Полная версия

The General Theory of Capital: Self-Reproduction of Humans Through Increasing Meanings

According to Thomas Malthus, in a traditional society, the population grows geometrically, while food production grows arithmetically. Geometric population growth with arithmetical production growth is a path to the Malthusian trap, that is, to the crisis and death of the entire society or that part of it that cannot feed itself. An agrarian society remains, to a large extent, part of its natural environment: the development of its meanings constantly encounters natural constraints—be they environmental disasters, crop failures or epidemics.

Quality and quantity of meanings

Meanings change according to the laws of probability. On the one hand, they can increase and complicate when people (re)combine them trying to get different results. On the other hand, they can decrease and simplify when people lose them during transmission. Culture is an ongoing experiment based on experience:

“Larger populations can overcome the inherent loss of information in cultural transmission because if more individuals are trying to learn something, there’s a better chance that someone will end up with knowledge or skills that are at least as good as, or better than, those of the model they are learning from. Interconnectedness is important because it means more individuals have a chance to access the most skilled or successful models, and thereby have a chance to exceed them, and so can recombine elements learned from different highly skilled or successful models to create novel recombinations”(Henrich 2016, p. 220).

The quality and quantity of meanings depend on the strength, diversity and sociality of human populations, and population numbers depend on the quantity and quality of meanings:

“… If some one man in a tribe, more sagacious than the others, invented a new snare or weapon, or other means of attack or defense, the plainest self-interest, without the assistance of much reasoning power, would prompt the other members to imitate him; and all would thus profit. The habitual practice of each new art must likewise in some slight degree strengthen the intellect. If the new invention were an important one, the tribe would increase in number, spread, and supplant other tribes. In a tribe thus rendered more numerous there would always be a rather better chance of the birth of other superior and inventive members” (Darwin 1981, p. 161).

The same mechanisms that lead to an increase in the complexity of a culture-society can, under certain conditions, also lead to a loss of complexity. When a population shrinks or gets isolated, it can lose its adaptive cultural information. Joseph Henrich gives the following example. When Europeans first encountered Tasmanians, their tools looked primitive compared to the tools of other Paleolithic communities. Archaeological excavations have shown that Tasmanians had more complex instruments tens and even hundreds of thousands of years ago, until about 12,000 years ago, when the island was cut off from Australia by rising sea levels. Under conditions of isolation, Tasmania’s relatively small population was unable to maintain the previous complexity of its tools (Henrich 2016, pp. 220-222).

Human activity is a set of material social abstract actions, the result of which are humans themselves. The quality of meanings determines the quality of people, and the quality of people determines the quality of meanings. In this “subject—meaning” cycle, the quality of both the subject and the meaning is determined by their materiality, sociality and abstractness. The quality of material action (making) and its means depends on the community size and the specifics of communication:

“The size of the group and the social interconnectedness among these individuals plays a crucial role in this process. The most obvious way that the size of a group can matter is that more minds can generate more lucky errors, novel recombinations, chance insights, and intentional improvements” (Henrich 2016, p. 213). “The power of a group’s collective brain depends on its social norms and institutions. … In humans, sociality and technological know-how are intimately interwoven” (ibid., p. 322).

Both materiality and sociality are closely related to abstractness, that is, the ability to understand causes and motives, to calculate and compute in the broadest sense. In primates, the size of the prefrontal cortex depends on the community size: the more social connections, the larger the cortex (Sapolsky 2017, p. 51). The mind is the same layering of different periods and epochs as the brain. We can trace the entire sequence from the oldest to the later elements and functions in it:

“Thus, in looking at a bacterium under the microscope, it answers with a continuous ‘computo ergo sum.’ One has to know how to listen. But what could it mean to say, ‘I compute for myself?’ It means that I place myself at the center of the world, the center of my world, the world that I know, to process it, to consider it, and accomplish all the measures of protection, defense, etc. It is here that the notion of the subject makes its appearance, along with the computo and its egocentrism. The notion of the subject is indissociable from this act of computation, where one is not only one’s own finality, but where one also constitutes one’s own identity” (Morin 2008, p. 73).

