Полная версия

The General Theory of Capital: Self-Reproduction of Humans Through Increasing Meanings

Utility and use value

Neoclassical economic theory reduced the purpose of all human activity to consumption, and the means and methods of satisfying needs to utility. Originally, it defined utility as a measure of pleasure or happiness and later as an order of preferences between alternative consumption options. However, meanings are not limited to utility—whether it is understood as pleasure, happiness or ordered preferences. Moreover, utility is not the same as pleasure: through the process of socialization, people learn to find pleasure in things that would otherwise disgust them (cf. Henrich 2016, pp. 112, 143, 345). Pleasure itself is the result of socio-cultural evolution: people form their “concept of pleasure” as they learn meanings.

Meaning can be both useful and harmful; it does not necessarily have to be associated with usefulness. Objects of needs can be useless meanings: beauty, love, justice, wisdom and many others. Meanings often are not ordered by preferences. When choosing, people take into account opportunities, risks, ethical and aesthetic norms and other meanings that are not ordered among themselves. Moreover, people do not just choose between existing alternatives. The choice process creates alternatives—counterfacts. Counterfacts are formed not only in the space of consumption options, but also in the space of consumption criteria. This means that a person not only chooses what he consumes, but the person himself is also an object of choice: rivalry of needs creates choice, rivalry of people creates selection.

We said in Chapter 1 that the three types of needs (i.e. needs of subsistence, sociality, and self-expression) did not emerge simultaneously. Perhaps it would be possible to establish an evolutionary sequence of their emergence. However, such a sequence does not mean that a person has a respective hierarchy of needs. Clayton Alderfer identified three groups of needs that have no fixed order of preference or hierarchy between them:

“…A human being has three core needs that he strives to meet. They include obtaining his material existence needs, maintaining his interpersonal relatedness with significant other people, and seeking opportunities for his unique personal development and growth” (Alderfer 1969, p. 145).

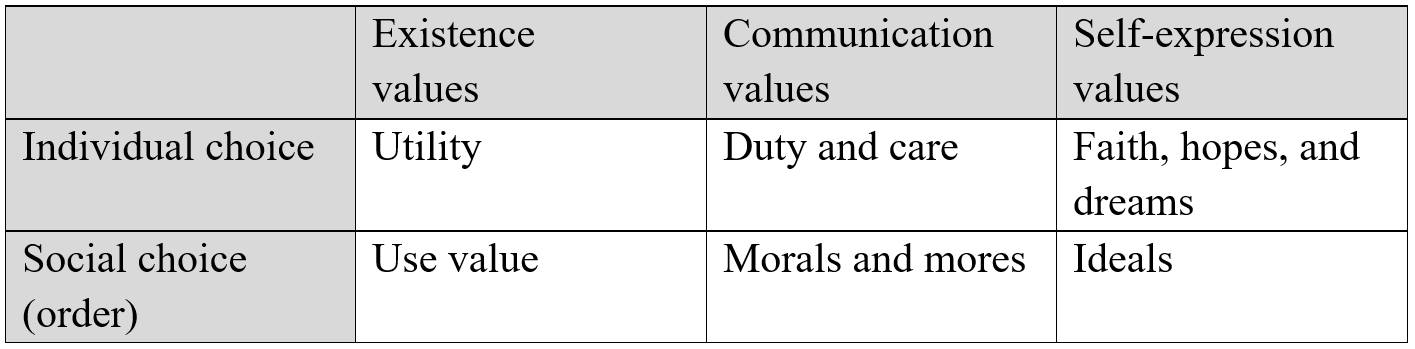

We develop Alderfer’s approach further and apply it to values as cognitive representations of needs. We identify three groups of values: existence values, communication values and self-expression values. A preference order can be found between values within these groups, but not between the groups.

