полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 404, December 12, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 404, December 12, 1829

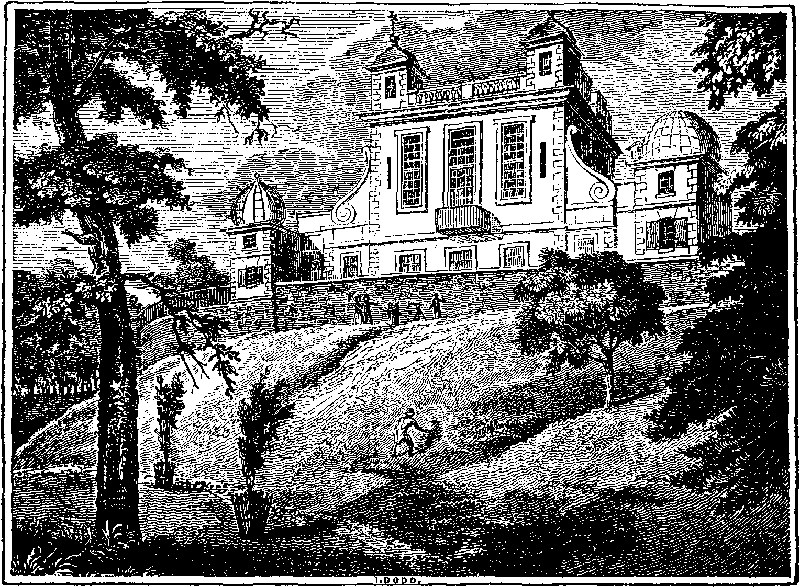

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich

In the present almanack season, as it is technically called, the above illustration of our pages may not be inappropriate or ill-timed, inasmuch as it represents the spot whence all English astronomers make their calculations.

The Observatory was built by Charles II., in the year 1675—probably, observes a recent writer, "with no better motive than to imitate Louis XIV.," who had just completed the erection and endowment of an observatory at Paris. The English Observatory was fortunately placed under the direction of the celebrated Flamstead, whose name the hill, or site of the building, still retains. He was appointed astronomer-royal in 1676; but Charles (as in the case of the curious dial at Whitehall, described by us a few weeks since1), neglected to complete what he had so well begun: and Flamstead entered upon the duties of his appointment with instruments principally provided at his own expense, and that of a zealous patron of science, James Moore. It should seem that this species of parsimony is hereditary in the English Government, for, upon the authority of the Quarterly Review, we learn that "within the wide range of the British Islands there is only one observatory (Greenwich), and scarcely one supported by the Government. We say scarcely one, because we believe that some of the instruments in the observatory at Greenwich were purchased out of the private funds of the Royal Society of London."2

The first stone of this Observatory was laid by Flamstead, on the 10th of August, 1675. It stands 160 feet above low-water mark, and principally consists of two separate buildings: the first contains three rooms on the ground-floor—viz. the transit-room, towards the east, the quadrant-room, towards the west, and the assistant's sitting and calculating-room, in the middle; above which is his bed-room, the latter being furnished with sliding shutters in the roof. In the transit-room is an eight-feet transit-instrument, with an axis of three feet, resting on two piers of stone: this was made by Bird, but has been much improved by Dolland, Troughton, and others. Near it is a curious transit-clock, made by Graham, but greatly improved by Earnshaw, who so simplified the train as to exclude two or three wheels, and also added cross-braces to the gridiron-pendulum, by which an error of a second per day, arising from its sudden starts, was corrected. The quadrant-room has a stone pier in the middle, running north and south, having on its east face a mural-quadrant, of eight feet radius, made by Bird, in 1749, by which observations are made on the southern quarter of the meridian, through an opening in the roof three feet wide, produced by means of two sliding shutters; on its west face is another eight-feet mural quadrant, with an iron frame, and an arch of brass, made by Graham, in 1725: this is applied to the north quarter of the meridian. In the same apartment is the famous zenith-sector, twelve feet in length, with which Dr. Bradley, at Wanstead, and at Kew, made those observations which led to the discovery of the aberration and nutation: here also is Dr. Hooke's reflecting telescope, and three telescopes by Harrison. On the south side of this room is a small building, for observing the eclipses of Jupiter's satellites, occultations, &c., with sliding shutters at the roof and sides, to view any portion of the hemisphere, from the prime verticle down to the southern horizon: this contains a forty-inch achromatic, by the inventor, Mr. John Dolland, with a triple object-glass, a most perfect instrument of its kind; and a five-feet achromatic, by John and Peter Dolland, his sons. Here, likewise, are a two-feet reflecting-telescope (the metals of which were ground by the Rev. Mr. Edwards), and a six-feet reflector, by Dr. Herschell.

