, like warm-up exercises using dynamics and methods increasing energy for readying the requisite level of competitiveness and motivation. This model highlights the importance of a personalized approach to managing emotional states and emphasizes individual differences in the optimal arousal level required to achieve peak athletic performance.

Swimming is an individual sport with particular demands on the psychophysiological status of an athlete [12]. As stated earlier, unlike game sports and team sports where players influence one another and modify their action under fluctuating conditions, swimming is a solo and cyclical activity. This influences the mode of psychological tension in competition and training and calls for a considerable amount of self-regulation, stress resistance, and cognitive regulation.

One of the most significant psychological determinants of success in a swimmer is the ability to concentrate and to manage attention. Swimming requires exact control of the technique of movement, coordination, and rhythmic organization of strokes, which calls for selective attention – the ability to focus on what is important and to disregard what is unimportant in a way that maintains concentration on tactical and technical aspects of performance. Since sensory isolation occurs in the water medium, where the swimmer has minimal exposure to audiovisual information, there has to be high internal concentration and body sensitivity.

The other important factor is emotional regulation and stress resilience. Like in any other sport, swimming is also associated with serious psychological stress, such as competitive anxiety, necessity to strictly adhere to time frames, and maximal physical effort. Nevertheless, unlike team sports athletes, who can adjust to extrinsic conditions and change their strategy in the process of competition, a swimmer’s performance is based on pre-programmed motor activity. This elevates the role of pre-competition psychological preparation. A sportsman ought to develop an optimal level of activation in advance, avoiding both over-arousal, as a result of which an individual may make mistakes at the start, and under-mobilization, when the reaction and movement force speed reduce.

The psychology of the process of training, which is characterized by intensive monotony and recurring movements, also exerts a strong influence on the psychological state of swimmers. It may cause intellectual and emotional fatigue, reduced motivation, and an increased level of psychological burnout. Therefore, the development of intrinsic motivation is highly significant, both for achievement of competition success and for an understanding of the importance of the process of training as such. The aquatic environment has certain circumstances where the sportspersons undergo bodily discomfort, hypoxia, and proprioceptive sensitivity change and hence need to manage their physiological and affective responses in the right manner.

The psychological aspect of competition preparation must be given a special emphasis since not only must the athlete get into best physical shape but also mentally practice how to deal with stress, rehearse successful performances, and reach the optimal confidence level. Compared to team sports, where strategy can be adjusted during the game, swimming contains a considerable psychological aspect, under which the players can practice in advance their order of operation and reduce uncertainty before the event begins.

Hence, psychological resilience in sport, including swimming, is a complex, multi-level process of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral adaptation strategies to stressors. Its emergence is conditioned by a cluster of biological, psychological, and social factors. Current scientific theories, such as cognitive-behavioral theory of stress resistance, theory of psychological adaptation, the theory of stress regulation, and the IZOF model of psychoregulation, explain mechanisms of stress resistance for formation in sportsmen, with special focus on cognitive appraisal of stress, self-strategies of stress coping, and emotional regulation.

Psychological resilience is especially important in swimming due to high sensory isolation, the necessity to precisely control technique and movement rhythm, and strong physical and psychological tension. One of the most important factors is emotional regulation, enabling sportsmen and women to achieve the optimal level of activation and stress acclimatization at competitions. Competition preparation includes learning mental techniques for anxiety regulation, effective visualization of performance, and self-confidence enhancers.

Psychological resilience development in swimmers requires an integrated training system that unites physiological and technical training with intensive cognitive self-regulation skills development. This helps athletes effectively cope with competitive pressure, retain concentration, and maintain high motivational levels throughout all stages of their sporting life.

1.2. Factors influencing an athlete’s psychological resilience

An athlete’s psychological resilience is a complex integrative phenomenon shaped by multiple factors, with personality traits, physiological characteristics, and the influence of the social environment playing a key role. This includes interactions with the coach, parents, and team. Psychological resilience results from the interaction between internal psychophysiological resources and external conditions established during an athlete’s training process.

Its development is determined not only by individual characteristics of the nervous system, temperament, and self-regulation strategies but also by the nature of social support, the level of a coach’s expectations, the type of feedback provided, and the emotional climate within the sports environment.

