полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 371, May 23, 1829

We are yet too near the restoration to determine the degree of influence it had on cookery in France. The restoration has introduced into monarchy the representative forms friendly to epicurism, and in this respect it is a true blessing—a new era opened to those who are hungry.

M. Jarrin's fourth edition contains upwards of 500 receipts in Italian confectionery, with plates of improvements, &c. like a cyclopaedian treatise on mechanics; and when our readers know there are "seven essential degrees of boiling sugar," they will pardon the details of the business of this volume. The "degrees" are—1. Le lissé, or thread, large or small; 2. Le perlé, or pearl, le soufflet, or blow; 4. La plume, the feather; 5. Le boulet, the ball, large or small; 6. Le cassé, the crack; and, 7. the caramel. So complete is M. Jarrin's system of confectionery, that he is "independent of every other artist;" for he even explains engraving on steel and on wood. What a host of disappointments this must prevent!

If we look further into, or "drink deep" of the art of confectionery, we shall find it to be a perfect Microcosm—a little creation; for our artist talks familiarly of "producing picturesque scenery, with trees, lakes, rocks, &c.; gum paste, and modelling flowers, animals, figures, &c." with astonishing mimic strife. We must abridge one of these receipts for a "Rock Piece Montée in a lake."

"Roll out confectionery paste, the size of the dish intended to receive it; put into a mould representing your pond a lining of almond paste, coloured pale pink, and place in the centre a sort of pedestal of almond paste, supported by lumps of the same paste baked; when dry put it into the stove. Prepare syrup to fill the hollow of the lake, to represent the water; having previously modelled in gum paste little swans, place them in various parts of the syrup; put it into the stove for three hours, then make a small hole through the paste, under your lake, to drain off the syrup; a crust will remain with the swans fixed in it, representing the water. Next build the rock on the pedestal with rock sugar, biscuits, and other appropriate articles in sugar, fixed to one another, supported by the confectionery paste you have put in the middle, the whole being cemented together with caramel, and ornamented. The moulding and heads should then be pushed in almond paste, coloured red; the cascades and other ornaments must be spun in sugar."

These are, indeed, romantic secrets. Spinning nets and cages with sugar is another fine display of confectionery skill—we say nothing of the nets and cages which our fair friends are sometimes spinning—for the sugar compared with their bonds—are weak as the cords of the Philistines.

THE NATURALIST

ROOKS

We glean the following interesting facts from the Essex Herald, as they merit the record of a Naturalist.

"The voracious habits of the rook, and the vast increase of these birds of late years in certain parts of Essex, has been productive of great mischief, especially in the vicinity of Writtle and of Waltham. Since February last, notwithstanding a vigilant watch, the rooks have stolen sets of potatoes from a considerable breadth of ground at Widford Hall. On the same farm, during the sowing of a field of 16 acres with peas, the number of rooks seen at one time on its surface has been estimated at 1,000, which is accounted for by there being a preserve near, which, at a moderate computation, contains 1,000 nests. But the damage done by rooks at Navestock and Kelvedon Hatch, and their vicinities, within a small circle, has been estimated at £2,000. annually. Many farmers pay from 8s. to 10s. per week, to preserve their seed and plants by watching; but notwithstanding such precautions, acre after acre of beans, when in leaf and clear from the soil, have been pulled up, and the crop lost. The late hurricane proved some interruption to their breeding; and particularly at the estate of Lord Waldegrave, at Navestock, where the young ones were thrown from their nests, and were found under trees in myriads; the very nests blown down, it is said, would have furnished the poor with fuel for a short period."

The writer attributes this alarming increase of rooks to "a desire on the part of gentlemen to cause them to be preserved with the same watchfulness they do their game." The most effectual means of deterring the rook from their depredations, is, he says, "to obtain several of these birds at a period of the year when they can be more easily taken; then cut them open, and preserve them by salt. In the spring, during the seed time, these rooks are to be fastened down to the ground with their wings spread, and their mouths extended by a pebble, as if in great torture. This plan has been found so effectual, that even in the vicinity of large preserves, the fields where the dead birds have been so placed, have not been visited by a single rook."