The lower part of the house serves merely for a habitation; but above is a large octagonal room, which, being now seldom wanted for astronomical purposes, is used as a repository for such instruments as are too large to be generally employed in the apartments first described, or for old instruments, which modern improvements have superseded. Among the former is a most excellent ten-feet achromatic, by the present Mr. Dolland, and a six-feet reflector, by Short, with a clock to be used with them. In the latter class, besides many curious and original articles, which are deposited in boxes and cupboards, is the first transit instrument that was, probably, ever made, having the telescope near one end of the axis; and two long telescopes with square wooden tubes, of very ancient date. Here, likewise, is the library, which is stored with scarce and curious old astronomical works, including Dr. Halley's original observations, and Captain Cook's Journals. Good busts of Flamstead and Newton, on pedestals, ornament this apartment; and in one corner is a dark narrow staircase, leading to the leads above, whence the prospect is uncommonly grand; and to render the pleasure more complete, there is, in the western turret, a camera obscura, of unrivalled excellence, by which all the surrounding objects, both movable and immovable, are beautifully represented in their own natural colours, on a concave table of plaster of Paris, about three feet in diameter.

On the north side of the Observatory are two small buildings, covered with hemispherical sliding domes, in each of which is an equatorial sector, made by Sisson, and a clock, by Arnold, with a three-barred pendulum, which are seldom used but for observing comets. The celebrated Dry-well, which was made to observe the earth's annual parallax, and for seeing the stars in the day-time, is situated near the south-east corner of the garden, behind the Observatory, but has been arched over, the great improvements in telescopes having long rendered it unnecesary. It contains a stone staircase, winding from the top to the bottom.

The Rev. John Flamstead, Dr. Halley, Dr. Bradley, Dr. Bliss, Dr. Nev. Maskelyne, and John Pond, Esq. have been the successive astronomers-royal since the foundation of this edifice.

TWIN SISTERS

(For the Mirror.)

The most extraordinary instance of this kind on record is that of the united twins, born at Saxony, in Hungary, in 1701; and publicly exhibited in many parts of Europe, among others in England, and living till 1723. They were joined at the back, below the loins, and had their faces and bodies placed half side-ways towards each other. They were not equally strong nor well made, and the most powerful, (for they had separate wills) dragged the other after her, when she wanted to go any where. At six years, one had a paralytic affection of the left side, which left her much weaker than the other. There was a great difference in their functions and health. They had different temperaments; when one was asleep the other was often awake; one had a desire for food when the other had not, &c. They had the small pox and measles at one and the same time, but other disorders separately. Judith was often convulsed, while Helen remained free from indisposition; one of them had a catarrh and a cholic, while the other was well. Their intellectual powers were different; they were brisk, merry, and well bred; they could read, write, and sing, very prettily; could speak several languages, as Hungarian, German, French, and English. They died together, and were buried in the Convent of the Nuns of St. Ursula, at Presburgh.

P.T.W.

ELEGY ON THE DEATH OF A SPARROW

Catullus, Carmen 3(For the Mirror.)

Oh, mourn ye deities of love.And ye whose minds distress can move,Bewail a Sparrow's fate;The Sparrow, favourite of my fair,Fond object of her tend'rest care,Her loss indeed how great.For so affectionate it grew,And its delighted mistress knewAs well as she her mother;Nor would it e'er her lap forsake,But hopping round about would makeSome sportive trick or other.It now that gloomy road has pass'd.That road which all must go at last,From whence there's no retreat;But evil to you, shades of death,For having thus deprived of breathA favourite so sweet.Oh, shameful deed! oh, hapless bird!My charmer, since its death occurr'd,So many tears has shed,That her dear eyes, through pain and grief,And woe, admitting no relief,Alas, are swoln and red.T.C.

FINE ARTS

GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE

(For the Mirror.)

