Полная версия

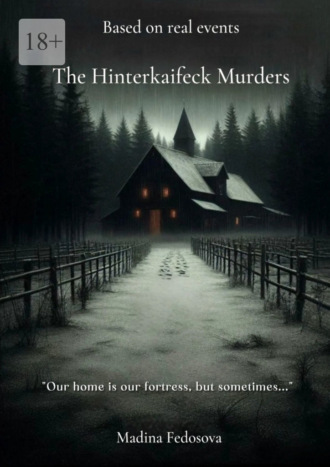

The Hinterkaifeck Murders

The isolation of the Gruber family became increasingly palpable, and the shame – increasingly unbearable.

The Grubers, already unsociable, became even more withdrawn. The Hinterkaifeck farm turned into their personal world, where they were left to their own devices. Trips to the village for necessities turned into an unpleasant duty, and communication with neighbors – into a formality.

In 1915, after several months of agonizing preliminary investigation, Weidhofen froze in anticipation. In the courtroom, reeking of dampness and mothballs from old uniforms, a trial began that could overturn the foundations of the entire district: the trial of Andreas Gruber and Victoria Gabriel.

Only fragmentary information about that trial has survived. The minutes of the court session have disappeared without a trace, leaving historians and biographers only room for speculation. It is unknown who exactly initiated the case, who gave the first testimony, who dared to break the long-standing silence of Hinterkaifeck.

In court, everything was turned upside down. Victoria, who had expected sympathy and help, appeared before the court as an accomplice in the crime. She was accused of not resisting her father’s will, of remaining silent, covering up his sin. Andreas Gruber, on the contrary, held himself arrogantly and confidently, denying all the charges. What they actually said, what arguments they presented, remained a mystery.

One cannot rule out that there was no publicity at all, but only a piece of evidence. The prosecution, representing the state, may have used it to initiate legal proceedings. After all, in criminal proceedings, the victims only supplement the lawsuit, the main role is played by the prosecution, represented by the state.

The court delivered its verdict: Victoria Gabriel was found guilty and sentenced to one month in prison. Andreas Gruber received a more severe punishment – one year in prison. A sentence that caused surprise and whispers in the village. Was this justice or just a semblance of justice? After all, the perpetrator of a brutal crime got away with such a lenient punishment.

Who could have reported the Grubers’ sins? Suspicion fell on Maximilian Altmann, Victoria’s half-brother. This fact added dark colors to an already dark picture. Martin, as some believed, may have been a witness to this connection between his sister and stepfather. Perhaps he had kept this terrible secret to himself for many years, fueled by his own resentment. After all, after his father’s death, Martin received only a paltry 100 marks of inheritance, while his sister Cäzilia Starringer became richer by as much as 700 marks. Could envy and a thirst for justice have pushed him to betrayal?

Martin was the only male heir, and who knows what thoughts were swirling in his head. Perhaps he considered himself more worthy of managing the farm than his half-sister, and this trial was his way of regaining his lost position. It is quite likely that revenge became his only way to drown out years of pain and humiliation.

However, it remained unclear how Martin could calmly live under the same roof with people he had accused of such a terrible crime. Victoria, the powerful mistress of the farm, would surely not tolerate the presence of a traitor. Unless, of course, Martin was cunning enough to remain in the shadows, acting anonymously, leaking information to the prosecutor’s office, while remaining unnoticed in Hinterkaifeck. The true motives of Maximilian Altmann will forever remain a mystery, buried beneath a layer of time and gossip.

According to another version, Victoria Bauer revealed the secret. There were rumors that it was to her, her namesake, that Victoria Gabriel confided in a fit of despair, pouring out her soul and telling about the dark secret that tormented her. Perhaps Bauer, driven by moral principles or sympathy for her friend, could not keep this terrible secret. Maybe she tried to persuade Victoria Gabriel to turn to the authorities, and when she refused, she took a desperate step and sent an anonymous denunciation. Perhaps she hoped to save Victoria from her father’s power, even against her will. What exactly prompted Victoria Bauer to such an act – sympathy, a sense of duty, or something else – will forever remain a mystery.