The scarcity of the rook in France, and the antipathy which the French have to that bird is thus accounted for:—

"The fact has been often related by a very respectable Catholic Priest, who resided many years at Chipping-hill, in Witham, that such was the arbitrary conduct of the owners of abbeys and monasteries in France, in preserving and cultivating the rook and the pigeon, that they increased to such numbers as to become so great a pest, as to destroy the seed when sown, and the young plants as soon as they appeared above the ground; insomuch, that the farmer, despairing of a reward for his labour, besides the loss of his seed, the fields were left barren, and the supply of bread corn was, in consequence, insufficient to meet the necessities of so rapidly increasing a people. The father of the gentleman to whom we have alluded, was, for this offence, one of the first victims to his imprudence. The revolutionary mob proceeded to his residence, from whence they took him, and hung his body upon a gibbet; they next proceeded to destroy the rooks and pigeons which he had cultivated in great numbers, and strived to preserve with the same tenacity as others do in this country. We are told by the son of this martyr to his own folly, that the mob continued to shoot the birds amidst the loudest acclamations, and that they exulted in the idea that in each victim they witnessed the fall of an aristocrat."

THE BANANA TREE

The amount and rapidity of produce of this plant probably exceed that of any other in the known world. In eight or nine months after the sucker has been planted, clusters of fruit are formed; and in about two months more they may be gathered. The stem is then cut down, and a fresh plant, about two-thirds of the height of the parent stem, succeeds, and bears fruit in about three months more. The only care necessary is to dig once or twice a year round the roots. According to our author, on 1,076 square feet, from 30 to 40 banana trees may be planted in Mexico, which will yield in the space of the year 4,414 lbs. avoirdupois of fruit; while the same space would yield only 33 lbs. avoirdupois of wheat, and 99 of potatoes. The immediate effect of this facility of supplying the wants of nature is, that the man who can, by labouring two days in the week, maintain himself and family, will devote the remaining five to idleness or dissipation. The same regions that produce the banana, also yield the two species of manioc, the bitter and the sweet: both of which appear to have been cultivated before the conquest.

—Foreign Quarterly ReviewINDIAN CORN

The most valuable article in South American agriculture, is unquestionably the maize, or Indian corn, which is cultivated with nearly uniform success in every part of the republic. It appears to be a true American grain, notwithstanding many crude conjectures to the contrary. Sometimes it has been known to yield, in hot and humid regions, 800 fold; fertile lands return from 300 to 400; and a return of 130 to 150 fold is considered bad—the least fertile soils giving 60 to 80. The maize forms the great bulk of food of the inhabitants, as well as of the domestic animals; hence the dreadful consequences of a failure of this crop. It is eaten either in the form of unfermented bread or tortillas (a sort of bannock, as it is called in Scotland;) and, reduced to flour, is mingled with water, forming either atolle or various kinds of chicha. Maize will yield, in very favourable situations, two or three crops per year; though it is but seldom that more than one is gathered.

The introduction of wheat is said to have been owing to the accidental discovery, by a negro slave of Cortez, of three or four grains, among some rice which had been issued to the soldiers. About the year 1530, these grains were sown; and from this insignificant source has flowed all the enormous produce of the upper lands of Mexico. Water is the only element necessary to ensure success to the Mexican wheat grower; but it is very difficult to attain this—and irrigation affords the most steady supply.

IbidTHE AGAVE AMERICANA,

On Maguey, is an object of great value in the table land of the interior of Mexico; from this plant is obtained the favourite liquor, the pulque. At the moment of efflorescence, the flower stalk is extirpated, and the juice destined to form the fruit flows into the cavity thus produced, and is taken out two or three times a day for four or five months; each day's produce is fermented for ten or fifteen days; after which the pulque is fit to drink, and before it has travelled in skins, it is a very pleasant, refreshing liquor, to which the Mexicans ascribe as many good qualities as the Highlander does to whiskey. The stems of the maguey can supply the place of hemp, and may be converted into paper. The prickles too are used as pins by the Indians.

