полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine — Volume 54, No. 335, September 1843

In a country such as we have described Greece, and we flatter ourselves our description will bear examination on the part of travellers and diplomatic gentlemen, we ask if there can be any doubt of the ultimate success of popular institutions? For our own part, we feel persuaded that Greece can only escape from a fierce civil war by the convocation of a national representative assembly.—We adopted this opinion from the moment that the Bavarian government was unable to destroy the liberty of the press, after plunging into the contest and awakening the political passions of the people. When a sovereign attacks a popular institution without provocation, and fails in his attack, and when the people show that concentrated energy which inspires the prudence necessary to use victory with a moderation which produces no reaction against their cause, their victory is sure. Under such circumstances a nation can patiently wait the current of events. If Greece exist as a monarchy, we believe it will soon have a national assembly; and if King Otho remain its sovereign, we have a fancy that he will not long delay convoking one. Nothing, indeed, can long prevent some representative body from meeting together, unless it be the interference, direct or indirect, of the three protecting powers. They, indeed, have strength sufficient to become the Three Protecting Tyrants.

We hope that we have now given a tolerably intelligible account of King Otho's government, and how it stands. We shall, therefore, proceed to the second division of our enquiry, and strive to explain the actual state of public feeling in Greece; what the king's government was expected to do, and what it has left undone. We may be compelled here to glance at a few delicate and contested questions in Greek politics, on which, however, we shall not pretend to offer any opinion of our own, but merely collect the facts; and we advise all men who wish to form a decided opinion on such a question, to wait patiently until they have been discussed in a national assembly of Greeks.

The first great question on which the government of King Otho was expected to decide, was the means necessary to be adopted for discharging the internal debt contracted for carrying on the war against the Turks. This debt resolved itself into two heads: payment for services, and repayment of money advanced. The national assemblies which had met during the revolution, had decreed that every man who served in the army should, at the conclusion of the war, receive a grant of land. It was proposed that King Otho should carry these decrees into execution, by framing lists of all those who had served either in the army, the navy, or in civil employments. The same registers which contain the lists of the citizens of the various communes, could have been rendered available for the purpose of verifying the services of each individual. A fixed number of acres might then have been destined to each man, according to his rank and time of service. This measure would have enabled the Greek government to say, that it had kept faith with the people. It would have induced many of the military to settle as landed proprietors when the first current of enthusiasm in favour of peaceful occupations set in, and it would have been the means of silencing many pretensions of powerful military chiefs, whose silence has since been dearly purchased.

The royal government always resisted these demands of the Greeks, and the consequence was, that when it was necessary to yield from fear, Count Armansperg adopted a law of dotation, which, under the appearance of being a general measure, was only carried into application in cases where partisanship was established; and yet national lands have been alienated to a far greater extent than would have satisfied every claim arising out of the revolutionary war. The king, it is true, has in late years made donations of national land to favoured individuals, to maids of honour, Turkish neophytes, and Bavarian brides; and he has rewarded several political renegades with currant lands, and held out hopes of conferring villages on councillors of state who have been eager defenders of the court; but all this has been openly done as a matter of royal favour.

With regard to the second class of claimants. Common honesty, if royal gratitude go for nothing in Greece, required that those who advanced money to their country in her day of need, should be repaid their capital. All interest might have been refused—the glory of their disinterested conduct was all the reward they wanted; for few of them would have demanded repayment of the sums due had they been rich enough to offer them as a gift. The refusal of King Otho to repay these sums when he lavished money on his Bavarian favourites and Greek partizans, has probably lowered his character more, both in the East and in Europe, than any of those errors in diplomacy which induced the Morning Chronicle to publish, that several Bavarians of rank had written a certificate of his being an idiot, and forwarded it to his royal father. The sum required to pay up all the claims of this class, would not have exceeded the agency paid by King Otho to his Bavarian banker for remitting the loan contracted at Paris to Greece, by the rather circuitous route of Munich.

