полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 20, No. 560, August 4, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 20, No. 560, August 4, 1832

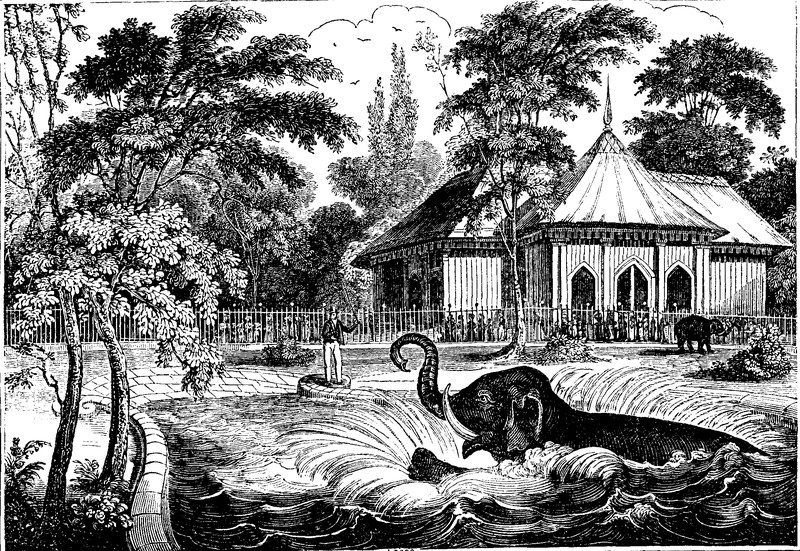

THE ELEPHANTS IN THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, REGENT'S PARK

THE ELEPHANT, IN THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, REGENT'S PARK.

The annexed Engraving will probably afford the reader a better idea of the Zoological Gardens, than did either of our previous Illustrations. It is indeed a fair specimen of the luxurious accommodation afforded by the Society for their animals; while it enables us to watch the habits of the stupendous tenants in a state of nature, or at least, free from unnecessary restriction or confinement. It is an opportunity hitherto but rarely enjoyed in this country; the Elephants exhibited in our menageries being caged up, and only allowed to protrude the head outside the bars. The Duke of Devonshire, as our readers may recollect, possessed an Elephant which died in the year 1829: she was allowed the range of a spacious paddock at Chiswick, but her docility, intelligence, and affection, which were extraordinary, were only witnessed by a few visiters. In the Jardin du Roi, at Paris, the Elephant has long enjoyed advantages proportionate to his importance in the scale of creation. Six years since we remember seeing a fine young specimen in the enjoyment of an ample enclosure of greensward, and a spacious bath has since been added to the accommodations. This example has been rightly followed in our Zoologicai Gardens.

The Elephant Stable is at the extremity of the northern garden in the Regent's Park. It is of capacious dimensions, but is built in a style of unappropriate rusticity. Adjoining the stable is a small enclosure, which the Elephant may measure in two or three turns. Opposite is an enclosure of much greater extent, so as to be almost worthy of the name of a little park or paddock. The fence is of iron, and light but substantial. Within the area are a few lime-trees, the lower branches of which are thinned by the Elephant repeatedly twisting off their foliage with his trunk, as adroitly as a gardener would gather fruit. His main luxury is, however, in his bath, which is a large pool or tank of water, of depth nearly equal to his height. In hot weather he enjoys his ablutions here with great gusto, exhibiting the liveliest tokens of satisfaction and delight. Our artist has endeavoured to represent the noble creature in his bath, though the pencil can afford but an imperfect idea of the extasy of the animal on this occasion. His evolutions are extraordinary for a creature of such stupendous size. His keeper had at first some difficulty in inducing him to enter the pond, but he now willingly takes to the water, and thereby exhibits himself in a point of view in which we have not hitherto been accustomed to view an Elephant in this country. The fondness of Elephants for bathing is very remarkable. When in the water they often produce a singular noise with their trunks. Bishop Heber describes this habit as he witnessed it near Dacca:—"A sound struck my ear, as if from the water itself on which we were riding, the most solemn and singular I can conceive. It was long, loud, deep, and tremulous, somewhat between the bellowing of a bull and the blowing of a whale, or perhaps most like those roaring buoys which are placed at the mouths of some English harbours, in which the winds make a noise to warn ships off them. 'Oh,' said Abdallah, 'there are Elephants bathing: Dacca much place for Elephant.' I looked immediately, and saw about twenty of these fine animals, with their heads and trunks just appearing above the water. Their bellowing it was which I had heard, and which the water conveyed to us with a finer effect than if we had been on shore." The Elephant can also eject from his trunk water and dust, and his own saliva, over every part of his body, to cool its heated surface; and he is said to grub up dust, and blow it over his back and sides, to keep off the flies.