—IbidTHE ANECDOTE GALLERY

DOCTOR PARR

Concluded from page 334Parr was evidently fond of living in troubled waters; accordingly, on his removal to Colchester, he got into a quarrel with the trustees of the school on the subject of a lease. He printed a pamphlet about it, which he never published; restrained perhaps by the remarks of Sir W. Jones, who constantly noted the pages submitted to him, with "too violent," "too strong;" and probably thought the whole affair a battle of kites and crows, which Parr had swelled into importance; or, it might be, he suppressed it, influenced by the prospect of succeeding to Norwich school, for which he was now a candidate, and by the shrewd observation of Dr. Foster, "that Norwich might be touched by a fellow feeling for Colchester; and the crape-makers of the one place sympathize with the bag-makers of the other." If the latter consideration weighed with him, it was the first and last time that any such consideration did, Parr being apparently of the opinion of John Wesley, that there could be no fitter subject for a Christian man's prayers, than that he might be delivered from what the world calls "prudence." However it happened, the pamphlet was withheld, and Parr was elected to the school at Norwich.

At Norwich, Parr ventured on his first publications, and obtained his first preferment. The publications consisted of a sermon on "The Truth of Christianity," "A Discourse on Education," and "A Discourse on the Late Fast;" the last of which opens with a mistake singular in Parr, who confounds the sedition of Judas Gaulonitis, mentioned in Josephus, (Antiq. xviii. 1. 1.) with that under Pilate, mentioned in St. Luke, (xiii. 1, 2, 3.); whereas the former probably preceded the latter by twenty years, or nearly. The preferment which he gained was the living of Asterby, presented to him by Lady Jane Trafford, the mother of one of his pupils; which, in 1783, he exchanged for the perpetual curacy of Hatton, in Warwickshire, the same lady being still his patron neither was of much value. Lord Dartmouth, whose sons had also been under his care, endeavoured to procure something for him from Lord Thurlow, but the chancellor is reported to have said "No," with an oath. The great and good Bishop Lowth, however, at the request of the same nobleman, gave him a prebend in St. Paul's, which, though a trifle at the time, eventually became, on the expiration of leases, a source of affluence to Parr in his old age. How far he was from such a condition at this period of his life, is seen by the following incident given by Mr. Field. The doctor was one day in this gentleman's library, when his eye was caught by the title of "Stephens' Greek Thesaurus." Suddenly turning about and striking vehemently the arm of Mr. Field, whom he addressed in a manner very usual with him; he said, "Ah! my friend, my friend, may you never be forced, as I was at Norwich, to sell that work, to me so precious, from absolute and urgent necessity."

But we must on with the Doctor in his career. In 1785, for some reason unknown to his biographer, Parr resigned the school at Norwich, and in the year following went to reside at Hatton. "I have an excellent house, (he writes to a friend,) good neighbours, and a Poor, ignorant, dissolute, insolent, and ungrateful, beyond all example. I like Warwickshire very much. I have made great regulations, viz. bells chime three times as long; Athanasian creed; communion service at the altar; swearing act; children catechized first Sunday in the month; private baptisms discouraged; public performed after second lesson; recovered a 100l. a year left the poor, with interest amounting to 115l., all of which I am to put out, and settle a trust in the spring; examining all the charities."

Here Warwickshire pleases Parr; but Parr's taste in this, and in many other matters, (as we shall have occasion to show by and by,) was subject to change. He soon, therefore, becomes convinced of the superior intellect of the men of Norfolk. He finds Warwickshire, the Boeotia of England, two centuries behind in civilization. He is anxious, however, to be in the commission of the peace for this ill-fated county, and applies to Lord Hertford, then Lord Lieutenant; but the application fails; and again, on a subsequent occasion, to Lord Warwick, and again he is disappointed. What motives operated upon their lordships' minds to his exclusion, they did not think it necessary to avow.