1.2.1. Physiological and personality characteristics

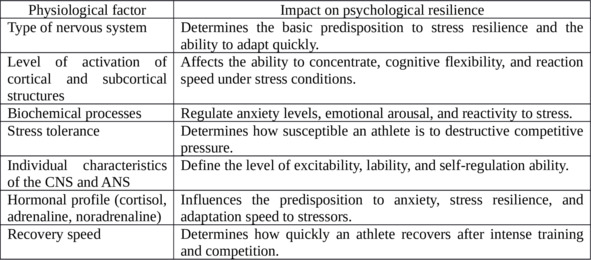

The development of psychological resilience largely depends on an athlete’s innate physiological traits. According to the biopsychological model proposed within the framework of neuropsychological research, key factors influencing stress resistance include the type of nervous system, the level of activation of cortical and subcortical structures, and biochemical processes responsible for regulating emotions and responses to stress [13].

Different athletes exhibit varying levels of tolerance to stress loads, which are determined by individual characteristics of the central and autonomic nervous systems, hormonal profile (levels of cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline), and the speed of recovery processes (table 1) [14].

Table 1. Physiological factors of stress resilience

Athletes have varying tolerance to stress loads, which is determined by individual characteristics of the central and autonomic nervous systems, hormonal profile (levels of cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline), and the speed of recovery processes.

These physiological factors also affect the athlete’s ability to maintain performance under continuous physical and emotional stress. Accurate profiling of these parameters facilitates enhanced individualization of training and adaptation tracking. Emotional regulation mechanisms and cognitive control are also critical in maintaining stability under competition.

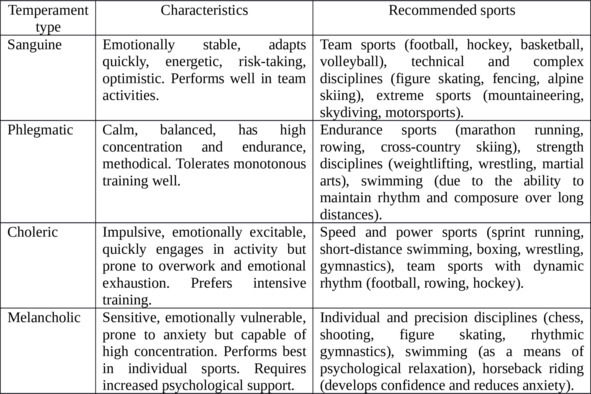

Different sports impose specific demands on an athlete’s psychophysiological characteristics. Therefore, temperament largely determines predisposition to certain disciplines, influencing concentration ability, stress resilience, and motivation levels (table 2) [15].

Table 2. The influence of temperament on predisposition to sports

Thus, temperament plays a significant role in the adaptation of an athlete to sports competition, stress resistance, concentration capacity, and performance level in severe conditions. Choosing a sport corresponding to the psychological characteristics of an individual optimizes the process of training, reduces psycho-emotional stress, and enhances athletic performance.

Additionally, the degree of anxiety, emotional lability, and cognitive capabilities also matters. Increased anxiety exerts a detrimental effect on the athlete’s concentration potential, stress-based decision-making ability, and self-regulation during competitions. Good cognitive abilities in reappraisal of stress-inducing situations, self-regulation, and awareness of emotional response, in contrast, are sound indicators of adaptation in sport.

According to a study [16] conducted among 273 athletes (aged 12 to 34, selected through random sampling), a significant relationship was identified between anxiety, self-confidence, and concentration. The analysis revealed four key factors influencing stress resilience: cognitive anxiety (24.83% of total variance), somatic anxiety (11.86%), self-confidence (15.49%), and concentration (11.05%). It was found that athletes with high levels of cognitive anxiety more frequently exhibited decreased concentration and struggled more with stress. At the same time, self-confidence served as a protective factor: athletes with higher self-confidence levels had significantly lower anxiety and better concentration.

Based on the Mann – Whitney U test, a significant gender difference was found in cognitive indicators, self-confidence, and concentration. Women experienced higher cognitive anxiety (11.67 ± 3.97 vs. 9.26 ± 3.23 in men), while men demonstrated higher self-confidence (19.54 ± 3.08 vs. 17.47 ± 3.74 in women).

The study verified that the well-documented cognitive reappraisal skill of stressful events, self-regulation, and familiarity with emotional responses are key to the successful adaptation of athletes. Athletes who employed cognitive self-regulation strategies on a regular basis (reframing, attention control, success visualization) possessed 23% higher rates of concentration during competitions and 17% reduced anxiety levels compared to the control group. Particular stress management instruction and self-esteem skills contribute to enhance enhanced sporting performance and resilience to stress in pressure situations.

