Полная версия

The General Theory of Capital: Self-Reproduction of Humans Through Increasing Meanings

Meaning is a means that has evolved into an end. Ends and goals are the results of possible actions that subjects imagine. The ability to set goals, that is, to imagine means and to choose between them, distinguishes humans from animals, which also use the environment as a means.

“A spider conducts operations that resemble those of a weaver, and a bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labor process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the laborer at its commencement” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 188).

The evolution of meanings began with the simplest actions and their results, such as the making of a chopper. The simplest chopper—a stone whose edge has been sharpened by chipping off fragments with another stone—is the result of the motions of a hominid. The sum of the motions forms a holistic action, the result of which is the chopper. A hominid, his instrumental action, and chopper itself are necessary for meaning to emerge. The moment when hominids began deliberately making choppers was also the moment when nature became their means and culture emerged. It is obvious that this “moment” is actually a bridge across time, and the spans of this bridge require further exploration.

Ants of the Attini family grow Basidiomycota fungi that process leaves they cut. The ants in turn feed on the protein-rich “ant kohlrabi” that grows on the fungi. Ants do not just use means, but engage in a whole “craft,” a kind of “agriculture.” However, the ants’ activities remain within the limits set by their genetic program. Their behavior changes only as their instincts evolve, and it cannot change through the inheritance of learning-based practices. Human behavior can change through practice: learning creates understanding, understanding creates choice. Unlike ants, humans imagine things before they act: “new technologies are constructed mentally before they are constructed physically” (Arthur 2011, p. 23).

Animals do not have ends or means, but they do have wants or needs. Need is the focus of a living being on something that does not exist. “In its primary biological forms, need is a state of the organism expressing its objective want for a complement that lies outside itself” (Leontiev 1971). Terence Deacon introduced the concept of “entention,” which can be considered a kind of generalization of the concept of “need.” Entention combines direction and lack, it is “a fundamental relationship to something absent” (Deacon 2013, p. 27). The object to which the need is directed is the motive.

“…Motives must be distinguished from conscious goals and intentions; motives ‘stand behind goals’ and stimulate the achievement of goals. If goals are not directly given in the situation, motives encourage goal formation. However, they do not generate goals, just as needs do not generate their objects” (Leontiev 1971).

Emotions are internal signals that reflect the relationship between motives and activities caused by motives. Alexey Leontiev reduced emotions to a reflection of meaning: “Emotional processes include a broad class of processes of internal regulation of activities. They perform this function by reflecting the meaning of the objects and situations that affect the subject, their significance for his life” (Leontiev 1971). It seems to us that this is not quite correct historically, because if meanings preceded emotions, then monkeys would be like robots, and we would now need to look not for a bridge from emotions to meanings, but for a bridge from meanings to emotions. In fact, meanings arose from emotions. Emotions still are a large part of the content of meanings, if only because they reflect processes in the body. “Primordial emotions are the subjective element of the instincts which are the genetically programmed behavior patterns which contrive homeostasis. They include thirst, hunger for air, hunger for food, pain and hunger for specific minerals etc.” (Denton et al. 2009). Meaning is a symbolization and mediation of emotions.

In humans, emotions, as one of the origins of meaning have gone beyond the instinctive response to signals: in the long evolutionary process of mediation, the emotional content of meanings has been partly rationalized so that meanings and emotions form a unity. Humans do not have meaningless emotions: they explain emotions in order to understand them. Meaning, in turn, has a certain emotional significance. This significance comes to the fore in values as meanings ordered by preference: Milton Rokeach called values “cognitive representations and transformations of needs” (Rokeach 1973, p. 20).

This understanding of values emphasizes their reflected and mediated nature. There is also another understanding that seeks to emphasize the continuity between the biological and the cultural in humans, according to which needs and values (as representations of needs) are not an exclusive feature of humans, but are inherent in all living beings: “Value is a more abstract category than organisms, since it is the one thing that all organisms pursue” (Frisina 2002, p. 217). Values are both subjective and objective phenomena: they are given to humans in their imagination and in their being. For the subject, the circumstances of the environment, things, events all appear as values: positive (goods or opportunities) or negative (evils or risks).