It was also expected by the Greeks that one of the first acts of the royal government would have been to abolish the duty on all articles carried by sea from one part of the kingdom to another; this duty amounted to six per cent, and was not abolished until the late demands of the three protecting powers for prompt payment of the money due to them by his Hellenic majesty, rendered King Otho rather more amenable to public opinion than he had been previously. A decree was accordingly published a few months ago, abolishing this most injurious tax, the preamble of which declares, with innocent naïveté, that the duty thus levied is not based on principles of equal taxation, but bears oppressively on particular classes.20 Alas! poor King Otho! he begins to abolish unjust taxation when his exchequer is empty, and when his creditors are threatening him with the Gazette; and yet he delays calling together a national assembly. It is possible that, little by little, King Otho may be persuaded by circumstances to become a tolerable constitutional sovereign at last; but we fear our old friend Hadgi Ismael Bey—may his master never diminish the length of his shadow!—will say on this occasion, as we have heard him say on some others, "Machallah! Truly, the sense of the ghiaour doth arrive after the mischief!" But we hold no opinions in common with Hadgi Ismael Bey, who drinketh water, despiseth the Greek, and hateth the Frank. Our own conjecture is, that King Otho has been studying the history of Theopompus, one of his Spartan predecessors who, like himself, occupied barely half a throne. Colleagues and ephori were in times past as unpleasant associates in the duties of government as protecting powers now are. Now Theopompus looked not lovingly on those who shared his royalty, but as he understood the signs of the times, he sought to make friends at Sparta by establishing a popular council, that is to say, he convoked a national assembly. Thus, by diminishing the pretensions of royalty, he increased its power. Let King Otho do the same, and if some luckless Bavarian statesmen upbraid him with having thrown away his power, let him reply—"No, my friend, I have only rendered the Bavarian dynasty more durable in Greece." [Greek: Oi deta, paraoioômi gar ten basileian poluchroniôteran.] If King Otho would once a day recall to his mind the defence of Missolonghi, if he would reflect on the devotion shown to the cause of their country by the whole population of Greece, he would surely feel prouder of identifying his name and fortunes with a country so honoured and adored, than of figuring in Bavarian history as the protector of the artists who has reared the enormous palace he has raised at Athens.

The Greeks expected that a civilized government would have taken measures for improving the internal communications of the country, and exerted itself to open new channels of commercial enterprise. They had hoped to see some part of the loan expended in the formation of roads, and in establishing regular packets to communicate with the islands. The best road the loan ever made, was one to the marble quarries of Pentelicus in order to build the new palace, and the only packets in Greece were converted by his majesty into royal yachts.21 The regency, it is true, made a decree announcing their determination to make about 250 miles of road. But their performances were confined to repairing the road from Nauplia to Argos, which had been made by Capo d'Istria. The Greek government, however, has now completed the famous road to the marble quarries, a road of six miles in length to the Piraeus, and another of five miles across the isthmus of Corinth. The King of Bavaria very nearly had his neck broken on a road said to have been then practicable between Argos and Corinth. We can answer for its being now perfectly impassable for a carriage. Two considerable military roads are, however, now in progress, one from Athens to Thebes, and another from Argos to Tripolitza. But these roads have been made without any reference to public utility, merely to serve for marching troops and moving artillery, and consequently the old roads over the mountains, as they require less time, are alone used for commercial transport.

It is evident that a poor peasantry, possessing no other means of transport than their mules and pack-horses, must reckon distance entirely by time, and the only way to make them perceive the advantages to be derived from roads, is forming such bridle-paths as will enable them to arrive at their journey's end a few hours sooner. The Greek government never though of doing this, and every traveller who has performed the journey from Patras to Athens, must have seen fearful proofs of this neglect in the danger he ran of breaking his neck at the Kaka-scala or cursed stairs of Megara.

Nay, King Otho's government has employed its vis inertiae in preventing the peasantry, even when so inclined, from forming roads at their own expense; for the peasantry of Greece are far more enlightened than the Bavarians. In the year 1841, the provincial council of Attica voted that the road from Kephisia—the marble-quarry road—should be continued through the province of Attica as far as Oropos. Provision was made for its immediate commencement by the labour of the communes through which it was to pass. Every farmer possessing a yoke of oxen was to give three days' labour during the year, and every proprietor of a larger estate was to supply a proportional amount of labour, or commute it for a fixed rate of payment in money. This arrangement gave universal satisfaction. Government was solicited to trace the line of road; but a year passed—one pretext for delay succeeding another, and nothing was done. The provincial council of 1842 renewed the vote, and government again prevented its being carried into execution. It is said that his Majesty is strongly opposed to the system of allowing the Greeks to get the direction of any public business into their own hands; and that he would rather see his kingdom without roads than see the municipal authorities boasting of performing that which the central government was unable to accomplish.

We shall only trouble our readers with a single instance of the manner in which commercial legislation has been treated in Greece. We could with great ease furnish a dozen examples. Austrian timber pays an import duty of six per cent, in virtue of a commercial treaty between Royal Greece and Imperial Austria. Greek timber cut on the mountains round Athens pays an excise duty of ten per cent; and the value of the Greek timber on the mountains is fixed according to the sales made at Athens of Austrian timber, on which the freight and duty have been paid. The effect can be imagined. In our visit to Greece we spent a few days shooting woodcocks with a fellow-countryman, who possesses an Attic farm in the mountains, near Deceleia. His house was situated amidst fine woods of oak and pine; yet he informed us that the floors, doors, and windows, were all made of timber from Trieste, conveyed from Athens on the backs of mules. The house had been built by contract; and though our friend gave the contractor permission to cut the wood he required within five hundred yards of the house, he found that, what with the high duty demanded by the government, and with the delays and difficulties raised by the officers charged with the valuation, who were Bavarian forest inspectors, the most economical plan was to purchase foreign timber. The consequence of this is, the Greeks burn down timber as unprofitable, and convert the land into pasturage. We have seen many square miles of wood burning on Mount Pentelicus; and on expressing our regret to a Greek minister, he shrugged up his shoulders and said: "That, sir, is the way in which the Bavarian foresters take care of the forests." Yet this Greek, who could sneakingly ridicule the folly of the Bavarians, was too mean to recommend the king to change the law.

