полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 09, December 29, 1849

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 09, December 29, 1849

OUR PROGRESS

We have this week been called upon to take a step which neither our best friends nor our own hopes could have anticipated. Having failed in our endeavours to supply by other means the increasing demand for complete sets of our "NOTES AND QUERIES," we have been compelled to reprint the first four numbers.

It is with no slight feelings of pride and satisfaction that we record the fact of a large impression of a work like the present not having been sufficient to meet the demand,—a work devoted not to the witcheries of poetry or to the charms of romance, but to the illustration of matters of graver import, such as obscure points of national history, doubtful questions of literature and bibliography, the discussion of questionable etymologies, and the elucidation of old world customs and observances.

What Mr. Kemble lately said so well with reference to archæology, our experience justifies us in applying to other literary inquiries:—

"On every side there is evidence of a generous and earnest co-operation among those who have devoted themselves to special pursuits; and not only does this tend of itself to widen the general basis, but it supplies the individual thinker with an ever widening foundation for his own special study."

And whence arises this "earnest co-operation?" Is it too much to hope that it springs from an increased reverence for the Truth, from an intenser craving after a knowledge of it—whether such Truth regards an event on which a throne depended, or the etymology of some household word now familiar only to

"Hard-handed men who work in Athens here?"

We feel that the kind and earnest men who honour our "NOTES AND QUERIES" with their correspondence, hold with Bacon, that

"Truth, which only doth judge itself, teacheth that the inquiry of Truth, which is the love-making or wooing of it—the knowledge of Truth, which is the presence of it—and the belief of Truth, which is the enjoying of it—is the sovereign good of human nature."

We believe that it is under the impulse of such feelings that they have flocked to our columns—that the sentiment has found its echo in the breast of the public, and hence that success which has attended our humble efforts. The cause is so great, that we may well be pardoned if we boast that we have had both hand and heart in it.

And so, with all the earnestness and heartiness which befit this happy season, when

"No spirit stirs abroad;The nights are wholesome; when no planet strikes,No fairy takes, no witch hath power to charm,So hallow'd and so gracious is the time,"do we greet all our friends, whether contributors or readers, with the good old English wish,

A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR!

SIR E. DERING'S HOUSEHOLD BOOK

The muniment chests of our old established families are seldom without their quota of "household books." Goodly collections of these often turn up, with records of the expenditure and the "doings" of the household, through a period of two or more centuries. These documents are of incalculable value in giving us a complete insight into the domestic habits of our ancestors. Many a note is there, well calculated to illustrate the pages of the dramatist or the biographer, and even the accuracy of the historian's statements may often be tested by some of the details which find their way into these accounts; as for the more peculiar province of the antiquary, there is always a rich store of materials. Every change of costume is there; the introduction of new commodities, new luxuries, and new fashions, the varying prices of the passing age. Dress in all its minute details, modes of travelling, entertainments, public and private amusements, all, with their cost, are there: and last, though not least, touches of individual character ever and anon present themselves with the force of undisguised and undeniable truth. Follow the man through his pecuniary transactions with his wife and children, his household, his tenantry, nay, with himself, and you have more of his real character than the biographer is usually able to furnish. In this view, a man's "household book" becomes an impartial autobiography.

I would venture to suggest that a corner of your paper might sometimes be profitably reserved for "notes" from these household books; there can be little doubt that your numerous readers would soon furnish you with abundant contributions of most interesting matter.

While suggesting the idea, there happens to lie open before me the account-book of the first Sir Edward Dering, commencing with the day on which he came of age, when, though his father was still living, he felt himself an independent man.

One of his first steps, however, was to qualify this independence by marriage. If family tradition be correct, he was as heedless and impetuous in this the first important step of his life, as he seems to have been in his public career. The lady was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir Nicholas Tufton, afterwards created Earl of Thanet.

