полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 470, January 8, 1831

Notes of a Reader

KNOWLEDGE FOR THE PEOPLE; OR, THE PLAIN WHY AND BECAUSE

PART III.—Origins and AntiquitiesThis contains the Why and Because of the Curiosities of the Calendar; the Customs and Ceremonies of Special Days; and a few of the Origins and Antiquities of Social Life. We quote a page of articles, perhaps, the longest in the Number:—

Cock-fightingWhy was throwing at cocks formerly customary on Shrove Tuesday?

Because the crowing of a cock once prevented our Saxon ancestors from massacreing their conquerors, another part of our ancestors, the Danes, on the morning of a Shrove Tuesday, while asleep in their beds.

This is the account generally received, although two lines in an epigram "On a Cock at Rochester," by the witty Sir Charles Sedley, imply that the cock suffered this annual barbarity by way of punishment for St. Peter's crime, in denying his Lord and Master—

"Mayst thou be punish'd for St. Peter's crime,And on Shove Tuesday perish in thy prime."A writer in the Gentleman's Magazine also says—"The barbarous practice of throwing at a cock tied to a stake on Shrovetide, I think I have read, has an allusion to the indignities offered by the Jews to the Saviour of the World before his crucifixion."—Ellis's Notes to Brand.

Why was cock-fighting a popular sport in Greece?

Because of its origin from the Athenians, on the following occasion: When Themistocles was marching his army against the Persians, he, by the way, espying two cocks fighting, caused his army to halt, and addressed them as follows—"Behold! these do not fight for their household gods, for the monuments of their ancestors, nor for glory, nor for liberty, nor for the safety of their children, but only because the one will not give way to the other."—This so encouraged the Grecians, that they fought strenuously, and obtained the victory over the Persians; upon which, cock-fighting was, by a particular law, ordered to be annually celebrated by the Athenians.

Cæsar mentions the English cocks in his Commentaries; but the earliest notice of cock-fighting in England, is by Fitzstephen the monk, who died in 1191.

St. GeorgeWhy is St. George the patron saint of England?

Because, when Robert, Duke of Normandy, the son of William the Conqueror, was fighting against the Turks, and laying siege to the famous city of Antioch, which was expected to be relieved by the Saracens, St. George appeared with an innumerable army, coming down from the hills, all clad in white, with a red cross on his banner, to reinforce the Christians. This so terrified the infidels that they fled, and left the Christians in possession of the town.—Butler.

Why is St. George usually painted on horseback, and tilting at a dragon under his feet?

Because the representation is emblematical of his faith and fortitude, by which he conquered the devil, called the dragon in the Apocalypse.—Butler.

Why was the Order of the Garter instituted?

Because of the victory obtained over the French at the battle of Cressy, when Edward ordered his garter to be displayed as a signal of battle; to commemorate which, he made a garter the principal ornament of an order, and a symbol of the indissoluble union of the knights. The order is under the patronage or protection of St. George, whence he figures in its insignia. Such is the account of Camden, Fern, and others. The common story of the order being instituted in honour of a garter of the Countess of Salisbury, which she dropped in dancing, and which was picked up by King Edward, has been denounced as fabulous by our best antiquaries.

Cock-crowWhy was it formerly supposed that cocks crowed all Christmas-eve?

Because the weather is then usually cloudy and dark (whence "the dark days before Christmas,") and cocks, during such weather, often crow nearly all day and all night. Shakspeare alludes to this superstition in Hamlet—

Some say that even 'gainst that hallow'd season,At which our Saviour's birth is celebrated,The Bird of Dawning croweth all night long.The nights are wholesome, and no mildew falls;No planet strikes, nor spirits walk abroad:No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,So gracious and so hallowed is the time.The ancient Christians divided the night into four watches, called the evening, midnight, and two morning cock-crowings. Their connexion with the belief in walking spirits will be remembered—