Providence has so obviously drawn a circle about every man, within which, for the most part, he is compelled to walk, by furnishing him with natural affections, evidently intended to fasten upon individuals; by urging demands upon him which the very preservation of himself and those about him compels him to listen to; by withholding from him any considerable knowledge of what is distant, and hereby proclaiming that his more proper sphere lies in what is near;—by compassing, him about with physical obstacles, with mountains, with rivers, with seas "dissociable," with tongues which he cannot utter, or cannot understand; that, like the wife of Hector, it proclaims in accents scarcely to be resisted, that there is a tower assigned to everyman, where it is his first duty to plant himself for the sake of his own, and in the defence of which he will find perhaps enough to do, without extending his care to the whole circuit of the city walls.

The close of Parr's life grew brighter, The increased value of his stall at St. Paul's set him abundantly at his ease: he can even indulge his love of pomp—ardetque cupidine currûs, he encumbers himself with a coach and four. In 1816, he married a second wife, Miss Eyre, the sister of his friend the Rev. James Eyre; he became reconciled to his two grand-daughters, now grown up to woman's estate; he received them into his family, and kept them as his own, till one of them became the wife of the Rev. John Lynes.

In the latter years of his life, Parr had been subject to erysipelas; once he had suffered by a carbuncle, and once by a mortification in the hand. Owing to this tendency to diseased action in the skin, he was easily affected by cold, and on Sunday, the 16th of January, 1825, having, in addition to the usual duties of the day, buried a corpse, he was, on the following night, seized with a long-continued rigor, attended by fever and delirium, and never effectually rallied again. There is a note, however, dated November 2, 1824, addressed by him to Archdeacon Butler, which proves that he felt his end approaching, even before this crisis.

"Dear and Learned Namesake,—This letter is important, and strictly confidential. I have given J. Lynes minute and plenary directions for my funeral. I desire you, if you can, to preach a short, unadorned funeral sermon. Rann Kennedy is to read the lesson and grave service, though I could wish you to read the grave service also. Say little of me, but you are sure to say it well."

Dr. Butler complied with his request, and amply made good the opinion here expressed. He spoke of him like a warm and stedfast friend, but not like that worst of enemies, an indiscreet one; he did not challenge a scrutiny by the extravagance of his praise, nor break, by his precious balms, the head he was most anxious to honour. Dr. Parr's death was tedious, and his faculties, except at intervals, disturbed. He took an opportunity, however, afforded him by one of these intervals, of summoning about his bed his wife, grand-children, and servants; confessed to them his weaknesses and errors, asked their forgiveness for any pain he might have caused them by petulance and haste, and professed "his trust in God, through Christ, for the pardon of his sins." One expression, which Dr. Johnstone reports him to have used on this occasion, is extraordinary—that "from the beginning of his life he was not conscious of having fallen into a crime." Far be it from us to scrutinize the words of a delirious death-bed—These must have been uttered (if, indeed, they are accurately given) either in some peculiar and very limited sense, or else at a moment when a man is no longer accountable to God for what he utters. The latter was, probably, the case: for in the same breath in which he declares "his life, even his early life, to have been pure," he sues for pardon at the hands of his Maker, and acknowledges a Redeemer, as the instrument through which he is to obtain it.

That quickness of feeling and disposition to abandon himself to its guidance, which made Parr an inconsistent man, made him also a benevolent one. Benevolence he loved as a subject for his contemplation, and the practical extension of it as a rule for his conduct. He could scarcely bear to regard the Deity under any other aspect. He would have children taught, in the first instance, to regard him under that aspect alone; simply as a being who displayed infinite goodness in the creation, in the government, and in the redemption of the world. Language itself indicates, that the whole system of moral rectitude is comprised in it—[Greek: energetein], benefacere, beneficencethe generic term being, in common parlance, emphatically restricted to works of charity. Nor was this mere theory in Parr. Most men who have been economical from necessity in their youth, continue to be so, from habit, in their age—but Parr's hand was ever open as day. Poverty had vexed, but had never contracted his spirit; money he despised, except as it gave him power—power to ride in his state coach, to throw wide his doors to hospitality, to load his table with plate, and his shelves with learning; power to adorn his church with chandeliers and painted windows; to make glad the cottages of his poor; to grant a loan, to a tottering farmer; to rescue from want a forlorn patriot, or a thriftless scholar. Whether misfortune, or mismanagement, or folly, or vice, had brought its victim low, his want was a passport to Parr's pity, and the dew of his bounty fell alike upon the evil and the good, upon the just and the unjust. It is told of Boerhaave, that, whenever he saw a criminal led out to execution, he would say, "May not this man be better than I? If otherwise, the praise is due, not to me, but to the grace of God." Parr quotes the saying with applause. Such, we doubt not, would have been his own feelings on such an occasion.

—Quarterly ReviewTHE GATHERER

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.

SONG FROM THE ITALIAN OF P. ROLLI

Babbling current, would you knowWhy I turn to thee again,'Tis to find relief from woe,Respite short from ceaseless pain.I and Sylvio on a dayWere upon thy bank reclin'd,When dear Sylvio swore to me,And thus spoke in accents kind:First this flowing tide shall turnBackward to its fountain head,Dearest nymph, ere thou shall mourn,Thy too easy faith betray'd.Babbling current, backward turn,Hide thee in thy fountain head;For alas, I'm left to mournMy too easy faith betray'd.Love and life pursu'd the swain,Both must have the self-same date,But mine only he could mean,Since his love is turn'd to hate.Sure some fairer nymph than I,From me lures the lovely youth,Haply she receives like me,Vows of everlasting truth.Babbling current should the fairStop to listen on thy shore,Bid her, Sylvio, to beware,Love and truth he oft had sworn.T.HTHE SPRING AND THE MORNING,

A Ballad. Written by Sir Lumley Skeffington, Bart. Inscribed to Miss FooteWhen the frosts of the Winter, in mildness were ending,To April I gave half the welcome of May;While the Spring, fresh in youth, came delightfully blendingThe buds that are sweet, and the songs that are gay.As the eyes fixed the heart on a vision so fair,Not doubting, but trusting what magic was there;Aloud I exclaim'd, with augmented desire,I thought 'twas the Spring, when In truth, 'tis Maria.When the fading of stars, in the regions of splendour,Announc'd that the morning was young in the East,On the upland I rov'd, admiration to render,Where freshness, and beauty, and lustre increas'd.Whilst the beams of the morning new pleasures bestow'd,While fondly I gaz'd, while with rapture I glow'd;In sweetness commanding, in elegance bright,Maria arose! a more beautiful light!Gentleman's MagazineUNEXPECTED REPROOF

The celebrated scholar, Muretus, was taken ill upon the road as he was travelling from Paris to Lyons, and as his appearance was not much in his favour, he was carried to an hospital. Two physicians attended him, and his disease not being a very common one, they thought it right to try something new, and out of the usual road of practice, upon him. One of them, not knowing that their patient knew Latin, said in that language to the other, "We may surely venture to try an experiment upon the body of so mean a man as our patient is." "Mean, sir!" replied Muretus, in Latin, to their astonishment, "can you pretend to call any man so, sir, for whom the Saviour of the world did not think it beneath him to die?"

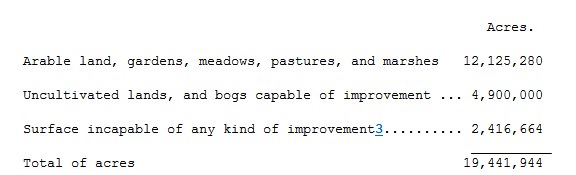

IRELAND

The following is the territorial surface of Ireland:—

3 Parliamentary Report.

ROUGE ET NOIR

When jovial Barras was the Monarch of France,And its women all lived in the light of his glance,One eve, when tall Tallien and plump JosephineWere trying the question, of which should be Queen,Dame Josephine hung on one side of his chair,With her West Indian bosom as brown as 'twas bare;Dame Tallien as fondly on t'other side hung,With a blush that might burn up the spot where she clung.Old Sieyes stalked in; saw my lord at his wine,Now toasting the copper-skin, now the carmine;Then starting away, cried, "Barras, le bon soir;'Twas for business I came; I leave you Rouge et Noir."1

The nightly expenses of Drury Lane and Covent Garden Theatres in these days, are upwards of 200l.

2

"Sweet are the uses of Adversity,Which, like a toad, ugly and venomous,Wears yet, a precious jewel in his head."