Existence values are meanings that are ordered among themselves according to preferences, in which the material or utilitarian aspect dominates over social and abstract ones. For example, social status is an existence value insofar as it depends on material wealth, and not on the qualities of a person. The luxurious meal of a medieval monarch was no different from a piece of stale bread in the hands of his last subject, since it served the same purpose—the prolongation of his material, social and psychological existence. In his material existence, man is moved by the consequences of his actions, that is, by effect or utility. The animal principle in man speaks the language of efficiency.

Communication values are meanings ordered among themselves according to preferences, in which the social aspect dominates the material and abstract—for example, friendship or justice. In his social relationships, man is guided by norms, or δέοντα. The sum of the norms is a socio-cultural order. The social principle in man speaks the language of justice.

Self-expression values are meanings ordered by preferences, in which the abstract aspect dominates over the social and material—for example, dreams, fears, hopes and other creative values. In his personal development, man is guided by virtues and ideals. The cultural principle in man speaks the language of freedom.

Human action is the result not only of individual but also of social choice. A person not only pursues benefits, but also follows his duty and strives for virtues:

“To live is for man the outcome of a choice, of a judgment of value. It is the same with the desire to live in affluence. The very existence of ascetics and of men who renounce material gains for the sake of clinging to their convictions and of preserving their dignity and self-respect is evidence that the striving after more tangible amenities is not inevitable but rather the result of a choice” (Mises 1996, p. 20).

A situation in which a person must choose between utility and morality, between morality and ideal, between ideal and utility, is a situation of existential choice, a choice between conflicting groups of values. People do not maximize utility—they make individual and social choice, and in making choice they create meaning.

Illustration 3. Structure of values

It is difficult to say where cultural selection ends and social choice begins. In many cases it can be the same thing. Social choice is determined not only by the coordination of individual choices, which is often impossible in the absence of a “dictator,” but also by the presence of impersonal norms and ideals. Society is impossible without morality and sublime feelings; it is equally the result of the actions of materialists, utilitarians and pragmatists, as well as idealists, moralists and romantics. People are not reduced to identifying preferences and maximizing utility, they are not “economic” but “socio-cultural” people. Their actions are based not only on calculation, but also on mutual likes and dislikes, on duty and obligations arising from reciprocity. “Morality stems from our sentiments, not our reason” (Collier 2018, p. 35). Human actions cannot be reduced to consumption, human values cannot be reduced to utility.

If utility is an individually necessary set of existence values, then use value is a socially necessary set of these values. Utility arises from the needs and desires of individuals, use value from socio-cultural norms:

“René Girard’s hypothesis is crucial for understanding the nature of human institutions and the logic of their functioning. According to this hypothesis, institutions arise from the violence of human desire and their normalizing effect on it arises from their external relationship to the clash of conflicting desires” (Aglietta and Orléan 2002, p. 15).

Utility and use value are two complementary processes: utility is the process of individual calculation that creates culture-society, and use value is the process of social choice that creates the active power of the individual.

“…An order arising from the separate decisions of many individuals on the basis of different information cannot be determined by a common scale of the relative importance of different ends. … Order is desirable not for keeping everything in place but for generating new powers that would otherwise not exist” (Hayek 1988-2022, vol. 1, p. 79).

Use value is not a sum of occasional utilities; it is the socially necessary set of existence values. The history of production and exchange has consisted of the normalization or averaging of utilities, their transformation into socially necessary use values. In order for grain, cattle, precious metals, etc. to be transformed into use values, they had to become abstractions of utility. The end point of this process of social abstraction is commodities, exchange values, and money.

Use value, exchange value and money

In Marx’s analysis of commodity production, commodities resulting from productive activities are opposed to immediate producers. Commodities, or dead labor, dominate living labor, or the workers themselves. To analyze human history in a broader perspective than commodity production, a generalization of concepts is necessary. We generalize the concept of labor to the concept of activity (action), the concept of commodity to the result of an activity (result of an action), thus eliminating the opposition between labor and commodity and uniting them in the concept of meaning.