Physiological characteristics, including some level of physical fitness, rate of recovery, and hardness, also have an important role to play in psychological resilience in sport. Studies affirm that fitter athletes exhibit more stable emotion regulation, which relates to the capacity of the body to adapt against stress and smaller biochemical reaction to stress.

A review of scientific studies [17] confirmed that regular physical activity reduces cortisol levels by an average of 0,37 standard deviations. This influence indicates a moderate but statistically significant decrease of the stress hormone, which results in reduced psycho-emotional tension. The meta-analysis included 10 RCT with a sample of 756 individuals, predominantly women (90%). Various methods of cortisol measurement were used in the studies (saliva, blood), but regardless of the method, intervention groups showed a significant decrease in hormone levels in comparison with control groups.

Thus, psychological resilience of a sportsman is largely characterized by his or her physiological characteristics, degree of physical preparedness, and endogenous nervous system characteristics forming a foundation for adaptive self-regulation mechanisms during severe physical and mental stress. Besides personal biological characteristics, social conditions engage in stress resistance, e.g., communication with coaches, team members, and parents.

1.2.2. The influence of the social environment on an athlete’s psychological resilience

A sportsperson’s psychological resilience is not just determined by individual and physiological factors but also through social encounters with the environment they are exposed to during training and competition. Among the social determinants of stress resilience, family support and the sporting environment play a very crucial role.

Family support is a key to the formation of motivation, self-confidence, and coping with problems [18]. Parents affect the perception of stressful experience by an athlete, his/her attitude towards wins and losses, level of self-confidence, and resistance to failure.

In sports psychology, three main models of parental influence on the development of stress resilience in young athletes have been identified (fig. 6).

Figure 6. Main models of parental influence

The emotionally detached model is one in which parents are least involved in the sporting life of a child. Different from the controlling or supportive styles, where there is a parental active involvement in the sporting life of a child through organizational or emotional support, this model is one in which parents either completely avoid the training process or do not care about the failures and achievements of the young athlete. Thereby, the kid develops some of the psychological issues that hinder their motivation, self-esteem, and ability to deal with stressful events [19].

Distantness has a number of its dire outcomes involving loss of internal motivation and external motivation. Non-reinforcement or lack of validation by the parents towards the efforts of the child denies a long-term belief that sports are worthwhile to be engaged in. Validation from elsewhere being absent, the child’s practice interest may decrease as they no longer feel their labor to be recognized and cherished by others. This has a specific impact on intrinsic motivation, which is of vital significance in sports as it decides the athlete’s capacity to continue training and overcome obstacles even in the absence of instant success.

Decreasing self-confidence is another key feature. One of the greatest influences on positive self and belief in ability is the support of parents. If parents are not interested in such sporting achievement by their child, then the child will begin questioning the importance of such achievement, therefore doing away with self-confidence and lower confidence in their capability. Lack of sufficient positive reinforcement compromises the athlete’s belief of competence, something which is very vital during pressurizing situations like competition where there needs to be high self-efficacy.

Additionally, kids raised in a culture of remote parental involvement are prone to struggle with overcoming stressful experiences. Unlike kids whose parents take an active role in helping them learn coping strategies, these athletes must look after themselves when they encounter anxiety, mood swings, and disappointment. The absence of positive conversations about failures and support during difficult moments reduces a child’s resilience in the face of psychological stress.

Another negative consequence is the feeling of emotional isolation and a decrease in attachment levels. Parents who have limited interest in their child’s sporting career can create a sense of emotional distance, which can lead to lower overall emotional resilience and self-regulation capacity. Research in sports psychology indicates that children who receive little emotional support from parents are more likely to experience frustration, anxiety, and feeling insignificant, which can influence both sporting performance and overall psychological well-being [20, 21].

Thus, a model of remote parental involvement in sport can bring about several negative consequences, including reduced motivation, self-esteem, and resistance to stress. To prevent these consequences, parents, even if they are not interested in their child’s sport, should provide at least minimal support, recognize achievements, help them overcome failures, and encourage independence in attaining their sporting objectives.

The controlling model is characterized by parental over-control in which the parents will seek to manage their child’s participation in sport in its entire form, becoming the primary organizers of training and competition. Parents employing this model are typically over-concerned with the end result of competition, are single-mindedly outcome-oriented, achievement-focussed, and place high expectations and strict success criteria. This parenting style has various psychological consequences, all of which reduce the stress resilience and well-being of young athletes.