In almost the first page of his account-book he enters all the charges of this marriage, the different dresses he provided, his wedding presents, &c. As to his bride, the first pleasing intelligence which greeted the young knight, after passing his pledge to take her for "richer for poorer," was, that the latter alternative was his. Sir Nicholas had jockied the youth out of the promised "trousseau," and handed over his daughter to Sir Edward, with nothing but a few shillings in her purse. She came unfurnished with even decent apparel, and her new lord had to supply her forthwith with necessary clothing. In a subsequent page, when he comes to detail the purchases which he was, in consequence, obliged to make for his bride, he gives full vent to his feelings on this niggardly conduct of the father, and, in recording the costs of his own outfit, his very first words have a smack of bitterness in them, which is somewhat ludicrous—

"Medio de donte leporumSurgit amari aliquid."He seems to sigh over his own folly and vanity in preparing a gallant bridal for one who met it so unbecomingly.

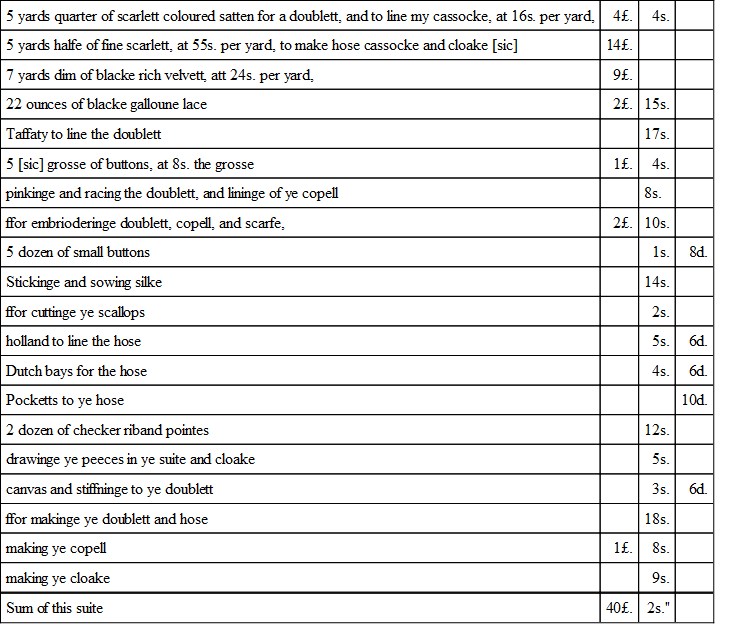

"1619.

"My DESPERATE quarter! the 3d quarter from Michaelmas unto New Year's Day.

I must not occupy more of your space this week by extending these extracts. If likely to supply useful "notes" to your readers, they shall have, in some future number, the remainder of the bridegroom's wardrobe. In whatever niggardly array the bride came to her lord's arms, he, at least, was pranked and decked in all the apparel of a young gallant, an exquisite of the first water, for this was only one of several rich suits which he provided for his marriage outfit; and then follows a list of costly gloves and presents, and all the lavish outlay of this his "desperate quarter."

In some future number, too, if acceptable to your readers, you shall be furnished with a list of other and better objects of expenditure from this household book; for Sir Edward, albeit, as Clarendon depicts him, the victim of his own vanity, was worthy of better fame than is yet been his lot to acquire.

He was a most accomplished scholar and a learned antiquary. He had his foibles, it is true, but they were redeemed by qualities of high and enduring excellence. The eloquence of his parliamentary speeches has elicited the admiration of Southey; to praise them therefore now were superfluous. The noble library which he formed at Surrenden, and the invaluable collection of charters which he amassed there, during his unhappily brief career, testify to his ardour in literary pursuits. The library and a large part of the MSS. are unhappily dispersed. Of the former, all that remains to tell of what it once was, are a few scattered notices among the family records, and the titles of books, with their cost, as they are entered in the weekly accounts of our "household book." Of the latter there yet remain a few thousand charters and rolls, some of them of great interest, with exquisite seals attached. I shall be able occasionally to send you a few "notes" on these heads, from the "household book," and, in contemplating the remains of this unrivalled collection of its day, I can well bespeak the sympathy of every true-hearted "Chartist" and Bibliographer, in the lament which has often been mine—"Quanta fuisti cum tantæ sint reliquiæ!"

LAMBERT B. LARKING.Ryarsh Vicarage, Dec. 12. 1849.BERKELEY'S THEORY OF VISION VINDICATED

In reply to the query of "B.G." (p. 107. of your 7th No.), I beg to say that Bishop Berkeley's Theory of Vision Vindicated does not occur either in the 4to. or 8vo. editions of his collected works; but there is a copy of it in the library of Trinity College, Dublin, from which I transcribe the full title as follows:—

"The Theory of Vision, or Visual Language, shewing the immediate Presence and Providence of a Deity, vindicated and explained. By the author of Alciphron, or The Minute Philosopher.

