полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 382, July 25, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 382, July 25, 1829

POPE'S TEMPLE, AT HAGLEY

Reader! are you going out of town "in search of the picturesque"—if so, bend your course to the classic, the consecrated ground of HAGLEY! think of LYTTLETON, POPE, SHENSTONE, and THOMSON, or refresh your memory from the "Spring" of the latter, as—

Courting the muse, thro' Hagley Park thou strayst.Thy British Tempe! There along the dale,With woods o'erhung, and shagg'd with mossy rocks,Whence on each hand the gushing waters play,And down the rough cascade white dashing fall,Or gleam in lengthen'd vista through the trees,You silent steal; or sit beneath the shadeOf solemn oaks, that tuft the swelling mountsThrown graceful round by Nature's careless hand,And pensive listen to the various voiceOf rural peace; the herds, the flocks, the birds,The hollow-whispering breeze, the 'plaint of rills,That, purling down amid the twisted rootsWhich creep around their dewy murmurs shakeOn the sooth'd ear.Such is the fervid language in which the Poet of the year invoked

"LYTTLETON, the friend!"Yet these lines will kindle the delight and reverence of every lover of Nature, in common with the effect of the Seasons on the reader, who "wonders that he never saw before what Thomson shows him, and that he never yet has felt what Thomson impresses."1

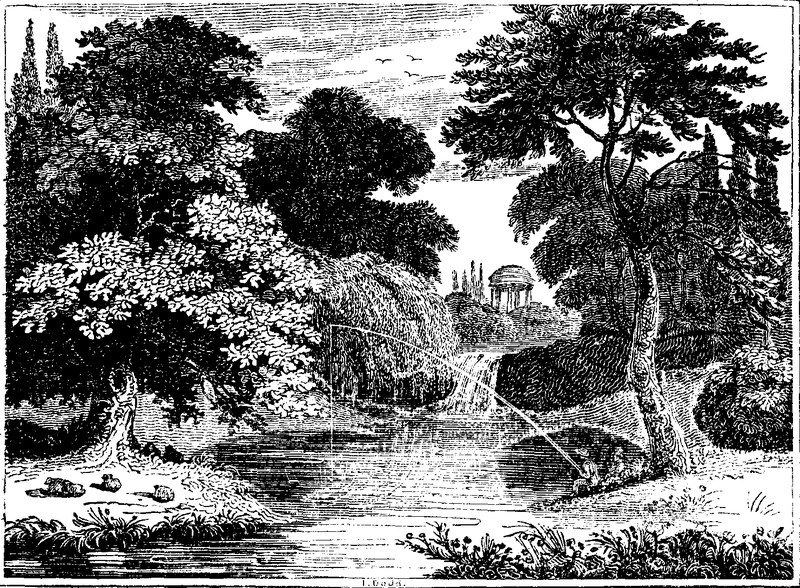

But we quit these nether flights of song to describe the locality of Hagley Park, of whose beauties our Engraving is but a mere vignette, and in comparison like holding a candle to the sun. The village of Hagley is a short distance from Bromsgrove, in Worcestershire, whence the pleasantest route to the park is to turn to the right on the Birmingham road, which cuts the grounds into two unequal parts. The house is a plain and even simple, yet classical edifice. Whately, in his work on Gardening, describes it as surrounded by a lawn, of fine uneven ground, and diversified with large clumps, little groups, and single trees; it is open in front, but covered on one side by the Witchbury hills; on the other side, and behind by the eminences in the park, which are high and steep, and all overspread with a lofty hanging wood. The lawn pressing to the front, or creeping up the slopes of three hills, and sometimes winding along glades into the depth of the wood, traces a beautiful outline to a sylvan scene, already rich to luxuriance in massive foliage, and stately growth. The present house was built by the first Lord Lyttleton, not on, but near to, the site of the ancient family mansion, a structure of the sixteenth century. Admission may be obtained on application to the housekeeper; and for paintings, carving, and gilding, Hagley is one of the richest show-houses in the kingdom.2

Much as the visiter will admire the refined taste displayed within the mansion, his admiration will be heightened by the classic taste in which the grounds are disposed. A short distance from the house, embosomed in trees, stands the church, built in the time of Henry III.; with a sublime Gothic arch, richly painted windows, and a ceiling fretted with the heraldic fires of the Lyttleton family, whose tombs are placed on all sides; among them, the resting-place of the gay poet is distinguished by the following plain inscription:—

This unadorned stone was placed hereBy the particular desire and expressDirections of the Right HonourableGEORGE, LORD LYTTLETON,Who died August 22, 1773, aged 64.Leaving the church we ascend to the crest of a hill, on which stands the Prince of Wales's Pillar. From this point, the view is inexpressibly beautiful, in which may be seen an octagon seat sacred to the memory of Thomson, and erected on the brow of a verdant steep, his favourite spot. In the foreground is a gently winding valley; on the rising hill beyond is a noble wood, whilst to the right the open country fades in the distance; on the left the Clent hills appear, and a dusky antique tower stands just below them at the extremity of the wood; whilst in the midst of it, we can discern the Doric temple sacred to Pope. This exquisite gem of the picturesque is represented in our Engraving.