Yet another version linked the trial to the Gabriel family. Many drew attention to the fact that the case of blood revenge was initiated shortly before the birth of Cäzilia, Victoria’s daughter. This suggested that the birth of the child and the subsequent accusation were somehow connected. Klaus Briel Sr., the father of Klaus who died in the war, may have long suspected an unhealthy relationship between Victoria and her father.

It is possible that the Gabriel family doubted Cäzilia’s paternity. Any doubt about the child’s origin could serve as a motive for revenge.

Perhaps it was Klaus Briel Sr. who anonymously informed the authorities about the crime, wanting to avenge his son’s violated honor and protect the purity of his blood.

Moreover, at that time, a dispute arose between the Gabriel and Gruber families over the inheritance of the deceased Klaus Jr., which could have prompted the old man to take decisive action. Perhaps this was a cunning move in the struggle for family lands, a carefully planned revenge, disguised as concern for justice.

Some whispered about the neighboring workers who were working on the reconstruction of Hinterkaifeck in those years. Josef Steinerr, in his later testimony, confirmed that between 1908 and 1909 the farm was bustling with activity, and local residents were helping the Grubers.

In his testimony, he stated:

«I was well acquainted with all the residents of Hinterkaifeck,» he claimed, «and even helped them harvest, including during the war when Klaus Briel died in France.» He knew everyone except the mysterious strangers who never appeared in the Hinterkaifeck yard.

There were rumors that old Gruber was maintaining «incest’ with his widowed daughter, and Steinerr even claimed to have seen gendarmes arrest him for it in the meadow – a case shrouded in the fog of time and casting doubt on the veracity of the memories.

Steiner didn’t know how Victoria behaved with men after her husband’s death, but he remembered that once she was «in blessed circumstances’, and everyone in the village gossiped that the child’s father was her own father. And this concerned not Cäzilia, who had already grown up on the estate, but that boy, who died as a result of the murder… but we will return to this later. Steiner even remembered the autumn day in 1919 when he was helping to thresh grain on the farm. Then the old man Gruber dropped a strange phrase: «Oh, May Bubben («my friends’ in the local dialect’), I hardly went to sleep this night… last night a young woman gave birth… Yes, from my point of view, it would be whoever wanted it, including Bauersepp because of me!»»

I apologize again for the previous errors. I’ve tried my best to provide you with an accurate translation of this section.

Under «Bauersepp’, as everyone understood, Gruber meant himself, indirectly admitting his involvement in his daughter’s pregnancy and expressing dissatisfaction with the child’s father. Who this father was remained only to be guessed. But one thing was clear: the secrets of Hinterkaifeck, like a thick fog, shrouded every event, distorting and refracting the truth.

Perhaps, during these works, amidst the noise of saws and axes, one of them managed to see or hear what was hidden behind the closed doors of the house. They watched the lives of the inhabitants of Hinterkaifeck, noticed oddities in the relationship between father and daughter, and these observations, like seeds, long sprouted in their minds.

But why then did they remain silent for so many years? If they really witnessed a crime, why did the anonymous denunciation appear only years later? Perhaps fear of Andreas Gruber, a powerful and cruel man, forced them to remain silent. Or maybe they were just waiting for the right moment, until the burden of guilt and silence became unbearable.

But, of course, one could not exclude the possibility that all these versions were only speculation and fantasies, born of popular rumor. Perhaps none of the people listed had anything to do with this story. Perhaps the anonymous denunciation was the work of a completely different person, whose motives and name will forever remain a secret. And, perhaps, all these assumptions and conjectures are just an attempt to fill the void created by the absence of truth.

The Neuburg an der Donau Prosecutor’s Office filed charges as part of case number Str.P.Reg. 105/15, and on May 28, 1915, the court delivered its verdict. Andreas Gruber and Victoria Gabriel were found guilty of a crime against morality, better known as «shame on blood’. The court considered proven the fact of incestuous relations that took place between 1907 and 1910.

Article 173 of the German Criminal Code, which was in force in those years (from January 1, 1872, to October 1, 1953), regulated the punishment for incest, that is, sexual relations between close relatives. It was under this article that Gruber and Gabriel were most likely convicted. The article stated:

(1) Sexual intercourse between relatives in the ascending and descending line (for example, between father and daughter, grandfather and granddaughter) shall be punished for the first case by imprisonment for a term of up to five years, for the second case by imprisonment for a term of up to two years.