The following explanation of a few of the terms employed to designate parts of Gothic architecture, may, perhaps, prove acceptable to some of your readers. Having felt the need of such assistance in the course of my own reading, &c. &c.—I extracted them from an expensive work on the subject, and have only to lament that my vocabulary should be so defective.

Buttresses.—Projections between the windows and at the corners.

Corbel.—An ornamental projection from the wall to support an arch, niche, beam, or other apparent weight. It is often a head or part of a figure.

Bands.—Either small strings around shafts, or horizontal lines of square, round, and other formed panels, used to ornament spires, towers, and similar works.

Cornice.—The tablet at the top of a wall, running under the battlement. It becomes a

Basement when at the bottom of it, and beneath this the wall is generally thicker.

Battlement.—It may be indented or plain; sunk, panelled, or pierced.

Crockets.—Small bunches of foliage, ornamenting canopies and pinnacles.

Canopies.—Adorned drip-stones.—Vide Dripstone.

Crypts.—Vaulted chapels under some large churches, and a few small ones.

Crisps.—Small arches; sometimes double-feathered, and according to the number of them in immediate connexion; they are termed tre-foils, quatre-foils, cinque-foils, &c.

Dripstone.—The tablet running round doors and windows.

Featherings or Foliations.—Parts of tracery ornamented with small arches and points, are termed Feathered, or Foliated.

Finials.—Large crockets surmounting canopies and pinnacles. This term is frequently applied to the whole pinnacle.

Machicolations.—Projecting battlements, with intervals for discharging missiles on the heads of assailants.

Mullions.—By these, windows are divided into lights.

Parapet.—When walls are crowned with a parapet, it is straight at the top.

Pinnacle.—A small spire, generally four-sided, and placed on the top of buttresses, &c., both exterior and interior.

Piers.—Spaces in the interior of a building between the arches.

Rood Loft.—In ancient churches, not collegiate, a screen between the nave and chancel was so called, which had on the top of it a large projection, whereon were placed certain images, especially those which composed the rood.

Set-offs.—The mouldings and slopes dividing buttresses into stages.

Spandrells.—Spaces, either plain or ornamented, between an arch and the square formed round it.

Stoups.—The basins in niches, which held holy water. Near the altar in old churches, or where the altar has been, is sometimes found another niche, distinguished from the stoup, by having in it at the bottom, a small aperture for carrying off the water; it is often double with a place for bread.

Tabernacle-work.—Ornamented open work over stalls; and generally any minute ornamental open-work.

Tablets.—Small projecting mouldings or strings, mostly horizontal.

Tracery.—Ornaments of the division at the heads of windows. Flowing, when the lines branch out into flowers, leaves, arches, &c. Perpendicular, when the mullions are continued through the straight lines.

Transoms.—The horizontal divisions of windows and panelling.

Turrets.—Towers of great height in proportion to their diameter are so called. Large towers have often turrets at their corners; often one larger than the other, containing a staircase; and sometimes they have only that one.

BRITISH STYLES OF ARCHITECTURE, AND THEIR DURATION

The Norman—Commenced before the conquest, and continued until the reign of Henry II. A.D., 1189. It is characterized by semicircular, and sometimes pointed, arches, rudely ornamented.

Early English.—This style lasted until the reign of Edward I., A.D. 1307. Its characteristics are, pointed arches, long narrow windows, and the jagged or toothed ornament.

Decorated English—Lasted to the end of Edward III., A.D. 1377. It is characterized by large windows with pointed arches divided into many lights by mullions. The tracery of this style is in flowing lines, forming figures. It has many ornaments, light and delicately wrought.

Perpendicular English.—This last style employed latterly only in additions, was in use, though much debased, even as late as 1630-40. The latest whole building in it, is not later than Henry VIII. Its characteristics are the mullions of the windows, and ornamental panelings, run in perpendicular lines; and many buildings in this style are so crowded with ornament, that the beauty of the style is destroyed. The carvings of it are delicately executed.

M.L.B.

THE NOVELIST

ABAD AND ADA

A lost leaf from the Arabian Nights(For the Mirror.)

In the days of Caliph Haroun Alraschid, the neighbourhood of Bagdad was infested by a clan of banditti, known by the name of the "Ranger Band." Their rendezvous was known to be the forests and mountains; but their immediate retreat was a mystery time had not divulged.