One of the most pronounced effects of this overprotective model is increased pre-competition anxiety. Children under constant parental pressure experience significant worry before competitions, perceiving them not as an opportunity to demonstrate their abilities but as a test where failure could lead to disappointment from their parents. This results in cognitive overload, the development of irrational beliefs (“If I lose, I will no longer be supported”, “My mistakes are unacceptable”), and reduced self-confidence.

Furthermore, overprotection lowers an athlete’s level of independence and self-regulation. Parents who wish to direct every action of their child deprive them of decision-making, and as a result, they become less capable of dealing with stressful situations. In competitive situations where adaptability is a requirement, quick response, and coping with ambiguity, these players falter since they are accustomed to relying on external direction and instruction.

Another negative consequence of overprotection is the development of dependence on external evaluation. An athlete raised in an environment of constant control and high expectations begins to perceive success not as a personal achievement but as a way to fulfill their parents’ ambitions. As a result, their motivation becomes primarily external (extrinsic motivation) – they strive not for self-realization but for praise and approval. In cases of failure, such children experience deep disappointment, guilt, and a loss of motivation for further training.

Thus, the overprotective parental style in sport generates psychological barriers, not allowing for the building of stress resilience. To minimize its negative influence, it is required to redistribute the responsibility for success and failure, promote the development of intrinsically motivated behavior, and build self-confidence in athletes that is independent of external evaluation.

Supporting parental model assumes an active participation of parents in the sport activity of a child in the form of genuine interest in their successes, moral support, and reinforcement of a healthy relationship with training and competition. They do not promote outcomes but create an environment for success and failure so that the child can realize them as a process of development and living. They favor initiative, autonomy, and efforts towards self-actualization, thereby promoting intrinsic motivation, which is of central concern in long-term sport participation maintenance.

In this approach, the child is praised in failure and develop confidence through positive reinforcement of progress and effort. Interestingly, parents do not necessarily praise success but instead praise the effort that has been invested in achieving results, thus eradicating fear of failure. This approach allows the athlete to build psychological toughness, their stress tolerance is increased, and competition-induced anxiety is reduced. Besides, the supportive parenting model creates a warm emotional atmosphere, enriches the feeling of security and trust, which is crucial for a child’s self-confidence development and the ability to self-regulate.

Interaction in this model also contributes to the development of positive coping strategies for stress. Athletes who have parental support more successfully utilize cognitive and behavioral mechanisms for overcoming setbacks, adjust to high workloads with greater ease, and maintain their emotional stability even under the circumstances of high competitiveness. Parents adhering to this style not only serve as a source of emotional stability but also as a guiding force for the development of a mature and conscious attitude towards sports.

The most effective parenting style in building psychological resilience is the supportive style, whereby the parents help the athlete cope with adversity but allow the athlete decision-making autonomy and emotional independence from others.

The sports environment, including the team, training partners, and peers, has a significant impact on emotional regulation, motivation levels, and an athlete’s ability to adapt to stressful situations [22]. In sports groups, a specific social atmosphere is formed, which can either contribute to the development of stress resilience or, conversely, increase levels of anxiety and tension (fig. 7).

Figure 7. The influence of the team on an athlete’s psychological resilience

Social support, in the form of perceived togetherness in the team, harmonious relations with the team members, and support from peers, is most critical to reduce the levels of anxiety and hardiness formation. In a team, after a sportsperson is emotionally supported and viewed as being trusted by others, supportive environment is built to develop self-confidence, effort drive to surmount the failures, and positive attitude towards failure. Positive group climate and mutual understanding lower competitive tension and lower negative response to stressful conditions.

The competitive environment, in turn, can either promote an athlete’s psychological growth or lead to emotional exhaustion, depending on the level of competition and the nature of interpersonal interactions. A positive competitive atmosphere provokes athletes to self-develop, achieve self-regulation skills, and be goal-oriented. However, exaggerated intensification of competitive pressure, generating conflicts, interpersonal tension, and constant comparison with others, can reduce self-confidence, induce anxiety, and hinder successful recovery after failure. To provide the optimal level of motivation, it is necessary that teams adopt clear principles of competitive interaction, eliminating aggressive competition and fostering respect and mutual support for athletes.