In living nature, a subject arises where “biomechanical calculation” takes place. In a culture-society, a subject (an economic unit) arises where “economic calculation” begins. A Paleolithic clan community, a king’s court, a modern firm are economic units. Calculation or choice is an evolutionary process that evolves within human self-reproduction and ensures its continuation. As a comparison of past, present and future costs and benefits, calculation preceded any production: a community of hunters and gatherers had its own way of calculation and its own relationship of individuals, based on this way. Indirect reciprocity is a method of calculation in which after a successful hunt, the prey was divided among all members of the clan. This secured a share of the pray in case of an unsuccessful individual hunt and solved the problem of storing the excess meat (Sapolsky 2017, pp. 324-325). The growth of agricultural production expanded the range of man-made values that were not present in nature but were necessary for the self-reproduction of human communities. This increased the importance of economic calculation and governance, that is, the role of reason compared to that of instincts and practices.

Man is both the subject and the object of his own activity, nature and culture are its means. “The elementary factors of the labor process are 1, the personal activity of man, i.e., work itself, 2, the subject of that work, and 3, its instruments” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 188). To these factors one must add man himself as the driving force of activity and his needs as the source of this driving force. The evolution of meanings is associated with the unfolding of needs and the development of material, social and mental values. As we said above, values are, on the one hand, a representation of needs in the minds of people, and on the other hand, a projection of needs onto things and circumstances. “Value is not intrinsic, it is not in things. It is within us; it is the way in which man reacts to the conditions of his environment” (Mises 1996, p. 96). Projections can be positive and negative, good and evil.

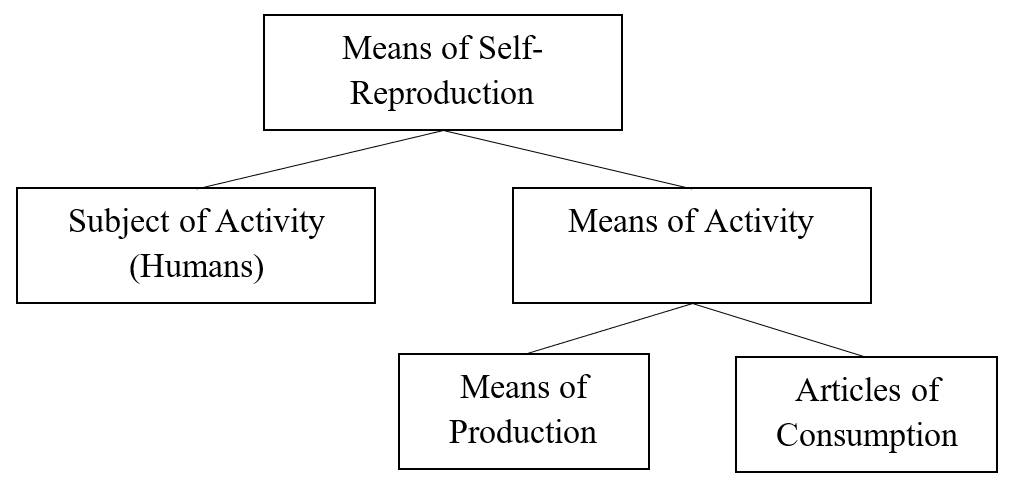

As the driving force of activity, man is an active power. Man reproduces himself through activities that consist of an immense quantity of actions. Meanings increase in cumulative cultural evolution by being divided, added and multiplied. Human activity accumulates more and more meanings; its starting point and result are man himself (his active power) and the means of his activity. Man and the means of activity together form the means of self-reproduction. The means of activity, in turn, are divided into means of production and means of consumption (consumer articles). In the course of agricultural evolution, the means of production gradually separated from consumer goods, and the experience of appropriating the creations of nature was supplemented by the experience of creating the products of culture.