(2) Sexual intercourse between relatives in the collateral line (brothers and sisters) shall be punished by imprisonment for a term of up to two years.

(3) In addition to imprisonment, the court could deprive the convicts of civil rights.

(4) Minor (under eighteen years of age) relatives were exempt from punishment.

But why was incest punishable by law? The prohibition of incest has deep historical roots and is associated with a number of factors. First of all, it is concern for the health of offspring. Genetically close relatives, entering into sexual relations, increase the likelihood of transmission of recessive (hidden) genes responsible for hereditary diseases. As a result, children may be born with physical deformities, mental retardation, and other health problems.

In addition, the prohibition of incest contributed to the maintenance of social stability. It regulated marital relations, created clear boundaries between families, and prevented conflicts over the distribution of resources and power. Incest, by destroying these boundaries, could lead to chaos and the disintegration of society.

In a religious context, incest was often seen as a desecration, a violation of divine commandments and, as a result, a sin. In Christianity, for example, the prohibition of incest was part of the moral code and served to strengthen family values.

The trial of Gruber and Gabriel was a stark reminder of the moral norms that prevailed in German society at that time. It reflected the struggle to preserve these norms, to protect the family and the health of future generations. But, as the history of Hinterkaifeck showed, these norms could not always withstand the dark secrets hidden in the depths of the human soul.

Andreas Gruber, having served a year in prison for incest, returned to Hinterkaifeck. This was a slap in the face to the public, a mockery of law and morality. He seemed to be saying to everyone: «You can’t do anything to me.» And indeed, what could ordinary peasants do against a man who, it seemed, feared neither God nor the devil?

Having returned, Gruber continued to live with Victoria as if nothing had happened. He seemed to be declaring his power over her, over the family, and over all of Hinterkaifeck. It was a demonstration of impunity that aroused only whispers of horror and disgust in the district.

How could Victoria live with a man who had abused her, with a father who should have been despised? How could the neighbors tolerate the presence of this monster? The answer lay in the atmosphere of fear and silence that reigned in Hinterkaifeck.

Andreas Gruber’s return from prison brought with it not only scandal, but also, it seemed, an iron grip that bound Victoria in its vise. His ban on remarriage became another link in the chain of violence and subjugation. After Klaus Briel’s death, Victoria theoretically had the opportunity to start a new life, find herself a husband, and break free from her father’s oppression. But Gruber, having returned, as if proclaimed: «You belong to me.»

This prohibition may not have been legally formalized, but it had enormous power, based on fear, dependence, and moral pressure. It deprived Victoria of freedom of choice, condemning her to loneliness and complete dependence on her father’s will.

Victoria was trapped: public condemnation, economic dependence, and fear of Gruber deprived her of the slightest opportunity to resist. She was attached to Hinterkaifeck, to her father, to her past, and this attachment, as it turned out, led to imminent death.

Chapter 8Neighborly Connection1910—1913Just five hundred meters from Hinterkaifeck, from its grief-soaked fields and gloomy forests, stood the house of Kurt Wagner. It seems that these five hundred meters, separating the solid Wagner yard and the Gruber estate, defined the difference between worlds: a world of prosperity and well-being, where life was in full swing, and a world of fear and despair, where it slowly faded away. In one house, laughter of children, the ringing of a blacksmith’s hammer, and the steady hum of a working mill were heard. In the other – only the creaking of floorboards, muffled sighs, and a silent anticipation of something terrible.

But these five hundred meters were deceptive. They could not isolate Kurt Wagner from what was happening in Hinterkaifeck. As the village elder, he was aware of all the events, knew about the dark rumors surrounding the Gruber family, about the incest, about Andreas’s strange behavior. He tried to do something, turned to the authorities, but faced indifference and a reluctance to interfere in other people’s affairs.

Kurt Wagner was indeed a prominent figure in the district, and not only because of his solid house, towering just five hundred meters from the gloomy Gruber estate. He was one of those people who would now be called «influential’. His farm prospered, the land yielded a good harvest, and the solid house was a clear testament to wealth and a solid position in society. Wagner did not just live, he led, set the tone.