In the adjoining grove of oaks is the antique tower; in a beautiful amphitheatre of wood, an Ionic rotunda; and in an embowering grove a Palladian bridge, with a light airy portico. Here on a fine lawn is the urn inscribed to Pope, mentioned by Shenstone:

Here Pope! ah, never must that towering mindTo his loved haunts, or dearer friend return;What art, what friendship! oh! what fame resign'd;In yonder glade I trace his mournful urn.At the end of the valley, in an obscure corner is a hermitage, composed of roots and moss, whence we look down on a piece of water in the hollow, thickly shaded with tall trees, (see the engraving,) over which is a fine view of distant landscape. This spot is the extremity of the park, and the Clent hills rise in all their wild irregularity, immediately behind it.

We have not space to describe, or rather to abridge from Whately's beautiful description, a tithe of the classic embellishments of Hagley. Shenstone as well as Pope has here his votive urn. Ivied ruin, temple, grotto, statue, fountain, and bridge; the proud portico and the humble rustic seat, alternate amidst these ornamental charms, and never were Nature and art more delightfully blended than in the beauties of Hagley. Here Pope, Shenstone, and Thomson3 passed many hours of calm contemplation and poetic ease, amidst the hospitalities of the noble owner of Hagley. To think of their kindred spirits haunting its groves, and their imaginative contrivances of votive temples, urns, and tablets, and to combine them with these enchanting scenes of Nature, is to realize all that Poets have sung of Arcadia of old. Happy! happy life for the man of letters; what a retreat must your bowers have afforded from the common-place perplexities of every-day life: Alas! the picture is almost too sunny for sober contemplation.

In part of the impression of our last Number, we stated the architect of the front of Apsley House, to be Sir Jeffrey Wyatville, instead of Mr. Benjamin Wyatt, by whom the design was furnished, and under whose superintendence this splendid improvement has been executed. Mr. B. Wyatt is likewise the architect of the superb mansion built for the late Duke of York.

INGRATITUDE.

A DRAMATIC SKETCH

(For the Mirror.)Hence, faithless wretch! thou hast forgot the handThat sav'd thee from oppression—from the graspOf want. I fed you once—then you was poor:Even as I am now. Yet from the storeOf your abundance, you refuse to grantThe veriest trifle. May the bountyOf that great God who gave you what you haveNe'er from you flow. You have forgot me, sir,But I remember ere I left this land,By way of traffic for the western world,I had a favourite, faithful dog,Who for the kindnesses I pour'd upon himWould fawn upon me: not in flattery,But in a sort that spoke his generous nature.Lasting as memory,Faster than friendship—deeper than the waveIs the affection of a mindless brute.In a few hours (for I can almost seeThe cot wherein these travell'd bones were cradled,)I shall have ended an untoward enterprize,And if that honest creature I have told you ofStill breathes this vital air, and will not know me,May hospitality keep closed her gatesAgainst me, till I find a home withinThe grave.CYMBELINE.M. BOILEAU TO HIS GARDENER.