There are two Elephants in the Zoological Gardens. Both are of the Asiatic species. The larger animal was purchased by the Society about fifteen months since. It is probably about eleven years old, and is still growing; and a register of its bulk at various periods has been commenced. The smaller Elephant was presented to the Society by Sir Edward Barnes, late governor of Ceylon. It has been stated to be a dwarf variety, and that its age is not far short of that of the larger individual; but this assertion is questionable. It is much more consistent with our knowledge of the species to regard it, in the absence of all previous knowledge of the history of the individual, as a young one not exceeding four years old. This specimen will be seen in the distance of the Engraving.1

STANZAS ON REVISITING LUDLOW CASTLE

Pale ruin! once more as I gaze on thy walls,What memories of old, the sad vision recalls,For change o'er thee lightly has past;Yet what hearts are estrang'd and what bright hopes are fled,And friends I erst dwelt with now sleep with the dead,Since in childhood I gazed on thee last!Thine image still rests on the clear stream beneath,And flow'rs as of yore, thy old battlement wreathe,Like rare friends by adversity's side;Still clinging aloft, the wild tree I beholdThat marks in derision, the spot, where of oldThe standard once floated in pride.But the conqueror, Time, hath thy banner o'erthrown,And crumbled to ruin the courtyards that shoneWith chivalry's gorgeous array;And where music, and laughter so often have rung,In thy tapestried halls, now the ivy hath flungA mantle to hide their decay.Through the hush of thy lone haunts I wander again,Where these time-hallow'd relics, familiar remain,As if charmed into magic repose;The pass subterraneous,—the fathomless well,The mound whence the violet peeps—and the cellWhere the fox-glove in solitude grows.In the last rays of sunset thy grey turrets gleam,Yet I linger with thee—as to muse o'er a dream,That mournful truths soon will dispel;My pathway winds onward—life's cares to renew,And I feel, as thy towers now fade from my view,'Tis for over—I bid thee farewell!E.L.J.THE NOVELIST

THE HUNTSMAN

A Traditionary Tale: by Miss M.L. Beevor"The merciful man is merciful to his beast.""The worm we tread upon will turn again."Charles, the chief huntsman of Baron Mortimer, was undeniably a very handsome young man, the beau ideal of the lover, as pictured by the glowing imagination of maidens, and the beau real of a dozen villages in the vicinity of Mortimer Castle. Yet, was his beauty not amiable, but rather calculated to inspire terror and distrust, than affection and confidence: in fact, a bandit may be uncommonly handsome; but, by the fierce, haughty character of his countenance, the fire which flashes from his eyes, and the contempt which curls his mustachoed lip, create fear, instead of winning regard, and this was the case with Charles. One, however, of those maidens, unto whom it was the folly and vanity of his youth to pay general court, conceived for him a passion deep and pure, which in semblance, at least, he returned; but how far to answer his own nefarious purposes, for Charles Elliott was a godless young man, we shall hereafter discover.

Annette Martin was the daughter of a small farmer who resided about a mile and a half from the Castle; but, being the tenant of Lord Mortimer, had not only frequent occasion to go thither himself with the rural produce of his farm, (for which the Castle was a ready market,) but also to send Annette. Thus then commenced that innocent girl's acquaintance with the Baron's chief huntsman, not long after Elliott's induction into that office, by the resignation of his superannuated predecessor.

Strange rumours were afloat respecting the conduct of Charles; none of which, it is to be presumed, met the Baron's ears, or assuredly the deprivation of his office would have followed. But Lord Mortimer was a young man, paying his addresses to a lady who lived at some distance from the Castle, and consequently much absent from it. And, what said pretty Annette to the rumours which failed not to meet her ear, of her lover's misconduct? "I don't believe a word of them! Charles may be fonder of pleasure than of business, but he is a young man; by and by he will see and feel the necessity of steady application to the duties of his situation, and become less wild and more manly." "NEVER!" would be solemnly enunciated by Annette's auditors. "As to the charge," would she undauntedly continue, "brought against him of cruelty to the dogs under his care, it is an abominable falsehood; Elliott may be passionate, I don't say he is not, but he is generous and humane. I have never seen him scourge the hounds, as you tell me he does, until blood drops from their mangled hides; I have never heard the cries which, you say, resound from their kennels day and night; cries of pain and hunger."