Illustration 2. Means of self-reproduction

Unlike consumption, production does not aim at satisfying immediate needs, but at satisfying indirect, future needs. Economists traditionally reduce means of activity to goods. According to Carl Menger, lower-order goods aim at satisfying human needs (consumer goods), and higher-order goods (means of production) aim at producing lower-order goods in the future: “Goods of higher order acquire and maintain their goods-character, therefore, not with respect to needs of the immediate present, but as a result of human foresight, only with respect to needs that will be experienced when the process of production has been completed” (Menger 2007, pp. 81-82). In fact, however, means of activity are not reduced to goods, since people consume not only goods, but also evils (both productive and non-productive).

Besides their ability to satisfy human needs (directly as consumer articles or indirectly as means of production), means of activity have in common the fact that they are themselves products of activity. Marx introduced the concept of “abstract labor” in volume I of Das Kapital (1867) to bring all concrete types of activity to a general equivalent so that the quantity of labor can be calculated: “If then we leave out of consideration the use value of commodities, they have only one common property left, that of being products of labor” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 48).

Marx introduced the concept of “abstract labor” but did not explain what its substance is. Georg Simmel wrote in his The Philosophy of Money (1900) that unlike energy, which is essentially unchanging but can manifest itself in different ways (such as heat, electricity, mechanical motion), different types of labor do not have a general equivalent or substance that would allow comparisons between, for example, “muscular” and “mental” labor. At the same time, Simmel admitted that such an equivalent might exist:

“From the outset I admit that I do not simply rule out the possibility that in the future the mechanical equivalent for the psychic activity will be discovered. Of course, the importance of its content, its factually determined position in logical, ethical and aesthetic contexts is completely separate from all physical movements, roughly in the same manner as the meaning of a word is quite separate from its physiological-acoustic sound. Yet the energy that the organism must expend upon the thought of this content as a cerebral process is, in principle, just as calculable as that necessary for a muscular exertion. If this were to be achieved one day, then one could at least make the amount of energy necessary for a specific muscular exertion a unit of measurement on the basis of which the mental use of energy would be determined. Mental labor would then be dealt with on the same footing as manual labor, and its products would enter into a merely quantitative balancing of value with those of the latter” (Simmel 2004, p. 421).

As Simmel correctly assumed, the general equivalent that makes it possible to treat mental and manual labor on the same footing is not mechanical in nature. Nor is it energy or time. Rather, it is directed information: meaning is the sought-after substance of all human activity and its results.

Figurae as elements of meaning

As a building block of culture, meaning is social information in action. In genes, information is recorded in the form of nucleotide sequences. How then is information recorded in meanings? An individual meaning is made up of figurae—changes and differences. Meanings consist of both continuous and discrete figurae. Meanings are therefore similar to light, which has a wave-particle nature.

The quantity of meaning is determined by the number of figurae, or changes and differences. It applies to all functions of meaning—be it making and things, communication and communities, thinking and symbols. The quantity of meaning is in all cases determined by the number of figurae necessary for its reproduction. It is impossible to reduce meaning only to expression, only to content, or only to a norm, since every meaning is a material and social abstraction in action, taken in the unity of all the changes and differences necessary for its reproduction. As a social and material abstract action, meaning is based on the expenditure of energy and time. However, energy and time are constraints, not measures of meaning. Its quantity is measured by the number of figurae it contains.

Information theory calls changes and differences bits and measures information in bits. A bit is a change or difference that is reduced to being a change or difference and nothing else: “1” or “0,” “on” or “off,” etc. The simplest element of meaning, the simplest figura, is not just a bit (“0” or “1”) but a bit that has a valuation attached to it. The cultural bit has not only a modulus (“0” or “1”), but also a sign (“+” or “–”). Information is certainty, meaning is directed, value-based information. A meaning can be visualized as a string s consisting of figurae. The criterion for defining the size or quantity of the meaning is the number of figurae in the string s.

A string of figurae forms a meaning, a bundle of meanings forms a context. Since meanings exist in context, they function not as a discrete, but as a continuous set. There is no clearly defined, fixed boundary between figurae and meanings; this boundary is mobile and is determined by the context. The same human movement can, depending on the context, be either part of an action or an independent action with its own meaning—a gesture. Every meaning acquires its specifics in context. Meaning is always a specific action and the result of such an action. An abstract expression is a meaning only insofar as it is found in the context of concrete social actions.