"Acts, xvii. 28.

"In Him we live, and move, and have our being.

"Lond. Printed for J. Tonson in the Strand.

"MDCCXXXIII."

Some other of the author's tracts have also been omitted in his collected works; but, as I am now answering "a Query," and not making "a Note," I shall reserve what I might say of them for another opportunity. The memory of Berkeley is dear to every member of this University; and therefore I hope you will permit me to say one word, in defence of his character, against Dugald Stewart's charge of having been "provoked," by Lord Shaftesbury's Characteristics, "to a harshness equally unwonted and unwarranted."

Mr. Stewart can scarcely suppose to have seen the book upon which he pronounces this most "unwarranted" criticism. The tract was not written in reply to the Characteristics, but was an answer to an anonymous letter published in the Daily Post-Boy of September 9th, 1732, which letter Berkeley has reprinted at the end of his pamphlet. The only allusion to the writer of this letter which bears the slightest tinge of severity occurs at the commencement of the tract. Those who will take the trouble of perusing the anonymous letter, will see that it was richly deserved; and I think it can scarcely, with any justice, be censured as unbecomingly harsh, or in any degree unwarranted. The passage is as follows:—

[After mentioning that an ill state of health had prevented his noticing this letter sooner, the author adds,] "This would have altogether excused me from a controversy upon points either personal or purely speculative, or from entering the lists of the declaimers, whom I leave to the triumph of their own passions. And indeed, to one of this character, who contradicts himself and misrepresents me, what answer can be made more than to desire his readers not to take his word for what I say, but to use their own eyes, read, examine, and judge for themselves? And to their common sense I appeal."

The remainder of the tract is occupied with a philosophical discussion of the subject of debate, in a style as cool and as free from harshness as Dugald Stewart could desire, and containing, as far as I can see, nothing inconsistent with the character of him, who was described by his contemporaries as the possessor of "every virtue under heaven."

JAMES H. TODD.Trin. Coll. Dublin, Dec. 20. 1849.BISHOP BARNABY

Mr. Editor,—Allow me, in addition to the Note inserted in your 4th Number, in answer to the Query of LEGOUR, by your correspondent (and I believe my friend) J.G., to give the following extract from Forby's Vocabulary of East Anglia:—

"Bishop Barnabee-s. The pretty insect more generally called the Lady-bird, or May-bug. It is one of those highly favoured among God's harmless creatures which superstition protects from wanton injury. Some obscurity seems to hang over this popular name of it. It has certainly no more relation to the companion of St. Paul than to drunken Barnaby, though some have supposed it has. It is sometimes called Bishop Benebee, which may possibly have been intended to mean the blessed bee; sometimes Bishop Benetree, of which it seems not possible to make any thing. The name has most probably been derived from the Barn-Bishop; whether in scorn of that silly and profane mockery, or in pious commemoration of it, must depend on the time of its adoption, before or since the Reformation; and it is not worth inquiring. The two words are transposed, and bee annexed as being perhaps thought more seemly in such a connection than fly-bug or beetle. The dignified ecclesiastics in ancient times wore brilliant mixtures of colours in their habits. Bishops had scarlet and black, as this insect has on its wing-covers. Some remains of the finery of the gravest personages still exist on our academical robes of ceremony. There is something inconsistent with the popish episcopal character in the childish rhyme with which Bishop Barnabee is thrown up and dismissed when he happens to light on any one's hand. Unluckily the words are not recollected, nor at present recoverable; but the purport of them is to admonish him to fly home, and take care of his wife and children, for that his house in on fire. Perhaps, indeed, the rhyme has been fabricated long since the name by some one who did not think of such niceties."

G.A.C.Sir,—In the explanation of the term Bishop Barnaby, given by J.G., the prefix "Bishop" seems yet to need elucidation. Why should it not have arisen from the insect's garb? The full dress gown of the Oxford D.D.—scarlet with black velvet sleeves—might easily have suggested the idea of naming the little insect "Dr. Burn bug," and the transition is easy to "Dr. Burnabee," or "Bishop Burnaby." These little insects, in the winter, congregate by thousands in barns for their long slumber till the reappearance of genial weather, and it is not impossible that, from this circumstance, the country people may have designated them "Barn bug," or "Barn bee."