Marx also distinguished between the activity that creates use values, or concrete labor, and the activity that creates exchange values, or abstract labor, in which the characteristics of specific types of labor disappear:

“If then we leave out of consideration the use value of commodities, they have only one common property left, that of being products of labor. But even the product of labor itself has undergone a change in our hands. If we make abstraction from its use value, we make abstraction at the same time from the material elements and shapes that make the product a use value; we see in it no longer a table, a house, yarn, or any other useful thing. Its existence as a material thing is put out of sight. Neither can it any longer be regarded as the product of the labor of the joiner, the mason, the spinner, or of any other definite kind of productive labor. Along with the useful qualities of the products themselves, we put out of sight both the useful character of the various kinds of labor embodied in them, and the concrete forms of that labor; there is nothing left but what is common to them all; all are reduced to one and the same sort of labor, human labor in the abstract” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 48).

By abstracting from specific kinds of labor, we do not create a new kind of labor. Abstract labor and its products do not exist in themselves; they are found in concrete labor processes and their products. But if concrete labor creates use values and commodities, then abstract labor creates exchange values and money. As we have shown, use value is not an individual utility but a socially necessary set of existence values. Use value is, so to speak, a prologue to a commodity in demand on the market and its exchange value. For a commodity to have an exchange value it should have a use value, that is, satisfy socially necessary needs. Commodities are wealth because they accumulate both use and exchange values.

We will distinguish between the multiplicity and the mass of meanings. The multiplicity of meanings consists of a set of meanings. In terms of commodities, these could be: two rolls of cloth, three bulls, ten tons of steel, etc. The mass of meanings is the set of cultural bits contained in a given multiplicity of meanings. Concrete labor creates commodities, abstract labor defines their mass. As Marx said, the abstract labor that forms the substance of value is homogeneous labor. However, since at the time of Marx there was neither information theory nor the concept of the bit, he had to measure abstract labor in terms of labor time:

“A use value, or useful article, therefore, has value only because human labor in the abstract has been embodied or materialized in it. How, then, is the magnitude of this value to be measured? Plainly, by the quantity of the value-creating substance, the labor, contained in the article. The quantity of labor, however, is measured by its duration, and labor time in its turn finds its standard in weeks, days, and hours” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, pp. 48-49).

Marx measured the exchange value of a product by the amount of labor that was socially necessary to produce it, and he measured the amount of labor by its duration: “The labor time socially necessary is that required to produce an article under the normal conditions of production, and with the average degree of skill and intensity prevalent at the time” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 49). Since it is obvious that more complex labor creates more value than simpler labor of the same duration, he reduced complex labor to simple labor by applying a multiplier:

“Skilled labor counts only as simple labor intensified, or rather, as multiplied simple labor, a given quantity of skilled being considered equal to a greater quantity of simple labor. Experience shows that this reduction is constantly being made. A commodity may be the product of the most skilled labor, but its value, by equating it to the product of simple unskilled labor, represents a definite quantity of the latter labor alone” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 54).

Marx did not know, and could not have known, that there is no multiplier that can reduce a more complex meaning to a simpler one. Only later in the 20th century was it shown by information theorists that there is no such algorithm that could eliminate “redundant” figurae and compress the meaning s to the minimal action s* to find out the complexity of s:

“The difference between the length of a string L(s) and its algorithmic entropy K(s) can be thought of as a kind of “algorithmic redundancy.” It’s a measure of how many extra bits we use to write s rather than s*, its shortest description. When we go from s down to s*, we squeeze out all that redundancy, leaving none in s*. That’s what makes it algorithmically random. … A program that could do perfect data compression—that could convert any string s into its minimal description s*—would be a very useful thing. But as we will see, such a program is impossible. … The problem here is that there is no program k that can compute algorithmic entropy. K(s) is an uncomputable function” (Schumacher 2015, pp. 241-247).