"And have you never seen," would ask some well-meaning tale-bearer, "any of those poor brutes, whose wealed and mangled coats, proclaimed how savagely they had been treated?"

"I have indeed seen," would answer Annette, "dogs lacerated by the wild boars with which the Castle forests abound."

"And have you never observed the miserable skin-and-bone plight of my lord's hounds?"

"They are not thinner, Charles says, than most hounds in good training: when dogs get fat, they become lazy, lose the faculty of finding game, and the inclination of bringing it down."

"Dogs it is true, ought not to be pampered and surfeited, but they ought to be fed." Upon this, Annette would vehemently maintain that fed they were, and amply, as she had seen Elliott cut up their meat; whilst the friendly newsmonger would charitably hint, that her intended knew as well as most men how to turn an honest penny, by cheating the dogs of their food, and selling it elsewhere.

Annette cared little for inuendos which she attributed chiefly to malice and ill-nature. None are so difficult to convince as those who are obstinately deaf to conviction, and there is an idolatry of affection which sometimes burns fonder and deeper, as its object is contemned and despised by the world. Annette had also some idea, that these, and other reports to the prejudice of Charles, originated with an unsuccessful rival, though poor William Curry, amiable, single-minded, and good-humoured as he was, never breathed in her presence, a syllable to the disparagement of Elliott.

Time sped, and upon an occasion when Lord Mortimer returned for a week or two to his Castle, the conduct of his chief huntsman was reported to him; but Charles with consummate art, so vindicated himself, and so contrived to disgrace his accusers, that when the young baron again left home, he stood higher perhaps than ever, in his confidence and favour.

It was the bright summer-time, the period when rural folks make holiday, (at least they did so then, but times have strangely altered of late in once merry England,) the woods put on their brightest green, and the people their finest clothes, for there were wakes, fairs, and rustic meetings innumerable in the vicinity of the Castle. Charles the huntsman might, as usual, be seen at these fêtes for nothing, but after his late victory, he carried his head higher, assumed a swaggering gait, and looked his neighbours out of countenance with impudent defiance.

The village feasts were not yet over, when late one night, a cavalier, passing through one of the great forests which surrounded Mortimer Castle, beheld, (for it was a moon-light night,) a female form slowly sauntering about the bridle-way in which he was riding, and uttering heavy moans and sobs. At first, taking this figure for something supernatural, the traveller was startled, but quickly recovering himself, he rode boldly up to, and addressed, the object of his idle fears:—"I have been waiting here for hours," replied the young woman, for such indeed she was, "and my friend is not yet come; I am sadly afraid, sir, some accident may have happened to him."

"Him!" quoth the stranger laughing, "O my good girl, if you be waiting for a gentleman, no wonder you're disappointed. He has played you false, rely upon it, and won't come to night,—so you'd better go home."

"O sir! O my Lord!—I cannot—I dare not! What would father and mother say? and what could I say?"

"Ay—Annette,—Annette Martin,—what could you say?"

"Only the truth, your lordship;" replied the poor girl sobbing, and curtseying, "and then they'd turn me out of doors, for they do so hate Charles,—Charles Elliott, your honour,—that they've as good as sworn, as they'll never consent to my marrying him, and so—and so—I was just a waiting here to-night for him to come as he promised he would, and take me away to the far off town, and"—

"And there marry you, I suppose, without your father and mother's consent:—eh, Annette?"

"Yes, my lord, an please you," replied the poor girl with another rustic dip.

"No, Annette," replied the young baron, "it does not quite please me; and Charles, at any rate, unless some very unforeseen circumstance should have detained him, shall know what I think of his present conduct to you. But come,—mount behind me,—I am unexpectedly returning to the Castle, Dame Trueby shall there make you comfortable for to-night, your parents and friends shall never know but that your absence from home was occasioned by a regular visit to her, and your marriage in two or three days, with my sanction, Annette, will, I think, completely settle matters."

The urbane young baron alighting, assisted Annette to mount his noble steed, who, though overwhelmed by his kindness, refused to listen to all the consolation, or banterings, with which he endeavoured to cheer her on her way to Castle Mortimer, choosing rather to believe that some dreadful accident had befallen her lover, than that carelessness, or perfidy, caused his absence. Dame Trueby's account was little calculated to soothe Annette's anxiety, or to satisfy Lord Mortimer respecting Elliott's proceedings.