The cock crows, and the morn prows on,When 'tis decreed I must be gone."—Butler.—The taleOf horrid apparition, tall and ghastly,That walks at dead of night, or takes his standO'er some new-open'd grave; and, strange to tell,Evanishes at crowing of the cock—Blair.Who can ever forget the night-watches proclaimed by the cock in that scene in Comus, where the two brothers, in search of their sister, are benighted in a forest?—

—Might we but hearThe folded flocks, penned in their wattled cotes,Or sound of pastoral reed with oaten stops,Or whistle from the lodge, or village cockCount the night-watches to his feathery dames,'Twould be some solace yet, some little cheering,In this close dungeon of innumerous boughs.Dr. Forster observes—"There is this remarkable circumstance about the crowing of cocks—they seem to keep night-watches, or to have general crowing-matches, at certain periods—as, soon after twelve, at two, and again at day-break. These are the Alectrephones mentioned by St. John. To us, these cock-crowings do not appear quite so regular in their times of occurrence, though they actually observe certain periods, when not interrupted by the changes of the weather, which generally produce a great deal of crowing. Indeed, the song of all birds is much influenced by the state of the air." Dr. F. also mentions, "that cocks began to crow during the darkness of the eclipse of the sun, Sept. 4, 1820; and it seems that crepusculum (or twilight) is the sort of light in which they crow most."

Goes of LiquorWhy did tavern-keepers originally call portions of liquor "goes?"

Because of the following incident, which, though unimportant in itself, convinces us how much custom is influenced by the most trifling occurrences:—The tavern called the Queen's Head, in Duke's-court, Bow-street, was once kept by a facetious individual of the name of Jupp. Two celebrated characters, Annesley Spay and Bob Todrington, a sporting man, meeting one evening at the above place, went to the bar, and each asked for half a quartern of spirits, with a little cold water. In the course of time, they drank four-and-twenty, when Spay said to the other, "Now we'll go."—"O no," replied he, "we'll have another, and then go."—This did not satisfy the gay fellows, and they continued drinking on till three in the morning, when both agreed to GO; so that under the idea of going, they made a long stay. Such was the origin of drinking, or calling for, goes.

Why was the celebrated cabinet council of Charles II. called the Cabal?

Because the initials of the names of the five councillors formed that word, thus—

Clifford,

Arlington,

Buckingham

Ashley,

Lauderdale.

COMPANION TO THE ALMANAC

The volume for the present year appears to bring into play all the advantages of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The majority of the papers are of permanent value,—as the Division of the Day—a Table of the difference between London and Country Time—the continuation of the "Natural History of the Weather," commenced in last year's Companion—Chronological Table of Political Treaties, from 1326—a Literary Chronology of Contemporaneous Authors from the earliest times, on the plan of last year's Regal Table—Tables for calculating the Heights of Mountains by the Barometer—and illustrative papers on Life Assurance, the Irish Poor, and East India Trade.

The condensations of the official documents of the year follow; and from these we select two or three examples:

Bankruptcy Analysis, from November 1, 1829, to November 1, 1830Agricultural Implement Maker, 1; Anchorsmiths, 3; Apothecaries, 7; Auctioneers, 10; Bakers, 15; Bankers, 3; Barge-master, 1; Basket-maker, 1; Blacksmiths, 2; Bleacher, 1; Boarding-house Keepers, 9; Boarding-school Keeper, 1; Boat-builder, 1; Bombasin Manufacturer, 1; Bone Merchant, 1; Bookbinders, 3; Booksellers, 20; Boot and Shoemakers, 14; Brassfounders, 4; Brewers, 17; Bricklayers, 5; Brickmakers, 4; Brokers, 10; Brush Manufacturer, 1; Builders, 38; Butchers, 8; Cabinet Makers, 9; Calico Printers, 3; Canvass Manufacturer, 1; Cap Manufacturer, 1; Carpenters, 12; Carpet Manufacturer, 1; Carriers, 4; Carvers and Gilders, 2; Cattle Dealers, 13; Cement Maker, 1; Cheesemongers, 12; China Dealers, 2; Chemists and Druggists, 16; Clothes' Salesman 1; Clothiers, 9; Cloth Merchants, 8; Coach Builders, 10; Coach Proprietors, 9; Coal Merchants, 28; Coffeehouse Keeper, 1; Colour Maker, 1; Commission Agents, 7; Confectioners, 3; Cook, 1; Cork Merchants, 2; Corn Merchants, 36; Cotton Manufacturers, 16; Curriers, 8; Cutlers, 3; Dairyman, 1; Dealers, 20; Drapers, 35; Drysalter, 1; Dyers, 12; Earthenware Manufacturers, 4; Edge-tool Maker, 1; Engineers, 5; Factors, 4; Farmers, 15; Farrier, 1; Feather Merchants, 3; Fellmongers, 2; Fishmongers, 2: Flannel Manufacturers, 2; Flax-dressers, &c., 2; Fruit Salesman 1; Furriers, 3; Gardener, 1; Gingham Manufacturers, 2; Glass Cutters, 2; Glass Dealers, 3; Glove Manufacturers, 2; Goldsmiths, 2; Grazier, 1; Grocers, 98; Gunmakers, 4; Haberdashers, 4; Hardwareman, 1; Hat Manufacturers, 9; Hop Merchants, 2; Horse Dealers, 10; Hosiers, 9; Innkeepers, 40; Ironfounders, 5; Iron Masters, 4; Iron Merchants, 4; Ironmongers, 19; Jewellers, 7; Joiners, 7; Lace Dealer, 1; Lace Manufacturers, 3; Lapidary 1; Leather Cutters, 2; Leather Dressers, 2; Lime Burners, 5; Linendrapers, 62; Linen Manufacturers, 2; Livery Stable Keepers, 9; Looking Glass Manufacturer, 1; Machine Makers, 2; Maltsters, 9; Manchester Warehousemen, 2; Manufacturers, 10; Manufacturing Chemist, 1; Master Mariners, 10; Mast Maker, 1; Mattress Maker, 1; Mealman, 1; Mercers, 16; Merchants, 71; Millers, 22; Milliners, 7; Miner, 1; Money Scriveners, 21; MusicSellers, 5; Nurserymen, 4; Oil and Colourman, 8; Painters, 6; Paper Hanger, 1; Paper Manufacturers, 8; Pawnbrokers, 2; Perfumers, 4; Picture Dealers, 3; Pill Box Maker, 1; Plasterer, 1; Plumbers, 12; Porter Dealers, 2; Potter, 1; Poulterer, 1; Printers, 4; Provision Brokers, 2; Ribbon Manufacturers, 6; Rope Manufacturer, 1; Sack Maker, 1; Saddlers, 6; Sail Cloth Makers, 2; Sail Makers, 4; Salesmen, 3; Scavenger, 1; Schoolmasters, 6; Seedsmen, 2; Ship Chandlers, 3; Ship Owners, 5; Shipwrights, 8; Shopkeepers, 11; Silk Manufacturers, 6; Silk Throwsters, 2; Silversmiths, 2; Slate Merchants, 2; Smiths, 2; Soap Maker, 1; Stationers, 7; Statuaries, 2; Steam Boiler Manufacturers, 2; Stock Brokers, 2; Stocking Manufacturer, 1; Stonemasons, 8; Stuff Merchants, 7; Sugar Refiner, 1; Surgeons, 13; Surveyor, 1; Tailors, 25; Tallow Chandler, 1; Tanners, 7; Tavern Keepers, 3; Timber Merchants, 18; Tinmen, 3; Tobacconists, 4; Toymen, 3; Turners, 2; Umbrella Manufacturer, 1; Underwriter, 1; Upholsterers, 16; Veneer Cutter, 1; Victuallers, 88; Warehousemen, 15; Watch and Clock Makers, 6; Wax Chandler 1; Wheelwright, 1; White Lead Manufacturer, 1; Whitesmith, 1; Whitster, 1; Wine and Spirit Merchants, 50; Woollen Drapers, 18; Woolstaplers, 5; Worsted Manufacturers, 6.—Total, 1467.