Since there is no algorithm that would reduce complex labor to simple labor, time cannot be a measure of abstract labor. However, different activities and their results can be reduced to a common equivalent, if not through the concept of time, then through the concept of cultural bits. Exchange value is measured not by the duration of time but by the amount of cultural bits contained in a set of use values. Use values are socially necessary existence values; exchange values is the socially necessary amount of cultural bits embodied in these values. Hereinafter, by value we mean exchange value in the context of use values, unless otherwise specified. Meanings became value as episodic exchange has turned into regular one, as small communities cohered into larger societies, as social necessity evolved.

According to the principle of least action, changes in the socially necessary multiplicity of existence values are linked to changes in the socially necessary mass of these values. We call this relationship between the set and the mass of existence meanings ordered by preferences the allocation of meanings. It takes activity to reproduce meaning, it takes meaning to reproduce activity. Value is the allocation of the only truly limited resource people have—their actions and results, that is, meanings—between competing goals. As an allocation of meanings, value has two sides: the side of benefits (meanings gained) and the side of costs (meanings expended). The socially necessary set and mass of meanings are determined not by some average but by the best alternative allocation that is foregone:

“In economics, the cost of an event is the highest-valued opportunity necessarily forsaken. The usefulness of the concept of cost is a logical implication of choice among available options. Only if no alternatives were possible or if amounts of all resources were available beyond everyone’s desires, so that all goods were free, would the concepts of cost and of choice be irrelevant” (Alchian 1968, p. 404).

The allocation problem and the choice problem are the same. The allocation problem implies choosing between counterfacts (benefits and costs), and the value is the best allocation to forego.

Philip Mirowski wrote that the transition from classical political economy with its “labor theory of value” to neoclassical economics with its concept of “marginal utility” is associated with the transition of physics from the concept of “substance” to the concept of “field” and with the penetration of mathematical methods into economic theory (Mirowski 1989, pp. 176-177, 194-195). If classical political economy and neoclassical economics considered physics as a model, then the economics of the 21st century is guided for this purpose by the sciences of information, evolution, and complexity. The theory of marginal utility reduced value to the perception of utility by a person and did not take into account social necessity. This theory was unable to establish an objective measure of economic indicators, in particular, it could not measure utility and show how and why utility depends on social mores and ideals. The concept of value as a socially necessary multiplicity and mass of existence values is a generalization of two competing theories of value: the classical labor theory of value and the neoclassical theory of marginal utility.

Exchange value is an abstract phenomenon that cannot be observed directly. But value has a tangible representation, its history can be traced through the history of money, since money is the material expression of value and a social instrument for calculating the necessary set and mass of existence values.

Money and prices

Money is both a process and a result of the historical evolution of economic calculation. As a material expression of exchange value that links past and future activities, money evolves through the entire sequence of forms of circulation from gifts and tribute to commodity exchange. The first function of money is a means of calculation and circulation. In a subsistence economy, calculations are carried out directly, the quantity and allocation of activities are directly linked to the future consumption of their products. Money appears in tribal societies as an indirect way of accounting for gifts and tribute: one can recall the rai stones on the Yap Islands. In a tribal society, however, money does not link production and consumption, past and future activity. Truly methodical calculation began with the advent of the state with its accounting and planning. The Chessboard Chamber controlled the treasury of medieval England using simple means such as checkered cloth and wooden tokens.

Value is a measure of the socially necessary activity and its results, money is the material expression of value. In practical terms, money is both a means of calculating value on the basis of the individually necessary amounts of activity and a means of calculating the consumption share of individuals and groups. Value is a socio-cultural phenomenon, and money and prices are a technology that builds on the programming of this phenomenon and mediates the evolution from the simplest to more complex forms of exchange.

Individual needs can only coincide with socially necessary needs by chance, otherwise individuals would be only an external manifestation of society as a kind of “superorganism.” Thus, the totality of individually necessary meanings can only coincide with the totality of socially necessary meanings by chance. In the general case, the aggregate of individually demanded goods and their prices should not be equal to the set of use values and their exchange values. “Through the mediation of money, subjects maintain relationships with what is not themselves, with the social as an institution” (Aglietta and Orléan 2002, p. 19).