IMITATED

(For the Mirror.)Industrious man, thou art a prize to me,The best of masters—surely born for thee;Thou keeper art of this my rural seat,4Kept at my charge to keep my garden neat;To train the woodbine and to crop the yew—In th' art of gard'ning equall'd p'rhaps by few.O! could I cultivate my barren soul,As thou this garden canst so well control;Pluck up each brier and thorn, by frequent toil,And clear the mind as thou canst cleanse the soil5But now, my faithful servant, Anthony,Just speak, and tell me what you think of me;When through the day amidst the gard'ning tradeYou bear the wat'ring pot, or wield the spade,And by your labour cause each part to yield,And make my garden like a fruitful field;What say you, when you see me musing thereWith looks intent as lost in anxious care,And sending forth my sentiments in wordsThat oft intimidate the peaceful birds?Dost thou not then suppose me void of rest,Or think some demon agitates my breast?Yon villagers, you know, are wont to sayThy master's fam'd for writing many a lay,'Mongst other matters too he's known to singThe glorious acts of our victorious king;6Whose martial fame resounds thro' every town;Unparallel'd in wisdom and renown.You know it well—and by this garden wallP'rhaps Mons and Namur7 at this instant fall.What shouldst thou think if haply some should sayThis noted chronicler's employ'd to-dayIn writing something new—and thus his timeDevotes to thee—to paint his thoughts in rhyme?My master, thou wouldst say, can ably teach,And often tells me more than parsons preach;But still, methinks, if he was forc'd to toilLike me each day—to cultivate the soil,To prune the trees, to keep the fences round;Reduce the rising to the level ground,Draw water from the fountains near at handTo cheer and fertilize the thirsty land,He would not trade in trifles such as these,And drive the peaceful linnets from the trees.Now, Anthony, I plainly see that youSuppose yourself the busiest of the two;But ah, methinks you'd tell a diff'rent taleIf two whole days beyond the garden paleYou were to leave the mattock and the spadeAnd all at once take up the poet's trade:To give a manuscript a fairer face,And all the beauty of poetic grace;Or give the most offensive flower that blowsCarnation's sweets, and colours of the rose;And change the homely language of the clownTo suit the courtly readers of the town—Just such a work, in fact, I mean to say,As well might please the critics of the day!Soon from this work returning tir'd and lean,More tann'd than though you'd twenty summers seen,The wonted gard'ning tools again you'd takeYour long-accustom'd shovel and your rake;And then exclaiming, you would surely say,'Twere better far to labour many a dayThan e'er attempt to take such useless flights,And vainly strive to gain poetic heights,Impossible to reach—I might as soonAscend at once and land upon the moon!Come, Anthony, attend: let me explain(Although an idler) weariness and pain.Man's ever rack'd and restless, here below,And at his best estate must labour know.Then comes fatigue. The Sisters nine may pleaseAnd promise poets happiness and ease;But e'en amidst those trees, that cooling shade,That calm retreat for them expressly made,No rest they find—there rich effusions flowIn all the measures bardic numbers know:Thus on their way in endless toil they move,And spend their strength in labours that they love.Beneath the trees the bards the muses haunt,And with incessant toil are seen to pant;But still amidst their pains, they pleasure findAn ample entertainment for the mind.But, after all, 'tis plain enough to me,A man unstudious, must unhappy be;Who deems a dull, inactive life the best,A life of laziness, a life of rest;A willing slave to sloth—and well I know,He suffers much who nothing has to do.His mind beclouded, he obscurely sees,And free from busy life imagines ease.All sinful pleasures reign without control,And passions unsubdued pollute the soul;He thus indulges in impure desires,Which long have lurk'd within, like latent fires:At length they kindle—burst into a flameOn him they sport—sad spectacle of shame.Remorse ensues—with every fierce disease.The stone and cruel gout upon him seize;To quell their rage some fam'd physicians comeWho scarce less cruel, crowd the sick man's room;On him they operate—these learned folk,Make him saw rocks, and cleave the solid oak;8And gladly would the man his fate resignFor such an humble, happy state as thine.Be thankful, Anthony, and think with me,The poor hardworking man may happier beIf blest with strength, activity, and health,Than those who roll in luxury and wealth.Two truths important, I proceed to tell,One is a truth, you surely know full well;That labour is essential here belowTo man—a source of weal instead of woe:The other truth, few words suffice to prove,No blame attaches to the life I love.So still attend—but I must say no more,I plainly see, you wish my sermon o'er;You gape, you close your eyes, you drop your chin,Again methinks I'd better not begin.Besides, these melons seem to wish to knowThe reason why they are neglected so;And ask if yonder village holds its feastAnd thou awhile art there detained a guest,While all the flowery tribes make sad complaint.For want of water they are grown quite faint.Tipton.T.S.A.THE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

LIVES OF BRITISH PAINTERS, SCULPTORS, AND ARCHITECTS

By Allan CunninghamThis volume is the first of a series of Lives of Artists, and the fourth number of Murray's Family Library. The author is a first-rate poet, but it appears that he undertook this task with some diffidence. We have, however, few artists of literary attainments, and they are more profitably employed than in authorship. Little apology was necessary, for of all literary men, poets are best calculated to write on the Fine Arts: and the genius of Poetry, Painting, Sculpture, and Music, is often associated in one mind, in love of the subjects at least, if not in practice.