Aristotle said that “art in some cases completes what nature cannot bring to a finish, and in others imitates nature” (Aristotle 1984, vol. 1, p. 340). Completeness or perfection is the main characteristic of a meaning and of culture as a whole, as compared to figurae. A finished biface is a meaning, a stone fragment is a figura. A finished phrase is a meaning, an unfinished phrase is an assortment of figurae. A well-thought-out book is a meaning; an ill-thought-out book is an assortment of figurae. Wisdom is the highest form of completeness of an action, enabling one to begin a fundamentally new action.

The relationship between figurae and meanings in their linguistic (symbolic) forms, a kind of “sense of meaning,” is the basis of the common language of all humans, which enables us to learn new languages in adulthood and to guess the purpose of rubble found during archaeological excavations. “Such non-signs as enter into a sign system as parts of signs we shall here call figurae; this is a purely operative term, introduced simply for convenience. Thus, a language is so ordered that with the help of a handful of figurae and trough ever new arrangements of them a legion of signs can be constructed” (Hjelmslev 1969, p. 44).

When we say that bits are “building blocks” of information, and figurae are “building blocks” of meaning, we imply that figurae, unlike bits, have qualitative properties and that the set of figurae can be divided into subsets, or that we can distinguish between basic types of figurae. This applies to meanings as such, but it was first noted for linguistic signs. Hjelmslev considered the identification of these types to be a necessary condition for understanding both the expression and the content of languages.

“Such an exhaustive description presupposes the possibility of explaining and describing an unlimited number of signs, in respect of their content as well, with the aid of a limited number of figurae. And the reduction requirement must be the same here as for the expression plane: the lower we can make the number of content-figurae, the better we can satisfy the empirical principle in its requirement of the simplest possible description” (Hjelmslev 1969, p. 67).

As we saw above, meanings are not reduced to signs and symbols. Meanings manifest themselves in the mental, social and physical existence of a person, but meanings are not born in this existence. Abstractions are not a product of the human intellect, neither in its affirmative form of understanding nor in its negative form of reason. Rather, it is understanding and reason that are the result of the evolution of social and material abstractions in action. Meanings only reproduce fundamental definitions, states, relationships, changes, directions in nature and society: “If we’re able to learn language from a few years’ worth of examples, it’s partly because of the similarity between its structure and the structure of the world” (Domingos 2015, p. 37). Hence the universality of meanings, the ability of people to understand each other, to translate each other’s languages—and this after tens of thousands of years of isolated life. During the Age of Discovery, Europeans found a common language with the Indians or Australians. All people act, talk and think in one language—the language of meaning:

“In Leibniz’s view, if we want to understand anything, we should always proceed like this: we should reduce everything that is complex to what is simple, that is, present complex ideas as configurations of very simple ones which are absolutely necessary for the expression of thoughts” (Wierzbicka 2011, p. 380). “…’Inside’ all languages we can find a small shared lexicon and a small shared grammar. Together, this panhuman lexicon and the panhuman grammar linked with it represent a minilanguage, apparently shared by the whole of humankind. … On the one hand, this mini-language is an intersection of all the languages of the world. On the other hand, it is, as we see it, the innate language of human thoughts, corresponding to what Leibniz called ‘lingua naturae’” (ibid., p. 383).

Mathematics as a domain of meaning is also a reflection of the fundamental definitions of the world. The similarities between the world and mathematics make it possible to solve scientific problems. This similarity did not arise overnight. Mathematics is a result of the evolution of meaning from the order of the universe up to the reflection of this order in the minds of people. On the scale of millions and billions of years, the difference between Turing and Wittgenstein disappears: “Turing thought of mathematics as something that was essentially discovered, something like a science of the abstract. Wittgenstein insisted that mathematics was essentially something invented, following out a set of rules we have chosen—more like an art than a science” (Grim 2017, p. 151). In fact, both mathematics and logic in general are the result of cultural evolution that occurs through selection and choice. It could be, that the logical contradiction between meanings expresses the historical and practical discrepancy of meanings in relation to the environment and the subject, and the resolution of such a contradiction reflects the overcoming of this discrepancy.