L.B.L.Sir,—I cannot inform LEGOUR why the lady-bird (the seven-spotted, Coccinella Septempunctata, is the most common) is called in some places "Bishop Barnaby." This little insect is sometimes erroneously accused of destroying turnips and peas in its larva state; but, in truth, both in the larva and perfect state it feeds exclusively on aphides. I do not know that it visits dairies, and Tusser's "Bishop that burneth," may allude to something else; still there appears some popular connection of the Coccinellidæ with cows as well as burning, for in the West Riding of Yorkshire they are called Cush Cow Ladies; and in the North Riding one of the children's rhymes anent them runs:—

"Dowdy-cow, dowdy-cow, ride away heame,Thy1 house is burnt, and thy bairns are tean,And if thou means to save thy bairnsTake thy wings and flee away!"The most mischievous urchins are afraid to hurt the dowdy-cow, believing if they did evil would inevitably befall them. It is tenderly placed on the palm of the hand—of a girl, if possible—and the above rhyme recited thrice, during which it usually spreads its wings, and at the last word flies away. A collection of nursery rhymes relating to insects would, I think, be useful.

W.G.M.J. BARKER.MATHEMATICAL ARCHÆOLOGY

Sir,—I cannot gather from your "Notes" that scientific archæology is included in your plan, nor yet, on the other hand, any indications of its exclusion. Science, however, and especially mathematical science, has its archæology; and many doubtful points of great importance are amongst the "vexed questions" that can only be cleared up by documentary evidence. That evidence is more likely to be found mixed up amongst the masses of papers belonging to systematic collectors than amongst the papers of mere mathematicians—amongst men who never destroy a paper because they have no present use for it, or because the subject does not come within the range of their researches, than amongst men who value nothing but a "new theorem" or "an improved solution."

As a general rule I have always habituated myself to preserve every scrap of paper of any remote (and indeed recent) period, that had the appearance of being written by a literary man, whether I knew the hand, or understood the circumstance to which it referred, or not. Such papers, whether we understand them or not, have a possible value to others; and indeed, as my collections have always been at the service of my friends, very few indeed have been left in my hands, and those, probably, of no material value.

I wish this system were generally adopted. Papers, occasionally of great historical importance, and very often of archæological interest, would thus be preserved, and, what is more, used, as they would thus generally find their way into the right hands.

There are, I fancy, few classes of papers that would be so little likely to interest archæologists in general, as those relating to mathematics; and yet such are not unlikely to fall in their way, often and largely, if they would take the trouble to secure them. I will give an example or two, indicating the kind of papers which are desiderata to the mathematical historian.

1. A letter from Dr. Robert Simson, the editor of Euclid and the restorer of the Porisms, to John Nourse of the Strand, is missing from an otherwise unbroken series, extending from 1 Jan. 1751 to near the close of Simson's life. The missing letter, as is gathered from a subsequent one, is Feb. 5. 1753. A mere letter of business from an author to his publisher might not be thought of much interest; but it need not be here enforced how much of consistency and clearness is often conferred upon a series of circumstances by matter which such a letter might contain. This letter, too, contains a problem, the nature of which it would be interesting to know. It would seem that the letter passed into the hands of Dodson, editor of the Mathematical Repository; but what became of Dodson's papers I could never discover. The uses, however, to which such an unpromising series of letters have been rendered subservient may be seen in the Philosophical Magazine, under the title of "Geometry and Geometers," Nos. ii. iii. and iv. The letters themselves are in the hands of Mr. Maynard, Earl's Court, Leicester Square.

2. Thomas Simpson (a name venerated by every geometer) was one of the scientific men consulted by the committee appointed to decide upon the plans for Blackfriars Bridge, in 1759 and 1760.