"I have not seen Charles," said she, "since early this morning, when I heard him say he was going to feed the hounds, poor creatures! and time enough that he did, I think, considering that he left them without a morsel for a whole day and night, whilst he was capering away at Woodcroft Feast; and then,—the beast!—what does he, but comes back so dead drunk that we were forced to carry him up to bed; meanwhile, the hungry brutes, poor dumb souls, just ready to eat one another, have been fit to raise the very dead with their barking, and ramping, and yowling!"

"A sad account is this, Margery."

"A very true one, please your lordship," replied the old housekeeper, testily.

"I don't doubt it," returned Lord Mortimer, "but cannot at this time of night, dame, with Charles absent, and this young woman, his intended wife, wanting some refreshment and a bed (for which indeed I have ample need myself), make any inquiry into the affair. Let Elliott call me in the morning instead of More, do you meanwhile make this young woman as comfortable as you can, and recollect, Mrs. Trueby, that she is come to the Castle upon a visit to you."

Margery curtseyed, and "yessed," and "very welled," with apparent submission, but though she dared not express her thoughts, it was easy to read in her ample countenance, sad suspicions relative to the honour of her noble master, and of the forlorn damsel thus thrust upon her peculiar hospitality. "And," continued Lord Mortimer, "Charles, you are sure, fed the dogs this morning?"

"Don't know, my lord, I'm sure," replied the old housekeeper, doggedly, "I suppose he did, and belike beat 'em too; I only know they've been quiet all day, which, it stands to reason, they wouldn't have been without wittals; but Master Elliott, I've not seen since."

"Not since early this morning, and 'tis now midnight! Where can he be?"

"The Lord knows, sir! after no good I doubt, for he's a wild lad, and these fairs and dances, fairly turn his brain."

Little further passed that night between the young lord and his housekeeper; after taking some refreshment he retired to rest, and poor Annette also sought, under the auspices of circumspect Mistress Margery, repose in Castle Mortimer, little anticipating the singularly dreadful disclosure of the ensuing morning. Charles, in fact, not having returned, one of the inferior serving-men,—who durst not, now that his master was at home, stand upon the punctilio of "not my business," undertook soon after dawn to "see to the hounds," in his stead; when upon opening the door of the large enclosure in which they were kept, he there beheld, to his unutterable consternation and horror, the mangled remnants of the careless and cruel Huntsman: these consisted of his clothes, torn into strips, and dyed in blood, with fragments sufficient of flesh and bone to attest the hideous fact, that the ravenous brutes, had, after their last long fast, sprung upon their tormentor, (awful retribution!) even at the very moment when he appeared amongst them with their long delayed meal, torn him in pieces, and devoured him!

Lord Mortimer, though, he could not in conscience blame his canine favourites, nor forbear regarding his huntsman's fate as a signal instance of the retributive justice of Providence, felt himself obliged to destroy the whole pack, after their ferocious banquet on human flesh; and with tears in his eyes, he forced himself to witness their execution, lest the cupidity or misjudging kindness of any of his retainers, should induce them to mitigate the culprits' doom. The horrid story spread far and wide, and one of its earliest results was the appearance at Castle Mortimer of a poor woman and three young children, who stated in an agony of grief, that she was the lawful wife of the deceased Charles Elliott, whom he had maintained in a distant town, unto whom his visits, when off duty at the Castle, and absent without leave, were sometimes paid, and who, with her children, being suddenly bereaved by his awful demise of their sole hope and support, now humbly threw themselves upon the benevolence of Lord Mortimer for employment and subsistence!

The grief and confusion of poor Annette Martin, upon this discovery of black villany meditated against her by the unprincipled huntsman, and upon its miraculous and awful frustration, may be imagined: yet had it also its beneficial influence; for, whilst shuddering at the fearful end of the wretch who had plotted her destruction, her once fond affection was converted into bitter hatred; and, ere long, blessing and thanking God for her miraculous preservation, and casting the very memory of the deceiver from her heart, she was without much difficulty persuaded to become the wife of William Curry, her once rejected, but really worthy and amiable admirer.

MANNERS AND CUSTOMS

PORTUGAL

(Abridged chiefly from the Rev. Mr. Kinsey's "Portugal Illustrated.")Spaniards and Portuguese.—"Strip a Spaniard of all his virtues, and you make a good Portuguese of him," says the Spanish proverb. I have heard it said more truly, "Add hypocrisy to a Spaniard's vices, and you have the Portuguese character." These nations blaspheme God by calling each other natural enemies. Their feelings are mutually hostile; but the Spaniards despise the Portuguese, and the Portuguese hate the Spaniards.—Southey.