Human feelings—both direct perceptions and emotions as motive-oriented feelings—are always meaningful, they are to some extent abstract or mediated. Meanings, in turn, are to some extent sensory, they are always concrete or material. The dual nature of meaning as generalization and feeling is evident in etymology. We use the terms “meaning” and “sense” synonymously, since in Russian there is a word for both: smysl. The sensory and concrete side of smysl (sense) is indicated by its etymological origin in some European languages, where it is derived from “feeling.” The abstract and communicated side of smysl (meaning) becomes clear in Russian word smysl that is derived from “think,” “we send” (Chechulin 2011).

At the same time, motives and sociality are what distinguish meaning from mere information without sense and direction. The concept of information and the information science itself may have emerged when people began to view nature as a specific part of culture that has no agency or subject in itself.

Those motives, emotions and ideas that do not find expression in the results of an individual’s activities remain forever hidden in the depths of his mind. They do not exist for society and do not constitute meaning. They remain mental facts or mental processes that exist only for the subject of these motives, emotions and ideas. This is one extreme at which meaning disappears. The other extreme is when meaning degenerates into a dead result, detached from the society of people, their motives, emotions and ideas. In this case, it turns into a material abstraction and loses all meaning, becomes an empty artifact, an incomprehensible archaeological find. For example, any written symbol has meaning only when it is involved in human activities, that is, when it has a subjective side. Since the symbols of the Minoan Linear A script cannot be “involved” in our activities, in our context, they remain undeciphered.

The structure of culture

Mental facts and artifacts are extreme points at which all meaning vanishes. They point to two fundamental properties of meaning: determinateness (certainty) and direction. Where one of these properties disappears, the meaning itself is lost.

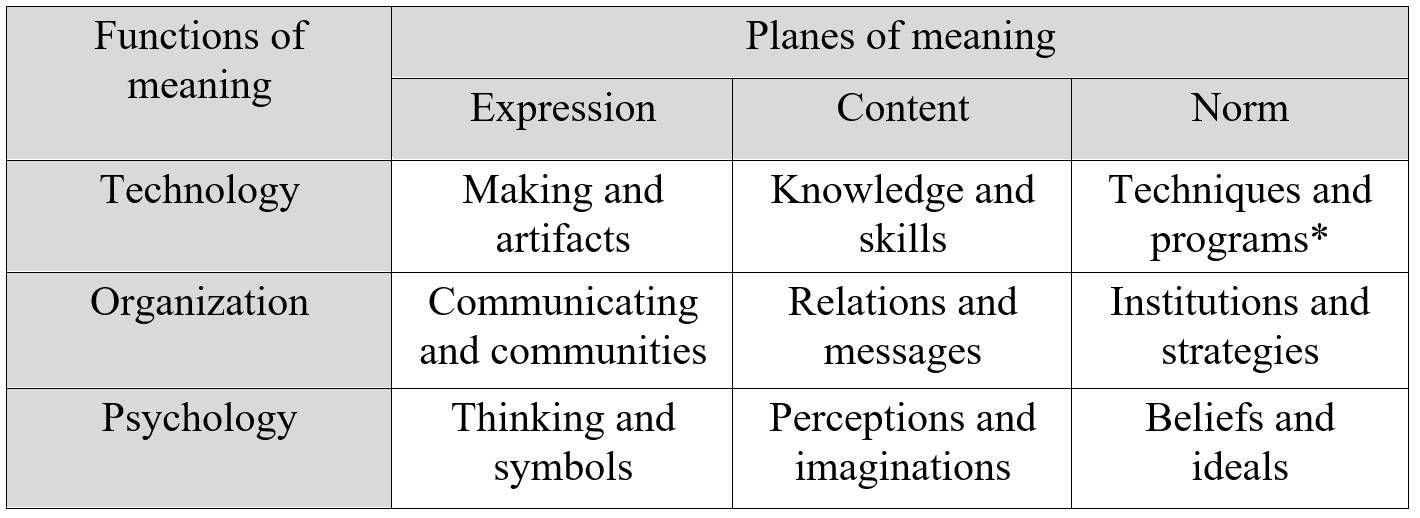

Depending on the direction (towards things, people or ideas), three sides of meanings can be distinguished: (1) material action, or making; (2) social action, or communicating; (3) abstract action or thinking. The identification of these three directions in human culture is in itself the result of the accumulation of meanings, of cultural evolution. Each direction has its own function: making is translated into technology, communicating into organization, thinking into psychology.