That they were valiant, the intrepidity with which they attacked in the glare of noonday would demonstrate; that they were numerous, the many robberies carried on in the different parts of the Caliph's dominions would indicate; and that they were bloody, their invariable practice of killing their victim before they plundered him would argue. They had sworn by their Prophet never to betray one another, and by the Angel of Death to shed their blood in each other's defence. No wonder, then, that they were so difficult to be captured; and when taken, no tortures or promises of reward could extract from them any information as to the retreat of their comrades.

One day, as Giafar, the Vizier, and favourite of the Caliph, was walking alone in a public garden of the city, a stranger appeared, who, after prostrating himself before the second man in the empire, addressed him in these words: "High and mighty Vizier of Alraschid, Lord of the realms of Alla upon earth, whose delegate and vicegerent he is, hear the humblest of the sons of men—Vizier, hear me!"

"Speak, son," said the Vizier, "I am patient."

"And," continued the stranger, "what I have to communicate, be pleased to transmit to our gracious and well-beloved Caliph."

"Let me hear thy suit—it may be in my power to assist you," replied the Vizier.

"The beauteous Ada is in the clutches of ruffians," responded the stranger; "and"—

"Well," said the Vizier, "proceed."

"To be brief, the forest bandit snatched her from my arms—we were betrothed. I have applied to a mighty enchanter, the Genius of the Dale, who tells me she is still living, and in the cavern of the bandit—that her beauty and innocence melted the hearts of robbers, and that were they not afraid of their haunt being discovered, they would have restored her to liberty; but where that cavern is was beyond his power to tell. However, he has informed me how I may demand and obtain the assistance of a much more powerful enchanter than himself; but that genius being the help of Muloch, the Spirit of the Mountain, I need the aid of the Caliph himself. May it please the highness of mighty Giafar to bend before the majesty of the Sovereign of the East, and supplicate in behalf of thy servant Abad."

"How," said the Vizier, "can the Caliph be of service to thee?"

"It is requisite," replied the stranger, "that my hand be stained with the blood of the Caliph, before I summon this most mighty fiend!"—

"How!" cried the astonished Vizier, "would'st thou shed the blood of our beloved master?—No, by Alla!"—

"Pardon me," rejoined the stranger, interrupting him, "and Heaven avert that any thought of harm against the father of his people should warm the breast of Abad; I wish only to anoint my finger with as much of his precious blood as would hide the point of the finest needle; and should this most inestimable favour be conferred upon me, I undertake, under pain of suffering all the tortures that human ingenuity can devise, or devilish vengeance inflict, to exterminate the hated race of banditti who now infest the forests of the East."

"Son," said the aged Vizier, "I will plead thy cause; meet me here on the morrow, and in the mean time consider thy request as granted."

"Father, I take my leave; and may the Guardian of the Good shower down a thousand blessings on thy head!"

Abad made a profound obeisance to the Vizier, and they separated: the latter to conduct the affairs of the state, and the former to toil through the more menial labours of the day.

Morning came; Abad was at the appointed spot before sunrise, and waited with impatience for the expected hour when the Vizier was to arrive. The Vizier was punctual; and with him, in a plain habit, was the Caliph himself, who underwent the operation of having blood drawn from him by the hand of Abad.

At midnight, Abad, as he had been directed by the Genius of the Dale, went to the cave of the Spirit of the Mountain. He was alone! It was pitchy dark; the winds howled through the thick foliage of the forest; the owls shrieked, and the wolves bayed; the loneliness of the place was calculated to inspire terror! and the idea of meeting such a personage, at such an hour, did not contribute to the removal of that terror! He trembled most violently. At length, summoning up courage he entered the mystic cell, and commenced challenging the assistance of the Spirit of the Mountain in the following words:

"In the name of the Genius of the Dale I conjure you! by our holy Prophet I command you! by the darkness of this murky night I entreat you! and by the blood of a Caliph, shed by this weak arm, I allure you, most potent Muloch, to appear! Muloch rise! help! appear!"

At this instant the monster appeared, in the form of a human being of gigantic stature and proportions, having a fierce aspect, large, dark, rolling eyes, bushy eyebrows, and a thick black beard—attired in the habit of a blacksmith! He bore a huge hammer in his right hand, and in his left he carried a pair of pincers, in which was grasped a piece of shapeless metal. His eyes flashed with indignation as he flourished the ponderous hammer over his head, as though it had been a small sword—when, striking the metal he held in the forceps, a round, well-formed shield fell from the stroke.