Portugal.—Situated by the side of a country just five times its size, Portugal, but for the advantageous position of its coast, the good faith of England, and the weakness of its hostile neighbour, impassable roads, and numerous strong places, would long since have returned to the primitive condition of an Iberian province; but its separate existence as a nation has been preserved to it by the strength of the British alliance being brought into a glorious co-operation with all its own internal means of defence.—Kinsey.

Column of Disgrace.—About the middle of the last century, the Duke of Aviero was detected in a conspiracy with the Jesuits in Portugal, and accordingly executed. His house, at Belem, was levelled to the ground at the time of the Duke's decapitation, and on the site was erected a column of disgrace, which still remains, though some shops have been erected beside it to hide the inscription; a just symbol of the conduct of the nation on this subject, for what they cannot alter they strive to conceal.

Over the proscenium of the opera-house at Lisbon is a large clock placed rather in advance, whose dexter supporter is old Time with his scythe, and the sinister, one of the Muses playing on a lyre.

A Lisbon Dandy.—A small, squat, puffy figure incased within a large pack-saddle, upon the back of a lean, high-boned, straw-fed, cream-coloured nag, with an enormously flowing tail, whose length and breadth would appear to be each night guarded from discolouration by careful involution above the hocks. Taken, from his gridiron spurs and long pointed boots, up his broad, blue-striped pantaloons, à la Cossaque, to the thrice-folded piece of white linen on which he is seated in cool repose; thence by his cable chain, bearing seals as large as a warming-pan, and a key like an anchor; then a little higher to the figured waistcoat of early British manufacture, and the sack-shapened coat, up to the narrow brim sugar-loaf hat on his head,—where can be found his equal? Nor does he want a nose as big as the gnomon of a dial-plate; and two flanks of impenetrable, deep, black brushwood, extending under either ear, and almost concealing the countenance, to complete the singular contour of his features.

A Lisbon Water-carrier earns about sixpence per day, the moiety of which serves to procure him his bread, his fried sardinha from a cook's stall, and a little light wine perhaps, on holidays,—water being his general beverage, nay, one might almost say, his element. A mat in a large upper room, shared with several others, serves him in winter as a place of repose for the night; but during the summer he frequently sleeps out in the open air, making his filled water-barrel his pillow.

Vanity.—A young Lisbon dandy hearing an Englishman complain of the intolerable filth and stench of his metropolis, retorted that, for his part, when he was in London, it was the absence of that filth, and the want of the smells complained of, that had rendered his residence in our metropolis so disagreeable and uncomfortable to him. "No passion," as Southey says, "makes a man a liar so easily as vanity."

Dogs.—In Lisbon dogs seem to luxuriate under the violence of the heat, and to avoid the shady sides of the streets, though the thermometer of Fahrenheit be at 110 degrees; and scarcely an instance of canine madness is ever known to occur. When the French decreed the extinction of the tribe of curs that infest the streets, no native executioner could be found to put the exterminating law in force; nay, the very measure excited popular indignation.

Golden Sands.—Perhaps originally it was the fabled gold of the Tagus which attracted Jews to Lisbon in such numbers, and the general persuasion indeed is, that the yellow sands of this royal river did actually once produce sufficient gold to make a magnificent crown and sceptre for the amiable hands of that patriot sovereign, the good king Denis.

A Dinner.—A dish of yellow-looking bacalhao, the worst supposable specimen of our saltings in Newfoundland; a platter of compact, black, greasy, dirty-looking rice; a pound, if so much, of poor half-fed meat; a certain proportion of hard-boiled beef, that has never seen the salting pan, having already yielded its nutritious qualities to a swinging tureen of Spartan soup, and now requiring the accompaniment of a satellite tongue, or friendly slice of Lamego bacon, to impait a dull relish to it; potatoes of leaden continuity; dumplings of adamantine contexture, that Carthaginian vinegar itself might fail to dissolve; with offensive vegetables, and something in a round shape, said to be imported from Holland, and called cheese, but more like the unyielding rock of flint in the tenacity of its impenetrable substance; a small quantity of very small wine; abundance of water; and an awful army of red ants, probably imported from the Brazils—the wood of which the chairs and tables are made, hurrying across the cloth with characteristic industry;—such are the principal features of the quiet family dinner-table of the Portuguese.