This is but a gloomy page in the commercial annals.

Duties on Soap and CandlesThe amount of the duty on Candles has been, for the year ending 5th of Jan. 1826, 491,236l.; 1827, 471,994l.; 1828, 492,622l.; 1829, 503,779l.; 1830, 495,138l.

The rate of duty on the above articles is—On hard soap, 3d. per lb.; soft soap, 1¾d.; candles, tallow, 1d. per lb.; wax and spermaceti, 3½d. These duties are payable by law one week after the accounts are made up; but as the accounts for the country include the operations of six or seven weeks alternately, the period allowed for payment depends upon the locality of the traders, as those resident where the collector attends latest upon the round have a proportionally longer credit; the time allowed for payment may be stated generally at from fourteen to twenty-eight days. Within the limits of the chief office the duties on candles are paid weekly; but those on soap have, by custom, been extended to fourteen days after the account has been made up.

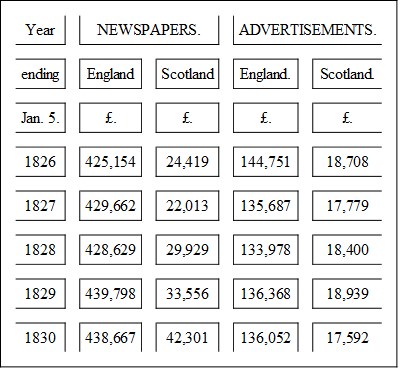

Duties on NewspapersAmount of Stamp Duties on Newspapers and Advertisements in England and Scotland, during the five years ending January 5, 1830:

In Ireland the total number of Newspaper Stamps issued has been, in the years ending 5th Jan. 1827, 3,473,014; 1828, 3,545,846; 1829, 3,790,272; and 1830, 3,953,550.

The Selector;

AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

MOORE'S LIFE OF BYRON. VOL. II

It is our intention to condense a sheet of extracts from the above volume, upon the plan adopted by us on the appearance of the previous portion of the work. Our publishing arrangements will not, however, advantageously allow the appearance of this sheet until next Saturday week. In the meantime, a few extracts, per se, may gratify the curiosity of the reader, and not interfere with the interest of our proposed Supplement.

Extracts from Lord Byron's Journal"Diodati, near Geneva, Sept. 19th, 1816.

"Rose at five. Crossed the mountains to Montbovon on horseback, and on mules, and, by dint of scrambling, on foot also; the whole route beautiful as a dream, and now to me almost as indistinct. I am so tired;—for, though healthy, I have not the strength I possessed but a few years ago. At Montbovon we breakfasted; afterwards, on a steep ascent, dismounted; tumbled down; cut a finger open; the baggage also got loose and fell down a ravine, till stopped by a large tree; recovered baggage; horse tired and drooping; mounted mule. At the approach of the summit of Dent Jument1 dismounted again with Hobhouse and all the party. Arrived at a lake in the very bosom of the mountains; left our quadrupeds with a shepherd, and ascended farther; came to some snow in patches, upon which my forehead's perspiration fell like rain, making the same dints as in a sieve; the chill of the wind and the snow turned me giddy, but I scrambled on and upwards. Hobhouse went to the highest pinnacle; I did not, but paused within a few yards (at an opening of the cliff.) In coming down, the guide tumbled three times; I fell a laughing, and tumbled too—the descent luckily soft, though steep and slippery; Hobhouse also fell, but nobody hurt. The whole of the mountains superb. A shepherd on a very steep and high cliff playing upon his pipe; very different from Arcadia, where I saw the pastors with a long musket instead of a crook, and pistols in their girdles. Our Swiss shepherd's pipe was sweet, and his tune agreeable. I saw a cow strayed; am told that they often break their necks on and over the crags. Descended to Montbovon; pretty scraggy village, with a wild river and a wooden bridge. Hobhouse went to fish—caught one. Our carriage not come; our horses, mules, &c. knocked up; ourselves fatigued.

