Полная версия

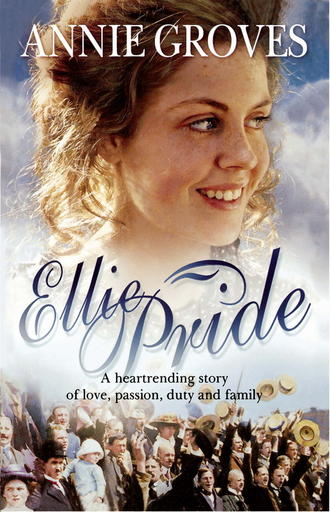

Ellie Pride

Lydia bowed her head, unable to make any response. How could she possibly tell her sister that she had been the one to urge Robert on?

A dull smog from the factory chimneys was thickening the air when Ellie and her mother finally left Winckley Square.

Ellie had noticed a tremendous difference in her mother these last few months. She no longer smiled and sang about the house, but had become critical and cross. Ellie couldn’t remember the last time she had seen her father come into the parlour and pick her mother up off her feet, as he had once frequently done, whirling her round in his arms and planting a kiss on her lips, whilst Lydia mock-scolded him for his boisterousness.

Yes, there was a very different atmosphere in the Pride household now, and although Ellie, growing quickly to womanhood herself, longed to know if in some way the baby her mother was carrying was responsible for the change in her, she knew better than to ask such an intimate question.

Ellie wasn’t ignorant of the way in which a child was conceived; their father’s family, for one thing, had a much more vigorous and salty approach to life than her mother’s, especially their Uncle William, the drover for whom Gideon sometimes worked.

William Pride was the black sheep of the family; a rebel in many ways, who had still managed to do very well by himself materially. And in doing so he also ensured that their father was supplied with the best-quality meat on offer, since it was William who went to the northern markets to buy fat lambs and beasts, as well as poultry in season, driving the animals back from the Lakes and Dales markets to sell to several butchers, including his brother.

Ellie knew that her mother did not approve of her husband’s brother, and she always tried to discourage her husband from spending any more time than necessary with him when he was in town.

As they hurried through the smog-soured streets, keeping their scarves across their faces to protect themselves from its evil smell, out of the corner of her eye, Ellie saw a group of young millworkers huddled in a small entry that led into one of the town’s ‘yards’.

The houses, crammed into these places to accommodate the needs of the millworkers at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, before the mill owners themselves had put up new terraces of cottages to house their workers, had no proper sanitation and were deemed to be the worst of the town’s slums. Even through the thick choking smog, Ellie had to wrinkle her nose against their nauseating smell.

A man crossed the street in front of Ellie and her mother, causing them to step into the gutter to avoid him as he stood in front of the girls, leering at them. Drunk and unkempt, he made Ellie shudder in distaste. Her mother tugged sharply on her arm, drawing her firmly away. But Ellie already knew that the place they had just passed was one of the town’s most notorious whorehouses.

Grimly, Mary Isherwood studied the dark and dank hallway of her childhood home in Winckley Square. Despite his wealth her father had been a notoriously mean man. Fires were only to be lit when he himself was at home, and her mother, the poor thin-blooded woman he had married when he was in his fortieth year, had shivered ceaselessly from November until April, her hands red and blue with cold.

Mercifully, Mary had inherited her father’s sturdier physique. It had been common knowledge that her father had only married her mother because of her connection with the landed gentry – and that having done so he had mercilessly bullied her and blamed her for the fact that she had not given him a son.

Mary had grown up hating her father even more than she had despised her mother. Naturally scholastic, she had infuriated her father with her ability to out-argue him, shrugging aside his taunts that she was too clever for her own good and that no man would ever want to marry her unless he himself paid him to do so.

She had never let him see how much that jibe had hurt her, but she had made sure that he paid for it. Only through her could he have grandsons, the male heirs he longed for, and she had decided that he would never have them. She would never marry; never put herself in a position where he could boast and torment her that he had bought her a husband. Mary was every bit as stubborn as her father had been, and she had stuck to her resolution.

It had shocked her to learn that he was dead, and it had shocked her even more to discover that she was his sole heir. She had expected that he would cut her out of his will – that he would rather leave his wealth to the foundling home, whose occupants he so brutally used and destroyed working in his appalling factories, rather than allow her to see a penny of it.