Depending on the determinateness, three planes of meaning can be detected: content, expression and norm. Meaning is inextricably linked to natural language. As Roy Harris said, a language community is not a congregation of talking heads, a tongue cannot be considered in isolation from the physical actions of humans. Humans are not just language-users, but language-makers (Harris 1980, preface). If humans make language through their actions, the opposite is also true—they define their actions through language. The idea of distinguishing between the planes of content and expression in languages comes from Louis Hjelmslev’s Prolegomena to a Theory of Language (1943). We develop his idea further:

● First, the environment is reflected in humans, their instincts, practices and intellects, thus forming the content of meanings. The plane of content embraces the significance of meanings. Meaning as such is often identified with the signification or signified. However, although the signified is in some ways closest to the human mind, meaning cannot be reduced to it.

● Second, humans, their motives, preferences and goals are reflected in the environment, shaping the expression of meanings. The expression plane contains signs as material aspects of meaning or signifiers. Man himself as a biocultural being, as a product of both biological and cultural evolution, is also to some extent an expression of meaning.

● Third, stable moments of interaction between humans and the environment are reflected in human activity and its results, forming its norms. The norms plane compiles the stable ways of functioning or principles and rules of meanings.

Three functions and three planes of meaning reveal the structure of culture. The following “table” demonstrates the nodal points at which functions and planes of meaning overlap. We do not give detailed explanations for the “table,” but invite the reader to look into it for himself. It should be noted that the actual structure of culture is of course much less ordered than shown in the “table,” which only serves to simplify and visually explain our theses.

Illustration 1. The structure of culture

* Programs and techniques are understood here in the broadest sense, like any program and any method of material action. W. B. Arthur uses the term “design” in this case (Arthur 2011, p. 91).

The initial stage of the evolution of meanings was characterized by a small variety of actions and their results. Stone and wooden tools, rules of nomadic life, knowledge and skills of hunting and gathering, simple oral language and fetishistic ideas made up the meager stock of Paleolithic meanings. The actions of Paleolithic man were limited to the appropriation and consumption of natural objects, and the means of his activity were reduced to consumer articles. He was just beginning to form a cultural niche, his home in the natural environment.

2. Uncertainty, selection and learning

Uncertainty and meaning

Reality is given to man through his actions. Uncertainty is the degree of adaptation (or, what is actually the same thing, inadaptation) of human needs and actions to reality. It is the discrepancy between reality and human needs. Complete adaptation would mean that the satisfaction of needs does not require human actions, in which case there would be no uncertainty at all. In practice, however, there are hardly any situations of complete certainty, so that man must act. Frank Knight argued that human wants are those needs that cause goal-directed action.

“We ‘need’ iodides and vitamins, and an infinite number of things of whose existence the race at large has been blissfully ignorant; but we do not ‘want’ them, because they give rise to no conflicts and hence no ‘conduct.’ The common basis of conflict, and we may say of the existence of wants at all, is the limitation in the means of gratifying some impulse or need” (Knight 1964, p. 60).

In school economics, uncertainty comes down to limited resources, to a lack of resources compared to human needs. But resource scarcity is just a special case of uncertainty. Another case is, for example, asymmetric knowledge, when one person knows something that another person does not know and uses this to deceive. Both are just special cases of uncertainty, that is, randomness, surprise, unpredictability.

Meaning as determinateness aims to adapt people and reality to each other, to overcome uncertainty. This gives meanings a great deal of inertia: people prefer to adapt and interpret meanings rather than abandon them. Talcott Parsons wrote that interpretation is the reason why sudden changes in the environment do not lead to the abandonment of the “symbolic formulae” and “elements of cultural tradition” on which social systems are based. Parsons (1964, p. 296) called this mechanism “adaptation by interpretation.” This mechanism has a long history that probably goes beyond humans: practices are derived from traditions and values of animals, simple causal models are older than intelligence itself:

“… Morality derives from values, rather than reason. Jonathan Haidt has found evidence for just this dominance. People try to justify their values by citing reasons for them, but if our reasons are demolished we conjure up others, rather than revise our values. Our reasons are revealed as a self-deceiving charade, a sham called ‘motivated reasoning.’ Reasons are anchored on values, not values on reasons” (Collier 2018, p. 35).