The respect and authority he enjoyed among his neighbors was not just an empty phrase. He was the village elder, which in those days meant much more than just an administrative position. The elder was a mediator between the peasants and the authorities, resolved disputes, organized joint works, and maintained order. Kurt was a kind of «gray cardinal’, a person to whom people turned for advice and help.

He was respected for his judgment and fairness. Kurt knew how to listen and hear, weigh all the «pros’ and «cons’, and make decisions that seemed fair to most. Of course, he was not a saint; he had his own interests and shortcomings. But on the whole, he was a man who was trusted and whose opinion carried weight.

Wagner’s influence extended not only to the village, but also to the surrounding lands. He was a major landowner, and the fate of many peasants depended on his decisions. He could give work, he could help in a difficult moment, but he could also refuse, condemning a family to starvation.

In the history of Hinterkaifeck, Kurt Wagner played an important role. He was one of those who tried to figure out what had happened, who sought the truth and tried to punish the guilty. His influence and connections helped in the investigation, although, as we know, the case was never fully solved. He, like many other residents of Hinterkaifeck, remained forever with the burden of this tragedy, with a sense of injustice and powerlessness.

1918 brought grief to the Wagner household. The death of Kurt’s first wife was an unexpected blow, like a bolt from the blue. The family was shocked, the household was orphaned, and Kurt himself seemed to have lost his footing in life. The district sympathized, neighbors came to support him, brought food, and offered help around the house. Grief united people, and it seemed that Wagner was drowning in sympathy and support.

But Kurt’s mourning turned out to be suspiciously short. Just fourteen days after the funeral, rumors began to spread through the village, at first quiet and uncertain, then louder and more persistent: Kurt Wagner had been seen in close relationship with Victoria Gruber.

These rumors caused a real stir among the neighbors. How could this be possible? He hadn’t even finished mourning his wife, and he was already seen with Victoria, around whom there were so many unkind rumors…

Wagner seemed to pay no attention to the gossip. He continued to visit Victoria, helped her around the house, and there were even rumors that he was going to marry her. This was madness. If he was really going to do this, then it meant that he had either lost his mind from grief or was pursuing some hidden goals of his own.

Soon Victoria became pregnant. Like sparks from a fire, rumors spread throughout the district, fueled by curiosity and whispers. Who is the child’s father? This question caused lively discussions among those who followed the lives of both families.

Andreas Gruber bristled, vehemently denying his involvement. He swore that Kurt was the father, trying to shift the burden of shame and suspicion onto his neighbor’s shoulders. Perhaps there was some truth in his words, but in Hinterkaifeck it was more difficult to find the truth than a needle in a haystack.

However, strangely enough, Kurt himself did not believe in fatherhood. His words conveyed not so much joy at future fatherhood, but rather doubt, distrust, and even disgust. Knowing firsthand about the unhealthy atmosphere that reigned in the Gruber household, he did not want to take responsibility for a child who may have been conceived as a result of incest.

Wagner’s doubts only added fuel to the fire of rumors and suspicions. People whispered behind Victoria’s back, cast sidelong glances at Kurt, and discussed the dark secrets of Hinterkaifeck with renewed vigor. Victoria’s pregnancy was not a joyous event, but rather a new twist in the drama, foreshadowing even greater tragedy.

The mystery of Victoria’s child’s paternity remained unsolved. Kurt Wagner publicly refused to acknowledge his fatherhood, Andreas Gruber denied his involvement, and Victoria, unfortunately, left no evidence capable of shedding light on this issue.

Despite the lack of reliable information, many residents of Hinterkaifeck believed that Andreas Gruber was the father of the child. This point of view, of course, was formed against the background of long-standing disturbing rumors about unhealthy relationships within the Gruber family. In addition, it cannot be denied that public opinion about the Gruber family at that time was far from the most benevolent.

Kurt Wagner, despite his doubts, still decided on an act that shocked Hinterkaifeck no less than the news of Victoria’s pregnancy.

What motivated him? Public opinion, which was putting tremendous pressure on him? Sincere sympathy for the fate of an unhappy woman? Or a desire to strengthen his influence and position in the district by becoming related to the family, albeit such a controversial one? Perhaps all these factors played a role.