"The view from the highest points of to-day's journey comprised on one side the greatest part of Lake Leman; on the other, the valleys and mountain of the Canton of Fribourg, and an immense plain, with the Lakes of Neuchâtel and Morat, and all which the borders of the Lake of Geneva inherit; we had both sides of the Jura before us in one point of view, with Alps in plenty. In passing a ravine, the guide recommended strenuously a quickening of pace, as the stones fall with great rapidity and occasional damage; the advice is excellent, but, like most good advice, impracticable, the road being so rough that neither mules, nor mankind, nor horses, can make any violent progress. Passed without fractures or menace thereof.

"The music of the cows' bells (for their wealth, like the patriarchs', is cattle,) in the pastures, which reach to a height far above any mountains in Britain, and the shepherds shouting to us from crag to crag, and playing on their reeds where the steeps appeared almost inaccessible, with the surrounding scenery, realized all that I have ever heard or imagined of a pastoral existence;—much more so than Greece or Asia Minor, for there we are a little too much of the sabre and musket order—and if there is a crook in one hand, you are sure to see a gun in the other;—but this was pure and unmixed—solitary, savage, and patriarchal. As we went, they played the 'Ranz des Vaches' and other airs by way of farewell. I have lately repeopled my mind with nature.

"Sept. 20th."Up at six; off at eight. The whole of this day's journey at an average of between from 2,700 to 3,000 feet above the level of the sea. This valley, the longest, narrowest, and considered the finest of the Alps, little traversed by travellers. Saw the bridge of La Roche. The bed of the river very low and deep, between immense rocks, and rapid as anger;—a man and mule said to have tumbled over without damage. The people looked free, and happy, and rich (which last implies neither of the former;) the cows superb; a bull nearly leapt into the char-à-banc—'agreeable companion in a post-chaise;' goats and sheep very thriving. A mountain with enormous glaciers to the right—the Klitzgerberg; further on, the Hockthorn—nice names—so soft;—Stockhorn, I believe, very lofty and scraggy, patched with snow only; no glaciers on it, but some good epaulettes of clouds.

"Passed the boundaries, out of Vaud and into Berne canton; French exchanged for bad German; the district famous for cheese, liberty, property, and no taxes. Hobhouse went to fish—caught none. Strolled to the river—saw boy and kid—kid followed him like a dog—kid could not get over a fence, and bleated piteously—tried myself to help kid, but nearly overset both self and kid into the river. Arrived here about six in the evening. Nine o'clock—going to bed; not tired to-day, but hope to sleep, nevertheless."

"Sept. 22nd."Left Thoun in a boat, which carried us the length of the lake in three hours. The lake small, but the banks fine. Rocks down to the water's edge. Landed at Newhause—passed Interlachen—entered upon a range of scenes beyond all description, or previous conception. Passed a rock: inscription—two brothers—one murdered the other; just the place for it. After a variety of windings came to an enormous rock. Arrived at the foot of the mountain (the Jungfrau, that is, the Maiden)—glaciers—torrents: one of these torrents nine hundred feet in height of visible descent. Lodged at the curate's. Set out to see the valley—heard an avalanche fall, like thunder—glaciers enormous—storm came on, thunder, lightning, hail—all in perfection, and beautiful. I was on horseback; guide wanted to carry my cane; I was going to give it him, when I recollected that it was a sword-stick, and I thought the lightning might be attracted towards him; kept it myself; a good deal encumbered with it, as it was too heavy for a whip, and the horse was stupid, and stood with every other peal. Got in, not very wet, the cloak being stanch. Hobhouse wet through; Hobhouse took refuge in cottage; sent man, umbrella, and cloak, (from the curate's when I arrived) after him. Swiss curate's house very good indeed—much better than most English vicarages. It is immediately opposite the torrent I spoke of. The torrent is in shape curving over the rock, like the tail of a white horse streaming in the wind, such as it might be conceived would be that of the 'pale horse' on which Death is mounted in the Apocalypse.2 It is neither mist nor water, but a something between both; its immense height (nine hundred feet) gives it a wave or curve, a spreading here, or condensation there, wonderful and indescribable. I think, upon the whole, that this day has been better than any of this present excursion.

"Sept. 23rd."Before ascending the mountain, went to the torrent (seven in the morning) again; the sun upon it, forming a rainbow of the lower part of all colours, but principally purple and gold; the bow moving as you move; I never saw anything like this: it is only in the sunshine. Ascended the Wengen mountain; at noon reached a valley on the summit; left the horses, took off my coat, and went to the summit, seven thousand feet (English feet) above the level of the sea, and about five thousand above the valley we left in the morning. On one side, our view comprised the Jungfrau, with all her glaciers; then the Dent d'Argent, shining like truth; then the Little Giant (the Kleine Eigher;) and the Great Giant (the Grosse Eigher,) and last, not least, the Wetterhorn. The height of the Jungfrau is 13,000 feet above the sea, 11,000 above the valley: she is the highest of this range. Heard the avalanches falling every five minutes nearly. From whence we stood, on the Wengen Alp, we had all these in view on one side; on the other, the clouds rose from the opposite valley, curling up perpendicular precipices like the foam of the ocean of hell, during a spring tide—it was white and sulphury, and immeasurably deep in appearance.3 The side we ascended was, of course, not of so precipitous a nature; but on arriving at the summit, we looked down upon the other side upon a boiling sea of cloud, dashing against the crags on which we stood (these crags on one side quite perpendicular.) Staid a quarter of an hour—begun to descend—quite clear from cloud on that side of the mountain. In passing the masses of snow, I made a snowball and pelted Hobhouse with it.

"Got down to our horses again; ate something; remounted; heard the avalanches still: came to a morass; Hobhouse dismounted to get over well; I tried to pass my horse over; the horse sunk up to the chin, and of course he and I were in the mud together; bemired, but not hurt; laughed, and rode on. Arrived at the Grindenwald; dined, mounted again, and rode to the higher glacier—like a frozen hurricane.4 Starlight, beautiful, but a devil of a path! Never mind, got safe in; a little lightning, but the whole of the day as fine in point of weather as the day on which Paradise was made. Passed whole woods of withered pines, all withered; trunks stripped and lifeless, branches lifeless; done by a single winter."5

Shelley and Byron,It appears, first met at Geneva:—

There was no want of disposition towards acquaintance on either side, and an intimacy almost immediately sprung up between them. Among the tastes common to both, that for boating was not the least strong; and in this beautiful region they had more than ordinary temptations to indulge in it. Every evening, during their residence under the same roof at Sécheron, they embarked, accompanied by the ladies and Polidori, on the Lake; and to the feelings and fancies inspired by these excursions, which were not unfrequently prolonged into the hour of moonlight, we are indebted for some of those enchanting stanzas6 in which the poet has given way to his passionate love of Nature so fervidly.

"There breathes a living fragrance from the shoreOf flowers yet fresh with childhood; on the earDrips the light drop of the suspended oar.At intervals, some bird from out the brakesStarts into voice a moment, then is stillThere seems a floating whisper on the hill,But that is fancy,—for the starlight dewsAll silently their tears of love instil,Weeping themselves away."A person who was of these parties has thus described to me one of their evenings. 'When the bise or northeast wind blows, the waters of the Lake are driven towards the town, and, with the stream of the Rhone, which sets strongly in the same direction, combine to make a very rapid current towards the harbour. Carelessly, one evening, we had yielded to its course, till we found ourselves almost driven on the piles; and it required all our rowers' strength to master the tide. The waves were high and inspiriting,—we were all animated by our contest with the elements. 'I will sing you an Albanian song,' cried Lord Byron; 'now be sentimental, and give me all your attention.' It was a strange, wild howl that he gave forth; but such as, he declared, was an exact imitation of the savage Albanian mode, laughing, the while, at our disappointment, who had expected a wild Eastern melody.