"It is probable," says Dr. Hutton, in his Life of Simpson, prefixed to the Select Exercises, 1792, "that this reference to him gave occasion to his turning his thoughts more seriously to this subject, so as to form the design of composing a regular treatise upon it: for his family have often informed me that he laboured hard upon this work for some time before his death, and was very anxious to have completed it, frequently remarking to them that this work, when published, would procure him more credit than any of his former publications. But he lived not to put the finishing hand to it. Whatever he wrote upon this subject probably fell, together with all his other remaining papers, into the hands of Major Henry Watson, of the Engineers, in the service of the India Company, being in all a large chest full of papers. This gentleman had been a pupil of Mr. Simpson's, and had lodged in his house. After Mr. Simpson's death Mr. Watson prevailed upon the widow to let him have the papers, promising either to give her a sum of money for them, or else to print and publish them for her benefit. But nothing of the kind was ever done; this gentleman always declaring, when urged on this point by myself and others, that no use could be made of any of the papers, owing to the very imperfect state in which he said they were left. And yet he persisted in his refusal to give them up again."

In 1780 Colonel Watson was recalled to India, and took out with him one of the most remarkable English mathematicians of that day, Reuben Burrow. This gentleman had been assistant to Dr. Maskelyne at the Royal Observatory; and to his care was, in fact, committed the celebrated Schehallien experiments and observations. He died in India, and, I believe, all his papers which reached England, as well as several of his letters, are in my possession. This, however, is no further of consequence in the present matter, than to give authority to a remark I am about to quote from one of his letters to his most intimate friend, Isaac Dalby. In this he says:—"Colonel Watson has out here a work of Simpson's on bridges, very complete and original."

It was no doubt by his dread of the sleepless watch of Hutton, that so unscrupulous a person as Colonel Watson is proved to be, was deterred from publishing Simpson's work as his own.

The desideratum here is, of course, to find what became of Colonel Watson's papers; and then to ascertain whether this and what other writings of Simpson's are amongst them. A really good work on the mathematical theory of bridges, if such is ever to exist, has yet to be published. It is, at the same time, very likely that his great originality, and his wonderful sagacity in all his investigations, would not fail him in this; and possibly a better work on the subject was composed ninety years ago than has yet seen the light—involving, perhaps, the germs of a totally new and more effective method of investigation.

I have, I fear, already trespassed too far upon your space for a single letter; and will, therefore, defer my notice of a few other desiderata till a future day.

T.S.D.Shooter's Hill, Dec. 15. 1849.SONG IN THE STYLE OF SUCKLING—THE TWO NOBLE KINSMEN

The song in your second number, furnished by a correspondent, and considered to be in the style of Suckling, is of a class common enough in the time of Charles I. George Wither, rather than Suckling, I consider as the head of a race of poets peculiar to that age, as "Shall I wasting in Despair" may be regarded as the type of this class of poems. The present instance I do not think of very high merit, and certainly not good enough for Suckling. Such as it is, however, with a few unimportant variations, it may be found at page 101. of the 1st vol. of The Hive, a Collection of the most celebrated Songs. My copy is the 2nd edit. London, 1724.

I will, with your permission, take this opportunity of setting Mr. Dyce right with regard to a passage in the Two Noble Kinsmen, in which he is only less wrong than all his predecessors. It is to be found in the second scene of the fourth act, and is as follows:—

"Here Love himself sits smiling:Just such another wanton GanymedeSet Jove afire with," &c.One editor proposed to amend this by inserting the normative "he" after "Ganymede;" and another by omitting "with" after "afire." Mr. Dyce saw that both these must be wrong, as a comparison between two wanton Ganymedes, one of which sat in the coutenance of Arcite, could never have been intended;—another, something, if not Ganymede, was wanted, and he, therefore, has this note:—"The construction and meaning are, 'With just such another smile (which is understood from the preceding 'smiling') wanton Ganymede set Jove afire." When there is a choice of nouns to make intelligible sense, how can that one be understood which is not expressed? It might be "with just such another Love;" but, as I shall shortly show, no conjecture on the subject is needed. The older editors were so fond of mending passages, that they did not take ordinary pains to understand them; and in this instance they have been so successful in sticking the epithet "wanton" to Ganymede, that even Mr. Dyce, with his clear sight, did not see that the very word he wanted was the next word before him. It puts one in mind of a man looking for his spectacles who has them already across his nose. "Wanton" is a noun as well as an adjective; and, to prevent it from being mistaken for an epithet applied to Ganymede, it will in future be necessary to place after it a comma, when the passage will read thus:—