Prefixed to the "Lives," is a delightful chapter on British Art before the birth of Hogarth, from which we quote the following:—

"Poetry, Painting, Sculpture, and Music, are the natural offspring of the heart of man. They are found among the most barbarous nations; they flourish among the most civilized; and springing from nature, and not from necessity or accident, they can never be wholly lost in the most disastrous changes. In this they differ from mere inventions; and, compared with mechanical discoveries, are what a living tree is to a log of wood. It may indeed be said that the tongue of poetry is occasionally silent, and the hand of painting sometimes stayed; but this seems not to affect the ever-living principle which I claim as their characteristic. They are heard and seen again in their season, as the birds and flowers are at the coming of spring; and assert their title to such immortality as the things of earth may claim. It is true that the poetry of barbarous nations is rude, and their attempts at painting uncouth; yet even in these we may recognise the foreshadowings of future excellence, and something of the peculiar character which, in happier days, the genius of the same tribe is to stamp upon worthier productions. The future Scott, or Lawrence, or Chantrey, may be indicated afar-off in the barbarous ballads, drawings, or carvings, of an early nation. Coarse nature and crude simplicity are the commencement, as elevated nature and elegant simplicity are the consummation of art.

"When the Spaniards invaded the palaces of Chili and Peru, they found them filled with works of art. Cook found considerable beauty of drawing and skill of workmanship in the ornamented weapons and war-canoes of the islanders of the South Sea; and in the interior recesses of India, sculptures and paintings, of no common merit, are found in every village. In like manner, when Caesar landed among the barbarians of Britain, he found them acquainted with arts and arms; and his savage successors, the Saxons, added to unextinguishable ferocity a love of splendour and a rude sense of beauty, still visible in the churches which they built, and the monuments which they erected to their princes and leaders. All those works are of that kind called ornamental: the graces of true art, the truth of action and the dignity of sentiment are wanting; and they seem to have been produced by a sort of mechanical process, similar to that which creates figures in arras. Art is, indeed, of slow and gradual growth; like the oak, it is long of growing to maturity and strength. Much knowledge of colour, much skill of hand, much experience in human character, and a deep sense of light and shade, have to be acquired, to enable the pencil to embody the conceptions of genius. The artist has to seek for all this in the accumulated mass of professional knowledge: which time has gathered for his instruction, and with his best wisdom, and his happiest fortune, he can only add a little more information to the common stock, for the benefit of his successors. In no country has Painting risen suddenly into eminence. While Poetry takes wing at once, free and unincumbered, she is retarded in her ascent by the very mechanism to which she must at last owe at least half her glory. In Britain, Painting was centuries in throwing off the fetters of mere mechanical skill, and in rising into the region of genius. The original spirit of England had appeared in many a noble poem, while the two sister arts were still servilely employed in preserving incredible legends, in taking the likeness of the last saint whom credulity had added to the calendar, and in confounding the acts of the apostles in the darkness of allegory."

Then follows an outline of early Art in England, in the embellishment of cathedrals, &c.; among which is the following notice of one of the earliest of our attempts at historical portraiture which can be authenticated:—

"It is a Painting on Wood; the figures are less than life, and represent Henry the Fifth and his relations. It measures four feet six inches long, by four feet four inches high, and was in the days of Catholic power the altarpiece of the church of Shene. An angel stands in the centre, holding in his hands the expanding coverings of two tents, out of which the king, with three princes, and the queen, with four princesses, are proceeding to kneel at two altars, where crosses, and sceptres, and books are lying. They wear long and flowing robes, with loose hair, and have crowns on their heads. In the background, St. George appears in the air, combating with the dragon, while Cleodelinda kneels in prayer beside a lamb. It is not, indeed, quite certain that this curious work was made during the reign of Henry the Fifth, but there can be little doubt of its being painted as early as that of his son."

In the next page we have the following character of an English artist of about the same period:—

"He was at once architect, sculptor, carpenter, goldsmith, armourer, jeweller, saddler, tailor, and painter. There is extant, in Dugdale, a curious example of the character of the times, and a scale by which we can measure the public admiration of art. It is a contract between the Earl of Warwick and John Rag, citizen and tailor, London, in which the latter undertakes to execute the emblazonry of the earl's pageant in his situation of ambassador to France. In the tailor's bill, gilded griffins mingle with Virgin Marys; painted streamers for battle or procession, with the twelve apostles; and 'one coat for his grace's body, lute with fine gold,' takes precedence of St. George and the Dragon."