Whatever the case, Kurt Wagner went to Andreas Gruber with a request to give him his daughter Victoria as his wife. This was an unprecedented step, which caused surprise and gossip. Many did not understand why a respected man would connect his life with a woman who had tainted herself with scandal and notoriety.

Marriage to Kurt could certainly be a salvation for Victoria. It could rid her of the stigma of incest, provide her with a stable future, and restore respect in the eyes of society. Wagner was a wealthy and influential man, and his support could change Victoria’s life for the better. But was it a sincere desire to help an unhappy woman or a calculated move aimed at achieving his own goals? Only Kurt Wagner himself knew about this.

But Andreas Gruber, succumbing, perhaps, to his deepest complexes and, as we now know, under the influence of certain circumstances that, unfortunately, have forever remained hidden from us, gave Kurt Wagner a sharp refusal.

«I can caress my daughter myself,» he said cynically, not shy about anyone or anything.

Unfortunately, this refusal deprived Victoria of the opportunity to somehow change her life, to get at least a glimmer of hope for deliverance from the oppressive dependence in which she found herself. In a fit of feelings that are now difficult for us to understand, Andreas locked his daughter in the closet so that she could not even look at the person who, perhaps, could have become a support for her.

He probably understood that Victoria’s marriage to Kurt could lead to a loss of control over what was most important to him. The documents show that it was Victoria who was to inherit Hinterkaifeck, and therefore her future child would also have rights to the property. If Josef was recognized as Kurt’s son, then the latter, as husband and father, could also claim ownership of the land. Andreas, apparently, could not allow this to happen.

1919, winter gripped Hinterkaifeck in a deathly hold, bringing with it not only cold, but also the birth of Josef – Victoria’s son. There was irony in this name, Josef. After all, Josef in Hebrew means «God will increase’. But in Hinterkaifeck, only grief and secrets multiplied. The question of paternity haunted both Victoria and Kurt.

1915

Doubts tormented Kurt, preventing him from finding peace of mind. Josef… was he really his son or just evidence of a shameful secret, an echo of the incest that filled the village? He was afraid of becoming a pawn in someone else’s game, of paying for sins he had nothing to do with.

One day, on a gray autumn day, when rain was monotonously tapping on the glass, Kurt made a decision, as if shedding a heavy burden. Unable to endure the oppressive uncertainty any longer, he went to the police station.

There, in a modest office, he outlined his version of events. He spoke restrainedly, but confidently, trying not to give in to emotions. He declared his suspicions regarding Andreas and Victoria, about the incest, the fruit of which, in his opinion, was Josef. He emphasized that he had no evidence, but he could no longer ignore the rumors and his own doubts.

Kurt realized that his words could have serious consequences. He understood that an accusation of incest was a serious step, and in case of its unfoundedness, he himself could be punished. But the desire to know the truth, to get rid of oppressive thoughts outweighed the fear of possible retribution. He was ready to risk it in order to dot all the «i”s and finally gain clarity.

Kurt Wagner’s statement, like a match thrown into dry grass, ignited a new fire of scandal in the already troubled Weidhofen. The news that Andreas Gruber was again accused of incest spread throughout the district faster than the wind, accumulating new, even more shocking details along the way.

The police, under pressure from public opinion and Kurt’s insistent statements, began an investigation. Andreas was arrested and again appeared before the court, where he faced severe punishment for incest. Victoria, finding herself at the epicenter of this nightmare, was in despair. She denied all the charges, but who believed her? The shadow of the previous scandal, like sticky mud, haunted her, preventing her from justifying herself. It seemed that this sticky mud had seeped into this courtroom as well, cold as a grave, where she was to be held accountable.

The courtroom was permeated with cold, like a stone dungeon. The windows, shrouded in a gray, overcast sky, let in not a single ray of sunshine, plunging the room into semi-darkness. The air was filled with the smell of dampness and old wood, mingling with the heavy feeling of oppressive silence. The wooden benches, creaking under the weight of people, were filled to capacity. The faces of those present – serious, tense, full of anticipation – resembled stone masks. Victoria felt the piercing gaze upon herself, as if she was an exhibit in a bizarre museum.