The inertia of meanings leads to the formation of stable meanings—norms—and to the creation of a socio-cultural order consisting of these norms. Meanings in their normative mode are those traditions and “social contracts” that enable society to function as a single whole. Order is constantly undermined by changes in the environment. In the early stages of cultural evolution, when the environment was still largely reduced to nature, order responded mainly to events and phenomena in the natural habitat. Adaptation to the environment occurs faster than the adaptation of the environment to human needs (Livi Bacci 2000, p. 4). Appropriation and consumption precede production. However, as the cultural niche expanded and developed into a cultural environment, order too had to change under the influence of cultural events and phenomena. Over time, cultural events have occurred more frequently and became increasingly unpredictable.

“Economists, typically, do not ask themselves about the structure that humans impose on themselves to order their environment, and therefore reduce uncertainty; nor are they typically concerned with the dynamic nature of the world in which we live, which continues to produce novel problems to be solved. The last point raises a fundamental issue. If we are continually creating a new and novel world, how good is the theory we have developed from past experience to deal with this novel world?” (North 2005, p. 13).

Events and phenomena are a source of uncertainty. From the perspective of order, an event is news if it represents a deviation from the norm: “An occurrence, a meaningful departure from the norm, (that is, ‘news,’ since the fulfillment of a norm is not ‘news’) depends on one’s concept of the norm” (Lotman 1977, p. 234). The socio-cultural order aims to eliminate uncertainty of events by transforming them into facts (patterns of events) and norms (programs of action). Historically, the more meaningful the appropriation process became, the more meaning humans discovered in nature. But while the uncertainty of nature slowly decreased, cultural uncertainty just as slowly increased.

Knowledge or causal models of events and phenomena are not the exclusive prerogative of humans. The presence of elementary reason (i.e. understanding) in animals is demonstrated by their capacity to comprehend the simplest empirical laws of the environment, which enables them to develop programs of action for new situations. This is the difference between reason or intellect and any form of practice based on repetition or learning (Krushinsky 1986, p. 27). Animals have a mental representation of causality and the foundations of goal-directed behavior:

“When Pavlov began studying the behavior of great apes in his laboratory in the last years of his life, he was already talking quite definitely about a special type of association that can be considered concrete thinking: ‘And when an ape builds his tower to get a fruit, then you cannot call it a ‘conditioned reflex.’ This is a case of knowledge formation, of capturing the normal connection of things. This is a different case. Here it must be said that this is the beginning of knowledge, of understanding a constant connection between things—what underlies all scientific activity, the laws of causality’” (Krushinsky 1986, p. 10).

Human causal models are universal and allow the construction of action programs that are applicable to all situations encountered by a culture-society. In this respect, humans differ from animals, which construct empirical models that are only valid for a specific situation and create probabilistic rather than deterministic action programs (Krushinsky 1986, p. 11).

Knowledge is usually defined as “justified true belief.” However, knowledge cannot be reduced to belief without action. Belief is only justified if it enables action.

“Man is in a position to act because he has the ability to discover causal relations which determine change and becoming in the universe. Acting requires and presupposes the category of causality. Only a man who sees the world in the light of causality is fitted to act. In this sense we may say that causality is a category of action. The category means and ends presupposes the category cause and effect” (Mises 1996, p. 22).

As a cause-effect model or pattern of events, knowledge also implies a set of skills, that is, an action program.

Populations under mixed selection

The evolution of proto-humanity was based on the self-reproduction of its populations. The ability to reproduce is a property of life, but a cell or an organism can only reproduce as a whole: selection cannot act within them. A population as a collection of organisms of one species in a relatively closed habitat is the actual sphere of action of natural selection: the self-reproduction of a population is not based on the reproduction of the whole, but on self-renewal, on the alternation of generations of individuals (Berg 1993, p. 251).

Early human populations remained at the mercy of natural selection, but with the accumulation of culture, the self-reproduction of populations changed its character: populations became cultures-societies that reproduced themselves not only through natural but also through cultural mechanisms—not only through the transmission of genes and the interaction of organisms with the habitat, but also through the transmission of meanings and interaction of humans with the domus. Natural selection was gradually supplemented and expanded by cultural selection. Modern man is the result of a mixture of natural and cultural selection, he represents the unity of genotype and meaning type.