We wish some of the criticism in this chapter had been milder, and a few of the invectives not so highly charged; some of them even out-Herod the fury of an article on Painting, in a recent number of the Edinburgh Review. But we must pass on to pleasanter matters—as the following poetical paragraphs:—

"The art of tapestry as well as the art of illuminating books, aided in diffusing a love of painting over the island. It was carried to a high degree of excellence. The earliest account of its appearance in England is during the reign of Henry the Eighth, but there is no reason to doubt that it was well known and in general esteem much earlier. The traditional account, that we were instructed in it by the Saracens, has probably some foundation. The ladies encouraged this manufacture by working at it with their own hands; and the rich aided by purchasing it in vast quantities whenever regular practitioners appeared in the market. It found its way into church and palace—chamber and hall. It served at once to cover and adorn cold and comfortless walls. It added warmth, and, when snow was on the hill and ice in the stream, gave an air of social snugness which has deserted some of our modern mansions.

"At first the figures and groups, which rendered this manufacture popular, were copies of favourite paintings; but, as taste improved and skill increased, they showed more of originality in their conceptions, if not more of nature in their forms. They exhibited, in common with all other works of art, the mixed taste of the times—a grotesque union of classical and Hebrew history—of martial life and pastoral repose—of Greek gods and Romish saints. Absurd as such combinations certainly were, and destitute of those beauties of form and delicate gradations and harmony of colour which distinguish paintings worthily so called—still when the hall was lighted up, and living faces thronged the floor, the silent inhabitants of the walls would seem, in the eyes of our ancestors, something very splendid. As painting rose in fame, tapestry sunk in estimation. The introduction of a lighter and less massive mode of architecture abridged the space for its accommodation, and by degrees the stiff and fanciful creations of the loom vanished from our walls. The art is now neglected. I am sorry for this, because I cannot think meanly of an art which engaged the heads and hands of the ladies of England, and gave to the tapestried hall of elder days fame little inferior to what now waits on a gallery of paintings."

Passing over Holbein, Sir Antonio Moore, Vandyke, Lely, Kneller, and Thornhill, we come to the lives of Hogarth—Wilson—Reynolds and Gainsborough—from which we select a few characteristic anecdotes and sketches. In noticing Hogarth's early life, Mr. Cunningham has thrown some discredit on a book, which on its publication, made not a little chat among artists:—

"Of those early days I find this brief notice in Smith's Life of Nollekens the sculptor. 'I have several times heard Mr. Nollekens observe, that he had frequently seen Hogarth, when a young man, saunter round Leicester Fields with his master's sickly child hanging its head over his shoulder.' It is more amusing to read such a book than safe to quote it. Hogarth had ceased to have a master for seventeen years, was married to Jane Thornhill, kept his carriage, and was in the full blaze of his reputation, when Nollekens was born."

Among Hogarth's early labours are his Illustrations of Hudibras, published in 1726. These were seventeen plates; and we have lately seen in the possession of Mr. Britton, the architect, eleven original paintings illustrative of Butler's witty poem, and attributed to Hogarth.

From the notices of Hogarth's portraits we select the following:—

"Hogarth's Portrait of Henry Fielding, executed after death from recollection, is remarkable as being the only likeness extant of the prince of English novelists. It has various histories. According to Murphy, Fielding had made many promises to sit to Hogarth, for whose genius he had a high esteem, but died without fulfilling them; a lady accidentally cut a profile with her scissars, which recalled Fielding's face so completely to Hogarth's memory, that he took up the outline, corrected and finished it and made a capital likeness. The world is seldom satisfied with a common account of any thing that interests it—more especially as a marvellous one is easily manufactured. The following, then, is the second history. Garrick, having dressed himself in a suit of Fielding's clothes, presented himself unexpectedly before the artist, mimicking the step, and assuming the look of their deceased friend. Hogarth was much affected at first, but, on recovering, took his pencil, and drew the portrait. For those who love a soberer history, the third edition is ready. Mrs. Hogarth, when questioned concerning it, said, that she remembered the affair well; her husband began the picture—and finished it—one evening in his own house, and sitting by her side.

"Captain Coram, the projector of the Foundling Hospital, sat for his portrait to Hogarth, and it is one of the best he ever painted. There is a natural dignity and great benevolence expressed in a face which, in the original, was rough and forbidding. This worthy man, having laid out his fortune and impaired his health in acts of charity and mercy, was reduced to poverty in his old age. An annuity of a hundred pounds was privately purchased, and when it was presented to him, he said, 'I did not waste the wealth which I possessed in self-indulgence or vain expense, and am not ashamed to own that in my old age I am poor.'