Let us now turn to a more enlivening subject of contemplation, and see what the Greeks have done towards improving their own condition. We shall pass without notice all their exertions to lodge and feed themselves, or fill their purses. We can trust any people on those points; our observations shall be confined to the moral culture. We say that the Greeks deserve some credit for turning their attention towards their own improvement, instead of adopting the Gallican system of reform, and raising a revolution against King Otho. They seem to have set themselves seriously to work to render themselves worthy of that liberty, the restoration of which they have so long required in vain from the allied powers. There is, perhaps, no feature in the Greek revolution more remarkable than the eager desire for education manifested by all classes. The central government threw so many impediments in the way of the establishment of a university, that the Greeks perceived that no buildings would be erected either as lecture-rooms for the professors, or to contain the extensive collections of books which had been sent to Greece by various patriotic Greeks in Europe. Men of all parties were indignant at the neglect, and at last a public meeting was held, and it was resolved to raise a subscription for building the university. The government did not dare to oppose the measure; fortunately, there was one liberal-minded man connected with the court at the time, Professor Brandis of Bonn, and his influence silenced the grumbling of the Bavarians; the subscription proceeded with unrivalled activity, and upwards of £.4000 was raised in a town of little more than twenty thousand inhabitants—half the inhabitants of which had not yet been able to rebuild their own houses. Many travellers have seen the new university at Athens, and visited its respectable library, and they can bear testimony to the simplicity and good sense displayed in the building.

One of the most remarkable features of the great moral improvement which has taken place in the population, is the eagerness displayed for the introduction of a good system of female education. The first female school established in Greece was founded at Syra, in the time of Capo d'Istria, by that excellent missionary the late Rev. Dr Korck, who was sent to Greece by the Church Missionary Society. An excellent female school still exists in this island, under the auspices of the Rev. Mr Hilner, a German missionary ordained in England, and also in connexion with the Church Missionary Society. The first female school at Athens, after the termination of the Revolution, was established by Mrs Hill, an American lady, whose exertions have been above all praise. A large female school was subsequently formed by a society of Greeks, and liberally supported by the Rev. Mr Leeves, and many other strangers, for the purpose of educating female teachers. This society raises about £.800 per annum in subscriptions among the Greeks. We cannot close the subject of female education without adding a tribute of praise to the exertions of Mrs Korck, a Greek lady, widow of the excellent missionary whom we have mentioned as having founded the first female school at Syra; and of Mr George Constantinidhes, a Greek teacher, who commenced his studies under the auspices of the British and Foreign School Society, and who has devoted all his energy to the cause of the education of his countrymen, and has always inculcated the great importance of a good system of female education. We insist particularly on the merits of those who devoted their attention to this subject, as indicating a deep conviction of the importance of moral and religious instruction. Male education leads to wealth and honours. Boys gain a livelihood by their learning, but girls are educated that they may form better mothers.

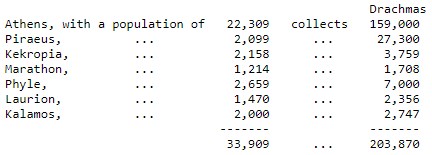

Other public institutions have not been neglected. The citizens of Athens have built a very respectable civil hospital, and we mention this as it is one of the public buildings which excites the attention of strangers, and which is often supposed to have been erected by the government, though entirely built from the funds raised by local taxes. The amount of municipal taxes which the Greeks pay, is another subject which deserves attention. The general taxes in Greece are very heavy. Every individual pays, on an average, twelve shillings, which makes the payment of a family of five persons amount to £.3 sterling annually. This is a very large sum, when the poverty and destitution of the people is taken into consideration, and is greater than is paid by any other European nation where the population is so thinly scattered over the surface of the country. Yet as soon as the Greeks became convinced that the general government would contribute nothing towards improving the country, they determined to impose on themselves additional burdens rather than submit to wait. Hospitals, schools, churches, and bridges, built by several municipalities, attest the energy of the determination of the people to make every sacrifice to improve their condition. We offer our readers a statement of the amount of the taxes imposed by the municipalities of Attica on themselves for local improvements. The town communes of Athens and the Piraeus find less difficulty in collecting the large revenues they possess, than the country districts their comparatively trifling resources.