Exchange value is the substance of money; price is the sum of money that an individual consumer, producer or intermediary is willing to pay for a given good. Exchange value is the measure of use value, price is the measure of utility. Although the meanings of existence are ordered among themselves, they are not ordered with the meanings of communication or self-expression. Exchange value is not the measure of dreams, morals and ideals, they cannot be bought with money. But exchange value and money are impossible without dreams, morals and ideals, since they make social choice possible and hence social necessity and value as a socially necessary mass of cultural bits embodied in use values. Loves and hopes, morals and ideals are not for sale, money is not paid for them. But goods are sold (or not sold) at a price determined with loves and hopes, morals and ideals in mind.

Value as a socially necessary mass of use values evolves in the process of self-reproduction of culture-society, while price as an individually necessary mass of utility develops in scattered acts of individual or collective self-reproduction. Value and price are linked through money: “Economists have the habit of thinking about prices starting from value, while for us their basis is to be found in money” (Aglietta and Orléan 2006, p. 27).

The evolution of value and money, commodities and prices depends on the evolution of meanings in general. The increase of meanings is manifested in their complication: division, addition and multiplication. The opposite is also true: the evolution of value and money, commodities and prices is a prerequisite for the evolution of all other meanings, since circulation is a necessary phase of the self-reproduction of culture-society. The complication of competition, cooperation and administration is necessary for socio-cultural development. Activity, order and knowledge are divided by purposeful choice and by spontaneous cultural selection:

“The price system is just one of those formations which man has learned to use (though he is still very far from having learned to make the best use of it) after he had stumbled upon it without understanding it. Through it not only a division of labor but also a co-ordinated utilization of resources based on an equally divided knowledge has become possible” (Hayek 1988-2022, vol. 15, pp. 101-102).

With the advent of money, people had the opportunity to hoard it instead of spending it on goods, that is, not to consume goods but to store value and spend it later. The second function of money is therefore a means of accumulation, that is, a vehicle for saving and investing value. Money is a way to establish a relationship between a resource and the future costs and benefits it brings.

Since money is both a means of calculation and circulation and a means of saving and investing, it requires, first, cooperation and trust, that is, an agreement between subjects, and, second, administration and coercion, that is, institutions that ensure compliance with this agreement. Money and the state formalize the duties and obligations of members of society. Money is a horizontal way of formalizing mutual obligations. The state is a vertical way of formalizing the responsibility of the individual to society as a whole.

Originally, money had to have the properties of utility and scarcity, later it also had to be portable, divisible and long-storable, which is why precious metals were used as currency. As money evolved, it shifted from hard material form to abstract social content, from gold or silver coins to fiat money.

2. Profit and interest

Surplus activity and its norm

A culture-society reproduces itself through added activity. A hunter-gatherer society, with its modest cultural experience and comparatively low complexity of meanings, produced activities that only enabled it to reproduce itself on a constant scale. The added activity of a primitive society was approximately equal to the sum of the necessary activity of the individuals who composed it. The accumulation of cultural experience, the division, addition and multiplication of meanings during the transition to agriculture, enabled the culture-society to carry out more complex activities and to produce more means of activity—more than was required for the simple reproduction of the active power of the individuals:

“At the dawn of civilization the productiveness acquired by labor is small, but so too are the wants which develop with and by the means of satisfying them. Further, at that early period, the portion of society that lives on the labor of others is infinitely small compared with the mass of direct producers. Along with the progress in the productiveness of labor, that small portion of society increases both absolutely and relatively” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 513).

In its ability to give more than it gets, a producing culture-society resembles nature. Just as the land can produce a harvest in excess of the amount sown, so an agrarian culture-society can produce more than is required for its self-reproduction. However, an agrarian culture-society is not able to maintain stable productivity, let alone stable productivity growth. Due to sudden changes in both socio-cultural and environmental conditions, population growth could be replaced by a sharp decline. Epidemics and crop failures led to the collapse of cultures-societies, that is, to a drop in their complexity. The ascending and descending phases of the demographic cycle replaced each other: