Полная версия

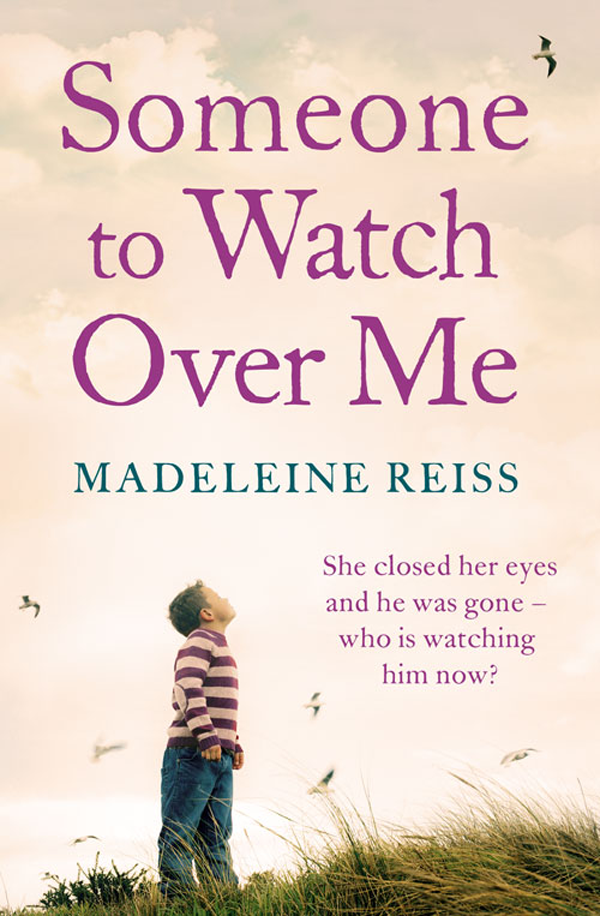

Someone to Watch Over Me: A gripping psychological thriller

MADELEINE REISS

Someone to Watch Over Me

To my dearest three – David, Felix and Jack And in love and memory of my father, Barry Unsworth 1930–2012

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three

Chapter Fifty-four

Chapter Fifty-five

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Q&A with Madeleine Reiss

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

He held her hand tightly. It was dark and it was hard to see the path. She had told him to watch where he put his feet and not to get too near the black channel of water. He knew for a fact there were bad things hidden right down deep at the bottom of it. There were supermarket trolleys and stolen cars and rotting cows, which had toppled out of their fields into the canal and not been able to get out. There were snakes that swam all twisty through the coldness. He thought that there were people in there too. He thought of bodies floating upright, anchored to the slimy bottom by curling fronds of weed. He had once seen an eyeball coming out of a drowned person’s head on a TV programme. He had watched through the crack in the door and afterwards he had wished he hadn’t. Once you saw things they stayed with you forever. Even though they were walking so fast it made him breathless and even though her nails were digging into his hand, he was glad to get out of the house. He just wished he knew where they were going.

‘Will we be able to stop soon?’ he asked.

‘Just a bit further. We can’t stop yet.’

Her face gleamed all white and her mouth was stretched out thin. He knew they would never be able to go fast enough or far enough, however hard they tried. He wished they could change themselves into giant birds and fly as far as Africa. Big, yellow birds that could see in the dark and camouflage themselves against the sand in the daytime. In his brain he sang the song that made him feel better and tried with all his might to escape into clear open spaces and a sea without edges.

Chapter One

Carrie stood on the pavement outside the shop. It looked even better than she had imagined it would. The window, trimmed with lace stencils and silver stars, framed a display of what she hoped were the most irresistible Christmas gifts ever. There were creamy cashmere dressing gowns, strings of crystal beads, amber earrings with ancient insects trapped in their glowing depths, vintage cake stands laden with glittering brooches, elegant party shoes with buckles and curved heels, old silk scarves traced with faded Eiffel Towers and caped matadors. Tomorrow, Trove would open its doors to the paying public, and all the months of work would have been worthwhile.

Back inside the shop she checked that everything was perfect; the pan of mulled wine was ready to be heated up on the tiny stove in the back room, the cinnamon-scented candles were lined up along the counter alongside the piles of brown bags, each stamped with the name of the shop and fastened with red ribbon. She took one last look round, then set the alarm and clicked off the lights. Her bike was locked up at the back of the shop, the saddle already sheened with frost. Tucking her coat around her legs and sitting gingerly on the hastily wiped seat, she set off down the road hoping that her flickering front light would last until she got home. She had bought the bike from a shop just round the corner from where she lived and she had realised, even as she was buying it, that it wasn’t the most practical of purchases. She should have looked more closely at the state of the tyres and at the chain clotted with rust rather than been seduced by its green and silver stripes and large wicker basket laced through with plastic daisies.

As she cycled down the largely empty streets, she looked into windows warmed with lights and decorations and clouded with cooking steam and the moisture from people talking and laughing in small rooms. Carrie felt the familiar sadness settle around her heart. She could distract herself for some of the time, but it always came back to this. This dogged pain that refused to let her go, but carried her mercilessly out to that wide-open sea and sky.

It had been Carrie’s decision to go to the coast that day; Damian would have preferred to have stayed at home to read the papers and fix the fence that had blown loose sometime over the winter. She loved expeditions, particularly those that involved chill bags and flasks, and she got up early to fix a feast of cheese and tomato baguettes and crisps and some sinful sundae-type desserts in their own plastic glasses. Charlie, who had just turned five, hadn’t yet mastered the sandwich. Cheese was fine, and bread, by itself, was more than acceptable, but put the two elements together and he acted as if she was offering him something impossible to contemplate, a culinary monstrosity that made his small shoulders shudder. For Charlie she packed a hunk of bread, some Babybel cheeses and a cake with pink icing.

It was the sort of summer day that is called perfect because it is so very rare. They rolled down the windows as they drove, and the car seemed to be full of sun and the smell of warm plastic from the water bottles on the back seat. The Norfolk coast was only a couple of hours away from Cambridge, an easy drive on a chilly day, but likely to be slower today with the roads full of people making for the sea. Charlie had developed a taste for Ella Fitzgerald and sang along under his breath to the CD he insisted on having at full volume.

‘“I love to go out fishing, in a river or a creek, but I don’t enjoy it half as much as dancing cheek to cheek …” What’s a creek?’

‘A stream, as in, “I’m up shit creek without a paddle”,’ said Damian, who was better than Carrie at providing succinct explanations of the meaning of words.

‘Umm … Dad said a rude word!’ said Charlie with delight.

Carrie could see her son in the wing mirror. She loved looking at him. At his neat head, his serious dark brown eyes, the way his eyebrows rose and rounded every time he talked. Sometimes she went into his room and watched him sleeping, even climbed the first rung of the ladder of his bunk bed so that she could get close enough to smell that combination of salt and sweetness that was unique to him. She wasn’t a particularly patient mother. She wasn’t fond of activities involving flour or tubs of poster paint and there were times when his chatter drove her to a kind of bored distraction, but most of the time he dazzled her. Her love felt overwhelming, liquid, like blood through veins or a sea, filled beaker-like to the very brim.

They arrived at the beach at about lunchtime and dragged food and rugs and buckets along the sand until they found a place that was far enough away from other people to satisfy Damian, who had a ‘no radios, no dogs and no other people’s children’ rule which tended to narrow their options. Since having Charlie, Carrie also had a rule which she kept to herself that involved not setting up camp anywhere near young, firm girls who looked as if they might strip off at any moment and indulge in a vigorous game of volleyball. They settled at last for a hollow in the dunes, some distance away from a woman and a boy about the same age as Charlie, who were lying on their backs on striped beach towels. Carrie anchored the water bottle in the shade of the grass, which fringed the dip in the dune like eyelashes, and unpacked the swimming costumes. Then they took off their sand-laden shoes and walked to the sea. A day at the beach always began for them with this small act of homage.

The tide was coming in slowly and the sun glittered in patches where the water had gathered. The ridges of moist sand were so firm beneath their bare, car-softened feet that it was almost painful to walk. Charlie squatted down to examine the intricate piles of wormed sand and to hook up fragments of mussel shell with pruned fingers. His yellow shorts were too large round his waist, despite Carrie having sewn up an inch on either side, and when he ran he gathered them up with one hand to prevent them falling down. The perfectly blue sky stretched away, until it imperceptibly merged with the sea at a point so distant that it was impossible to see where sea ended and sky began. It felt as if you were walking in a thin membrane stretched to infinity. Although the day was warm, after a couple of weeks of overcast weather, the warmth hadn’t yet found its way into the sea.

‘Can I go swimming?’ asked Charlie, oblivious to the temperature. He threw himself forward in the shallows, kicking vigorously, churning up the sand, trying to tempt them in by pulling at their ankles. He was beginning to learn to swim, but still needed his inflatable wings. Carrie and Damian kept walking and Charlie splashed alongside them. It seemed as if the water would never get deeper and that the three of them would move forward forever. Hunger finally made them turn back to the beach. That, and the fact that Charlie’s lips were turning blue. Damian lifted his son up and wrapped him in his shirt.

When they turned round and headed back for their spot in the dunes, they saw a flamingo standing in the water between them and the beach. Carrie thought at first it was a blow-up toy, too impossibly bright to be real. Its exotic shape and colour out of place in the pale, bleached landscape. But then it bent its neck and dipped its head repeatedly in the water.

‘It must have escaped from a bird sanctuary,’ said Damian.

The bird shook itself, as if, like them, it had expected a warmer ocean, took a clumsy run forward and then lifted off with a curious sideways movement, head and neck stretched out, its legs trailing behind like an afterthought. They watched it fly away until it was just a speck.

‘Will it come back, Mum?’

Charlie asked her the question because he knew the beginning of a story when he saw one, and indeed, Carrie was already thinking about a possible bedtime tale which could feature a confused flamingo called Fabian and perhaps Florette, a lost flamingo wife.

‘Why is it pink?’

Damian knew it was something to do with its diet, but was unable to say what it could find on a Norfolk beach that would be pink enough to maintain its plumage.

‘Will it go grey after a while?’ asked Charlie anxiously.

‘I’m not sure, pal,’ said Damian. ‘Perhaps he will find his way home where his brothers and sisters and a bucket of fresh shrimps will be waiting for him.’

After he had been persuaded into a fleece, they had lunch. Charlie ate his bread and an apple and said he wanted to save his cake for later. He sat for a while, watching the boy whose encampment was nearest theirs. He was squatting on his heels and digging energetically. Carrie could tell that Charlie wanted to play with him by the way that he kept sliding his small feet through the sand.

‘Why don’t you go and make friends?’

‘I think he’s older than me,’ said Charlie. She knew how much he hated to be at a disadvantage.

‘He looks pretty much the same age to me.’

Charlie got to his feet and wandered in a self-consciously casual way over to where the boy was scooping up sand. For a while Charlie pretended to be looking for shells, but then he gave up dissembling and stood over the other boy, watching his endeavours with a critical eye.

After what he clearly considered to be the correct amount of time, Charlie finally spoke.

‘My name’s Charlie. I’m five. How old are you?’

The boy looked up at him and answered. Carrie didn’t catch what he said, but it must have been encouraging because Charlie got down on his hands and knees and started burrowing too. They each began to excavate from a different point and dug along towards each other. Whenever their hands made contact under the cool sand and another tunnel was formed, they exclaimed in surprise. Carrie watched them for a while, but then the effects of lunch and the sun began to catch up with her and she lay back on the picnic rug. She could hear Damian turning the pages of the newspaper, the occasional voice shouting, and once, what sounded like a helicopter, but the sounds were muffled. Black shapes swarmed behind her eyelids and she dozed. She woke when Damian tickled her bare feet.

‘Sorry to disturb you, sleepy head,’ he said, ‘but I need to go to the toilet. I’ll have to go back to the car park.’

Carrie shook herself awake and sat up to look at Charlie, who was still playing with his new friend. She got her magazine out of her bag, rolled over onto her stomach and tried to read but the words swam in front of her eyes and she laid her head down on the paper and slid back into sleep. Charlie’s voice woke her the second time. She rolled over onto her side and squinted up at him, but the sun was too bright to see his face.

‘Can I go down to the sea again?’

‘Only if you go with your father.’

‘Dad’s still not come back.’

‘Well you’ll just have to wait until he does. Where’s that other little boy gone?’

‘He had to go for a walk with his mum.’

‘Is he nice?’

‘Yes.’ Charlie made his case by ticking off his new friend’s attributes on his fingers.

‘One, he is five. Two, he has yellow hair. Three, he isn’t mad on bats. Four, he likes Scooby Doo. Please can I go down to the sea?’

‘Just wait a bit, I can’t leave the bags. Wait till Dad gets back.’

Carrie sat up, and Charlie sat down next to her, looking up every now and again to see if Damian was coming. Finally he spotted him in the distance making his way back down the beach.

‘Can I go and meet him … please … and then we can swim …?’

‘Only if you give me a kiss first,’ said Carrie, lying back down. He knelt next to her and planted his lips on her cheek, stroked one sandy hand across her face.

‘I love you every single day,’ said Charlie.

‘And I love you every single day too,’ said Carrie, and shut her eyes.

Afterwards, she wasn’t able to say how long she had been asleep. She thought it could only have been a matter of minutes.

‘Where’s Charlie?’ asked Damian, appearing suddenly above her.

Carrie, like every parent, was always only a moment away from panic. All it took was for her to lose sight of him when he lagged behind in a crowd, or when he was hidden by a slide in a park, and she felt a dip in her stomach. She felt that familiar lurch now.

‘I thought he was with you.’

‘No, I left him here when I went to the toilet. I’ve just been for a run.’

Carrie stood up and scanned the beach. There were a number of figures in the distance that could have been him. It wasn’t easy to see that far away. She couldn’t immediately spot anyone in the distinctive yellow shorts he was wearing.

‘You stay here in case he comes back. I’ll go and look for him.’

Carrie started running towards the sea.

Chapter Two

Molly watched Max as he lay on the floor, lining up his plastic animals in strict formation. He was using the geometric design on the border of the carpet to ensure that all hooves and paws toed the line. The ark stood waiting with its gangplank down and its tiny bearded Noah standing to attention on the deck. Max’s tendency to place things in lines was sometimes disconcerting – miniature soldiers faced certain death as if about to start a race; crayons lay in an orderly rainbow all the way along the hall. Cards trimmed the mantelpiece in royal flushes. He even rearranged the food on his plate in sequence, with the least desirable items bringing up the rear. Since this was a recent habit, Molly wondered if this behaviour was a sign of inward disturbance. Possibly she should be worried by his seemingly compulsive need to order the world. Maybe she was simply reading too much into it and he was disclosing a propensity that had always been there, waiting for the right set of animals or the new box of crayons. He had probably been born with the straight-line gene, and would grow up into an adult who was fond of graphs and trousers ironed sideways and pint glasses placed neatly in the centre of beer mats. She thought that what she was really looking for in his behaviour, were confirmations of her own sadness.

Although the Christmas tree bent slightly to the left, Molly thought it looked pretty, with its multi-coloured lights flicking out some sort of puzzling rhythm. They had gone and got the tree together and brought it back in the car with its tip sticking out through the window. She had resisted the temptation to take charge of its decoration, despite the fact that Max had adorned all the lower branches with the heaviest baubles so that they bent at the ends and almost touched the floor.

She started to put away the canvas she had been working on earlier in the day, a small watercolour of the view out of the window. It was the first thing she had painted for a long time and it felt good to be getting back into doing even a little of what she loved. She looked out of the window, across a wide, black field over which birds gathered and then dispersed. It was beginning to get dark although it was still only three o’clock. She felt oppressed and anxious, as if this small house was cast adrift on floodwaters, without a compass or proper provisions. Molly was keen on the acquisition and preservation of provisions. As a child the stories she had loved the most always involved families in extremis eking out bitter winters with a small box of onions and turnips and fashioning pathetic, yet admirable playthings out of twigs and balls of wool. She liked fictional characters who bottled and salted their way through their lives and nobly stacked their larders with the labours of their presumably very rough, red hands or who, when left on desert islands, conjured up ingenious accommodation and cunning ways of collecting rain water. She had always celebrated each season by preserving it. Jam from the warm strawberries she had heaped into smeared punnets. Blackberries brought home in jugs and Tupperware boxes and then stashed away in freezer bags. Each sloe carefully pierced and pickled with gin and put in the dark to marinate.

‘When’s tea?’ asked Max, rolling onto his back, a rhino in each hand meeting horn to horn.

‘Not for ages yet,’ she said. ‘Are you hungry?’

‘Can I have just one chocolate bell from the tree?’ he said. ‘That should tide me over.’ She recognised with pain that this was one of Rupert’s expressions. She thought of him years ago, packing the boot of the car to go away somewhere with more food and drink than they could possibly need. ‘That should tide us over,’ he had said and smiled, and she remembered feeling the safety in the words.

Max untied a chocolate from the tree, careful to avoid touching the wire from the flashing lights. He had a morbid fascination with electrocution, and the slightest darkening of the skies would provoke dire warnings on the danger of standing under trees and wearing leather-soled shoes. It had been Rupert who had planted the horror in Max’s mind by telling him some outlandish tale of putting his finger into a socket and being thrown through a window and biting all the way through his tongue until he almost choked on his own blood.

He always was a convincing teller of tall tales. Molly thought about the evening they had first met. He had seemed more vivid and distinct than anyone else in the room. Her eyes had been drawn to him straight away and she had found it hard to stop looking. Rupert had reminded her of a fox, or some other shiny-furred creature. She had always thought of herself, with her pale blue eyes and hair of an indeterminate brown, to be the very reverse of striking. She had often despaired at the soft, almost child-like contours of her face, wanting instead to have high cheekbones and dark, dramatic lashes, the sort of looks that made men catch their breath, and so she’d been astonished when he came straight over to her, as if he had been waiting for her to arrive, although they had never met before.

‘You can sit by me,’ he had said, steering her over to the table and the chair next to his. He had talked to her throughout the meal, his eyes never leaving hers, his hands solicitous with butter and wine. When her napkin slid off her lap and fell under the table, he insisted on ducking down and retrieving it. She felt, with shock and excitement, his hand brush her ankle and pause delicately, halfway up her leg.

They were married six months later. She had set her heart on a dress that she had seen in a shop window. The material was the palest pink and encrusted with crystal beads. It had a tight bosom-enhancing bodice and fitted sexily across the hips and made Molly feel like a decadent princess. Molly thought that being a bride was your one chance to be voluptuous and get away with it. Rupert’s mother, whom she had only met once and whose eyes, on that occasion had shifted over her swiftly as though assessing a metre of fabric, had insisted both on paying for the dress and coming with Molly to choose it. She dismissed the frock Molly had selected with a small sound of distaste and chose instead a severely simple sheath. Although its pale lines were exquisitely cut and it was four times the price of the dress she had wanted, Molly never felt like herself in it – but rather as if she was playing the part of the person that should have been standing by Rupert in the little church that was filled with the scent of lilac.

They honeymooned in Umbria in a villa that looked out over terraced olive groves and a night sky full of fireflies. They spent their days exploring the nearby towns where Rupert took hundreds of pictures of her by fountains or leaning against yellow walls threaded with caper flowers and quick lizards. Sometimes when he stopped her halfway up some steps and made her turn towards his lens or when he laid down his fork to frame her head exactly beneath an arch she felt as if the sequence of pictures were what made the story for him.