The factories were sold now. Horrocks’s had made her father an offer he couldn’t refuse, and Mary was glad of it. They represented everything she most hated.

Perhaps her father would have redrafted his will if he had realised that he was facing death. Mary felt ironically amused to learn that he had died of a chill on the lungs. Her mother had suffered a long agonising decline and a painful death from tuberculosis, brought on, Mary was sure, by her husband’s refusal to allow her any home comforts. She had lived as poorly as any of the workers in her husband’s mill.

Yes, Mary reflected, her father had been a hard man and a cruel one, but now he was dead, and she had decided to move back to Preston. She knew people would question her decision, but she had her own reasons for being here.

Frowning, she studied the huge oil painting of her father that hung at the top of the stairs.

‘I want you to take that down,’ she instructed the removal men.

‘That’s fine, missus, but where will you be wanting us to put it?’ the foreman asked her.

‘Anywhere you like, just so long as it is gone from this house,’ Mary responded coolly.

She had ordered coal to be delivered ahead of her arrival, but it seemed that her late father’s housekeeper had not received her instructions to light fires in every room. Ringing for her, Mary stood in the hallway and watched as the men struggled with the huge gilded frame.

She had been eighteen years old when the portrait had been commissioned and her father had been at the height of his power. He had paid the man who had painted it more than he had spent in feeding and clothing her mother and herself in a dozen years. Mary knew because she had seen the bill.

‘You rang for me, miss? Oh, the master’s portrait…’ The housekeeper, Mrs Jenkins, placed her hand to her throat in shock as she saw what the men were doing.

‘Yes I did,’ Mary confirmed. ‘It seems that a letter I sent you from London, requesting that you have fires lit in all the rooms, went astray. And –’

‘Oh no, I got the letter, miss,’ Mrs Jenkins confirmed, ‘but the master would never have allowed anything like that. Why, even in the week he died he refused to have a fire lit in his bedroom, despite the doctor saying that he should.’

Mary could tell from her accent that the housekeeper was a countrywoman, and she suspected that, like everyone else who had ever worked for her father, she had been in terror of him.

‘My father is dead now, Mrs Jenkins, and I am mistress here,’ Mary replied. ‘You will, I hope, find me a good and a fair mistress, just so long as you understand that it is I and not my father who now gives the orders. As soon as you have a maid free you will instruct her to light all the fires, please.’

‘Very well, miss…but you cannot mean to remove your father’s portrait,’ the housekeeper blurted out. ‘He was that proud of it; used to stand and look at it every day, he did, before he got poorly.’

‘Thank you, Mrs Jenkins, I am aware of my father’s pride in himself.’ And of every other aspect of his unpleasant personality, Mary could have added.

She still bore the faint scars on her back where he had whipped her as a child. She was forty now, but sometimes at night, when she couldn’t sleep, they still ached.

‘But what is to go in its place?’ the housekeeper was fretting. ‘The wallpaper will have faded, and in such a large space –’

‘If it has then we shall have new wallpaper, Mrs Jenkins. In fact, I believe we shall have new wallpaper anyway. Something light and modern. Now just as soon as the men have finished, I want someone to take them down to the kitchen and give them a good hearty meal before they leave.’

The housekeeper was staring at her, and Mary guessed why. She doubted that anyone in the household knew what a good hearty meal was. Well, they were soon going to discover.

She might have particular plans for the huge inheritance she had received, but that did not mean that she didn’t fully intend to enjoy some of its benefits immediately. Starting with doing something about the house.

As the men brought the painting down the stairs, the artist’s name glittered under the light of the chandelier. Hesitantly, Mary reached out and touched it, running her fingertips over the slightly raised surface of the paint.

Richard Warrender.

Very briefly she closed her eyes. Some memories were too painful for her to recall, even now.

FOUR

‘A puppy for John, is it, or more like a sweetener to win the favour of young Ellie?’ William Pride laughed as he watched his young helper button the collie pup he had brought with him from the borders inside his jacket.

‘You’re wasting your time there, my lad,’ William told Gideon, shaking his head. ‘She’s a fine-looking girl, I’ll grant you that. Got her mother’s looks and her fancy airs and graces as well. Lyddy will never allow any daughter of hers to get sweet on a working lad like you. Thinks too much of herself for that, she does.’

‘Mr Pride has always made me very welcome in his home,’ Gideon said stiffly.

‘Oh aye, our Robert – Mr Pride – he will, but we’re talking about Mrs Pride now, lad, ’er as was “a Barclay” before she wed our Robert. I remember how it was when they first met. Let us know that she thought herself well above us, she did, allus talking about her father the solicitor in that posh voice of hers. Of course, our Robert was well fixated on her. Daft as a tuppence-halfpenny wristwatch he was – dafter! I could never see the sense in it m’sel’. Never catch me allowing any woman to rule my life. Good enough in their right place, women is, but only that place!’ He winked meaningfully at Gideon. ‘What tha’ wants, lad, is some willing wench – but make sure she’s clean, mind. I don’t mind telling you I had my problems in that way when I was a young green ’un. Don’t you make the mistake of settling for one before you’ve sampled a few like I did, either. Naught wrong with our Gertie, mind, but a bit of choice isn’t a bad thing, if you know what I mean.’ He grinned, tapping the side of his nose.

Grimly, Gideon forced himself not to object. He knew exactly what his employer meant, and he knew too that once they had parted company William would make his way first to the pub, where he would garner the current gossip, and then to the home of the woman who was his ‘wife’ whenever he was in the town, and by whom he had three tow-headed sons.

Gideon wasn’t finding it as easy to get work as he had hoped – but William Pride paid a fair wage to his men, even though the work itself wasn’t what Gideon really wanted to do.

Every time they visited Preston, as well as calling at Friargate, ostensibly to update John on the progress of his pup, Gideon combed the town’s streets, looking for somewhere to set up his business.

So far his search had been disappointing. Those townspeople rich enough to employ a cabinet-maker, instead of buying ready-manufactured furniture, automatically looked to tradesmen they knew and believed they could trust, many often going as far afield as Gideon’s own ex-master in Lancaster.

He had had one small but potentially lucrative job, which had set his hopes soaring – the restoration of a carved banister in a tumbling-down manor house in Lancashire, which had been bought by a newly rich railway shareholder, but the man had refused to pay Gideon the full amount they had agreed, and he had been lucky to cover his costs for the job, never mind make a profit.

He was not about to give up, though. The struggle he was having now would make his eventual success very sweet, and even sweeter if he were able to have Ellie to share it with him.

Ellie. How she teased and tantalised him, giving him bold, tormenting looks one minute, and the next blushing a softly delicious pink just because he had happened to comment on her mother’s pregnancy.

Gideon frowned as he thought about Lydia Pride. There was a very different atmosphere in the Pride household now, in April, than there had been when he had first been invited there in Guild Week.

Robert Pride himself had changed, Gideon believed. He no longer seemed to laugh as easily or as heartily, and there was a hangdog, sheepish look about him whenever he was around his wife.

Even Ellie seemed to be affected by the change in her parents’ relationship, and Gideon had seen how very protective she had become of her mother.

The pup inside his jacket struggled and yelped, reminding him of its presence and his plans. He had first to take his bag to his lodgings – a small but reasonably clean room tucked away at the back of a small courtyard – and then he would deliver the puppy – and set eyes again on Ellie.

‘Show me again, Gideon,’ John pleaded as the balls he had been trying to juggle refused to move as dextrously in his hands as they did in Gideon’s.

Laughing, Gideon did so. They were standing outside Robert’s shop in the sharp spring sunlight, waiting for the rest of the Pride family. Robert had invited Gideon to join them for the traditional Easter Monday egg rolling in Avenham Park, and Gideon had accepted gratefully, only too pleased to have a legitimate excuse to spend some time with Ellie.

‘If you don’t want to go to the park, Mother, would you like me to stay here with you?’ Ellie offered anxiously.

‘No, you must go, Ellie, if only to keep an eye on John and that wretched dog of his,’ Lydia sighed tiredly.

The combination of a boldly inquisitive and danger-prone ten-year-old and an equally adventurous collie pup was not one that was designed to soothe a mother’s natural fears.

John had become devoted to his pet. They went everywhere together, and virtually every day he insisted that they all watch whilst this wondrous creature performed some new trick he had taught it.

‘And look out for Connie too. You know what she’s like.’

The closer it got to her due date, the more haunted Lydia was becoming by the warnings she had been given. It was all very well for Robert to say that doctors always tended to look on the black side, and to remind her that she had already produced three healthy children with no risk to herself whatsoever. Sometimes in the night she dreamed that she was a girl again, her body slender and empty, and she would wake up full of relief until she realised the truth.

Her sisters, she knew, blamed Robert, and so increasingly did she.

As the youngest child of the family she had perhaps been indulged rather more than the others – she had certainly been far more rebellious. Also her marriage, Lydia knew, was different from those of her sisters, just as her nature was different. If her daughters had inherited that streak of sensuality from her they would need to learn to guard against it, otherwise…

‘Are you sure?’ she heard Ellie asking her.

‘Yes. You go, and, Ellie…’ But as Ellie turned back, Lydia shook her head. ‘It doesn’t matter.’

To warn her daughter at this stage against Gideon Walker might do more harm than good. Ellie was a young girl, after all, and Gideon was an extremely handsome young man. Lydia was not so old that she could not remember the way she had felt when Robert had first looked at her with his bold, laughing eyes and his warm smile…

Sunshine danced on the crystal bowl in the middle of the table, and suddenly Ellie was impatient to be outside. Giving her mother a swift kiss, she hurried to the door.

‘John, if you are not careful you will break all your eggs before we even reach the park,’ Ellie scolded, as John, growing bored with his family’s leisurely progression, began to swing his basket of eggs.

The town’s Easter Monday festivities at Avenham Park was a popular and well-attended event, especially the egg-rolling race.

But much as John wanted to hurry them towards what he considered to be the most important and exciting part of the day, his sisters obstinately refused to listen.

‘Oh, Ellie, do look. There is Sukey Jefferies from school. Just look at her dress.’ Connie was tugging on Ellie’s arm.

Judiciously Ellie studied the other girl, who, like them, was accompanied by her family. The Jefferies family were involved in the cotton trade, and considered to be well-to-do, even though they did not actually own any of the town’s mills.

‘The silk is far too rich for a daytime outing,’ she pronounced, ‘and as for all those lace frills and flounces…’

‘It looks very grand,’ Connie breathed enviously. ‘I wish that Mother would allow me to wear a proper grown-up dress, instead of making me wear these stupid pinafores, like a child. After all, Sukey is only a year older than me.’

‘She is two years older,’ Ellie corrected her, ‘and her dress is far too fussy.’

It wasn’t just their beauty that the Barclay sisters were renowned for, it was their taste and stylishness as well, and Ellie knew instinctively just what her mother would have thought of Sukey’s gown, with all its fanciful, overdone trimmings.

Her own dress, for all its simplicity, was, Ellie knew, far more stylish and elegant, but before she could say as much to her sister, John was rudely interrupting their conversation, demanding, ‘Oh, why must we waste time talking about such stuff? If we don’t hurry we won’t get a decent place.’

‘There is plenty of time, and I know the exact spot we need,’ Ellie reassured him, unaware that she was being observed keenly by Gideon, walking slightly behind them with her father, as she gave John an impishly droll look.

‘What, you mean you will show me the spot you’ve won the egg race from three years running?’ John exclaimed in excitement.

This awesome feat by his elder sister had become a part of their family history, and secretly it was John’s goal not just to match it but, with luck, to better it.

‘What’s this? I hadn’t realised that we had a champion egg roller in our midst!’ Gideon exclaimed, joining in the fun.

Flushing a little, Ellie nevertheless held his gaze.

‘I think we shall have to put your skills to the test,’ Gideon announced, ‘since I consider myself to have some sporting skill.’

‘Yes! Yes!’ John encouraged, dancing up and down.

‘What do you say, Miss Pride – will you allow me to challenge you?’ Gideon laughed.

A little uncertainly, Ellie looked at her father, half expecting and even half hoping that he might object and insist, as she suspected her mother would have done, that such behaviour on her part would be unseemly, but to her consternation he just laughed and said, ‘You will have to be very good, Gideon, if you are to best Ellie. Had she been a boy I dare say she would be captaining the Hutton cricket team by now.’