From this statement we find that each family of five persons pays, on an average, thirty drachmas of self-imposed taxes, or about twenty-two shillings annually, in addition to the £.3 sterling paid to the general government.

We think we may now ask: Are the Greeks fit for a representative system of government? We should like to hear the reasons of those who hold the opinion, that they are not yet able to give an opinion on the best means of improving their own country, and the most advantageous mode of raising the necessary revenue.

We must now conclude with a few remarks on the line of conduct towards the Greeks which has been pursued by the three protecting powers. We do not, however, propose entering at any length on the subject, as we have no other object than that of rendering our preceding observations more clear to our readers. We are persuaded that the policy of interfering as little as possible in the affairs of Greece, which has been adopted, and impartially acted on by Lord Aberdeen, is the true policy of Great Britain.

But in reviewing the general position of the Greek state, it must not be forgotten that the Greek people have had communications with the great powers of Europe of a nature very different from those which existed between the protecting powers and King Otho. As soon as it became evident that Turkey could not suppress the Greek revolution without suffering most seriously from the diminution of her resources, Russia and England began to perceive that it would be a matter of some importance to secure the good-will of the Greek population. The Greeks scattered over the countries in the Levant, amount to about five millions, and they are the most active and intelligent portion of the population of the greater part of the provinces in which they dwell. The declining state of the Ottoman empire, and the warlike spirit of the Greek mountaineers and sailors, induced both Russia and England to commence bidding for the favour of the insurgents. In 1822 the deputy sent by the Greeks to solicit the compassion of the European ministers assembled at Verona, was not allowed to approach the Congress. But the successful resistance of the Greeks to the whole strength of the Ottoman empire for two years, induced Russia to communicate a memoir to the European cabinets in 1824, proposing that the Greek population then in arms should receive a separate, though independent, political existence. This indiscreet proposition awakened the jealousy of England, as indicating the immense importance attached by Russia to securing the good-will of the Greeks. England immediately outbid the Czar for their favour, by recognising the validity of their blockades of the Turkish fortresses, thus virtually acknowledging the existence of the Greek state. The other European powers were compelled most unwillingly to follow the example of Great Britain. Mr Canning, however, in order to place the question on some public footing, laid down the principles on which the British cabinet was determined to act, in a communication to the Greek government, dated in the month of December 1824. This document declares that the British government will observe the strictest neutrality with reference to the war; while with regard to the intermediate state of independence and subjection proposed in the Russian memorial, it adds that, as it has been rejected by both parties, it is needless to discuss its advantages or defects. It also assured the Greeks that Great Britain would take no part in any attempt to compel them by force to adopt a plan of pacification contrary to their wishes.

France now thought fit to enter on the field. According to the invariable principle of modern French diplomacy, she made no definite proposition either to the Greeks or the European powers; but she sent semi-official agents into the country, who made great promises to the Greeks if they would choose the Duke de Nemours, the second son of the Duke d'Orleans, now King Louis Philippe, to be sovereign of Greece. The Greeks had seen something too substantial on the part of Russia and England to follow this Gallic will-o'-the-wisp. But England and Russia, in order to brush all the cobwebs of French intrigue from a question which appeared to them too important to be dealt with any longer by unauthorized agents, signed a protocol at St Petersburg on the 4th April 1826, engaging to use their good offices with the Sultan to put an end to the war. The Duke of Wellington himself negotiated the signature of this protocol, and it is one of the numerous services he has rendered to his country and to Europe, as the Greek question threatened to disturb the peace of the East. France, as well as Austria, refused to join, until it became evident that the two powers were taking active measures to carry their decisions into effect, when France gave in her adhesion, and the treaty of the 6th of July 1827, was signed at London by France, Great Britain, and Russia.

Events soon ran away with calculations. The Turkish fleet was destroyed at Navarino on the 20th October 1827, the anniversary (if we may trust Mitford's History of Greece) of the battle of Salamis. France now embarked in the cause, determined to outbid her allies, and sent an expedition to the Morea, under Marshal Maison, to drive out the troops of Ibrahim Pasha. Capo d'Istria assumed the absolute direction of political affairs, and by his Russian partizanship and anti-Anglican prejudices, plunged Greece in a new revolution, when his personal oppression of the family of Mauromichalis caused his assassination. King Otho was then selected as king of Greece, and the consent of the Greeks was obtained to his appointment by a loan to the new monarch of £.2,400,000 sterling, and by a good deal of intrigue and intimidation at the assembly of Pronia.22 The Greeks, however, had already solemnly informed the allied powers, that the acts of their national assemblies, consolidating the institutions of the Greek state, and by securing the liberties of the Greek people, "were as precious to Greece as her existence itself;" and the protecting powers had consecrated their engagement to support these institutions, by annexing this declaration to their protocol of the 22d March 1830.23