"Mortal!" vociferated the enchanter, in a voice of thunder, "there is thy weapon and defence!"—flinging the weighty hammer on the ample shield, the collision of which produced a sound in unison with the deep bass of Muloch's voice; nor did the reverberation that succeeded cease to ring in the ears of Abad until several minutes after the spectre had disappeared.

Abad rejoiced when the fearful visit was over, and, well pleased with his success, was preparing to depart; but his joy was damped on finding the hammer so heavy that he could not, without difficulty, remove it from off the shield. He left it in the cave, and returned with the shield only, comforting himself that however he might be at a loss for a weapon, he had a shield that would render him invincible.

His next care was to discover the retreat of the robbers, otherwise he was waging a war with shadows. After making every inquiry, and wandering in vain for several months in quest of them, he was not able to obtain a glimpse of the objects of his search. Still they seemed to possess ubiquity. Their depredations continued, murders multiplied, and their attacks became more open and formidable. Missions were sent daily to the royal city from the emirs and governors of provinces residing at a distance with the most lamentable accounts, and soldiers were dispatched in large bodies to scour the country, but all was of no avail.

Abad had almost abandoned himself to despair, when, one lovely evening, as he wandered along the banks of the Tigris, he observed a boat, laden with armed men, sailing rapidly down the river. "These must be a party of the ranger band. Oh, Mahomet!" said he, prostrating himself on the earth, "be thou my guide!" At length the crew landed on the opposite shore, which was a continued series of crags, and fastening a chain attached to the boat to a staple driven into the rock, under the surface of the water, they suffered the vessel to float with the stream beneath the overhanging rocks, which afforded a convenient shelter and hiding place for it, as it was impossible for any one passing up or down the river to notice it.

Having landed, the party ascended the acclivity, when, suddenly halting and looking round, to ascertain that they were not observed, they removed a large rolling stone that blockaded the entrance, and went into what appeared a natural cavern, then closing the inlet. Not a vestige of them remained in sight, and nature seemed to reign alone amidst the sublimest of her works.

Hope again glowed in the breast of Abad; he soon found means for crossing the stream, and marched boldly to the very entrance of the robber's cave, and with all his might attempted to roll the stone from its axis. But here he was again doomed to disappointment: without the possession of the talisman, kept by the captain of the band, he might as well have attempted to roll the mountain on which he stood into the water beneath, as to have shifted the massy portal: the strength of ten thousand men, could their united efforts have been made available at one and the same time, would not have been sufficient even to stir it.

Abad was returning, disappointed and murmuring at his fate, when he bethought himself of the hammer which Muloch, the Spirit of the Mountain, had promised should be of such powerful aid. He hastened to the place where he had left the large instrument, and the next day brought it to the robbers' cave. He was in the act of lifting the massive weight, to have shattered the adamantine stoppage, when he was surprised by a noise behind him. He looked, and saw the banditti trooping up the ravine: they were returning, on horseback, from an expedition of plunder, laden with conquest. Abad hastily, to avoid discovery, struck the large stone with the charmed hammer, when it receded from the blow and, admitting him into the cave, closed itself upon him. The bandit chief, on seeing a stranger enter, ordered his men to advance rapidly up the ravine, which leads from the waters of the Tigris to the very threshold of the cave, embosomed amidst gigantic and stately rocks.

The captain in vain applied the magic talisman to the charmed stone; the more potent shield of Muloch was within. Enraged at being thus thwarted, he demanded admittance. Abad made no reply, but, raising the enchanted hammer against the ponderous bulwark with his whole strength (and he felt as though gifted with more than mortal strength), he, at one tremendous blow, dislodged the stone which had stood at the entrance of the cave, amidst the shock of tempests and the convulsions of nature, from the creation of the world—as hard as adamant, heavy as gold, and as round as the balls on the cupolas of Bagdad. The bulk rolled down the ravine, bearing with it trees and fragments of rock; men and horses, and all meaner obstructions, were crushed to atoms beneath its weight, as it thundered down the sloping track, and occasionally fell over the steep precipices, which only served to increase its velocity! nor did it stop in its headlong career until it had annihilated the whole of the ranger band, and disappeared amidst the boiling foam of the angry Tigris!