During the millions of years of mixed selection, the evolution of practices went hand in hand with the evolution of organisms, ensuring the adaptation of proto-human populations to a changing natural and cultural milieu—to changes in climate and natural landscape, as well as to changes in the landscape of meanings. Mixed selection has left clear traces in the human body.

“…Culturally accumulating communicative repertoires put selective pressures on genes for communicating: they pushed down our larynx to widen our vocal range, drove axonal connections from our neocortex down deep into our spinal cords to improve the dexterity of our hands and tongues, whitened the sclera of our eyes to reveal our gaze direction to cue others, and endowed us with reliably developing cognitive skills for vocal mimicry and communicative cueing, like pointing and eye gaze” (Henrich 2016, p. 251).

The brain, as a central part of the nervous system, plays a key role in the metabolism of primates and especially humans, in whom the second signaling system is built upon the first. A larger brain was crucial for the accumulation of culture. The modern human brain consumes 20 to 25 percent of an organisms’ metabolic energy, as opposed to 8 to 10 percent in other primates and only 3 to 5 percent in other mammals. To increase brain mass, it was necessary to reduce the mass of other metabolically expensive tissues—primarily the digestive organs—which was achieved by changing the diet (Smil 2017, p. 23).

Lighting a fire and cooking on it are not instinctive animal actions; they are practices passed down from generation to generation through learning. And these practices, which largely moved the digestion process outside the human body, greatly influenced the way our jaws and digestive system are constructed. Henrich writes (2016, pp. 65-69), referring to the work of Richard Wrangham, that mastery of fire radically reduced the energy used to function the digestive organs, which in turn affected the structure of the nervous system and the volume of the human brain, which was a prerequisite for the further accumulation of meanings. James Scott says, that mastery of fire not only led to changes in the human body, but also allowed man to greatly expand his ecological niche. Humans used fire to modify natural landscapes, thus creating conditions for the reproduction of animals and plants of interest to them. Over time, this led to a concentration of favorable flora and fauna, the emergence of more abundant and predictable food sources within walking distance of human dwellings, and subsequently to sedentarization and domestication (Scott 2017, pp. 58-60).

Mixed natural and cultural selection brought about genetic and meaning changes, shaped the biocultural traits of proto-humans, strengthened some of their aspects and weakened others, resulting in psychophysiological, moral-volitional and cognitive distortions in proto-humans. In short, mixed selection shaped human propensities. The new propensities in turn influenced subsequent selection, which in turn strengthened these propensities. Thus, human domestication gradually took place. Long before humans began to selectively breed animals, they began to culturally select themselves. As Matt Ridley says, humans are self-domesticated apes (Ridley 2003, p. 348).

“… Man of his own accord mediates, regulates, and controls the material reactions between himself and Nature. He opposes himself to Nature as one of her own forces, setting in motion arms and legs, head and hands, the natural forces of his body, in order to appropriate Nature’s productions in a form adapted to his own wants. By thus acting on the external world and changing it, he at the same time changes his own nature. He develops his slumbering powers and compels them to act in obedience to his sway” (Marx and Engels 1975-2004, vol. 35, p. 187, translation corrected).

As a result of millions of years of mixed selection, meanings are inscribed in nature itself, in human genes. With the emergence of culture, it begins to influence nature by creating a cultural environment (domus) within the natural environment and domesticating proto-humans to slowly transform them into the modern type of Homo sapience. “In the dialectic between nature and the socially constructed world the human organism itself is transformed. In this same dialectic man produces reality and thereby produces himself” (Berger and Luckmann 1991, p. 204).

Evolution of learning

The transmission of meanings between people, that is, learning, is based on imitation or mimesis, not on copying. Imitators do not have access to the content of the meanings they must acquire and cannot copy it. Therefore, the learning of meanings relies on active communication with other people, on the acquisition of norms through their expression. From norms, the imitators gradually arrive at the content, that is, understanding. In this way, imitators penetrate new cultural areas and learn meanings that were previously inaccessible to their understanding.