The simplicity of early meanings did not only concern making. Thinking and communicating were just as simple, relying on crude motions of body and mind. Primitive making has left us its direct results: stones, bones, etc. Unfortunately, the direct products of communicating or thinking no longer exist, so we can only judge them indirectly. In the process of social and then cultural learning, as the norm of first learned and then rational reaction expanded and cultural selection turned into traditional choice, the complexity of meanings and of the culture-society as a whole increased, as did the number of figurae and meanings.

The gradual complication of meanings becomes clear, for example, when we consider the evolution of stone tools: from the simplest Paleolithic choppers to the polished and drilled Neolithic axes, which are characterized by a much higher level of workmanship. Cultural evolution consists in the division of meanings, that is, in the emergence of ever new types of actions and their results. By dividing their activity and knowledge, people specialized in those types of actions in which they had a competitive advantage due to the characteristics of the environment or their active power. Hunting and gathering divided into farming, herding, crafts, trade. Not only the complexity of making grew, but also of communicating and thinking. Languages were more complex. Learned actions became a more important part of self-reproduction relative to instinctive behaviors, rational actions grew more vital relative to learning.

2. Complexity of meaning

Minimal subject and minimal action

That the complexity of meanings increases as they evolve may be intuitively obvious, but it was only in the middle of the 20th century that the concepts of the quantity of information and information complexity were rigorously substantiated in the works of Claude Shannon and Andrey Kolmogorov.

Shannon introduced the concept of information entropy. According to him, entropy H is a measure of the uncertainty, unpredictability, surprise or randomness of a message, event or phenomenon. In terms of culture, such a message or event is a counterfact. Without information losses, Shannon entropy is equal to the amount of information per message symbol. The amount of information is determined by the degree of surprise inherent in a particular message:

“According to this way of measuring information, it is not intrinsic to the received communication itself; rather, it is a function of its relationship to something absent—the vast ensemble of other possible communications that could have been sent, but weren’t. Without reference to this absent background of possible alternatives, the amount of potential information of a message cannot be measured. In other words, the background of unchosen signals is a critical determinant of what makes the received signals capable of conveying information. No alternatives = no uncertainty = no information. Thus Shannon measured the information received in terms of the uncertainty that it removed with respect to what could have been sent” (Deacon 2013, p. 379).

Thus, the average amount of information H a culture-society contains can be measured by the number of (counter)facts it generates and the probability of their occurrence. The Shannon entropy H is an indicator of the complexity of a culture-society as a whole. If we look at the history of human cultures-societies, we see that their complexity has consistently grown: from a meager set of primitive meanings (tribal community, elementary language, simple stone tools, causal mini-models, animism and fetishism) to a complex arsenal of meanings characteristic of agrarian societies (fields and livestock, agricultural and craft tools, city-states and empires, writing and literature, ancient and Arabic science, world religions).

Cultural evolution has increased the complexity of entire cultures-societies as well as individual meanings. As mentioned earlier, the complexity of a meaning is determined by the minimum number of figurae required to reproduce it. Suppose we have a meaning s that can be represented as a string with a certain number of figurae. The length of this string is L(s). In this case, the complexity of a meaning s is defined by the length of the shortest program s* that can describe this meaning. The length of the program s* is called the algorithmic entropy of s or Kolmogorov complexity K(s):

“The key concept of algorithmic information theory is that of the entropy of an individual object, also called the (Kolmogorov) complexity of the object. The intuitive meaning of this concept is the minimum amount of information needed to reconstruct a given object” (Vinogradov et al. 1977-1985, vol. 1, p. 220).

We call the program s* the least or minimal action necessary to reproduce the meaning s. The complexity of the meaning s depends on the length (size) of the minimal action required to reproduce it. For example, the string asdfghjkl can be described only by itself. Its length is 9 non-repeating figurae. However, if a string s has a pattern—even a non-obvious one—it can be described by a minimal action s* that is much shorter than s itself. For example, the string afjkafjkafjkafjk can be described by the much shorter string afjk repeated as many times as necessary.