They had nearly reached the end of the elegant colonnaded walk that led into the park. Several family groups had paused to chat, and Ellie recognised her cousin Cecily in one of them, with her fiancé, but she didn’t draw her father’s attention to their presence, sensitively aware that Cecily might not want to acknowledge them if she was with her fiancé’s family.

Cecily’s father-in-law-to-be was, as Aunt Gibson had proudly informed her sister, a very senior Liverpool surgeon, Sir James Charteris, who, through his wife’s family, was connected with the nobility!

A group of girls of around her own age hurried past them, and Ellie guessed from their loud voices that they must work in one of the town’s mills. Everyone knew that the noise inside the weaving sheds turned people deaf and that the millworkers had devised their own sign language for communicating with one another.

One of the girls suddenly stopped. Taller than Ellie, with a wild mane of thick curly red hair and a pale complexion, she gave Ellie an astutely assessing female look before tossing her head dismissively and going boldly up to Gideon, throwing him a look that was openly flirtatious, as she exclaimed in the thickest of the town’s dialect, ‘Well, if it isn’t Mr Gideon Walker…’

‘Good afternoon, Miss Nancy,’ Gideon responded with an easy openness that shocked and dismayed Ellie. Immediately she drew herself up to her own full height and pursed her lips every bit as disapprovingly as her mother would have done.

‘Miss Nancy!’ the redhead emphasised, and laughed.

‘Come on, Nance.’ One of the other girls tugged on her skirt. ‘There’s free refreshments for them as gets there first, and I’m fair clemmed…’

Watching the girls hurry away, Ellie had to admit that the cheap dress worn by ‘Miss Nancy’ had far more style about it than those of her companions. Did Gideon find the redheaded mill girl attractive? Did he think her pretty…prettier than she? Did he want to kiss her? Had he perhaps already kissed her?

Ellie’s mother considered that red was not a suitable hair colour for a young lady, and Ellie had been brought up to be proud of her own soft golden curls, but now suddenly she was sharply aware that a woman did not necessarily have to have blonde curls and ladylike manners to attract a man.

‘Who was that?’ John demanded, too young to feel any need to conceal his curiosity.

‘Miss Nancy and some of her co-workers rent rooms in the house next to where I rent my own,’ Gideon explained easily. ‘She came to me for assistance some time ago, when…when one of the girls had…had fainted. I believe that underneath her brash manner she is a good sort, and –’

‘These mill girls have a very hard life,’ Robert Pride interrupted. ‘Every year so many are killed in accidents with the heavy looms. There is much talk of the need to reform the conditions under which the mills are run.’

‘There is always talk,’ Gideon replied sharply, ‘but very rarely any action, and even when there is, the mill owners seem to find a way to circumvent it. I was called into one of the mills the other day to repair a piece of machinery – I think I would go mad had I to work there permanently. The noise alone, never mind anything else.’

Ellie could feel the heaviness that had enveloped the two men as they talked. The looks on their faces reminded her of the man she had seen in the fish market the previous Friday when she had gone there with her mother.

He had gathered a small crowd around him, and Ellie had been forced to wait until a pathway had been cleared before she could follow her mother past him. Whilst she had done so, she had heard the man declare, ‘These mills are a running sore on the face of our town, and worse, the running sore we can see. But what of those other sores which are hidden shamefully from view, the plight of those who work in such abominations? The plight of our womenfolk, our sisters, our daughters, our mothers…’

Ellie’s mother had dragged her away before Ellie could hear any more.

Now suddenly she felt angry with ‘Miss Nancy’ for intruding on the happiness of her day.

‘Come on,’ John was urging them all. ‘Hurry up…’

‘Are you sure you haven’t changed your mind?’ Gideon demanded teasingly as he and Ellie stood side by side at the top of the hill.

All around them children were rolling their eggs, their cries of disappointment or triumph filling the air.

Since neither she nor Gideon had come equipped with eggs to roll, Gideon and her father had purchased some from one of the booths set up in the park. Surreptitiously Ellie checked them. In her experience the right consistency of hard-boiled egg was essential if they were to roll any distance – and not just the consistency of the inside of the egg. She had always painted hers with a special paint she had mixed herself, which had helped to bond the shell together. But these eggs…